Bipartisan legislation and growth through public and private investment are transforming the behavioral health care delivery system. The rollout of several transformational programs, combined with increases in substance use, anxiety and depression secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic, exposed a shortage of providers nationwide (from an already-limited workforce). The rollout of the 988 Suicide and Crises Lifeline in July 2022, an escalated focus on mobile crisis-team services, standardization of inpatient and outpatient treatment programs, and an increase in substance-use disorder treatment programs all received bipartisan support and investment, furthering demand for behavioral health professionals.1, 2, 3

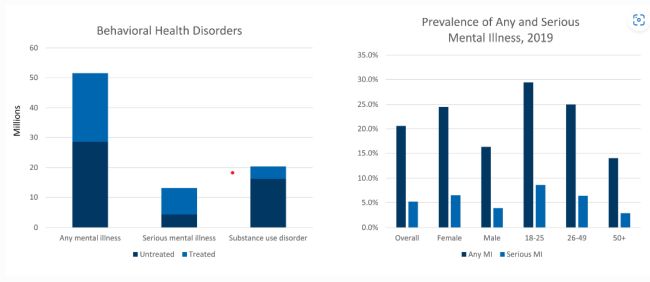

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased both the percentage of the population affected by anxiety and depression and the awareness of behavioral-health issues. Yet, treatment is lagging prevalence, as a shortage of therapists (psychiatrists, psychologists, and licensed clinical social workers) exists. Only 46.2% of patients aged 18 or older diagnosed with any mental illness are treated.4 Often, those treated only by primary care physicians ("PCP"s) have suboptimal outcomes.

This article discusses the prevalence of behavioral -health disorders, the size of the market, impact of comorbid chronic disease, opportunities for collaborative care, federal and state intervention, innovation in telehealth and emerging technology. Suggested next steps are also considered.

Rising prevalence

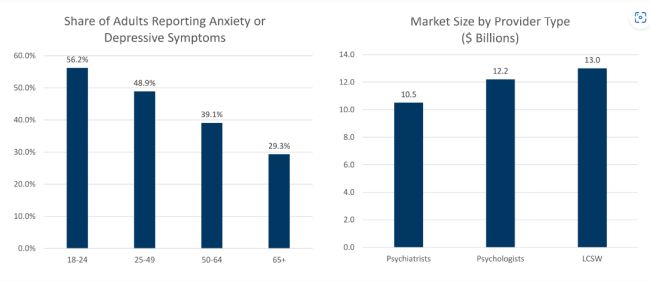

Behavioral-health disorders affected approximately 51.5 million adults aged 18 or older in the United States in 2019; 13.1 million (25.4%) have serious mental illness.5 More recent data highlight the dramatic rise of depression- and anxiety-related disorders since the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic. The average share of adults reporting symptoms of anxiety or depression reached 41.1% in January 2021; the pre-pandemic figure was 11.0%.6

Behavioral Health market characterized by its size and untreated patients

A large market with staff shortages

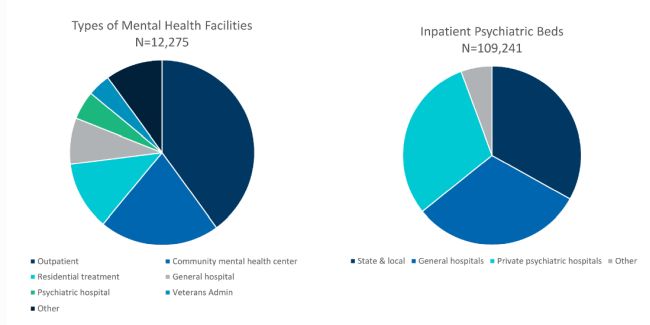

According to the National Mental Health Services Survey ("N-MHSS") in 2020, there were 12,275 facility survey respondents (87% of the eligible total) offering mental health services. Outpatient offices and Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics ("CCBHC"s) account for most facilities, followed by residential treatment centers and inpatient hospitals.7 General hospitals and psychiatric hospitals represent 13% of the total or 1,596 facilities.8 Private for-profit facilities make up 21% of the total.9

