The United States occupies a leadership position in clinical advancements, in terms of pharmaceuticals, medical devices, innovative care processes and interventional techniques. At the nexus of these advances are clinical trials. Trials are conducted in many types of clinical settings, but academic medical centers (AMCs), with their close ties to bench research and the analytic infrastructure and expertise inherent in their organizations, are central to the process, particularly as they evolve into multi-site and geographically distributed health systems.

Participation in clinical trials in the United States (U.S.) however, is generally low, which impacts the rate at which new treatments can be introduced into clinical settings; as many as 20% of clinical trials are terminated early for failing to meet recruitment targets or completed despite failing to meet the original target.1 Further, many trials that accrue a sufficient number of participants suffer from a lack of diversity, which includes race and ethnicity, sex with less participation by women2 and the inclusion of older adults.3 In 2020, the clinical trials supporting applications for Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of new drugs and biologics included only 8% Black or African American, 6% Asian and 11% Hispanic or Latino participants.4

The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the long-recognized problem of participation by minority populations in clinical trials, which is exacerbated by the underlying structural inequities in healthcare.5 Enrolling diverse patients in clinical trials is considerably more difficult given that these individuals often lack a regular source of care or timely access to care, and they are often diagnosed later in the course of an illness, which can compromise their eligibility for a trial. Once identified as potential research candidates, members of diverse populations have less familiarity with, and trust of, the delivery system, introducing uncertainty as to whether they will enroll in a trial or remain engaged and compliant with clinical trial requirements. Even when the familiarity and trust exists, additional barriers such as transportation, child care or language and literacy can make successful completion of a trial especially challenging.

In response, Congressional representatives and the Biden Administration enacted and introduced important new measures (see Appendix) to improve access to clinical trials for minority populations. Still, much more progress is needed, and indeed, many healthcare providers, research institutes and the pharmaceutical industry have recognized the need to redouble efforts to reach and recruit diverse populations to more clinical trials.

The Role of AMCs in Clinical Trials

AMCs continue in their central role of offering clinical trials, and they are expanding their efforts to reach diverse populations. Strategies to improve diversity in clinical trials must advance ways to build trust and engagement with diverse populations, a complex and long-term undertaking that is more challenging for some AMCs because their campus-centricity can lead to their being less connected to their communities. However, as AMCs have become health systems with more locations in the community, the opportunities to reach more patients for expanded clinical trial accrual has also increased.

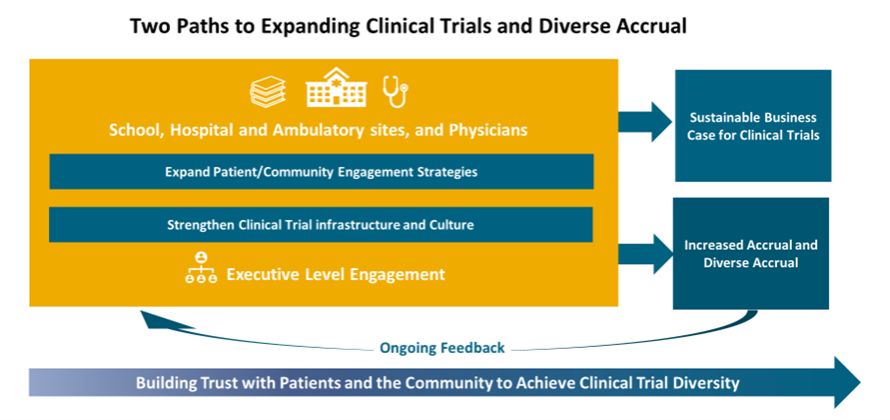

As noted in the figure below, increasing research diversity depends on closer engagement with diverse populations in the community, but equally necessary are an efficient research infrastructure and a clinical practice culture that will increase the capacity of the healthcare delivery system such that more trials are offered at the point of care. For sustainability, these programs must be organized and managed to support a business case for the organization.

We will discuss community engagement, and there is much published on strategies to address,6 but here we want to focus on the research infrastructure and the clinical practice culture and challenges specific to AMCs. Clinical trials occur at the intersection of the three principal missions of an AMC—teaching, research and patient care. They involve researchers and clinical practitioners and require an enormous amount of coordination and shared resources. The interdependence between the academic and clinical missions is critical; each contributes to the differentiation of the other. It is virtually impossible to achieve excellence in either research or clinical care without also being excellent in the other and without the inclusion of under-represented populations. This means that a strong clinical trials program that serves all in their community needs enterprise-wide support.

