What is the difference between pharmaceuticals and food supplements? This may not be a question raised all that often by the average person, but it can be very important when considering trade mark protection in the healthcare space. This question was considered in a recent trade mark case involving two companies operating in the healthcare sector.

NATURCAPS vs NATURKAPS

Esi s.r.l., an Italian company focused on the production and sale of natural remedies, applied to register the mark NATURCAPS in the EU in relation to, among other goods, 'dietary and nutritional supplements' in Class 5. Following the registration of the mark, the Polish company, Hasco TM sp. Z o.o. sp.k, sought to invalidate Esi's registration on the basis of the existence of their Polish national trade mark registration for the mark NATURKAPS, which was registered for 'pharmaceutical products', also in Class 5.

In the cancellation proceedings, Esi requested that Hasco file evidence that it had been using its mark for the goods for which it was registered. Hasco filed its proof of use evidence and presumably assumed this would be sufficient to demonstrate that its NATURKAPS mark had been used in relation to pharmaceutical products. However, the evidence Hasco filed predominantly showed use of its mark in relation to goods considered to be food supplements, and these goods were held not to be similar enough to pharmaceutical products to allow for the evidence to be sufficient to show use of the mark for the registered goods. As a result, the cancellation action fell away.

Hasco appealed the decision and sought to demonstrate that food supplements were, in fact, similar enough to pharmaceutical products so as to allow the evidence as proof it has used its mark. The first appeal was unsuccessful and Hasco pursued the matter to the General Court of the European Union. In the proceedings, Hasco's argued that there was no real differentiation between pharmaceuticals and food supplements and that both shared the same trade channels and had the same intended purpose, that is to improve the end user's health. Therefore, use of the mark on food supplements must necessarily be covered under the broad term "pharmaceutical products" contained in the registration. The term "pharmaceutical products" is in essence a generic term including both medicinal products as well as food supplements. This argument was not enough to convince the General Court, which stated that Hasco had the opportunity to include the term 'dietetic substances adapted for medical use' at the time of filing, which would have helped cover the food supplement goods which were being sold under the mark. Also, the fact that pharmaceutical products and food supplements can be sold in the same shops does not lead to a finding that the goods themselves are similar, and that use in relation to one type of good can be used as evidence of use on the other. Following this, the further appeal was dismissed.

Trade Mark Protection – Food Supplements or Pharmaceuticals?

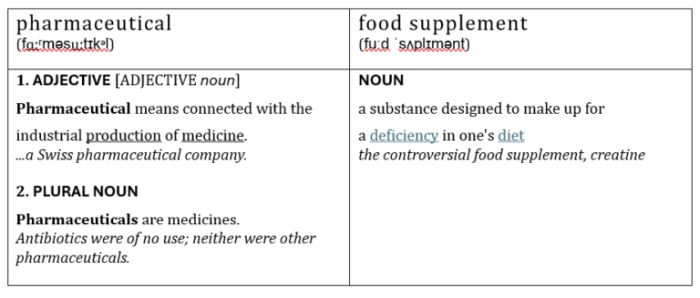

According to the Collins Dictionary, the definitions of "Food Supplements" and "Pharmaceuticals" are as follows:

As you can see, the words are defined quite narrowly, but could be considered to overlap, especially if a person's dietary deficiencies were causing them medical problems that had to be addressed by the administering of, well... pharmaceuticals... or should that be food supplements?

These ambiguities can start to be addressed when considering the scenario in the context of trade mark law as laid out in the above NATURKAPS case.

Trade marks play a critical role in distinguishing products in the market, providing legal protection and ensuring brand recognition. Part of the framework of trade mark practice is the grouping of goods and services for which the mark will cover into 'classes'. This classification system is an administrative tool that allows trade mark owners to identify other rights that may overlap with their own whilst concisely stating in which areas of commerce they are claiming rights. Food supplements and pharmaceuticals both fall under Class 5 of this classification system. However, despite the fact they fall into the same class, the nature of their intended use, trade channels and type of consumer can differ significantly. This was highlighted in the NATURKAPS case, but in order to help explain this further, let's take a look at the regulatory environment in which food supplements and pharmaceuticals operate.

Pharmaceuticals:

These products are subject to rigorous regulatory scrutiny due to their direct impact on human health. Regulatory bodies such as the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency in the UK, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) all require extensive testing and drug trial processes in order for a pharmaceutical to be approved for sale on the open market. Consequently, trade marks for pharmaceuticals often undergo stringent examination to prevent misleading claims that could affect public health. This includes a stricter process of scrutiny in relation to the similarity of marks, so as to ensure there is as little chance as possible of confusion. This is to avoid a consumer purchasing a product which could be detrimental to their health because it has a similar name.

Food Supplements:

In the UK, food supplements are required to be regulated as foods and are subject to the provisions of general food law which is based on the principle that products must be safe for consumption and not misleadingly labelled. Food law does not permit any food to make any claim, or imply that it can treat, prevent or cure any disease or adverse medical condition. While also being regulated, this is done so by the UK Nutrition and Health Claims Committee (UKNHCC) and the guidelines leading to the successful approval of a food supplement are less ridged compared to those governing pharmaceuticals.

These differences affect the examination of trade marks. For pharmaceuticals, the requirement for distinctiveness in trade marks is critical. As touched on above, the names must be unique to avoid confusion with existing drugs, which can lead to serious health risks. Therefore, the trade mark examination process involves close consideration of any potentially descriptive elements of the mark, and the examiner will very likely refuse to register any mark containing a descriptive element. For food supplements, while distinctiveness is important, the threshold is generally lower compared to pharmaceuticals and the emphasis is more on avoiding confusion within the supplement market rather than across all medicinal products.

Pharmaceuticals are often prescription-based and are usually recommended and administered by healthcare professionals. Thus, trade marks need to be easily distinguishable and pronounceable to ensure accurate identification by both the doctor, nurse or pharmacist who may be obtaining them, as well as by the average consumer who may be purchasing them over the counter.

In contrast, food supplements are usually exclusively sold via food or health stores either on the high street or online, and are purchased by the average consumer. The trademarks here focus more on marketing appeal and brand recognition to attract consumers directly rather than seeking to avoid confusion with existing medicines that are already available.

The assessment of this potential confusion also feeds into an important point when it comes to differentiating pharmaceuticals and food supplements, in that how a company uses a mark can determine how enforceable third mark is in the healthcare space.

Conclusion

As we can now see, obtaining trade mark protection for food supplements or pharmaceuticals involves considering different regulatory environments, distinctiveness requirements, and public perceptions. While both food supplements and pharmaceuticals fall under the same class, the level of scrutiny and the nature of trade mark examination differ due to their respective impacts on public health and market dynamics.

The NATURCAPS v NATURKAPS case highlights the importance of ensuring clear distinctions in relation to the use of a marks to avoid confusion and maintain market integrity.

As the market for health-related products continues to grow, understanding these nuances becomes increasingly important for businesses seeking to protect and promote their brands effectively.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.