Article by Stefan Boettrick, MS*

In order for plaintiffs to certify a class in securities fraud class action litigation, they must demonstrate that class members relied on the allegedly fraudulent information. For cases involving publicly traded securities, one way plaintiffs can demonstrate reliance is to show that the securities at issue traded in an efficient market. Prices of securities that trade in an efficient market reflect all publicly available information and quickly respond to new information, and can thus be relied on to reflect relevant information about the security, including any information that was allegedly misrepresented. During the class certification stage of the litigation, plaintiffs may argue that the efficiency of the prices of a security can be used to provide an assumption of reliance for purchasers of the security. During the merits stage, efficient prices may be used to estimate alleged damages, as price movements form the basis for measuring the effect of particular events.

In securities litigation, the efficiency of the market for a security is routinely evaluated based on various criteria starting with those listed by the court in Cammer v. Bloom, known as the Cammer factors.1 These factors were listed by the court as indications of whether a market is efficient. This paper focuses on one specific Cammer factor, the existence of market makers and arbitrageurs in the market. In particular, an important issue to be addressed is whether traders are able to complete short sale transactions and thus fully participate in the market. A short sale enables a trader to take a negative position in a security, and is a crucial mechanism by which negative information can be rapidly reflected in market prices, but may be hindered by various constraints. Therefore, as part of Cammer factor analyses, indicators of constraints to short sales are valuable in evaluating claims of market efficiency.

A trader takes a negative, or short, position in a security by selling borrowed shares rather than owned shares. Borrowing shares requires finding a lender and negotiating a share loan, hurdles that can restrict trades from taking place. Consider, for example, a scenario in which a trader has a negative opinion of a stock he doesn't own. One way he may act on his beliefs is to short the stock by finding a lender, borrowing shares from him (possibly at a cost), and selling those shares in the open market, hoping to profit by buying shares back after the stock price has fallen. By short selling the stock, the trader's negative information becomes better reflected in market prices. Because this type of transaction is more complex than a typical share sale, complications may result in negative information not being quickly reflected in market prices. In turn, this may affect market efficiency. Consequentially, short sale constraints must be evaluated as part of an analysis of market efficiency.

Market Efficiency in Securities Litigation

In its seminal decision in Basic v. Levinson, the Supreme Court ruled that plaintiffs in 10b-5 litigation may claim a rebuttable presumption of reliance on the market price of securities traded on a "developed securities market, [where] the price of a company's stock is determined by the available material information regarding the company and its business."2 Investor reliance on market prices hinges on the definition of the Efficient Market Hypothesis, which states that prices in an efficient market reflect all publicly available information and quickly respond to new information.3 Thus, any alleged misstatements would also be reflected in the stock price. Plaintiffs, therefore, may claim reliance on alleged fraud through reliance on the "integrity of the market price" rather than demonstrating individual reliance on any misrepresentation.4

Although the Basic v. Levinson court did not mandate how to test for market efficiency, the later case of Cammer v. Bloom identified five factors that suggest a security traded in an efficient market: 5

1. The existence of an actively traded market for the security, as evidenced by a large weekly volume of trade,

2. That a significant number of securities analysts followed and reported on the security,

3. The existence of market makers and arbitrageurs who reacted swiftly to new information,

4. The eligibility of the underlying firm to file a SEC Form S-3 registration statement, and

5. Evidence of a cause and effect relationship between unexpected corporate events or financial releases and the security price.

Analyses of these factors form the basis for market efficiency analysis in securities class actions, and may be augmented with factors related to specific market attributes.6

The focus of this paper is on the third Cammer factor, the existence of market makers and arbitrageurs, and how their effectiveness may be affected by short sale constraints. Market makers facilitate trading and provide liquidity, while arbitrageurs swiftly transact in mispriced securities to ensure that prices always reflect available information.7 The Cammer court justified the importance of these participants in an efficient market since they "ensure completion of the market mechanism" by "react[ing] swiftly to company news and reported financial results by buying or selling stock and driving it to a changed price level."8 The value of these participants hinges on their ability to quickly buy or sell shares so that market prices always reflect all publicly available information. Arbitrageurs frequently react to negative information by shorting stock, while market makers frequently facilitate trades by short selling. If short selling is expensive or impossible, then completion of the market mechanism is impeded, which negatively affects market efficiency.

