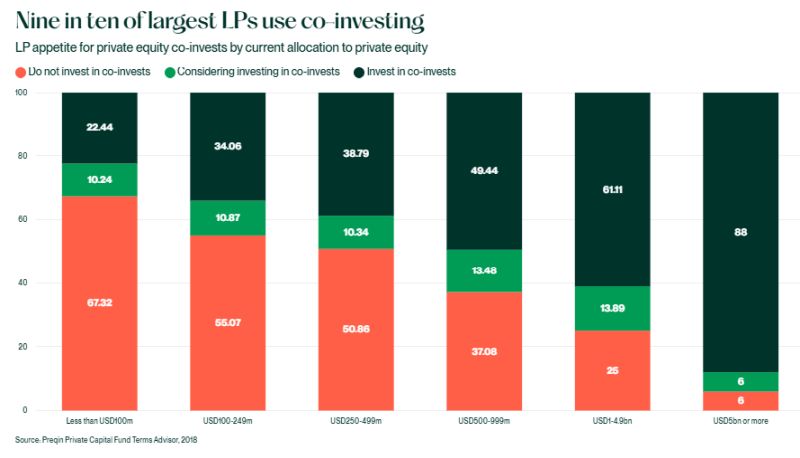

A challenging fundraising environment, the rise in M&A activity and the capital requirements necessary to bridge funding gaps are key developments which have led fund managers to increase their offering of co-investment opportunities, while simultaneously using these co-investments to bolster their relationships with existing and new investors.

The resulting trend is that a significant proportion of investors are now participating in blind-pool funds primarily to gain access to co-investment opportunities. This underscores the growing importance of distinguishing what co-investment structures and their terms consist of, in order to successfully avail of the returns and economics as an investor, and to maintain control over the allocation of capital as a manager.

1. What is a co-investment and how is it structured?

1.1 What is a co-investment?

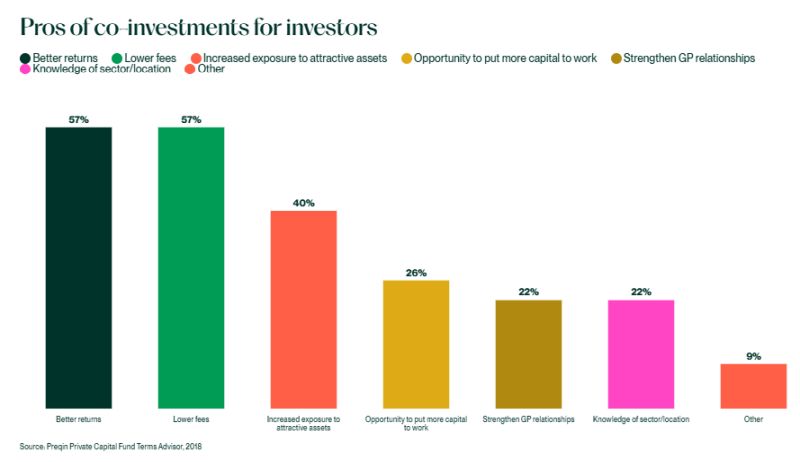

(a) A co-investment is an investment by limited partners (LPs) in a specific opportunity alongside, but distinct from, the flagship fund. These arrangements have seen a resurgence and are being used across a range of sectors such as real estate, energy and utilities, industrials, healthcare, and TMT. Aside from strategic relationship building and diversification advantages for managers, from an LP perspective, the benefits include exposure to an attractive deal pipeline which otherwise has limited availability, lower fees and carried interest on a blended basis, the opportunity to put more capital to work, the ability to penetrate new and lucrative market sectors, and increased transparency regarding the rate of investment deployment and the strategic focus of the fund (including specific industries or geographic regions).

(b) Historically, co-investments were deployed for larger transactions requiring more capital or where the main fund (Main Fund) decides not to pursue the entire investment due to factors such as concentration limits.

