The U.S. international tax regime is fraught with traps for the unwary for non-U.S. persons doing (or thinking of doing) business in the United States. Complicated rules affect whether non-U.S. persons are subject to tax on their U.S.-sourced income as well as U.S. shareholders holding minority interests in inbound structures.

In this alert, which is the first in a series on tax issues regarding inbound investments, we address:

- Controlled foreign corporations ("CFCs") hidden in plain sight, and

- Recent rules impacting foreign investment in U.S. real property.

CFCs Hidden in Plain Sight

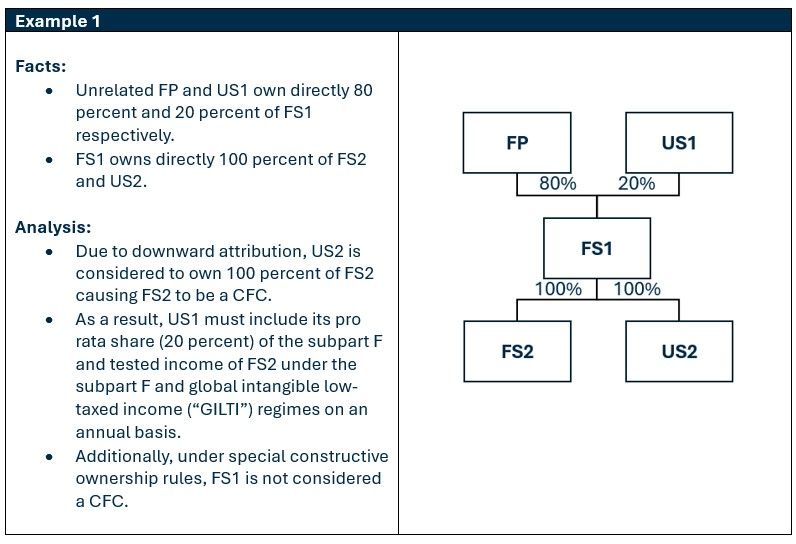

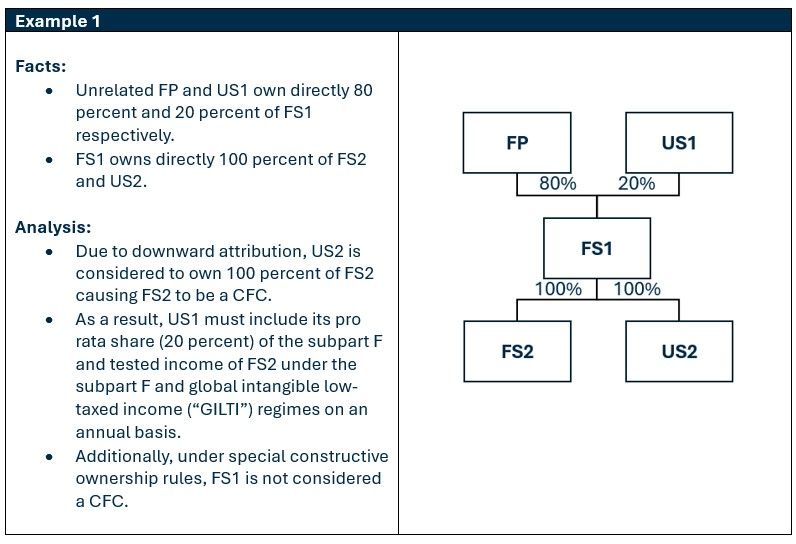

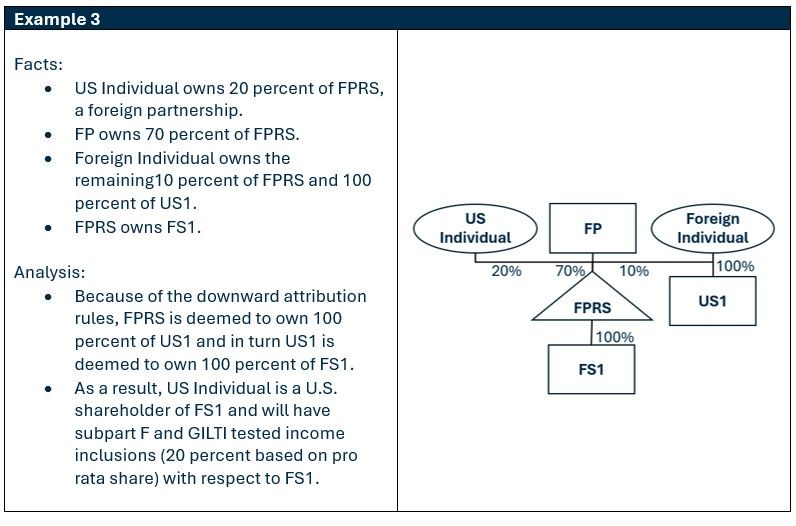

The U.S. has a faux-territorial system of taxing U.S. persons. One component of this system is its CFC regime under which direct and indirect U.S. shareholders of a CFC are subject to tax on most income of that CFC. A CFC is any foreign corporation with more than 50 percent of its stock, by vote or value, owned by U.S. shareholders. A U.S. shareholder is any U.S. person who owns at least 10 percent, by vote or value, of the foreign corporation directly, indirectly, or constructively through ownership attribution rules. While all U.S. shareholders are considered when determining whether a foreign corporation is a CFC, only direct and indirect (and not constructive) shareholders have U.S. income inclusions.

