This is my perspective: when I began organizing events for the Robotic Patent Drafting (RPD) community, I believed that people would buy RPD tools based on their features. That is why I included a detailed comparison table in my RPD Manifesto (click here to buy), listing all the then-available RPD tools and their respective features.

Later, I found out that while this is true, comparing Automated Patent Drafting Tools in this way is not correct.

I have since trained more than 50 patent attorneys in using RPD tools. What I discovered is that they care most about how the tools help them solve their problem: drafting better quality patent applications in less time. They do not care much about specific features as long as they achieve their goal.

Starting Question #1: What is the Available Input Data

This is what I found out to be the most crucial point for a demonstration: to determine what is the the typical starting point of a specific patent attorney before you explain how a robot works.

I found that the following 7 scenarios cover 99% of all possible cases out there:

Scenario 1: There is a written invention disclosure provided but it comes without claims and without any figures, and consequently, there are no reference signs. We have a text only.

Remark: I found out that RPD manufacturers rarely read patent law texts. That is why they often use different terms for the same thing. For example, some say "reference numbers." Others say "reference numerals," "labels," "reference characters," "numerical identifiers," "designators," or "markers." To be clear, the law uses the term "reference sign" (Rule 43(7) EPC and MPEP 1824, R-07.2015).

Scenario 2: Same as scenario 1 and in addition, there are figures, but they come without any reference signs.

Scenario 3: Same as scenario 1 and in addition, there are figures and they come with reference signs, sometimes both in the figures and in the invention disclosure, and sometimes only in the figures.

Scenario 4: There are patent claims provided but they come without any figures, and consequently, there are no reference signs.

Scenario 5: Same as scenario 4 and there are figures, and sometimes they come with reference signs, sometimes both in the figures and in the invention disclosure, and sometimes only in the figures.

Scenario 6: There are patent claims and they come with an invention disclosure. Sometimes they come with reference signs, sometimes both in the figures and in the invention disclosure, and sometimes only in the figures.

Scenario 7: There is an existing patent application and there is an add-on paragraph as an invention disclosure that often but not always comes with an add-on figure.

From my many trainings I know that the most common case is scenario 2, followed by scenario 5.

The other scenarios are less common, but they still exist. I remember once asking an RPD manufacturer to rewrite an existing patent so that the new patent encompassed the old one without repeating the original language. The RPD manufacturer did this, and you could hear a needle drop while they were doing it. The audience went silent because they realized how powerful such a tool can be if it falls into malicious hands.

Starting Question #2: What is The Expected Quality of the Patent

As a patent attorney, I take a pragmatic stance on patent quality: there is no bad patent application. If there is, it is likely a professional liability case.

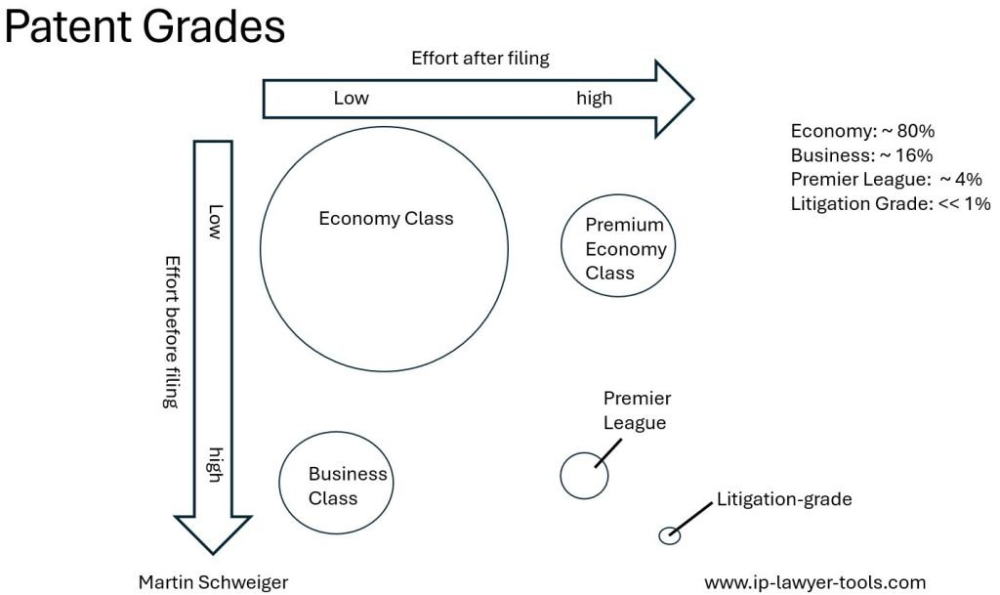

You can find patents where different levels of time and effort were invested. This can occur either before the filing date when drafting the patent application or after the filing date but before the grant of the patent, during the prosecution of the patent application. This results in four different classes of patent applications, which I call "Economy Class," "Business Class," "Premium Economy Class," and "Premier League."