1.2 How is a co-investment structured?

(a) Co-investment vehicles are typically formed to provide capital for a single investment and can be established in advance to permit accelerated participation by investors/LPs. These vehicles often invest alongside the standalone Main Fund or the multi-fund arrangements in identified investment deals, with a separate vehicle for each investment. Participants often include existing fund limited partners, strategic investors, and other third parties (such as relationship investors).

(b) Basic structuring options are:

- A fund-of-one for a specific investor

- An investment vehicle set up for multiple investors (i.e., a co-investment fund)

- Overall multi-fund allocation arrangement (e.g., strategic co-investment/topco relationship)

- A direct investment in the target by the co-investor (raises voting/control/conflict issues)

(c) The structure to be used will depend on a number of factors—balancing issues relating to governance/control, economics, conflicts, scope of participation, and tax or regulatory status of the particular investors (e.g., any UBTI/ECI/ERISA considerations).

(d) Where it is a dedicated sidecar vehicle or strategic relationship, the vehicle is usually established in advance—a "standing vehicle"—to permit participation in multiple future co-investments on a more accelerated and streamlined timeframe. This provides investors with more systematic participation rights but raises allocation, conflict, fiduciary, expense sharing, and disclosure issues. The vehicle can be a single investor (e.g., a strategic, segregated managed account, or fund-of-one) or a multiple investor pooled vehicle. The strategy varies—for example, some are a fund designed to simply co-invest alongside the Main Fund in all investments where needed, others can have a specific strategy to only co-invest alongside the Main Fund for particular types of assets.

(e) Where the vehicle is established to permit participation in multiple deals, investors may be permitted to opt in or opt out (or a combination of both) on a deal-by-deal basis, such as a "pledge fund" structure (i.e., where an investor makes a "soft" commitment and joins investment opportunities at their discretion). These structures can be attractive to co-investors as they can provide a greater level of flexibility and control. From a manager's perspective, these structures can become complex, with no guarantee of investor participation (albeit managers will typically include a "three strikes" provision, allowing them to withdraw investors, or otherwise treat them differently, if they repeatedly reject opportunities). Pledge fund structures can be useful to create a track record in a new market or build new relationships but are typically used by managers as part of a broader approach to co-investments.

(f) For investors, co-investment arrangements are often offered at reduced or no management fee or carried interest (and there are differences in market practice depending on the asset class). LPs often negotiate co-investment rights in connection with admission to the Main Fund, and managers often agree to acknowledge LP interest in the co-investment through a side letter, although allocations remain at the discretion of the manager and depend on various factors and the strength of bargaining power between the parties.

(g) Co-investments are being executed prior to the signing stage, rather than following a post-syndication process. This shift has resulted in pressure in completing deals in a shorter timeline. There is also a growing emphasis on issues such as Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) filings, including those required by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). Such regulatory analysis often needs to be conducted at very short notice, hence the importance of timely and thorough due diligence cannot be underestimated.

(h) It is important to highlight the programmatic approach to co-investing witnessed among large asset managers. These managers are increasingly offering co-investment opportunities in conjunction with their primary funds. Such arrangements are often negotiated in advance for the sake of expediency, establishing the key parameters and types of deals to be invested in for the future, as well as quick action "opt-in and opt-out" rights for investors.

1.3 What are the types of co-investment rights?

(a) Soft rights/expressions of interest

Co-investors have no legal right to co-investment opportunities and manager retains discretion to allocate.

(b) Pre-emptive rights

These rights allow co-investors to invest in new opportunities before they are offered to external parties, providing them with a preferential position.

(c) Tag-along rights

These rights enable co-investors to join in on investments in which the Main Fund is participating, ensuring they can benefit from the same opportunities.

(d) Drag-along rights

These rights allow the Main Fund to compel co-investors to participate in an investment, ensuring alignment and collective action. This is less commonly seen unless a standing vehicle (as mentioned in section 1.2) is set up in advance.

1.4 What are the types of exit rights afforded to co-investors?

(a) Typically, co-investors are expected to exit the underlying investment at substantially the same time and on the same terms, subject to legal, regulatory, tax, or other similar considerations.