Short Sale Constraints and the Polymedica

Court

While affirming the Cammer factors as suggestive of market

efficiency, the Polymedica court took a step toward

defining market efficiency to be the "information

efficiency" of stock prices.9 The court concluded

that an "efficient market is one in which the market price of

the stock fully reflects all publicly available information,"

and defined "fully reflects" as instances when the

"market price responds so quickly to new information that

ordinary investors cannot make trading profits on the basis of such

information."10

In discussing the term "fully reflects," the Polymedica court emphasized that the speed of market adjustment to new information "depends on professional investors' ability to complete arbitrage transactions."11 Arbitrage was interpreted as the purchase or sale of a security until the market price reflects the new information or, as Polymedica's expert Dr. Frederick Dunbar put it, arbitrage is "the mechanism by which information becomes impounded in the stock price."12

Arbitrage promotes market efficiency through timely transactions by professional investors. If such investors trade on positive information, then their share purchases raise prices to the efficient level. Conversely, if such information is negative then professional investors who do not own shares must short-sell to lower prices to the efficient level. If professional investors are unable to quickly transact on their information, then market prices will not respond timely to new information or reflect all public information. In such a situation a stock is not efficiently priced.

The Polymedica court specifically highlighted the importance of short selling by arbitrageurs in an efficient market. It found that constraints on short selling could prevent a security's price from reflecting its informationally efficient value.13 Consequently, short sale constraints can slow the dissemination of information into the market which, by impeding quick price responses to new information, violates a key tenet of market efficiency.

Market Efficiency in Securities Markets

The market price of a security is the equilibrium value arrived at by market participants. Traders, using available information, buy and sell shares until equilibrium is reached. It is through this market mechanism that information is aggregated and reflected in a single price. Since market prices are a product of the information and beliefs of participating traders, the exclusion of classes of traders or types of trades systematically reduces the amount of information reflected in equilibrium prices.

According to the semi-strong version of the Efficient Market Hypothesis, efficient market prices reflect all publicly available information and quickly respond to new information, which ultimately depends on arbitrageurs reacting swiftly to new information. Arbitrageurs are motivated by profits generated by transacting in mispriced securities, which also provides them with an incentive to seek out pertinent new, and sometimes costly, information. It is a consequence of such research and trading that market prices are driven toward efficiency.

If such participants with unique relevant information do not trade, then the information they possess will not be reflected in market prices. An example of the importance of arbitrageur participation is the divergent market prices of Chinese domestic class A shares versus Chinese foreign class B shares in the 1990s. Despite both classes of shares having the same underlying rights and claims, researchers found that foreign class B traded at an average discount of about 60% to the domestic class A share prices.14 The researchers concluded that the main reason for this discrepancy was that domestic investors had more information about the local firms, but due to market segmentation could not participate in the market for foreign class B shares. While prices of each security reflected the information and beliefs of each market's participants, the exclusion of arbitrageurs from the foreign class B market resulted in mispricing.

Short Selling and Market Efficiency

Just as the exclusion of domestic traders from the market for

Chinese foreign class B shares resulted in mispricing, so can the

exclusion of short sellers from the market for a security. For

instance, in an efficient market, a short seller with solid

information that a stock trading at $10 was actually worth only $9

could borrow shares and arbitrage the price down to the $9 level.

In contrast, if there are constraints and it costs $1 to short sell

the stock, then it would not be profitable to arbitrage the price

to the efficient $9 value. The stock would thus not reflect all

available information and be inefficiently priced.

Short selling is an important tool of arbitrageurs, and excluding short sellers or restricting their trades can adversely affect how information is impounded into market prices. If the pool of traders able to transact in a security is limited to those who either own shares or have a positive opinion of the stock, then those who don't own it and have a negative opinion are excluded from the market. This limits the pool of traders able to trade on negative information to those who already own the stock. Furthermore, it reduces the incentive for non-owners to seek out information that may negatively affect the stock price because they are unable to trade.

