The British Overseas Territories (such as The Cayman Islands) and the British Crown Dependencies traditionally have been jurisdictions fraudsters use to hide proceeds of crime. However, recent legislation on the Islands could make it easier to conduct investigations into fraud and white-collar crime.

fraud investigator obtains access to the bank statements of a company and discovers a wire transfer to another company in the Cayman Islands. The investigator knows the second company is located in a known tax haven and black hole when it comes to finding information about it. Has the investigation hit a dead end? No. The investigator has several options to identify who received the benefit of those monies.

Since I taught a breakout session on recovering illicit assets offshore at the 27th Annual ACFE Global Fraud Conference in 2016 (tinyurl.com/ycsrf437), I've seen several developments in offshore jurisdictions that will make investigating fraud and collecting information on corporate entities easier and more fruitful. However, it might also mean that those who aren't willing to be transparent are moving their operations to less-transparent jurisdictions.

For the purposes of this column, I make a distinction between the British Overseas Territories — which includes the Cayman Islands, The British Virgin Islands and Bermuda — and British Crown Dependencies — which include Guernsey, Jersey and the Isle of Man.

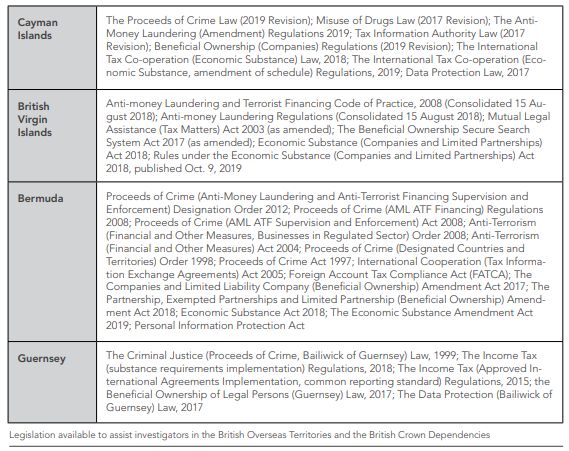

The table on page 13 contains the various relevant legislation in the British Overseas Territories and the British Crown Dependencies.

AML regulations

"The Islands" have had anti-money laundering legislation in place since the early 2000s. However, many offshore jurisdictions have amended that legislation since they've required local-service providers involved in financial transactions (banks, hedge funds, trustees, insurance companies, registered agents, lawyers, accountants and real estate agents) to be able to collect data on underlying beneficial owners and "politically exposed persons." Also, offshore banks are asking local-service providers for more information on cash turnover and expected sources of funds.

This collection of data should form part of your request when you seek a Norwich Pharmacal order (an order available in the U.K. and on the Islands for the disclosure of documents or information) from those offshore service providers given above.

Tax information disclosure

In recent years, the British Overseas Territories have established legislation (again, see the table on page 13) for localservice providers to collect and report tax information on their customers to government authorities on the Islands.

Each territory has its own website — for instance, the International Tax Authority is ditc.gov.ky. The legislation was initially focused on the U.S. Internal Revenue Service and U.S. tax avoidance and evasion. But in the last five years, the legislation has expanded to most of the 130 countries that participate in the Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (Each territory has its own website — for instance, the International Tax Authority is ditc.gov.ky. The legislation was initially focused on the U.S. Internal Revenue Service and U.S. tax avoidance and evasion. But in the last five years, the legislation has expanded to most of the 130 countries that participate in the Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (tinyurl.com/y86b5yej). The tax information that the banks and other financial service providers disclose to local government bodies isn't public, but if you obtain a Norwich Pharmacal order, this information should be in the banks' or financial service providers' files.

Public access to directors and beneficial owners

Many offshore jurisdictions that previously didn't allow public access to the names of directors and beneficial owners have either enacted legislation (or have committed to put such legislation into place) that provide greater access to such information. The Cayman Islands has enacted legislation that grants any person, for a fee of approximately US$61, the right to inspect a new list of names of directors of all companies and a separate list of names of managers of limited liability companies. These lists, which The Cayman Islands General Registrar (ciregistry.ky) maintains (rather than individual registered offices), differs from the register of directors and officers in that it only features names — not addresses — of current directors and alternate directors. And it doesn't include information about past directors. The public must review the lists in person at the registrar's offices. They're subject to conditions the registrar might impose. The British Overseas Territories have announced their intentions to introduce public registers of beneficial ownership (a natural person or persons who ultimately own or control a legal entity or arrangement, such as a company, a trust or a foundation) once the European Union countries, particularly countries like Luxembourg or Switzerland, establish their own public registers. The EU hasn't indicated whether it will cause its own countries to make such information public or provide timetables for doing so.