(b) That said, LPs are increasingly seeking to negotiate bespoke exit mechanisms to achieve greater flexibility, liquidity, and control over their co-investments. A few examples of such exit rights include:

(i) Special disposition rights: In a

single asset co-investment in the real estate/infrastructure

context, co-investors may negotiate the right to be consulted prior

to a disposition of the

underlying investment by the co-investment vehicle. In other cases,

the manager is required to hold the underlying investment for a

pre-agreed lock-in period. If the manager subsequently desires to

cause the co-investment vehicle to sell the underlying investment

during the lock-in period, the consent of the co-investors is

required to be obtained prior to the disposition. It is

relatively uncommon for the co-investors to be able to

affirmatively direct the manager to sell the underlying interest to

a third party, as the manager is responsible for the investment

management decisions in respect of the co-investment vehicle.

(ii) Tag-along rights: Co-investors may negotiate tag-along rights pursuant to which such co-investors are allowed to exit their interest in the underlying investment at the same price and on the same terms as the Main Fund.

(iii) Distributions in-kind: Co-investors may negotiate the right to receive in-kind distributions of the underlying securities under certain pre-agreed circumstances. This allows co-investors greater control over exits where there is a difference in the time horizons/holding periods of the manager and the co-investor. In a venture capital/private equity context, this may involve obtaining the relevant consents in accordance with the shareholders' agreement of the underlying portfolio company. Such rights are typically negotiated where it is expected that the underlying portfolio company may achieve an IPO.

(iv) Secondary sales: Co-investors may seek to enhance their flexibility to transfer their interest in the co-investment vehicle to third parties to facilitate an early exit for themselves. Managers may potentially agree to (not unreasonably) withhold their consent to the transfer by the co-investor of its interest in the co-investment vehicle. While managers may be agreeable to such softer consent mechanisms where all (or a substantial portion) of the co-investor's capital commitment is drawn down immediately following closing, managers often resist the request for the economic terms (including a discount to the management fee and carried interest) to be transferable by the co-investors to a third party, given that these terms have often been offered by the manager to the co-investors with a view to strengthening the relationship between the manager and the co-investor.

(v) Put option: While this route is

relatively uncommon, in the private credit context, where the

commercial arrangement is for the manager to provide certain

minimum return guarantees to co-investors, the manager may agree to

grant a put option to co-investors pursuant to which the

co-investors may require the manager or its affiliate to buy back

the interest of the co-investors in

accordance with a pre-determined formula, in order to ensure that

the co-investor receives a minimum return on its investment.

2. What are the conflict issues in co-investments?

2.1 Main conflicts arising within co-investment arrangements

(a) Governance

Co-investment vehicles typically do not have a Limited Partner Advisory Committee and follow the decisions and governance structures established by the Main Fund. This approach simplifies decision-making processes and ensures consistency in investment strategy, as the co-investment vehicle relies on the expertise and governance of the Main Fund. It is key to avoid LPs in co-investment vehicles from blocking decisions of the Main Fund. Present trends indicate that investors are displaying an increased appetite for governance rights, which in turn creates operational, practical, and conflicts issues.

(b) Disclosure issues

If a co-investment vehicle is established subsequent to the formation of the Main Fund, the manager must consider whether the Main Fund can accommodate a particular co-investment before directing an investment to a co-investment vehicle. If a co-investment vehicle is established simultaneously with the Main Fund, the manager should assess the fiduciary and other duties owed to the investors in the co-investment vehicle prior to such vehicle making any co-investments.

(c) Allocation of investment opportunities

The Main Fund generally has the primary right to make investments before offering remaining opportunities to co-investors. Co-investors are given the chance to invest alongside the Main Fund only after the Main Fund has allocated its portion. Potential investors should be evaluated, taking into consideration any fund documentation requirements and any private placement regulations that need to be complied with such as the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive in Europe and the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 in the U.S. The fund documents such as the Limited Partnership Agreement and side letters should also be reviewed for the purpose of determining the manager's allocation obligations, as there may be a notification obligation to the Limited Partner Advisory Committee/LPs if the manager allocates opportunities away from the Main Fund.