Given the financial pressures on the clinical operations of hospitals and AMCs, and reduced or flat budgets for federally-sponsored research, it is not infrequent that there is misalignment in funding and priorities across the AMC enterprise and within the clinical departments that undermine the organizational and resource support needed for a high-performing clinical trials program that effectively enrolls patients and diverse populations. The inability to efficiently open studies and enroll patients leads to frustration for clinician scientists, undermines translational research and can thwart research achievements, leads to the disengagement of pharma companies who are less inclined to offer novel trials when there is an inefficient operation, and it ultimately limits access to trials for patients.

High-performing clinical trial operations

A high-performing clinical trial operation opens studies efficiently, ideally in under 90 days, reaches accrual targets including diverse accrual, achieves its academic goals for research with a robust portfolio that advances translational research and meets the needs of the population served and optimizes financial performance. The organization has a clinical culture that supports physician engagement in trials and sufficient research staff to manage patients on trials. As noted above, for AMCs, the functions involved to support a trials program are often in different entities (e.g. medical school, hospital, physician group), there is wide variation in the programs across clinical departments and divisions and support is needed from departments such as information technology, human resources, finance, compliance and legal. Thus, improvement initiatives must span the enterprise and have executive-level support.

In our work with AMCs, the challenges that we often find are:

- long delays in processes to activate a clinical trial especially for Industry trials;

- Institutional Review Board (IRB) bottlenecks;

- slow turnaround time for contracting and, at times, insufficient flexibility on terms;

- research staff turnover at many levels as compensation is not competitive, and there is a limited career ladder;

- physician challenges in balancing productivity targets with the additional time required to enroll and manage a patient on a trial;

- limited education for research staff and physicians on clinical trial-related topics;

- varied expertise and level of staff across departments/divisions for the budgeting and financial management of clinical trials;

- efforts to increase diverse accrual fall to the physician investigator or their department/division with limited to no funding to support, and there is no alignment with organizational community engagement strategies for including diverse accrual to clinical trials in their planning.

Increasing Diverse Accrual

Increasing the participation of traditionally under-represented populations requires an organizational commitment to programs that build trust with patients and the community. Relationships with community organizations and providers (both medical and social services) have often not been adequately developed such that each party brings value and receives benefits. It is important to have physician investigators from diverse backgrounds, which requires mentoring and support from the organization and from the clinical department, and research staff should also reflect the diversity of the population with all staff receiving culturally-specific education for staff on barriers to research participation.

These efforts must complement rather than complicate the broader AMC outreach activities already underway. Effective strategies have many components with some noted7, but reducing barriers to timely access to care is paramount. Offering decentralized clinical trials and programs to address social determinants of health issues also eases the burden of patient participation in trials. Such an extension into the community with this research goal relies on an enterprise-wide commitment supported by executive leadership and involving multidisciplinary stakeholders.

Community Hospital Partnerships and Clinical Trial Networks

Exposure to larger patient populations through regional research affiliations and efficient accruals of broadly inclusive patient populations via trusted community partnerships will position AMCs to build on their core advantages as leading research institutions. AMCs often pursue strategies to extend their own clinical trials to the broader community through relationships with community hospitals that are within their health systems or that are affiliated. Trials with sponsorship originating outside of an AMC, including pharmaceutical or medical device investigations, place a premium on breadth of patient population from these networks and processes that can speed accruals.

Many of these AMC/Community hospital trial networks, however, underperform because there are not clear and agreed upon expectations by both parties with benefits to each, and the fact that the clinical faculty of an AMC is inherently aligned both culturally and organizationally with the research mission, which is not the case in community hospitals. The AMC often underestimates the planning and the processes that have to be addressed, the work with its clinical departments and faculty and with its research administration and other departments (e.g. IT, legal) to ensure there is support for the relationship. The community hospital in turn often is not familiar with the scope of the functions and support needed to support a clinical trials program. As AMCs pursue strategies to export clinical trials to the community, they must ensure that there is comprehensive planning to address issues before starting a relationship such as:

- To what extent are executive-level leadership engaged?

- What is the research vision, and what are the clinical areas of focus?

- Is the relationship to be a partnership to strengthen clinical trials, or will the AMC run the trials at the community hospital?

