The Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive ("CS3D") was finally published on 5 July 2024, concluding a long and unprecedentedly turbulent legislative process. Businesses now have the certainty they need to start assessing whether they are in scope, and if so, what they need to do to comply with the demanding due diligence obligations under the law, and by when.

Somewhat less controversially, the EU has also recently enacted a range of other measures with serious implications for businesses and their supply chains. Though each is narrower in its scope than CS3D, the nuances in application will need to be understood by anyone impacted. Measures such as the new Batteries Regulation (replacing the 2006 Directive) incorporate active due diligence and traceability requirements in supply chains for products being placed on the EU market. The Deforestation Regulation will cover a range of commodities and finished products derived from them, which are linked to deforestation or forest degradation. Such products may not enter the EU market (or be exported from it) unless the importer or exporter can prove that the products are unconnected to such harms.

A further expansion to the growing body of supply chain laws is the EU's Forced Labour Products Regulation (the "FLP Regulation") - a seminal regulation aimed at tackling forced labour within supply chains, regardless of the type of product involved. The FLP Regulation is in the final stages of the legislative process with just formal approval outstanding (the draft approved by the European Parliament in April is not expected to change significantly).

Taken together, this new wave of legislation will have a significant impact on companies that operate in the EU, by requiring them to first gain transparency over and then to actively manage the human rights and environmental aspects of their own business, products and supply chains.

Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive

Who?

The scope of the Directive was considerably reduced over the course of negotiations with the final scope expected to impact only around 5400 of the largest companies. However, both EU and non-EU companies can be directly in the scope of the Directive.

Scope of CS3D

For EU entities:

individually or, in the case of an ultimate parent, on a

consolidated basis, a) more than 1000 employees; and b) a net

worldwide turnover of more than EUR 450 million in the last

financial year.

For non-EU entities: individually or, in the case of an ultimate parent, on a consolidated basis, net turnover of more than EUR450 million in the EU in the financial year preceding the last financial year.

"Company" in the context of CS3D is interpreted broadly, and the definition includes a long list of regulated financial undertakings including investment firms, AIFMs, UCITS management companies, insurance undertakings and payment institutions. AIFs and UCITS undertakings themselves are not in scope.

Similarly to the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive ("CSRD"), the scope of CS3D is limited to certain corporate forms, by reference to the lists in Annexes I and II of the Accounting Directive 2013/34/EU and third party (though CS3D is broader than CSRD).

When?

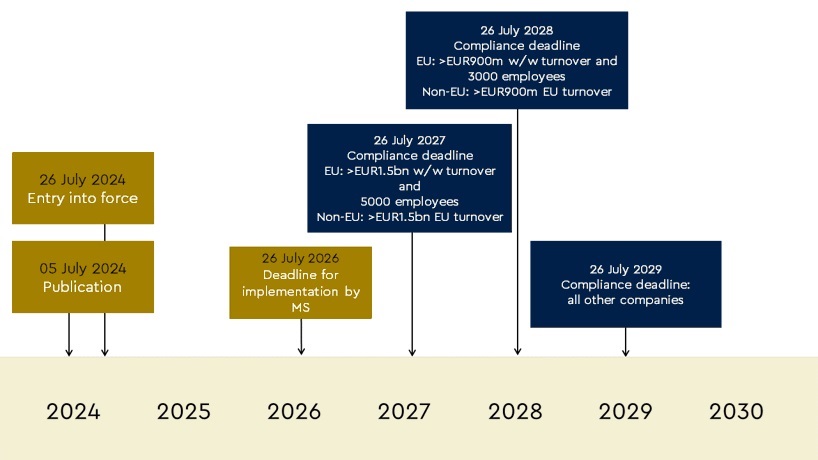

A further concession made to Member States during the drafting process was a staged implementation, with only the largest companies being subject to CS3D within the next 3 years. Most companies will have 5 years to arrange their businesses for full compliance with CS3D.

Companies in the scope of the earlier, 2027 and 2028, compliance deadlines may already be subject to supply chain obligations in the EU, considering that the French Duty of Vigilance Law applies to companies with over 5000 employees in France and the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Law (LkSG) applies to companies with over 3000 employees (reduced to 1000 as of 1 January 2024).

It is worth noting that for EU companies, the application dates are assessed according to the business's turnover (and as applicable employee numbers) in the financial year preceding the compliance deadline. Therefore, for many companies with financial years aligned to the calendar year, they will assess their exposure to CS3D for the first time by reference to accounts filed as at 31 December 2026 (for the largest companies subject to the first compliance deadline). By contrast, non-EU companies must assess the thresholds according to "the financial year preceding the last financial year" prior to the compliance deadline. Therefore, a UK or US parent company must assess its exposure to CS3D as at 31 December 2025 for the first time, providing at least a longer runway for compliance measures to be put in place.