Short Sale Bans and Market Efficiency

There have been some real-world consequences of constraints on

short sales. Constraints may be imposed by regulators, as most did

in response to the 2007-2009 financial crisis. The Securities and

Exchange Commission (SEC) was one such regulator, and on September

19, 2008 they issued an emergency order temporarily banning short

sales of certain stocks, with the objective of "restoring

equilibrium to [the] markets."15 While

acknowledging that "short selling contributes to price

efficiency," the SEC temporarily disallowed short selling in

799 stocks of financial institutions.16 The ban was

intended to stem aggressive short selling of financial stocks; such

firms were thought to be particularly susceptible to speculative

attacks on their credibility as institutions and counterparties.

Prior to the ban, it appeared that unfettered short selling had

contributed to "sudden price declines in the securities of

financial institutions unrelated to true price

valuation."17

In a 2013 study, Alessandro Beber and Marco Pagano found that short sale bans like the one instituted by the SEC had negative effects on factors associated with market efficiency.18 A main conclusion was that the lack of short sales slowed price discovery, the process through which market prices respond to new information. They found that price discovery in response to negative information was particularly hampered, insofar as "a ban moderate[d] the trading activity of informed traders who have negative information...and thereby slow[ed] down price discovery".19 According to the Cammer court, the specific role of market makers and arbitrageurs in an efficient market is to "react swiftly to company news and reported financial results by buying or selling stock and driving it to a changed price level." The empirical finding that the inability to short sell moderates trading and slows price discovery is a symptom of the breakdown of the role of the arbitrageur in completing the market mechanism.

Concretely, the researchers conclude that short sale bans "prevent bad news from being rapidly impounded into stock prices."20 Beyond the particular effects on arbitrageurs, such a finding runs contrary to generally accepted definition of an efficient market, also adopted by the Cammer and Basic courts, as "one which rapidly reflects new information in price."21

Beber and Pagano also found that banning short selling adversely affected market liquidity, which is the ability of the market to facilitate trading without greatly affecting prices. Although the Cammer court did not specifically identify liquidity as one of the five factors, it emphasizes that it is usually an important feature of a developed market.22

Short Sale Constraints and Market Efficiency

Constraints on short selling may occur for reasons other than

regulatory barriers. Given the mechanics of such a transaction, as

discussed in the next section, stocks may become short-sale

constrained simply because demand for loanable shares outstrips

supply. An interesting example of such an effect was documented by

Richard Thaler and Owen Lamont in a 2003 study.23 The

researchers found that due to constraints on short sales, market

prices violated a fundamental economic tenet: identical assets

should have identical prices. Their motivating example was the

spinoff of Palm from its parent company, 3Com.

On 2 March 2000, 3Com offered about 5% of its Palm subsidiary to the public via an initial public offering, and planned to issue the rest of the shares to 3Com shareholders by the end of the year. As part of the offering, holders of 3Com had the right to receive 1.525 shares of Palm stock for every share of 3Com that they owned. Given that conversion right, an investor could buy approximately 152 shares of Palm in two ways: either buy 152 shares of Palm in the open market or buy 100 shares of 3Com that, per the offering, included rights to about 152 shares of Palm. This simple conversion ratio implied that the price of 3Com should have been at least 1.525 times the price of Palm because each share of 3Com had rights to 1.525 shares of Palm. Immediately following the IPO, the closing market price of Palm was $95.06 per share, implying that, if arbitrageurs were able to trade, 3Com should have closed at least at $144.97.