Outpatient facilities account for 40% of the total

There are 109,241 inpatient (non-residential) psychiatric beds in the United States: state and local (36,167), general hospitals (33,979), private psychiatric hospitals (32,945), Veterans Health Administration hospitals (2,872) and other sites of care (3,278).10 This equates to 42.3 beds per 100,000 population.11 A recent study suggests the need for at least 34.9 beds per 100,000 population (range: 28.1 to 41.7).12 The Treatment Advocacy Center suggests a range of 40 to 60 beds per 100,000 population.13

FTI Consulting built an outpatient market model based on a series of assumptions, including the number of patients seen by a clinician per day, the number of days in the week a clinician sees patients, a 48-week work year and revenue per visit; the number of psychiatrists, psychologists and licensed clinical social workers is drawn from the literature.14, 15, 16

The FTI Consulting model excludes inpatient services, marriage and family therapists and licensed professional counselors. We estimate a therapy market of $35.7 billion — a figure that excludes the development of therapy-related apps, e.g., meditation apps. There is a shortage of providers, particularly psychiatrists.17

Large market driven by growing demand for services, 2021

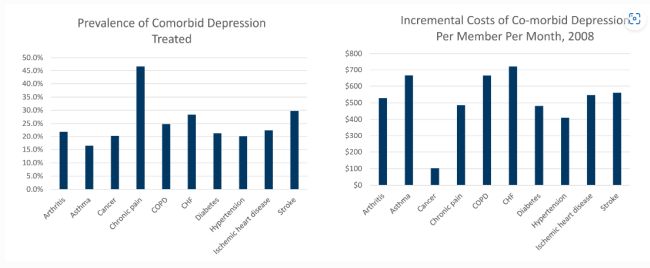

Chronic disease, behavioral health and incremental costs

Depression in patients with chronic conditions presents diagnostic challenges. Symptoms such as weight loss, fatigue, loss of appetite, sleep alterations and pain may reflect the underlying condition and not be indicative of behavioral-health issues. Alternatively, unexplained symptoms such as shortness of breath, dizziness, chest or abdominal pain, headache and back pain may occur in more than half of patients with depression or anxiety. Approximately 79% of anti-depressants are prescribed by PCPs, yet depression screening does not occur in most practices.18

Milliman Research published a report suggesting 30%-80% higher medical spending occurred for patients with chronic disease and depression compared to those with only chronic disease.19 The increase was noted in a wide variety of conditions. Similar results were obtained for patients with anxiety, a comorbid condition commonly associated with depression.20

Chronic disease and comorbid depression prevalence and incremental costs

A more recent Canadian study found higher resource allocation for patients with comorbid depression, including higher rates of hospitalization and emergency department visits, and a prolonged length of stay. The three-year median costs for patients with comorbid depression is $38,250, 72% higher than the control population without comorbid behavioral health issues.21

Collaborative care

The industry is focused on bringing collaboration between physician and mental health professionals. PCPs treat 60% of people with depression and dispense 79% of antidepressant medications, often with minimal, if any, support from psychiatrists.22 Depression is exceedingly common, as is the prescribing of antidepressants for 12.7% of persons aged 12 and over.23 According to Brightside Health Blog, "While a skilled psychiatrist might consider more than 30 different medications and over 300 different medication/dose combinations for a given patient, PCPs tend to prescribe from a short list of 1-3 widely used antidepressants for everyone."24 Depression management by PCPs is suboptimal.25

Primary care physicians often misdiagnose (50%-75% of the time), undertake incomplete clinical assessments, prescribe medications at insufficient dose levels relative to expert guidelines, inadequately monitor patients and fail to integrate therapy visits fully.26 Referral from primary care to psychiatry is often difficult.