What?

The premise of CS3D is straightforward: understand and control your supply chains, take responsibility for human rights and environmental harms that occur within them. In practice, the Directive lays down many prescriptive elements to this process, without beginning to scratch the surface of the complexity of putting it into effect.

1. Policies

CS3D requires businesses to formalise their approach to due diligence in a formal policy. The policy must comply with the specific elements set out in the Directive, such as outlining the company's long-term approach to due diligence, and including a code of conduct applicable to the business and its subsidiaries, and to be extended to business partners in the event that they are connected with adverse impacts.

2. Identify adverse impacts

Businesses must assess their own operations, those of their subsidiaries, and, where related to their "chain of activities", those of their business partners in order to identify adverse impacts.

Chain of activities

CS3D's equivalent concept to CSRD's "value chain", chain of activities covers business relationships relating to the production of goods or provision of services by the business, both direct (first tier) and indirect (second tier and above). For products, relationships both upstream and (in some cases) downstream of the business are included, whereas for services only upstream relationships are included (for now). This fact is particularly important for the financial services sector, as it is the mechanism by which their lending and investment activities are excluded from the scope of the due diligence obligation.

Identifying impacts is expected to be a two stage process – the first stage may well be conducted without the involvement of business partners, identifying risk hot spots potentially based on public and internally available information. The second stage should be an analysis of the specifics of the business relationship to ensure that the risk prevalent in that industry or geography is not actually materialising in the business relationship in question.

3. Act

The business must take "appropriate measures" to ensure that identified potential adverse impacts do not actually arise, and that actual adverse impacts are mitigated or ceased.

What impacts are covered?

Both environmental and human rights adverse impacts need to be identified, by reference to the list of international conventions in the annex to CS3D. On the environmental side, these are relatively limited, covering topics such as biodiversity, movement of waste and hazardous chemicals. On the human rights side, however, the list is more comprehensive, covering everything from freedom from torture, forced and child labour, right to fair wages and freedom of association. It also includes measurable environmental degradation which has a significant impact on persons by way of, for example, substantially impairing their ability to use land for food or access safe drinking water.

Appropriate measures will depend on the circumstances of the particular case, including whether the business itself caused the impact or how much influence it has over the entity which caused the impact.

Some of the "appropriate measures" listed in CS3D have been controversial – these include in particular the requirement to put in place contractual clauses to apply the business's code of conduct to the partner in question, to ensure the partner's compliance with it, and potentially extend its application to further sub-contractors or sub-suppliers. This has been viewed as a quick and easy way for businesses to push down the compliance burden to business partners including potentially SMEs, who are least able to bear the burden (though the business retains responsibility for verifying compliance). The European Commission will publish model clauses for this purpose, and CS3D itself foresees that contractual clauses used in contracts with SMEs must be fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory.

As a last resort, businesses may be required to suspend or terminate business relationships where adverse impacts cannot be prevented or adequately mitigated. This disengagement can be problematic where it is concentrated on many suppliers in a specific geographic area, as it then has the potential to affect responsible businesses as well as those with problematic practices, and by extension whole communities who may depend on trade with international businesses for their livelihood.

4. Remediate

Actual adverse impacts must be remediated, which may involve the business providing financial or non-financial compensation to affected persons, in proportion to its responsibility for the impact. The Commission will publish guidance on appropriate measures for remediation (amongst many other things).

5. Stakeholder engagement

The Directive requires that businesses carry out "meaningful engagement" with stakeholders - a broad term which including its employees, employees of its subsidiaries, trade unions, consumers, civil society organisations and others. This must occur at several junctures through the due diligence process. To be meaningful, existing human rights frameworks describe an interactive, two-way communication process with good faith on both sides.

6. Complaints process

The business must establish a fair, accessible and transparent process for receiving and dealing with complaints, available to natural and legal persons affected or potentially affected, by an adverse impact, as well as their legitimate representatives such as NGOs. Separately but related, persons with substantiated concerns can submit them to the national Member State competent authorities who may then investigate whether the business has failed to discharge its legal obligations.

7. Monitor

The due diligence process must be dynamic – for example the due diligence policy must be refreshed at least every 2 years. The process must be monitored and refined to ensure that it is adequate and effective in preventing human rights and environmental adverse impacts from occurring.