(d) Warehousing by the Main Fund

Warehousing refers to the practice where the Main Fund temporarily holds an investment until it is syndicated to the co-investment fund. During this period, the co-investment fund may be required to pay interest to the Main Fund to compensate the Main Fund for the cost of capital, thereby ensuring that the Main Fund is not disadvantaged due to capital being tied up during this period. If the Main Fund incurs borrowings to warehouse the investment (e.g., by drawing down on a sub-line), such interest costs should ideally be borne by the co-investors. The purchase price paid by co-investors would generally include the carrying/interest costs.

(e) Expense sharing

Expenses that relate to the management and operation of investments are typically shared on a pro-rata basis between the Main Fund and co-investors based on the relative capital invested. Broken deal expenses, incurred from deals that do not close successfully, are ideally shared pro rata but may sometimes be borne solely by the Main Fund.

(f) Investment and divestment

Investments and divestments can be made simultaneously and under substantially similar terms and conditions for both the Main Fund and co-investors, subject to legal, tax, and regulatory requirements. This alignment ensures that all parties have their interests synchronized, reducing potential conflicts and ensuring fairness. Divestments can also be made on a pro-rata basis, whereby both the Main Fund and co-investors divest in proportion to their respective holdings.

2.2 Best practice for addressing conflict issues

(a) Adopt formal written policies on allocation of co-investment opportunities and expenses

(i) Managers should implement formal written policies to ensure transparency in the allocation of co-investment opportunities and broken-deal expenses. Failure to establish such policies and procedures constitute a breach under the U.S. Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Standing coinvestment vehicles typically require co-investors to bear their pro-rata share of broken-deal expenses based on their expected investment amount, with allocation decisions made in good faith by the manager.

(ii) A robust and detailed co-investment policy should also be adopted by the fund manager, clearly identifying the decision-makers and the criteria for co-investment allocations. Additionally, the policy should include a process for contemporaneously documenting the basis for these allocation decisions.

(b) Review and update investor disclosures on co-investments

(i) It is critical to regularly review and update investor disclosures regarding co-investments. Generic disclosures about the possibility of co-investments may be inadequate, especially when significant co-investment opportunities are offered to some but not all fund investors. Disclosures should be consistent with the Limited Partnership Agreement, any side letters, offering documents, Form ADV and Due Diligence Questionnaire (DDQ) responses. Disclosures should also identify any prior agreements or commitments to provide coinvestment opportunities to certain investors and explain how these affect allocation decisions. Ideally, these disclosures should be provided to all relevant investors before they commit to invest. However, it remains to be seen whether in practice managers widely adhere to the transparency requirements for such disclosures.

(ii) This trend of investors requiring enhanced transparency as described can also be seen in their demands for board seats and for greater input in co-investment decisions. While such involvement can provide investors with more control and insight, such control and input by investors must be carefully considered and structured to comply with FDI regimes and other regulatory requirements. Balancing investor demands for a seat at the table with regulatory compliance is critical to avoid potential legal and operational challenges.

3. What are the differences in fund terms between a main fund and a traditional passive tagged co-investment?

3.1 Investment strategy and fees

Main Funds typically invest in a diversified portfolio across various sectors, stages, geographies, and strategies, whereas co-investment funds usually focus on a single investment or a few investments alongside the Main Fund often in the same sector, stage, geography, and strategy. Main Funds generally charge higher management fees (1–2% of committed capital/ net invested capital) and performance fees or carried interest (around 20% of profits above a hurdle rate). In contrast, co-investment funds often have lower or no management fees and carried interest, although they may charge an upfront administrative fee (0.5–2%) if no management fee is applied.