The difference between a "Business Class" and a "Premium Economy Class" patent is significant. A lot of effort is put into a "Business Class" patent both before and after filing the application. In contrast, a "Premium Economy Class" patent often stems from an application with less effort before filing. The applicant then discovers its importance and invests more effort during prosecution. Seldom can a lack of effort before filing a patent application be compensated by more effort during prosecution. The resulting patent will differ from a "Premier League" patent.

There is one type of patent application that is very different from the "Economy Class," "Business Class," "Premium Economy Class," and "Premier League" categories: the "Litigation-grade Class" patent application. As a patent attorney, I can immediately recognize a "Litigation-grade Class" patent application. I first read about this concept in Craige Thompson's book "Patent Offense: 7 Steps to a Safe, Secure Patent Portfolio." You can find an interview with Craige on my website, here.

For a quick overview, my quality criteria are best shown in the following diagram:

It is important to note that about 80% of patents worldwide fall into the "Economy Class" grade, which includes "Premium Economy Class." The other 20% are "Business Class" or "Premier League," with much less than 1 in 100 being "Litigation Grade." I speak from experience, as my team and I have worked on more than 19,000 patent cases since 1996. I discovered this number when we switched from our old case management system to a new one a few years ago.

Starting Question #3: What is The Expected Language of the Patent

While most language models work best with English language, there are some that work in other languages, such as German or Chinese.

There are some work-arounds for other language by using translation bots. That starts with translating the input data into English, followed by providing a patent application draft in English language that is then translated back into the original language. This is not the preferred way, however. If a robotic patent drafting tool can work in a language that is different from English then this is a remarkable highlight that sould be demonstrated.

Other Starting Questions

All patent drafting tools are somewhat similar but they are also quite different from each other when it comes to details:

- what drafting style is required? US-style, EP-style, UK-style, CNIPA-style, or JPO-style, just to name a few. There is no patent drafting robot that supports all drafting styles.

- for what technology are you intending to draft a patent application? Some patent drafting handle some technical areas better than others.

And there are many more.

Sample Cases

I recommend to always use the same sample cases because this makes it easier to compare one patent drafting robot with another one.

In my workshops, I cover 4 technical areas. You may pick whichever you deem suitable to use for your own RPD product and download them accordingly.

Electronics Case:

- – Invention disclosure and claims with reference numbers (click here: Stromregelung mit mindestens einem Feldeffekttransistor with reference numerals 080523 )

- – Figures with reference numbers (click here: Stromregelung figures 080ß523 )

- – Invention disclosure and claims without reference numbers* (click here: Stromregelung mit mindestens einem Feldeffekttransistor without reference numerals 080523 )

Remark: The invention disclosure and the claims are in German language.

Software Case:

- – Invention disclosure (simplified) with reference numbers (click here: EXECUTION OF CONTAINERIZED PROCESSES WITHIN CONSTRAINTS OF AVAILABLE HOST NODES Invention disclosure 080523)

- – Figures (simplified) with reference numbers (click here: EXECUTION OF CONTAINERIZED PROCESSES WITHIN CONSTRAINTS OF AVAILABLE HOST NODES figures 080523)

- – Claims without reference numbers (click here: EXECUTION OF CONTAINERIZED PROCESSES WITHIN CONSTRAINTS OF AVAILABLE HOST NODES claims 080523)

Mechanical Case:

- – Invention disclosure with reference numbers (click here Citrus press invention disclosure with reference numbers 010523)

- – Invention disclosure without reference numbers (click here: Citrus press without reference numerals 010523)

- – Figures with reference numbers (click here: 2001_paperA_elec-mech_en)

- – Model solution (click here: 2001_paperA_elec-mech_ex-rep_en)

Chemistry Case

- Invention disclosure (click here: Invention Disclosure EP2484209 250124)

Explaining the Patent Drafting Robot Using a Video Demonstration

For 30 years, I have used the Youtube example of Tying A Shoelace Principle to illustrate the limitations of verbal instruction. It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to describe in written text the method of tying a shoelace in a way that 90% of readers could successfully implement it. However, this task can be easily taught to small children by their parents.

This example highlights an important point: some things cannot be effectively taught through words alone. There is an inherent weakness in teaching through books and articles.

To address this, the Youtube video mentioned above has three parts:

Part One, Introduction: The video begins with a humorous segment. This segment introduces the problem and engages the viewer's attention. You don't need that in the case of an automated patent drafting software. We patent attorneys know where the problem is: we want better patents in less time.

Part Two, Demonstration: The second part offers a "Gee whiz!" example. In this part, the demonstrator ties his shoelace in onöy one second. This impressive feat is meant to capture the viewer's interest and demonstrate the potential of the product. Note that this segment should not include a detailed explanation. The goal is to merely show the capability, and not how it is done.