- If the hospital has an existing clinical trials program, what is the goal of the AMC clinical trial relationship (e.g. to offer more novel trials to strengthen the trial offerings)?

- Are there physician champions at the AMC and the community hospital?

- To what extent does the physician compensation program at the community hospital recognize the value of participation in clinical trials?

- What is the current state and level of efficiency of the clinical trials infrastructure at the AMC (i.e., If processes at the AMC are not efficient, the relationship will be less successful)?

- What is the current state of the infrastructure at the community hospital to support research? Are they willing to make the needed investments?

- What is the process for addressing issues related to IRB, budgeting and research rates, contracting, regulatory oversight, data sharing, etc.?

- What is the process for selecting trials for the community and assessing feasibility?

- What is the structure for overseeing the relationship?

- What are the success metrics to show benefit to each organization? What are the financial parameters that are acceptable to each organization?

Proposed Actions for AMCs to achieve a high-performing clinical trial operation

To achieve a high performing, diverse clinical trials program, the following actions are recommended:

- Assess current clinical trial activity and the supporting infrastructure across the organization, including community-based locations, to compare to high-performing organizations (see Table 1 in the Appendix, which lists assessment categories and questions);

- Prioritize the therapeutic areas for expansion of trials and assess the clinical practice and academic culture to determine what is needed to strengthen (e.g. physician recruitment to bring clinical trial expertise or to increase clinic coverage so active trialists can spend more time on research, a program to recognize physician time to participate in clinical trials);

- Identify physician champions who will advocate for efforts to identify and enroll under‑represented patient populations and engage the department that is responsible for community engagement and discuss ways to incorporate activities that will promote clinical trial participation in these populations;

- Review the financial performance and financial management of your clinical trials program to identify opportunities for improvement;

- Develop an enterprise-wide business and operational strategy for expansion of clinical trials;

- Assess the potential for any community hospital relationships, within the AMC system or affiliates, for introducing or expanding a clinical trials outreach program

Conclusion

The disparities in access to care and the inequities in health outcomes and well-being that are attracting increased national attention are mirrored in the under-representation by diverse populations in clinical trials. As leaders in research, AMCs have an imperative to expand their clinical trial accrual of these populations, but they also have the ability to grow their clinical trial programs overall with a more efficient infrastructure and a clinical practice culture that provides support for offering more trials at the point of care. This requires an enterprise-wide strategic, business and operational plan for its clinical trials program that will have executive-level engagement and some investment. Pursuing the two paths of strengthening community and patient engagement and creating a high-performing and efficient clinical trials program will enable AMCs to be more effective in advancing their critical three-part missions and in bringing scientific advances to all in their community.

Table 1: Some Questions to Assess Clinical Trial Program Performance

| Leadership and Organizational Support |

|---|

| What are your organizational-level goals for clinical trials, and how well articulated and specific are they? |

| Is there an enterprise-wide strategy and business plan for clinical trials? |

| At what level of organizational leadership is clinical trial performance and the efficiency of the clinical trial infrastructure reviewed? |

| To what extent does organizational leadership track the perception of clinical trial sponsors (e.g. industry) about the ease and efficiency of working with your clinical trials office and the culture of research in the clinical setting to support accrual of patients? |

| For health systems, is there a plan for offering clinical trials across the system, including community-based locations? If so, how effective is the program for making access to clinical trials available to patients in all locations? |

| For academic medical centers with clinical trial relationships with community hospitals, how is this initiative managed, and how effective has it been in exporting trials to the community? To what extent is this adding value for the community locations? |

| Clinical Practice Culture and Trial Performance |

| Which clinical departments are the higher/lower performers for clinical trials? |

| What percent of the faculty in each of your departments/divisions are engaged in clinical trials? To what extent does your organization promote and support the engagement of diverse investigators in the clinical trials program? |

| To what extent does the clinical practice culture and physician compensation model support faculty participation in trials? |

| What is the level of trial activity (open studies, accrual/diverse accrual by trial) in each clinical department/division? |

| What is the desired trial portfolio by department/division (e.g. sponsor, type, phase) and the processes for portfolio development? What is the process for reviewing the portfolio mix to the goals? |

| For investigator-initiated trials, to what extent is the percent of those that resulted in publications tracked? |

| Research Administrative Services and IRB |

| What is the organization's research infrastructure staffing and expertise? Where are staff members based (e.g., medical school research administration, university level, clinical practice, etc.)? What is the level of staff turnover? |