8. Communicate

The business must communicate on matters covered by CS3D in an annual statement. However, for businesses already reporting under CSRD, there is no additional reporting obligation. For businesses not covered by CSRD (possible in particular for large businesses with revenue in the EU but without a legal presence), the form of the annual statement is to be determined by the Commission, but is envisaged to align (to a greater or lesser degree) with the reporting standards under CSRD.

Climate transition plan

A further requirement of CS3D is for businesses in its scope to put in place a climate transition plan on a best efforts basis, aligned with the Paris Agreement target of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, as well as the EU's goal of being climate neutral by 2050. The plan should also limit companies' exposure to coal, oil and gas related activities. The Directive goes on to specify what the plan should contain, including both long term and interim targets for scope 1 and 2 emissions reductions as well as all significant categories of scope 3 emissions, where appropriate.

The requirement to put in place a transition plan has proved to be at least as concerning to certain businesses as the due diligence based requirements. To date, transition plan requirements have solely focused on disclosure. The largest companies in the scope of CS3D will need to consider how to align their business model and strategy with climate goals which are increasingly being viewed as unattainable, meaning that their individual commitments may need to be ever more ambitious.

Forced Labour Products Regulation

The FLP Regulation forms part of a growing body of international legislation requiring organisations to take positive measures to identify and minimise forced labour occurring in their supply chains. For example, the United States' Tariff Act and Canada's Custom Tariff Act both preclude importing goods if there is reason to believe that they have been created with forced labour. The US Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act also aims to prevent the import into the US of specific products originating in Xinjiang, China, where forced labour is presumed to occur.

Who?

The core purpose of the FLP Regulation is to prevent companies from importing, exporting or selling goods within the EU which have been made with forced labour (regardless of where in the supply chain the forced labour occurred). Unlike CS3D, the FLP Regulation applies broadly to all companies, including small and medium sized enterprises and foreign entities who engage in these activities.

The meaning of "products" is not restricted in the same way as the EU Deforestation Regulation and other sector specific regulations, but applies to any product that can be valued in money and can form the subject of a commercial transaction, whether a raw material or processed product. Goods which have already reached end users are expressly excluded.

When?

The FLP Regulation is still in the final stages of being approved by the European institutions. The European Council is expected to rubber stamp the version approved by the European Parliament in April, subject to minor linguistic finalisation.

Being a regulation rather than a directive, there is no need for the FLP Regulation to be enacted into national Member State laws. It will enter into force on the day following its publication in the EU's Official Journal, and will apply 3 years after its entry into force. Subject to publication occurring in 2024, the FLP Regulation will therefore apply from late 2027.

What?

Whilst CS3D imposes due diligence requirements with respect to human rights including labour standards and environmental matters, the FLP Regulation only focuses on forced labour. The meaning of forced labour is common to both laws, being based on Article 2 of the ILO Forced Labour Convention.

The FLP Regulation is somewhat unusual in its construction – it prohibits the import into the EU and the export from the EU of products manufactured with forced labour whilst not specifying any required actions on the part of importers or exporters. Member States' authorities will conduct risk-based investigations, but will first request certain information from the importer, including actions taken to prevent, mitigate, bring to an end or remediate risks of forced labour in their supply chain.

There is a clear statement in the FLP Regulation that it does not create additional due diligence obligations besides those already provided by Union or national law; the recitals reference the EU Regulation on Conflict Minerals, the Batteries Regulation, the EU Deforestation Regulation and CSRD (the latter is not commonly seen as imposing new due diligence requirements, in the sense that reporters would be free to disclose only a cursory process by which material impacts, risks and opportunities are identified). The definition of "due diligence" refers, however, to efforts by business to implement both mandatory and voluntary measures to identify forced labour.

Therefore in practice, it seems inevitable that importers will be required to do a degree of supply chain due diligence in respect of products not covered by those regulations in order to ensure that forced labour is not occurring, or run the risk of action being taken against them.

The FLP Regulation envisages that each Member State will designate one or more competent authorities who will have the responsibility of implementing the Regulation and carrying out any necessary investigations into suspected forced labour in the import/export of goods.

If products are found to have been made using forced labour, businesses will be prohibited from placing the products on the EU market or exporting or re-exporting them from the EU.

What risks are associated with failure to comply with supply chain diligence laws?

The new multi-pronged enforcement regime envisaged by these supply chain laws lies in contrast to existing related regimes, for example under the corporate reporting obligation of the UK's supply chain diligence legislation, the Modern Slavery Act 2015, which has been criticised for lacking enforcement "teeth".