Surprisingly, the price of 3Com actually fell on the IPO day to $81.81, much less than its implied value. If markets were operating smoothly, arbitrageurs could have paid $8,181.00 for 100 shares of 3Com and offset that position by receiving $14,449.12 from short selling 152 shares of Palm. Their net holdings of Palm would be about zero and they would have received $6,268.12 risk-free. The researchers pointed out that, despite the lucrative theoretical profits, such gains from this transaction were unlikely to be achievable because Palm was short-sale constrained. Due to the constraint, arbitrageurs could not engage in the above transaction. Short selling Palm stock was expensive or not possible, and the stock remained mispriced. This mispricing was not a short-term aberration; the researchers noted that it persisted for months on end despite widespread media coverage. Although this is an unusual situation, it brings up two important points regarding market efficiency:

1. Short sales are sometimes crucial to achieving efficient market prices, and

2. Short-sale constraints and related market inefficiency may persist for long periods of time.

The Mechanics of a Short Sale

The complex mechanics of short sale transactions are a primary factor behind the manifestation of related market inefficiencies. To provide intuition into how short sale constraints develop, and how to identify if a stock is constrained, it is helpful to understand the details of short sale transactions. A short sale is different than a typical stock sale. In a typical sale, a trader might sell shares from his account to a buyer at an agreed upon price, and some time afterwards the transaction is settled per the agreement (i.e., shares are exchanged for cash), and the traders go their separate ways. However, since a short sale involves selling shares borrowed from a third party, there are actually two transactions taking place: a share loan and a share sale, the former of which remains unresolved until the share loan is repaid in kind.

Short sellers borrow shares from lenders and to sell in the

open market.

The trade is typically settled (shares and cash are delivered

to the respective parties) within three settlement days.

One way to illustrate the mechanics of this type of transaction is by example. Consider the hypothetical firm Gleason Gears. To short shares of Gleason Gears, the short seller (the share borrower) typically arranges a share loan by finding a share lender.24 If a lender is located, a loan is negotiated between the short seller and the lender. Once negotiated, the short seller is able to sell the borrowed shares to a purchaser just like a regular sale. From the perspective of the purchaser, the transaction is like any other: the buyer receives shares of the stock in exchange for cash, and the transaction is completed.25 On the other hand, the short seller is indebted to the share lender and has an outstanding share loan until he repurchases and returns shares of Gleason Gears. This is known as covering the short position.

Locating Shares to Borrow and Naked Short

Selling

Shares sold short must be borrowed from an incumbent holder that

must be located. Unlike a centralized marketplace, such as the New

York Stock Exchange (NYSE) or a bond pit where traders aggregate,

there isn't currently a central location where traders get

together to borrow and lend shares.26 Despite the

important role of the share lending market, it is a relatively

decentralized and informal marketplace. While there have been

innovations over the years, the market was recently described as

"relatively opaque".27 In a 2004 publication,

Jeff Cohen and others even noted that the market was

"dominated by loans negotiated over the phone between

borrowers and lenders".28

Given share location constraints, short sellers usually borrow shares from large institutions and index funds. Such institutions lend out shares through programs with custodial banks that cater to short sellers and their brokers. Beyond these large lenders and structured programs, short sellers may also borrow from broker-dealers with extra share supplies, proprietary trading desks, and even retail margin accounts.29

Unsurprisingly, such a primitive market structure does not always facilitate seamless share location. In a 2002 paper, Darrell Duffie and his co-authors showed that in some cases the effect of share search frictions can be strong enough to push asset prices above the valuation of even the most optimistic investors.30 Recent empirical research also suggests that search costs represent significant barriers to short selling, and that the structure of the equity lending market generally benefits lenders, as the difficulty in finding shares gives them the ability to set higher fees.31

Naked Short Selling and Regulation SHO

Since shares can sometimes be difficult to borrow, some traders

have resorted to short selling without borrowing, or even locating

shares. Short selling without borrowing shares is known as

naked short selling. Naked short selling has been

identified by regulators, CEOs, and many private investors as a

source of market instability and even potential manipulation. For

instance, in the early days of the 2008 financial crisis the bond

insurer MBIA complained to Congress about unfair speculation,

claiming that "self-interested parties have gone to

substantial effort to undermine the market confidence that is

critical to MBIA's business."32 Corporations

like MBIA, and a chorus of others, have complained to regulators

about abusive short selling, and have had some success in curbing

it.