| What is the level of efficiency of the clinical trial operation (days to activate trials) by function (budgeting, coverage analysis, contracting, study start-up, etc.)? |

| What processes are used to match patients to trials (e.g. technology solutions)? How effective are they in reducing physician and staff time? |

| How efficient are the financial processes to support trials (e.g., invoicing, receivables management)? |

| What is the level of stakeholder satisfaction (e.g., physician investigators) with the research administrative functions? What are the reporting structures or processes for oversight of performance and getting stakeholder feedback? |

| Community Outreach and Patient Engagement for Accrual of Diverse Populations and Older Adults |

| How does your organization engage with its community (approach, initiatives, staffing)? Does your staff reflect the diverse make up of your community? |

| To what extent are evidence-based community outreach and engagement strategies used? To what extent are culturally-tailored strategies used to address barriers to participation in clinical trials? |

| To what extent are there formal community partnerships with organizations serving diverse populations? To what extent are they organized as bi-directional partnerships? |

| To what extent does your organization build relationships with community physicians of diverse backgrounds? |

| To what extent are there clear goals and assessment processes for the community partnerships? |

| Financial Performance |

| What are the organization's financial goals for clinical trials? |

| To what extent are trial budgets developed to adequately cover costs? Is there variation in how well this is done by department/division? |

| How, and by whom, is the financial performance for your portfolio managed and reviewed? To what extent are the financial goals achieved for your portfolio (mix of NIH, Industry and IITs)? |

| How are invoicing and accounts receivables for clinical trials managed? Is this process centralized or decentralized? How do your clinical trial receivables for your portfolio compare to benchmarks? |

APPENDIX

In recent years, Congress has passed federal legislation aimed at improving access to clinical trials, including for historically marginalized people.

- The Henrietta Lacks Enhancing Cancer Research Act (P.L. 116-291), became law on January 5, 2021. It requires the Government Accountability Office to complete a study reviewing how federal agencies address barriers to participation in federally-funded cancer clinical trials by individuals from under‑represented populations. The Act also provides recommendations for addressing such barriers.8

- The Clinical Treatment Act, ratified in December 2020 as part of the year-end funding package and effective as of Jan. 1, 2022, requires Medicaid to cover "routine costs" associated with clinical trial participation in order to help reach under‑represented populations. While there is variation by state on insurance mandates, Medicare and many private payers have covered routine costs that accompany clinical trial participation, such as fees associated with physician visits, hospital stays, diagnostic tests and other standard clinical services that would have been covered absent the patient's participation in a trial. Medicaid, however, has provided coverage on a spotty, state-by-state basis.9

- As part of the end-of-year spending package in 2022, Congress enacted FDA-related reforms that included a provision requiring drug and device sponsors to submit "diversity action plans." These plans are for the purpose of articulating goals to enroll historically under‑represented patient populations in the clinical trials supporting their applications. The provision embraced the approach previously set forth in an April 2022 draft guidance issued by FDA.10

Beyond these legislative reforms, numerous efforts to increase clinical trial diversity have been initiated within federal agencies in recent years, including:

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

- FDA issued draft guidance in April 2022 on "Diversity Plans to Improve Enrollment of Participants From Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Populations in Clinical Trials" and continues to focus on strategies to boost enrollment of diverse populations in clinical trials. FDA also will update the April 2022 guidance to align it with the recently enacted legislative changes described above.

- FDA's Oncology Center of Excellence launched its Project Equity to increase representation of diverse populations in clinical trials.11 At various points throughout the pandemic, FDA also issued guidance on the conduct of clinical trials during the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency, which provided advice on utilizing remote, or decentralized, clinical trials to permit the safe continuation of such trials.12

- In May 2023, FDA issued newly updated draft guidance on the use of decentralized clinical trials. The update was a clear sign of the Agency's commitment to ensure that lessons learned from the pandemic about the positive impact of such technologies would be applied in regard to clinical trial enrollment.

- The FDA also increased regulatory requirements to streamline local IRB processes and increase utilization of central IRBs. These requirements place pressure on organizations to improve their local IRB approval process or increase their reliance on commercial IRBs.13,14

The National Institutes of Health (NIH)

- The NIH released a Request for Information in spring 2021, seeking suggestions about ways it can advance racial equity, diversity and inclusion within all facets of the biomedical research workforce and expand research to eliminate or lessen health disparities and inequities.15

- The NIH's Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H) has stated clearly that diversity and health equity will be a key component of funding.