The TCJA significantly expanded the constructive ownership rules for the purposes of determining whether a foreign corporation is a CFC by permitting downward attribution of share ownership to partnerships, estates, trusts, and other corporations when testing whether a foreign corporation is a CFC.

The examples below illustrating the effect of downward attribution involve foreign corporations (FP and FS entities) and U.S. corporations (US1 and US2).

A&M Insight

A comprehensive understanding of the entire organizational structure (including entities owned by shareholders), coupled with strategic tax planning, can pinpoint and often mitigate the risk of a foreign corporation being classified as a CFC. This is crucial to prevent unintended income inclusions for any direct or indirect U.S. shareholders. It is particularly critical in scenarios akin to Example 2, where proactive planning is essential prior to the involvement of any U.S. shareholders in the structure.

Recent Rules Impacting Foreign Investment in U.S. Real Property

The Foreign Investment in Real Property Tax Act ("FIRPTA") imposes a U.S. tax on foreign person's disposition of U.S. real property interests ("USRPIs"). A USPRI is broadly defined and includes a wide range of real property interests in the U.S. and the Virgin Islands, including interests held in a U.S. real property holding company ("USRPHC"). Any U.S. corporation could be classified as a USPHC unless it can prove that it has not held a majority of its assets in USPRIs in the past five years.

However, FIRPTA provides an exemption for gains on the sale or exchange of interests in qualified investment entities ("QIEs"), such as domestically controlled real estate investment trusts ("REITs") and certain regulated investment companies ("RICs"). It is important to note that this exemption applies only to the dispositions of the QIE's stock, and not to capital gain dividends or distributions of USRPIs by the QIEs.

Generally, a QIE is domestically controlled if less than 50 percent of the value of the stock is directly or indirectly held by foreign persons at all times during the relevant testing period, which is generally the five-year period preceding the disposition. The U.S. Treasury issued final regulations in April 2024 that offer detail guidance on determining whether a QIE is domestically controlled. These regulations introduce the concepts of "look-through persons" and "non-look-through persons" to ascertain indirect stock ownership in a QIE. To determine a QIE's domestic control status, one must "look-through" each look-through entity until a non-look through entity is reached.

The regulations define a look-through person as any person other than a non-look-through person. A non-look-through person is:

- An individual,

- A domestic C corporation that is not a foreign-controlled domestic corporation,

- A non-taxable holder,

- A foreign corporation, including a foreign government,

- A publicly traded partnership,

- A publicly traded RIC,

- An estate,

- An international organization,

- A qualified foreign pension fund ("QFPF"), and

- Any qualified controlled entity of a QFPF.

In addition, the rules impose an actual knowledge test upon the QIE. First, any shareholder owning less than 5 percent of the QIE is treated as a U.S. non-look-through person unless the QIE has actual knowledge that the person is a non-U.S. person. Further, no shareholder is treated as a non-look-through person if the QIE has actual knowledge that the person is foreign-controlled.

The regulations provide transition rules that may alleviate the impact of the rules on existing structures by generally exempting preexisting domestically controlled QIE structures from the domestic corporation look-through rule for a 10-year period. However, the exemption is lost when either of the following two events occur:

- Significant acquisitions of USRPIs – The QIE acquires additional USRPIs after April 24, 2024, and the additional properties have a fair market value that is more than 20 percent of the fair market value of the USPRIs held by the QIE as of April 24, 2024; and

- Significant ownership changes – The ownership of the QIE by non-look-through persons increases by more than 50 percentage points in the aggregate over the amount owned on April 24, 2024.

If either of the above thresholds are exceeded, the QIE would become subject to the domestic corporation look-through rule at that time and may lose its domestically controlled status.

A&M Insight

Careful review and monitoring of the strict transition rules is critical because triggering one of the conditions could result in the foreign persons being subject to U.S. tax on any disposition of an interest in the QIE. As a result, the potential implications of these rules should be considered in the analysis of any transactions involving QIEs. Further, foreign entities that have undertaken domestically controlled QIE analysis prior to the issuance of the final rules should reevaluate their structures to determine whether the transition rule applies and whether any additional analysis and planning is needed. In addition, foreign persons that own a QIE on April 24, 2024, that qualified as a domestically controlled QIE before the issuance of the regulations, may want to sell their interest before April 24, 2034, when the transition rule sunsets.

A&M Tax Says

The tax rules impacting investment in the U.S. by foreign persons are complex and littered with traps for the unwary. Foreign persons should be wary when structuring their investment in the U.S. to ensure their structure not only meets their business objectives but also is tax efficient from a U.S. (and non-U.S.) perspective. Failure to properly account for any foot-faults can have significant ramifications that in certain instances can be costly to cure retroactively if they can be cured at all.

Originally Published 23 May 2024

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.