Collaborative care involves a psychiatrist and behavioral care manager to optimize and coordinate care. Treatment goals are established, and a treatment plan is developed to meet those goals.27 Regular visits are required. Collaborative care is measurement-oriented (Patient Health Questionnaire-9) and utilizes a stepped-care approach.28 It is cost-effective.29

Legislative initiatives

The 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline was funded through three recent bills: The Omnibus bill, The American Rescue Plan Act ("ARPA") and the Safer Communities Act. Together, these bills provided states with $432 million to rollout the 988 Lifeline as an alternative to calling 911 and funded grant opportunities to establish mobile crisis teams and centers to divert treatment for a non-emergent situation away from the emergency room or local jail. These programs call for 24-hour crisis-line monitoring and immediate psychiatric screening by professionals trained in de-escalation of mental-health crisis situations.30

The Safer Communities Act also expanded the Medicaid demonstration for CCBHCs, for which participating states receive enhanced federal matching funds, from the current demonstration of 10 states to an additional 10 states every 2 years. CCBHCs are required to provide nine services either directly or through a designated collaborating organization, to coordinate care and follow evidence-based practices to receive a cost-based bundled rate. The demonstration, which started in 2017, has been extended several times and received bi-partisan support.31

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic exposed provider shortages and increased the prevalence and awareness of mental health issues, the federal government passed several transformational pieces of legislation. Most notably:

- The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act ("MHPAEA") of 2008, "prevents group health plans and health insurance issuers that provide mental health or substance use disorder (MH/SUD) benefits from imposing less favorable benefit limitations on those benefits than on medical/surgical benefits."32 The MHPAEA applies to group and individual health-insurance coverage.33 Criteria for medical necessity determinations must be made available by the plan administrator or health insurance issuer to any current or potential participant.34 Small employers (those with < 50="" employees)="" are="" exempt="" from="" the="" />35 The MHPAEA does not require coverage of mental health and substance-use disorder benefits; it applies to plans choosing to cover MH/SUD benefits.36

- The Affordable Care Act ("ACA") of 2010 mandates 10 essential benefits for coverage by health-insurance plans inclusive of mental health and substance use disorders. The ACA also eliminated the pre-existing-condition clause preventing those with MH/SUD from receiving treatment. Services that must be covered include inpatient, outpatient, intensive outpatient, partial hospitalization, residential treatment, emergency care and prescriptions. Benefits such as co-pays, co-insurance, deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums must be covered equally. The number of visits or hospital days should not be limited, unless similar limitations apply to most other medical illnesses under a plan. Prior authorization or medical-necessity reviews cannot be more restrictive than those for medical claims.37

- The Protecting Access to Medicare Act ("PAMA") of 2014, which authorized the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Service ("CMS") to develop a Medicaid demonstration of a sustainable, standardized model of care through CCBHCs with cost-based reimbursement rates.38

- The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA) of 2016 that authorizes appropriation of $181 million annually to respond to opioid abuse.39

- The Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) for Patients and Communities Act of 2018 to expand practitioner conditions of use for medication assisted treatment40

- The 21st Century Cures Act of 2016, which codified the creation of the Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality and the National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory.41,42

The resulting demand on current infrastructure and staffing levels has created shortages, exacerbated by the pandemic, and the resultant increases in wages and recruitment for qualified staff. Organizations are turning to innovative practices, also enhanced by the pandemic, including telehealth and emerging digital technology.

Rise of telehealth

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 saw telehealth utilization increase 63-fold among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, from 840,000 visits in 2019 to 52.7 million in 2020.43 A Fair Health analysis from July 2022 found that telehealth represented 5.3% of claim lines (services or procedures listed on an insurance form).44 Mental health conditions accounted for 63.5% of telehealth claim lines, with (clinical) social workers, psychologists and psychiatrists among the top five specialties using telehealth.45

Telehealth is convenient, accessible, and potentially engaging in real time. Clients are often able to schedule an appointment online. Among the available behavioral therapies are one-on-one therapy, group therapy, medication management and anxiety/depression monitoring.46 Several internet-based mental health (therapist, coaching) companies have emerged during the past few years.47,48,49

Emerging technology

Conversation assistants (known as chatbots) and text messaging applications are used to provide 24/7 patient support.50 "They can guide users through how they are feeling, help users challenge negative thoughts, suggest tools and resources, and engage them in evidence-based therapy techniques including mood tracking and mindfulness."51 Machine learning is utilized to provide responses based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy ("CBT"), how thoughts affect emotions and behaviors; Dialectical Behavior Therapy ("DBT"), a form of CBT focused on acceptance; and Interpersonal Psychotherapy ("IPT"), focused on improving interpersonal relationships.52 A mood tracker is often provided. Several chatbots have been developed.