Part Three, Instruction:

The final part of the video demonstrates the detailed process of tying a shoelace. This segment provides the step-by-step instructions necessary for the viewer to replicate the action. This instructional part provides clear, hands-on learning.

The ideal situation would be for the demonstrator to be physically present, guiding the viewer's hands. Audio, visual, and tactile elements combined offer the best learning experience. For robotic patent drafting, a remotely guided lessen by an experienced trainer is very helpful. I can say this because I have trained more than 50 people to draft patent applications with RPD tools.

By using this approach, you can effectively demonstrate the capabilities of your software product and provide clear instructions on its implementation. This method leverages the strengths of video to overcome the limitations of written text, offering a more engaging and comprehensive learning experience for your potential customers.

Example #1: The "Edge" Patent Drafting Robot

In the following, I have done a "Gee Whiz!" recording with Evan Zimmerman of the Edge company: www.withedge.com/

Evan started with the Electronics case: a German language invention disclosure, without patent claims but with a figure that comes with reference signs that he calls "labels". He altered the files that he downloaded from the links given above before he entered them into his RPD tool. This is equivalent to "scenario #3" above.

The input data is here

a) Invention disclosure: Stromregelung-mit-mindestens-einem-Feldeffekttransistor-without-reference-numerals-080523

(5)

b) Figures Stromregelung-figures-080s523

And here comes the video about using the Edge Patent Drafting Robot for that example:

And here are the three result files:

c) the patent application that was produced with the Edge patent drafting robot: Untitled_2024-06-29_02-36

d) the two figures: Figure 1 and Figure 2

Evan decided to provide an Economy Class patent application in English language, starting from a German language invention disclosure without claims but with figures that come with reference signs.

The result of the first recording was so good that he did not record the audio a second time and lay it over the existing video. He can in the future use the existing video either for explaining how the Edge robot works, without needing to click through the program. All what he needs is the start/stop button of the video player, and he can fully focus on what he says, talking in his own time.

Example #2: ChatGPT and the Qatent Patent Drafting Robot

I have done a short talk in front of German lawyers, and I wanted to produce a jaw-dropping experience for them.

So what I have done is to download an arbitrary circuit diagram from the Falstadt.com simulator and to convert it into a patent application, in less than 20 minutes time. I have then written an article about that, together with the video recording, here

What I wanted to demonstrate here was a novel feature of ChatGPT: to recognize a circuit diagram from an uploaded screenshot and to convert it into language, without having any further written description.

Step-by-Step Process for Recording a Good Demo Video for Your Own Robot

Step 1: Plan and Prepare Your Recording, Gather Tools and Software

- Obtain a professional video recording software like Camtasia. It is worth the learning curve.

- Set Up Your Recording Environment

- Ensure good audio quality by testing different microphones.

- Avoid using artificial backgrounds. Use a real backdrop like a bookshelf.

- Decide on the input data you will use (one of the seven standard cases above).

- Have all necessary other software ready (e.g., a tool for converting data and a word processor like MS Word).

Step 2: Record the Initial Video

Record yourself converting the input data into a patent application using the tool.

Do this in a straightforward manner, as you would do for yourself, without skipping any steps. Start from before loading the input data into your robot.

Perform the task slowly to ensure clarity, but aim to complete it in the shortest time possible.

It helps to have a human copilot who can ask questions if something is not clear or if you are advancing too fast.

Step 3: Edit the Video

After recording the session, utilize features of the recording software to enhance the video. For example:

- Highlight the cursor or enlarge sections of the screen when necessary to explain details

- Edit the recorded video to remove unnecessary parts.

- Accelerate monotonous sections (e.g., assigning reference numbers).

Ensure the video is concise and presents the process clearly.

Step 4 (optional): Record a Commentary Video

This step is only necessary if you have to cut out a lot or if you discover that your audio is not good.

I then recommend that you play the edited video again with the audio of the video switched off, while yourself providing commentary, and you record this. Warning: don't put your headshot into that video, use as much screen space as available for demonstrating your software.

You can use the pause and play buttons to start and stop the video as needed, providing detailed explanations when necessary while the video is paused.

In the final edit, you remove unwanted parts by cutting out parts of the commentary video that are unnecessary, such as pauses, filler words, or silences. Ensure the final video is neat and comprehensible, showcasing the entire process effectively.

A few Quality Measures

- Speak clearly and ensure that your commentaries are concise and informative

- Avoid background noise and maintain good audio quality

- Watch the entire video to ensure there are no mistakes and all steps are clear

Provide the viewer with the following files:

- The input data (often the invention disclosure and the figures)

- The raw data produced by the tool (often the patent application and the figures)

- The final edited patent application, after manually reworking it

Tips for Success

Focus on the process of drafting a patent application fast, and not on the features of the tools used.

Ensure good audio quality and a clean background.

Practice and seek feedback to improve your recording and editing skills.

Keep the video as concise as possible while covering all necessary steps.

Good success and see you soon in one of our workshops!

Martin "RPD" Schweiger

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.