For years, companies have opted to include mandatory arbitration provisions and class action waivers in their website terms of service to reduce the cost of dispute resolution and risks of consumer class actions. Recently, however, plaintiffs' firms have tried to capitalize on these arbitration provisions—and the massive per-claimant fees that the leading arbitration providers impose on business—by pursuing mass arbitrations. The strategy is to threaten to file (or actually file) thousands of arbitration demands—and then use the arbitration fees as settlement leverage. In response, many companies have updated their online terms and dispute resolution provisions to mitigate the prohibitive costs of mass arbitration.

But this raises the question of how to bind users to these updated provisions. A recent decision out of the Southern District of New York offers guidance on what works, and what does not.

The case is Brooks v. WarnerMedia Direct, LLC (No. 23-cv-11030), and the decision can be accessed here. Five former subscribers of HBO Max (now Max) claimed that HBO Max had violated the Video Privacy Protection Act ("VPPA") by sharing their identity and viewing habits with Meta. There was no dispute that the claims were subject to arbitration. The issue was which version of HBO Max's arbitration agreement applied.

When the subscribers created an account with HBO Max, they assented to arbitrating their disputes before the American Arbitration Association ("AAA"). However, HBO Max subsequently updated its terms of use to select National Arbitration and Mediation ("NAM") as the arbitral forum—presumably because it preferred NAM's fee schedule over AAA's (which was draconian at the time, but has since been revised).

The subscribers—likely hoping to use AAA's exorbitant fee schedule as settlement leverage—filed their VPPA claims with AAA, notwithstanding the updated terms. AAA declined to administer the arbitration. The subscribers then moved to compel arbitration at AAA, and HBO Max cross-moved to compel arbitration at NAM. The key issue was whether HBO Max had bound these subscribers to its updated arbitration provision.

To answer this question, the court applied the established legal test: Did the subscribers receive clear notice of the updated terms? If so, did they assent to them?

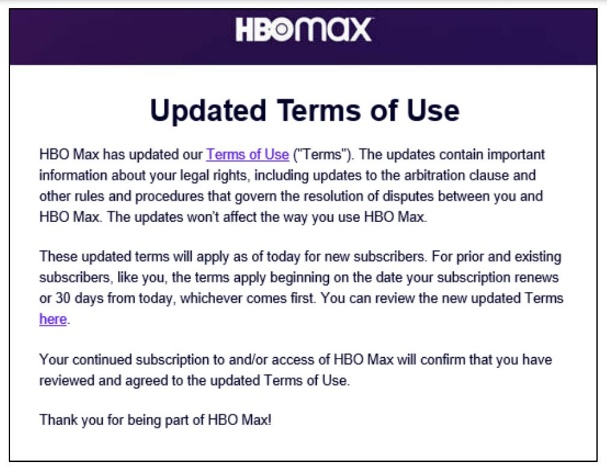

As to the first question, the subscribers agreed they'd received notice of the updated terms. HBO Max had sent them an email, which stated, "Your continued subscription to and/or access of HBO Max will confirm that you have reviewed and agreed to the updated Terms of Use":

As to the second question, the court had much to say, providing helpful guidance of what counts as valid and binding assent, and what does not.

After receiving the email notice, what the subscribers did next varied.

Some of the subscribers clicked the link in the email to view the updated terms. But this, the court found, is not enough to constitute assent, as it puts the cart before the horse. A user must be able to review updated terms before agreeing to them, so the antecedent act of clicking a link to view those terms does not amount to assenting to them.

Some of the subscribers also had subscriptions that they allowed to continue after the updated terms took effect. In other words, they never actively cancelled their subscriptions, which ended on the expiration date. HBO Max argued that by allowing their subscriptions to continue, those subscribers assented to the updated terms. But the court said not so fast: A user must take some "action" to assent, and all that these subscribers did was take no action.

There were, however, a few possible "actions" the subscribers might have taken that would constitute assent, so the court ordered discovery into the matter.

First, some of the subscribers may have used HBO Max as "authorized users" on someone else's account. This, the court said, would be enough, and ordered discovery on this issue.

Second, some of the subscribers may have clicked "Start Streaming" after logging into their account. In addition to the email notice, HBO Max had also placed a pop up on its platform that said, "By clicking 'Start Streaming,' you agree to the [updated terms]." Although the court found that logging in alone is not enough to show assent, logging in and clicking "Start Streaming" would be. The court ordered discovery on that issue as well.

Despite going through great lengths to update its terms, HBO Max is still embroiled in a fight over whether they are enforceable. While you can't guarantee a user will be bound by new terms, you can take steps to maximize those chances. It's critical that a user do something to show assent—mere receipt of an email with a link to the updated terms is likely insufficient unless the user continues to access the website's services or clicks a confirmation of assent. An attorney can help you incorporate valid touchpoints of assent into your user flow.

This alert provides general coverage of its subject area. We provide it with the understanding that Frankfurt Kurnit Klein & Selz is not engaged herein in rendering legal advice, and shall not be liable for any damages resulting from any error, inaccuracy, or omission. Our attorneys practice law only in jurisdictions in which they are properly authorized to do so. We do not seek to represent clients in other jurisdictions.