The response by US regulators to abusive short selling has been measured and incremental. One of the first federal regulations was the SEC's adoption of Regulation SHO that became effective on 5 January 2005.33 Among other rules, Regulation SHO has a share "locate" requirement that prohibits broker-dealers from short selling without borrowing or arranging to borrow securities, or have reasonable grounds to believe that securities can be borrowed.34 Due to concerns about shocks to the market mechanism, market makers, and specialists in stock markets are exempt from the share location requirement.35 Options market makers were initially exempt, but became subject to share location requirements as part of emergency regulations adopted in September 2008.

Pricing a Share Loan and the Rebate Rate

Once a short seller identifies a suitable lender, they negotiate a

share loan. To secure the share loan, the borrower pledges

collateral, usually equal to 102% of the value of the shares. The

collateral is almost always cash, but may be Treasury

securities.36 The collateral is invested by the share

lender and generates interest. The share borrowing fee is reflected

in how much of that interest is given back to the share borrower,

and is expressed in a rate known as the rebate

rate.37 The more expensive a stock is to borrow,

the more interest is kept by the share lender and the lower the

rebate rate. In most share loans the rebate rate is close to what

is known as the general collateral rate.38 The

general collateral rate is approximately equal to standard

overnight lending rates, like the well-known Federal Funds

Effective Rate.39 If the rebate rate is close to the

general collateral rate then short sellers are rebated interest at

about the same rate as they would receive by lending the collateral

out themselves, which implies that the cost to borrow shares is

close to zero.

On the other hand, if shares being lent out are in short supply or the market for equity lending is otherwise impaired, then the rebate rate may be less than the general collateral rate.40 The rebate rate can even be negative, requiring the short seller to pay fees above and beyond the interest accrued on the collateral. Securities for which the rebate rate is below the general collateral rate are defined as being on special with the difference between the rates known as the specialness.41

The rebate rate on shares can change on a daily basis depending on supply and demand, just like the price of a stock. This presents an added risk to short sellers, as the rebate rate on their collateral may change over the course of their share loan. The value of a share loan is also marked to market on a daily basis; changes in the price of the underlying stock affects the value of the share loan and the amount of collateral required.42

Selling Borrowed Shares and Delivery

Failure

Generally, once a lender is found and a share loan negotiated, the

short seller sells the borrowed shares to a willing buyer in the

open market. Once the transaction is executed, regulations require

delivery of shares to the buyer over the following three trading

days.43 Assuming there is an ample supply of loanable

shares, the transacted shares are usually delivered to the buyer

within that time, barring possible technical issues unrelated to

short selling.44 If, on the other hand, loanable shares

are hard to find or are in short supply, then share delivery may

not occur by the end of the third day. In that case a delivery

failure on the shares is triggered until the short seller

delivers shares to the buyer.

Aside from incidental technical issues, delivery failure is a direct consequence of naked short selling. While delivery failure doesn't tend to affect the purchasers' capital gains, losses, or dividend payments on the transacted shares, unsettled trades can affect corporate governance, investor confidence, and the viability of the trading mechanism.45