Mental health applications have also been developed to provide care, convenience and 24/7 access. Focus areas include meditation, mindfulness, wellness, sleep and breathing exercises.53 De-stigmatization is emphasized.54 Care teams comprising psychiatrists, psychologists, licensed clinical social workers and/or coaches are accessed via a smartphone and deliver evidence-based care.55 Algorithms have been utilized for predictive monitoring.56

Private equity interest

During the past five years, there were nearly 100 private equity acquisitions in a highly fragmented market.57 Relatively few large independent practices exist, i.e., de novo practice creation may be required. Investments have been made in psychologist offices, psychiatric facilities, telehealth platforms and a wide variety of applications. Rising prevalence, combined with improving reimbursement driven by the Mental Health Parity Act has increased sector attractiveness.58 High rates of absenteeism and presenteeism contribute to employer interest and drive commercial reimbursement coverage in potential solutions.59

Therapeutic dimensions based on patient acuity include the category of therapist (coach, LCSW, PhD/ScD, psychiatrist), location of therapist (in-state), type of therapy (CBT, DBT, etc.), individual or group therapies, synchronous and asynchronous (mobile) delivery, in-person or virtual sessions, reimbursement coverage (in-network) and the experience of care. Capital efficient and balance sheet "light" providers are of particular interest.60 Venture capital investment totaling $4.5 billion in 2021 has been made in technology solutions for specific behavioral health issues.61 Several private equity platforms have integrated substance use disorders (SUDs) and eating disorders with behavioral health.

Provider implications and suggested next steps

- Monitor grant opportunities

- Prepare for new "feeders" of business from 988 and mobile crisis

- Expect increases in salaries and wages which will have to impact reimbursement rates

- Lobby for participation in the CCBHC program

Payer implications and suggested next steps

- Expect increased scrutiny of mental health parity through federal and state monitoring programs

- Expect increases in pricing trends due to higher demand for qualified workers

- Focus care management on evidence-based practices that continue to emerge through nationwide focus on standards of care quality and outcomes.

Commercial implications and suggested next steps

- Look for opportunities for investment in inpatient and outpatient care facilities

- Create feeder organizations from 988 and mobile crisis teams/centers

- Continue to innovate technology solutions that enhance customer experience, create provider efficiency and monitor outcomes.

Bottom line

Unmet needs in behavioral health are compounded by staff shortages. Opportunities exist to create behavioral health platforms and integrate primary care with psychiatric oversight, utilize virtual visits, manage prescriptions, and implement asynchronous digital technologies. Consolidation, especially in populated areas, remains a possibility, given the high level of fragmentation. A crisis of care exists, and telehealth is a partial answer.

Footnotes

1. "988 Suicide and Crises Lifeline." Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (last updated December 27, 2022), https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/988.

2. "National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crises Care Best Practice Toolkit: Mobile Crisis Team Services." Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, page 18 (2020), https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/national-guidelines-for-behavioral-health-crisis-care-02242020.pdf.

3. "Technical Brief: Census of Opioid Treatment Programs." National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors, American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence, Inc. and Opioid Response Network, page 10 (September 2022), https://nasadad.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/OTP-Patient-Census-Technical-Brief-Final-for-Release.pdf.

4. "Mental Health by the Numbers." National Alliance on Mental Illness (last updated June 2022), https://www.nami.org/mhstats.

5. Ibid.

6. Nirmita Panchal, Rabah Kamal, Cynthia Cox and Rachel Garfield. "The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use." Kaiser Family Foundation (February 10, 2021), https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/.

7. "National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS): 2020 Data on Mental Health Treatment Facilities." Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, page 15, Figure 1. Facility Type: 2020 (October 2021), https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35336/2020_NMHSS_final.pdf.