3.2 Commitments and expenses

Main Fund LPs commit a certain amount of capital, which is called upon over a specified investment period, with expenses outlined in the Limited Partnership Agreement. Co-investment funds base commitments on deal size and expected fees and expenses (fees and expenses could be potentially outside of commitments). Organizational expenses in Main Funds are capped, while co-investment funds may not have such caps on organizational expenses.

3.3 Governance and rights

Main Funds typically have a Limited Partner Advisory Committee comprising influential LPs who are consulted on conflicts, valuation, and other matters, whereas co-investment funds usually rely on the Main Fund's Limited Partner Advisory Committee. Key person provisions and manager removal rights are generally aligned with the Main Fund, and co-investment funds often follow the Main Fund's exit strategy, with limited influence over the timing and mode of exits. Co-investment funds may have tag-along rights on exits, ensuring they sell pro rata and on similar terms as the Main Fund.

3.4 Timing

(a) For the Main Fund, usually, there will be multiple closings over a period of 12—18 months. The manager will conduct an initial closing once a minimum threshold of capital contributions is reached, allowing the Main Fund to begin making investments while continuing to raise capital. Each closing brings in new investors who commit under the same terms as those in previous closings, although they must pay equalization interest.

(b) For the co-investment fund, typically there will only be one closing; if there is insufficient time, there can be multiple closings, but the offering period will be more restricted (e.g., three–six months). Where the offering period is particularly short, there will typically be no adjustment for equalization interest.

(c) Given the differences set out above, it is crucial to ensure that co-investment terms are closely aligned with those of the Main Fund to maintain consistency and coherence in investment strategies and outcomes.

4. How do co-investments interplay with continuation funds?

(a) A continuation fund is a vehicle set up by a manager to acquire one or more assets from an existing vehicle currently managed by the same manager. The intention is to provide liquidity to LPs in the existing vehicle by finding new investors to underwrite the asset(s), while ensuring that the manager has a longer runway to manage and achieve an exit for the asset(s). Many LPs see similarities between co-investment funds and continuation funds, as both types of structures typically allow LPs to conduct due diligence on a specific asset before investing (as compared to a blind pool fund), and both structures typically have lower management fees and carried interest (as compared to a blind pool fund). However, there are also key differences as the return profile of assets in a continuation fund may be different than that of a co-investment fund, since the assets housed in a continuation fund may be perceived as being at a more mature stage (or closer to exit).

(b) Separately, LPs who seek both liquidity and favorable investment terms may be faced with the choice between selling their co-investment at a potential discount or rolling the co-investment into a continuation fund, with the latter often coming with its own management fees and carry rates.

(c) In addition to concerns about incurring fees when being rolled into a continuation fund, LPs are worried about several other factors that come into play following these manager-led transactions, including:

- The tenor of the investment and how long the investment is going to be held/get extended

- The LP's relationship with the manager may have changed and the ensuing impact of this shift in dynamics

- There may have been changes to the asset that is the subject of the co-investment

(d) As such, the LP's approach to manager-led continuation funds is not a one-size-fits-all. If the continuation fund affects the co-investing LP's asset, LPs are requesting the same approval rights as the Main Fund. Where co-investing LPs want the option to roll, they will generally want to do so on the same terms as will have applied to the original co-investment. Some LPs regularly request side letters that explicitly prevent the co-investing LP from being dragged into a continuation fund. Note that some co-investing LPs may be restricted by internal policy from investing into continuation funds.

5. Key takeaways

On the one hand, co-investments offer a unique opportunity for LPs to invest alongside Main Funds and to target desirable and lucrative investments in select companies or assets, thus strengthening relationships with managers and providing exposure to exclusive opportunities with potentially lower fees. The flipside is that these co-investment arrangements bring their own set of complexities, including governance issues, conflicts of interest, and the push by investors for clarity and transparency regarding allocations. By adopting best practices such as formal written allocation policies, regular updates to investor disclosures, and careful consideration of the interplay with continuation funds, managers and LPs can fully maximize the advantages of the current hot market for co-investment arrangements.

To view the original article click here

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.