- The NCI and the Veterans Administration released an RFP April 3, 2023 for an Interagency Group to Accelerate Trial Enrollment including a focus on minority populations.16

The White House Office of Science Technology and Policy (OSTP)

- OSTP issued an RFI in late 2022. The RFI aims to acquire stakeholder input on the Clinical Research Infrastructure and Emergency Clinical Trials to address preparedness, equity, diversity and trust in science.17

The Government Accountability Office (GAO)

- A GAO Study on Cancer Clinical Trials and Federal Actions and Selected Non-Federal Practices to Facilitate Diversity of Patients, completed in December 2022, describes best practices to increase diversity in cancer clinical trials.18

Footnotes

1. Carlisle B, Kimmelman J, Ramsay T, MacKinnon, N. Unsuccessful trial accrual and human subjects protections: an empirical analysis of recently closed trials. Clin Trials 2015;12:77–83.

2. Steinberg JR, Turner BE, Weeks BT, et al. Analysis of Female Enrollment and Participant Sex by Burden of Disease in US Clinical Trials Between 2000 and 2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2113749. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13749

3. Lau SWJ, Huang Y, Hsieh J, et al. Participation of Older Adults in Clinical Trials for New Drug Applications and Biologics License Applications From 2010 Through 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):e2236149. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.36149

4. Woodcock J, Araojo R, Thompson T, Puckrein GA. Integrating research into community practice—toward increased diversity in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1351-1353. https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMp2107331?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed. May 2, 2024.

5. See Schwartz AL, Alsan M, Morris AA, Halpern, SD. Why Diverse Clinical Trial Participation Matters. N Engl J Med. 2023; 388:1252-1254. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp2215609. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2215609. Accessed August 3, 2023.

6. Woodcock J, Araojo R, Thompson T, Puckrein GA. Integrating research into community practice—toward increased diversity in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1351-1353. https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMp2107331?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed. May 2, 2024.

7. Mohan SV, Freedman J. A review of the evolving landscape of inclusive research and improved clinical trial access. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2022;113(3). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36536992/. Accessed August 3, 2023.

8. U.S. Congress website. H.R.1966 – Henrietta Lacks Enhancing Cancer Research Act of 2019. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1966/text. Accessed August 3, 2023.

9. U.S. Congress website. H.R.913 – Clinical Treatment Act. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/913/all-info. Accessed August 3, 2023.

10. U.S. Congress website. H.R.2617 – Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2617. Accessed August 3, 2023.

11. FDA Oncology Center of Excellence Project Equity website. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/oncology-center-excellence/project-equity. Accessed August 3, 2023.

12. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Conduct of Clinical Trials of Medical Products During the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency: Guidance for Industry, Investigators and Institutional Review Boards. https://www.fda.gov/media/136238/download. Accessed August 3, 2023.

13. Resnik DB, Smith EM, Shi M. How U.S. research institutions are responding to the single Institutional Review Board mandate. Account Res. 2018;25(6):340-349. doi: 10.1080/08989621.2018.1506337. Epub 2018 Aug 9. PMID: 30058382; PMCID: PMC6336442.

14. Federal Register. 2022 (Sept. 28); 87(187). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2022-09-28/pdf/2022-21089.pdf

15. National Institutes of Health website. NIH-wide strategic plan for diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/nih-wide-strategic-plan-diversity-equity-inclusion-accessibility-deia. Accessed August 3, 2023.

16. U.S. Veterans Affairs Website. RFA announcement. NCI and VA interagency group to accelerate trials enrollment (NAVIGATE): request for applications (RFA). April 3, 2023. https://www.research.va.gov/programs/csp/NAVIGATE-RFA.pdf

17. Wolinetz C, Sipes G. OSTP and NSC seek input on U.S. capacity for emergency clinical trials, research. 2022 (Oct. 25). The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (blog). https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/news-updates/2022/10/25/ostp-and-nsc-seek-input-on-u-s-capacity-for-emergency-clinical-trials-research/. Accessed August 3, 2023.

18. U.S. Government Accountability Office. Report to Congressional committees. 2022 (December). Cancer clinical trials: federal actions and selected nonfederal practices to facilitate diversity of patients. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-23-105245.pdf. Accessed August 3, 2023.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.