Fines and civil liability

National authorities will be responsible for enforcement against companies who fail to comply with the CS3D. Their powers will include an ability to launch inspections and investigations and impose financial penalties for non-compliance. CS3D provides that the maximum level of financial penalties shall be not less than 5% of net worldwide turnover (of the group, where the infringing business is an ultimate parent company).

In addition, CS3D provides victims of a business's intentional or negligent failure to prevent or bring adverse impacts to an end with an avenue to pursue civil action for full compensation. Whilst the extent to which companies can be held liable under the civil regime will differ from Member State to Member State, the creation of this new cause of action is likely to lead to an increase in the number of claims for human rights and environmental violations, particularly given that Member States must also allow injured parties to authorise representatives, including trade unions and NGOs, to bring claims on their behalf.

Trade interruptions

Under the FLP Regulation, where Member State competent authorities find that products have entered the EU market or been exported in violation of the forced labour ban, these decisions will be communicated to customs authorities who will then use that information to identify further shipments that may not be compliant.

Under CS3D, Member States may take into account a tenderer's compliance with CS3D when awarding public contracts, which could be financially very significant for some businesses.

Reputational Damage

In addition to the fines described above, decisions in connection with penalties for infringements of CS3D implementing laws must be made publicly available for at least five years. This "transparency mechanism" (or naming and shaming approach) has the potential to cause significant damage to the reputation of companies concerned.

By contrast, the FLP Regulation does not directly envisage the "naming and shaming" of economic operators. The Commission will establish a database of forced labour risk areas or products, based on independent and verifiable information. It will not directly name economic operators, however it is foreseeable that NGOs and interested stakeholders will be able to reverse engineer the data in order to produce a short-list of businesses potentially trading in forced labour products. Even if not true, such accusations can be extremely damaging to businesses' reputations.

The interconnection between CSRD and the supply chain diligence laws should also be taken into account, given than CSRD requires a business to disclose its due diligence process. Any mismatch between the business's actions and the requirements of CS3D or other laws, to the extent a business is covered by both, will be exposed in CSRD.

Mitigating supply chain risk

- Understand your suppliers: At the core of both

regimes is a requirement to be responsible in the selection of

business partners, and to understand the nature of suppliers'

businesses, including any heightened risks. Key questions to

consider are the extent to which suppliers are supervised/audited

and where risks in supply chains lie, for example in relation to

industry or country-specific risks. Another important consideration

is how responsibility for the governance of suppliers is managed

(e.g. through shared policies or otherwise), as robust governance

processes can very often be a defence to claims whilst poor

governance invites them. Businesses should also review how

relationships with suppliers are defined, including ensuring that

contractual arrangements allow adequate access to information and

adjustment of the relationship should adverse impacts be

discovered.

- Evaluate your relationships: In higher risk

industries and geographies where ESG audits (such as social audits)

are commonplace, and given their increasing importance as a tool to

demonstrate adequate diligence, the question of how to remedy an

issue identified in the course of an audit is a complex one. As

noted, disengagement can have serious unintended consequences, and

both CS3D and the FLP Regulation recognise that it is not an

optimal solution. Rather than rush to terminate relationships,

organisations should work with advisors, including legal counsel,

at the outset of their supply chain evaluation to develop an

informed and considered crisis management plan.

- Consider your messaging: As companies come

under increasing ESG-related scrutiny, many have sought to revamp

(or introduce) ESG policies and frameworks, which can often involve

the release of public-facing statements regarding their

environmental and governance policies (including statements as to a

company's relationship with and management of its suppliers).

Such statements may subsequently be relied upon by investors and

customers, as well as the victims of alleged corporate wrongdoing

across an organisation's international supply chains. CS3D

contains prescriptive elements for policies and codes of conduct

which should all be carefully checked off but at the same time

calibrated with the organisation's overall approach to ESG and

stakeholder expectations. It has never been more important for

organisations to get their messaging right, and consider whether

what has been published accurately reflects the nature of

relationships with suppliers, as well as the scope of any broader

ESG commitments and other public statements.

- Engage senior leadership: Ensuring that top-level management are engaged and aware of the potential risks (and potentially opportunities) that these new regimes create will be critical to an organisation successfully navigating them. Given the scale and nature of the risks involved, supply chain legislation should in any event be a board-level issue. Clarifying the board's and senior management's role in overseeing sustainability governance processes will be key, including which internal committees will review and decide on sustainability matters, as well as the allocation of adequate resources and responsibility for disclosures.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.