Corporate Whistleblower Awards Pilot Program ("Pilot Program"), aimed at incentivizing whistleblowers to report potential criminal conduct. The announcement was anticipated, having been previewed in March 2024 by Deputy Attorney General, ("DAG") Lisa Monaco, and yet its official launch offers potentially profound implications for companies and their compliance programs. It is the third initiative by DOJ in recent years to further incentivize companies and individuals to self‑report potential criminal conduct:

- In January 2023, DOJ revised the Criminal Division's Corporate Enforcement and Voluntary Self‑Disclosure Policy ("CEP") to, among other things, further incentivize companies to voluntarily self‑disclose "immediately upon the company becoming aware of the allegation of misconduct"; and

- In October 2023, DAG Monaco announced the M&A Safe Harbor Policy, intended to incentivize acquiring companies to promptly self‑disclose misconduct that they discover within an acquired entity, and to fully remediate such misconduct within a baseline period.

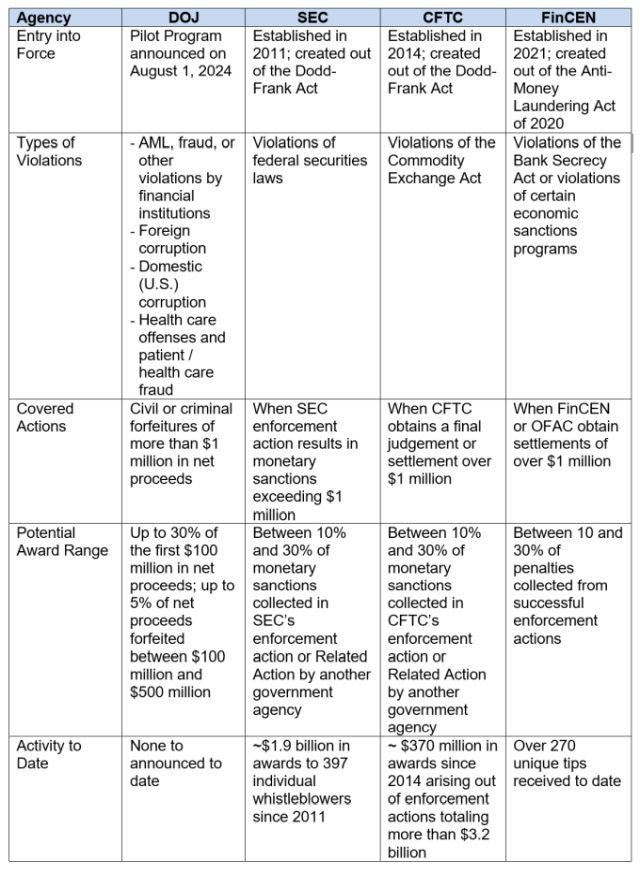

Now, with the Pilot Program, DOJ is aligning with other U.S. agencies, including the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC"), the U.S. Commodities and Futures Trading Commission ("CFTC"), and the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network ("FinCEN"), that have introduced whistleblower incentive programs to notable success.1 (see Annex A). Nonetheless, as arguably the most influential enforcement agency, particularly for offenses relating to international corruption, fraud, and money laundering, DOJ's Pilot Program has the potential to make lasting impacts across the evolving landscape of cross‑border investigations.

Whistleblower Pilot Program Elements:

The Pilot Program is open to individuals who provide (1) original, truthful information; (2) about criminal misconduct; (3) relating to one or more designated program areas; and (4) that leads to a forfeiture exceeding $1,000,000 in net proceeds. It excludes from eligibility a number of categories of persons, including those (i) who would be entitled to an award under another U.S. whistleblower program; (ii) DOJ employees and contractors, as well as their relatives and cohabitants; (iii) elected or appointed foreign government officials; (iv) those who "meaningfully participated" in the criminal activity being reported; and (v) those who make false, fictitious or fraudulent statements, withhold material or significant information, or otherwise interfere with the DOJ or its investigations.2

To qualify, the information provided must be considered as "original," meaning that it derives from the individual's (i) independent knowledge (i.e., was not derived from public sources); or (ii) independent analysis (i.e., was based on an examination of public information that reveals information not generally known or available to the public). The Pilot Program notes that even if DOJ has an ongoing related investigation, information could be considered as "original" if it was not previously known to DOJ and "materially adds" to the information already in DOJ's possession. Information will also be considered as "original" if it was reported internally and results in the company to which it was reported making a voluntary self‑disclosure to DOJ based on such information; although, the whistleblower must also report it to the DOJ within 120 days of the internal report.

Excluded from what is considered as "original" information are certain categories of information obtained (i) through communications subject to the attorney‑client privilege; (ii) as part of a legal representation; (iii) through an administrative or judicial hearing, or in a government report; (iv) due to the role of particular corporate officers, directors, partners, trustees, compliance officers, internal auditors, public accountants, or those hired to conduct internal investigations; and (v) through violations of law. There are, however, some notable exceptions to these exclusions, including for situations in which a disclosure is made to prevent criminal conduct "likely to harm national security, result in crimes of violence, result in imminent harm to patients in connection with health care, or cause imminent financial or physical harm to others...." In addition, if a report is made internally to a corporate officer, director, partner, trustee, compliance officer, or internal auditor, and more than 120 days have passed since such report was communicated to the audit committee, chief legal officer, chief compliance officer, or their supervisors, the individual to whom the report was initially made is entitled to disclose the information.

The Pilot Program is not universal in its coverage. Rather, it is intended to "fill gaps" in existing whistleblower reward programs and, as such, is limited to information relating to one of four areas where DOJ perceives a risk of criminal conduct going undetected:

- Violations – other than those already covered by the FinCEN whistleblower program – by financial institutions or their representatives of money‑laundering related offenses, registration of money transmitting businesses, fraud statutes, and fraud against financial regulators.