8. Ibid. at page 15, Figure 1. Facility Type: 2020.

9. Ibid. at page 13.

10. Ibid. at page 65 Table 3.3.

11. Ibid.

12. Christopher G. Hudson, et al. "Benchmarks for Needed Psychiatric Beds for the United States: A Test of a Predictive Analytics Model." International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (November 20, 2021), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8625568/.

13. "How Many Psychiatric Beds Does America Need?" Treatment Advocacy Center (March 2016), https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/backgrounders/how-many-psychiatric-beds-does-america-need.pdf.

14. Physician's Specialty Data Report. AAMC (2020). https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-largest-specialties-2019.

15. "How many psychologists are licensed in the United States?" American Psychological Association (June 2014), https://www.apa.org/monitor/2014/06/datapoint.

16. "Clinical Social Worker Demographics and Statistics in the US." Zippia (last visited October 7, 2022), https://www.zippia.com/clinical-social-worker-jobs/demographics/.

17. Stacy Weiner. "A growing psychiatrist shortage and an enormous demand for mental health services." AAMC News (August 9, 2022), https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/growing-psychiatrist-shortage-enormous-demand-mental-health-services.

18. Andres Barkil-Oteo. "Collaborative Care for Depression in Primary Care: How Psychiatry Could 'Troubleshoot' Current Treatments and Practices." Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine (June 13, 2013), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3670434/.

19. "Chronic Conditions and Co-morbid Psychological Disorders." Milliman Research Report, Figure 2 (2008), http://www.cbhc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/chronic-conditions-and-comorbid-RR07-01-08.pdf.

20. Ibid. at Figure 3.

21. Barbora Sporinova, MD; Braden Manns, MD; Marcello Tonelli, MD et al. "Association of Mental Health Disorders with Health Care Utilization and Costs Among Adults with Chronic Disease." JAMA Network Open (August 23, 2019), https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2748662.

22. Andres Barkil-Oteo. "Collaborative Care for Depression in Primary Care: How Psychiatry Could 'Troubleshoot' Current Treatments and Practices." Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine (June 13, 2013), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3670434/.

23. Laura A. Pratt, Debra J. Brody and Qiuping Gu. "Antidepressant Use Among Persons Aged 12 and Over: United States, 2011–2014." National Center of Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NCHS Data Brief 283 (August 2017). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db283.htm.

24. "Millions of people are on the wrong antidepressant: How to fix that." Brightside Health Blog (last visited October 13, 2022), https://www.brightside.com/blog/millions-of-people-are-on-the-wrong-antidepressant-how-to-fix-that/.

25. Andres Barkil-Oteo. "Collaborative Care for Depression in Primary Care: How Psychiatry Could 'Troubleshoot' Current Treatments and Practices." Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine (June 13, 2013), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3670434/.

26. Ibid.

27. Stephen M. Strakowski. "Managing Depression in Primary Care: A Step-by-Step Guide." Mecscape (September 10, 2015), https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/850499.

28. Andres Barkil-Oteo. "Collaborative Care for Depression in Primary Care: How Psychiatry Could 'Troubleshoot' Current Treatments and Practices." Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine (June 13, 2013), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3670434/.

29. Ibid.

30. "We Can All Prevent Suicide," 988 Suicide and Crises Lifeline. (last visited January 4, 2023). https://988lifeline.org/how-we-can-all-prevent-suicide/

31. SAMHSA CCBHC Expansion Grants: "No Cost Extension". QUALIFACTS. (last visited January 4, 2023). https://www.qualifacts.com/resource/blog/samhsa-ccbhc-expansion-grants-no-cost-extension/

32. "The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA)." CMS.gov (last visited June 16, 2022), https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Other-Insurance-Protections/mhpaea_factsheet#.

33. Ibid.

34. "Affordable Care Act Implementation FAQs - Set 5. The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008." CMS.gov (last visited June 14, 2022), https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Fact-Sheets-and-FAQs/aca_implementation_faqs5.

35. Ibid.

36. "The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA)." CMS.gov (last visited June 16, 2022), https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Other-Insurance-Protections/mhpaea_factsheet#.