In the interim, service providers in the offshore jurisdictions are updating their current records. Some jurisdictions, such as The Cayman Islands, have new requirements that the register of members specify whether each class or category of shares (for example equity or preference) carries voting rights and, if so, whether such voting rights are conditional. The Cayman Islands' Registrar is required, after it receives written requests, to disclose to financial services regulators — plus anti-corruption, and other specific regulatory and policing bodies — any information it holds on companies that will enable these bodies to discharge their functions or exercise their powers under key regulatory and criminal legislation. These bodies are restricted on their use and disclosure of the registrar information.

Economic substance law

The Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, Guernsey and Jersey have legislation, as set out in the page 13 table, that requires certain entities — including holding companies, financing companies and those holding intellectual property — incorporated in those jurisdictions to have demonstrable economic substance., i.e., to be able to show they conduct activities on the Islands.

The laws in each of the Islands indicates those types of businesses the entities conduct that need to comply. Relevant entities that carry on activities in the offshore must satisfy economic substance tests as set out in the Islands' legislation. These can include evidence that the entities are conducting coreincome generating activities — for example, the provision of services for remuneration, which are appropriately directed and managed on the Islands.

Other evidence comprises:

- Adequate amounts of operating expenditure incurred on the Islands.

- A physical presence, including brickand-mortar places of business on the Islands.

- Having an adequate number of personnel on the Islands.

The legislation and guidance aren't tested yet. Many incorporated entities are entering into contracts with service providers to rent office space, retain accounting records, hold annual general meetings and carry out other local activities to address these new requirements. These requirements might provide other options for anti-fraud professionals who want to collect information on entities' operations and who controls their business affairs.

Is EU's GDPR a wrinkle?

The British Overseas Territories (except the British Virgin Islands) and the Crown Dependencies have also recently enacted local versions of the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in their respective jurisdictions, which incorporate the main components of the EU's version. These regulations consider data protection and privacy for all individual citizens and address transfer of personal information outside jurisdictions. GDPR aims primarily to give control to individuals over their personal data. The localized versions of GDPR means many service providers are reviewing personal information they've collected and delete data that they're either not required by law to collect or don't have individuals' consent to hold. This often includes personal data collected for marketing or promotional purposes.

The impact of this legislation is twofold: 1) It's likely that the personal information an entity has collected on customers is limited to just names, addresses and information collected for anti-money laundering and tax purposes, to comply with the laws in its jurisdiction. 2) Because GDPR is still developing, disclosure of personal information possibly will be an issue if the party seeking the data by court order isn't able to comfortably assure the courts or service providers that it will be able to protect the data. An interesting feature of the GDPR is that customers can ask entities what personal information it has on them. As an investigator, you might have a fraudster's cooperation and assistance in investigating an entity's transactions and affairs. Then you can ask the bank or service provider that the fraudster used to convert the proceeds of crime for the personal information it holds because it might unearth other useful information, such as the names of persons involved in introducing the business or another contact person for the account. At a minimum, it could affirm that the fraudster was a client with the institution.

Impact on investigating fraud and illicit activity

These developments in the legislation of offshore jurisdictions means there is, or will be in the future, further opportunities for collecting information and relevant documents in the investigation of fraud and illicit activity. However, I see an adverse consequence of the legislation. I've observed various entities in the British Overseas Territories — particularly holding companies — close as their owners and management consider other means to conceal (or at least impede availability of) the details of directors and beneficial owners. They might explain that rising costs forced them to shut down their businesses, but the reasons could be much more sinister.

Reprinted with permission from the July/August 2020 issue of Fraud Magazine, a publication of the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners in Austin, Texas ©20XX. However, authors wishing to reprint articles to use as promotional pieces or for other for-profit purposes must contact the Fraud Magazine Reprint Service at www.FraudMagazine.com.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

We operate a free-to-view policy, asking only that you register in order to read all of our content. Please login or register to view the rest of this article.