- Foreign corruption related offenses, other than those already covered by the SEC whistleblower program, including violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act or Foreign Extortion Prevention Act, and money laundering related offenses that do not involve issuers.

- Domestic (e., U.S.) corruption or kickback schemes involving federal, state, territorial, or local elected or appointed officials and government employees.

- Violations of health care offenses, other than those already covered by the Federal False Claims Act qui tam provisions, involving private or non‑public health care benefit programs and/or frauds against patients, investors, or non‑governmental entities in the health care industry.

The Pilot Program is designed to run for an initial period of three years, during which time DOJ may make and publish revisions to the Program. To be eligible, information must have been communicated to DOJ after the August 1, 2024 publication of the Program's details.

The potential recoveries, and, by design, financial incentives to make a report, are substantial. Eligible whistleblowers may receive up to 30% of the first $100 million in net proceeds obtained through a forfeiture action and up to 5% of any net proceeds forfeited between $100 million and $500 million. Assuming a whistleblower meets all of the eligibility criteria, and DOJ succeeds in obtaining $250 million in net proceeds through a forfeiture action, the whistleblower in this hypothetical would be entitled to $37,499,999.95. Even a more modest $5 million net forfeiture action by DOJ could result in qualifying whistleblowers receiving a potentially life‑changing $1.5 million in benefits.

Key Takeaways

While DOJ has long encouraged individuals to come forward with information relating to criminal conduct, the Pilot Program provides additional reason for companies to assess the systems that they have in place to receive and respond to whistleblower reports. It also has the potential to make a significant imprint on the manner in which companies conduct internal investigations in response to evidence or allegations of potential wrongdoing, including the calculus and timing of any potential self‑report they may consider making. Below are several key takeaways for companies to consider.

- Internal Reporting is not Required (but is Encouraged): The Pilot Program does not require individuals to first report allegations internally through a corporate whistleblower system before making a report to DOJ. It does, however, consider as a factor that could increase the amount of an award whether the whistleblower first made use of an internal corporate system. In such circumstances, whistleblowers must also submit the same information to DOJ within 120 days of reporting it internally to remain eligible for an award. The DOJ will also consider "whether the entity has adequate and available channels for internal reporting."

- As a result of the potential that individuals would miss out on a financial reward after a 120‑day period, companies should ensure that their whistleblower reporting systems are designed to promptly raise alerts to relevant internal resources, and that there are defined timelines established to respond to the whistleblower, conduct an investigation, and decide upon and implement any necessary remedial measures.

- Accelerated Self‑Disclosure Decisions: Companies may find themselves having to make more accelerated decisions regarding a potential voluntary self‑disclosure to DOJ following a whistleblower report. This derives from two timelines defined in the Pilot Program. First, as noted above, whistleblowers who make an internal report can still qualify under the Pilot Program if they also report to DOJ within 120 days of their internal report. Second, companies can still qualify for a presumed declination under DOJ's CEP if they (i) self‑report within 120 days of receiving the whistleblower's submission; and (ii) meet the other requirements under the CEP.

- When companies are faced with credible allegations of misconduct falling into one of the above areas, they will have to weigh within a relatively accelerated timeline of four months (i) the whistleblower's incentive to report to DOJ within 120 days so as not to miss out on a potential reward; and (ii) their own incentive to not miss out on a potential declination if they believe DOJ will be receiving a report from the whistleblower as well. In circumstances where allegations involve complex facts or require significant investigation and fact finding to assess their veracity, this may place companies in the uncomfortable position of having to consider a self‑report before a full and complete understanding of the gravity of a particular matter.

- Anticipate Whistleblower Forum Shopping: The approach that DOJ and other U.S. agencies are taking to offer financial incentives to whistleblowers stands in stark contrast to efforts in other countries to encourage more whistleblowing reports. In France, for example, legislators have passed laws in 2016 (loi Sapin II)3 and in 2022 (loi Waserman)4 to provide greater protections to whistleblowers and to require companies above a certain size to adopt and maintain independent and impartial whistleblower reporting systems, and to report back (within no more than 3 months) to whistleblowers on corrective actions taken or proposed to be taken.

- While whistleblower regulations in France also envision potential reporting externally to regulatory agencies, they explicitly define whistleblowers as those who make their report "sans contrepartie financiere" ("without financial compensation"). The EU Whistleblower Directive does not contain such limitations in how it defines who is considered as a "reporting person" entitled to protection, but nor does it specifically require implementing countries to offer financial incentives to whistleblowers. The fact that such incentives are traditionally not the case in Europe may prompt individuals working for European companies to chose to make a report to the U.S. on the hope of obtaining a reward even if facts would more naturally be dealt with in another jurisdiction.

Annex A: Existing Federal Whistleblower Reward Programs

Footnotes

1. In Fiscal Year 2023, for example, the SEC reported that it awarded nearly $600 million to 68 individual whistleblowers, including a single award of $279 million. The SEC also reported having received more than 18,000 tips in FY 2023, roughly a 50% increase from the prior year.

2. Also excluded are those individuals who acquire the reported information from a person who is otherwise excluded.

3. The loi Sapin II also required larger French companies to adopt and implement a compliance program with eight defined "pillars" to prevent and detect corruption or influence peddling. One such "pillar" includes an internal whistleblower alert line through which employees could report potential violations of the company's code of conduct.

4. The loi Waserman was adopted by France to implement EU Directive 2019/1937 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October, 2019 on the protection of persons who report breaches of Union law.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.