37. "Affordable Care Act Implementation FAQs - Set 7, Question 3." Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (last visited January 4, 2023) https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Fact-Sheets-and-FAQs/aca_implementation_faqs7

38. "Section 223 Demonstration Program for Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics." Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration. (last visited January 4, 2023). https://www.samhsa.gov/section-223

39. "The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA)." Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America (CADCA). (last visited January 4, 2023). https://www.cadca.org/comprehensive-addiction-and-recovery-act-cara

40. "Implementation of the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention That Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act of 2018: Dispensing and Administering Controlled Substances for Medication-Assisted Treatment." Federal Register. (November 11, 2020) https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/11/02/2020-23813/implementation-of-the-substance-use-disorder-prevention-that-promotes-opioid-recovery-and-treatment#

41. "Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality." Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (last visited January 4, 2023). https://www.samhsa.gov/about-us/who-we-are/offices-centers/cbhsq

42. "SAMHSA to hold press call today on strengthening the use of science in behavioral health services." Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services. (January 11, 2018). https://www.samhsa.gov/newsroom/press-announcements/201801111145

43. "New HHS Study Shows 63-Fold Increase in Medicare Telehealth Utilization During the Pandemic." HHS.gov (December 3, 2021), https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2021/12/03/new-hhs-study-shows-63-fold-increase-in-medicare-telehealth-utilization-during-pandemic.html.

44. "Monthly Telehealth Regional Tracker, July 2022: United States." Fair Health (July 2022), https://s3.amazonaws.com/media2.fairhealth.org/infographic/telehealth/july-2022-national-telehealth.pdf.

45. Ibid.

46. "Telehealth and Behavioral Health." Telehealth.HHS.gov (last visited October 8, 2022), https://telehealth.hhs.gov/patients/telehealth-and-behavioral-health/.

47. Better Help (last visited October 13, 2022), https://www.betterhelp.com/.

48. Talkspace (last visited October 13, 2022), https://try.talkspace.com/online-therapy.

49. Ginger (last visited October 13, 2022), https://www.ginger.com/.

50. Nicole Owings-Fonner. "Fighting Loneliness and Anxiety: Can a Chatbot Provide Additional Support for Your Patients?" American Psychological Association Services, Inc. (August 2021), https://www.apaservices.org/practice/business/technology/tech-column/mental-health-chatbots.

51. Ibid.

52. Ibid.

53. Headspace (last visited October 18, 2022), https://www.headspace.com/.

54. "Listen to how Mindstrong is transforming mental health care." Mindstrong (September 21, 2022), https://mindstrong.com/blog/mental-health-podcast/.

55. Mindstrong (last visited October 19, 2022), https://mindstrong.com/what-we-do/.

56. Ibid.

57. Rebecca Springer. "Established Private Equity Healthcare Provider Plays." Pitchbook (December 27, 2021)

58. Kelsey Waddill. How Payers Are Increasing Access to Behavioral, Mental Healthcare Services: Payers are working toward achieving roader access to mental healthcare and behavioral healthcare services by reimbursing at higher rates and supporting primary care. HealthPayer Intelligence. (August 22, 2022). https://healthpayerintelligence.com/news/how-payers-are-increasing-access-to-behavioral-mental-healthcare-services

59. Paul E. Greenberg. "Major Depressive Disorders Have an Enormous Economic Impact." Scientific American (May 5, 2021), https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/major-depressive-disorders-have-an-enormous-economic-impact/.

60. Bailey Bryant. "Private Equity to Fuel Behavioral M&A in 2021, With Outpatients Models Driving Demand." Behavioral Health Business (January 29, 2021), https://bhbusiness.com/2021/01/29/private-equity-to-fuel-behavioral-ma-in-2021-with-outpatients-models-driving-demand/.

61. Khadeeja Safdar and Gregory Zuckerman. "Buyout firms and venture capitalists pile into mental health clinics." Private Equity News (May 10, 2022), https://www.penews.com/articles/buyout-firms-and-venture-capitalists-pile-into-mental-health-clinics-and-therapy-startups-20220510.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.