Persistent Delivery Failure and Regulation SHO

SEC Regulation SHO specifically addresses the issue of persistent

delivery failures, which are longer lasting fails and symptomatic

of structural market issues. Regulation requires designation of

securities with persistent fails (above a specified number of

shares and for five consecutive settlement days) as threshold

securities, and targets them with additional

rules.46 For instance, equity market makers with

outstanding delivery failures may no longer rely on the bona-fide

market making exception in effecting short sales.47

Threshold securities are also subject to what is known as a

close-out requirement. This requires broker-dealers to

close out any failure to deliver that has persisted for 10

settlement days by buying shares to satisfy

delivery.48

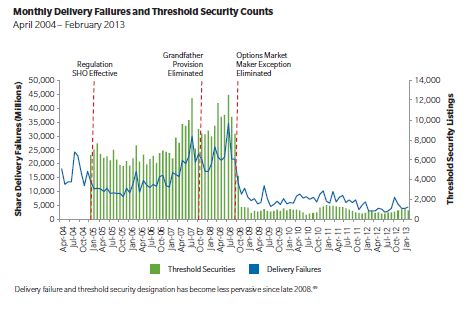

Monthly Delivery Failures and Threshold Security Counts

Initially, there were two exceptions to the close-out requirement. The first exception, called the "grandfather" provision, exempted fails to deliver on trades that occurred before the stock became a threshold security from close-out.50 For example, if a security was designated a threshold security on Wednesday, then shares that failed to be delivered the Tuesday before would not be subject to close-out. The second exception, called the "options market maker exception," exempted options market makers from the close-out requirement if their delivery fails arose from hedging options positions created before the stock became a threshold security.51

The "grandfather" provision was eliminated on 15 October 2007, while the "options market maker exception" was eliminated on 17 September 2008.52 Delivery failures and threshold security designations have become much less widespread since late 2008, as illustrated above. The timing of the drop-in delivery failures and threshold security designations corresponded with the elimination of the options market maker exception and implementation of other regulation as part of the September 2008 emergency order.53

Footnotes

* Consultant, NERA Economic Consulting. I thank David Tabak and Alan Cox for helpful comments and discussion, and Stephanie Plancich for reviewing earlier drafts.

1 Cammer v. Bloom, 711 F. Supp. 1264 (D.N.J. 1989).

2 Basic Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224 (1988), citing Peil v. Speiser, 806 F.2d 1154, 1160-1161 (CA3 1986).

3 See Eugene Fama, "Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work," Journal of Finance, Vol. 25, No. 2, May 1970, and Eugene Fama, Richard Roll, and Michael Jensen, "The Adjustment of Stock Prices to New information," International Economic Review, Vol. 10, Issue 1, February 1969. Market prices that reflect all publicly available information (known to all market participants) are known to be semistrong-form efficient. For a definition of semistrong-form efficiency see Investopedia US, http://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/semistrongform.asp.

4 Basic Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224 (1988).

5 For details of each factor see Cammer v. Bloom, 711 F. Supp. 1264 (D.N.J. 1989). A SEC Form S-3 is a simplified registration statement that may be used by companies that have met particular reporting requirements.

6 Other potentially relevant factors include the bid-ask spread, which is the difference between the bid and ask prices of the security, whether returns are predictable, and the market capitalization of the security.

7 The most common definition of arbitrage is "[a]n operation involving simultaneous purchase and sale of an asset" (see The MIT Dictionary of Modern Economics, 4th Edition, The MIT Press, 1992.) The Polymedica court cited the definition of arbitrage as "[t]rading on truly superior information," as a common definition, such that "the trader arbitrages between time periods, rather than between markets." (Lynn A. Stout, "Why the Law Hates Speculators: Regulation and Private Ordering in the Market For OTC Derivatives," Duke Law Journal, Vol. 48, 1999.) For details, see footnote 11 of In re PolyMedica Corporation Securities Litigation, 453 F.Supp.2d 260 D.Mass., September 28, 2006. The Cammer court also implicitly points to the latter definition, as it indicates that arbitrageurs "react swiftly to company news and reported financial results", which doesn't necessarily involve simultaneous asset purchases and sales.

8 See ¶21, Cammer v. Bloom, 711 F. Supp. 1264 (D.N.J. 1989).

9 In re PolyMedica Corporation Securities Litigation, 453 F.Supp.2d 260 D.Mass., September 28, 2006.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Sugato Chakravarty, Asani Sarkar, and Lifan Wu, "Information Asymmetry, Market Segmentation and the Pricing of Cross-Listed Shares: Theory and Evidence From Chinese A and B Shares," Federal Reserve Bank of New York, No. 9820, 1998.

15 "SEC Halts Short Selling of Financial Stocks to Protect Investors and Markets", SEC News Release, 2008-211.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Alessandro Beber and Marco Pagano, "Short-Selling Bans Around the World: Evidence from the 2007–09 Crisis," Journal of Finance, Vol. 68, Issue 1, Feb. 2013.

19 Ibid, p. 347.

20 Ibid, p.347.

21 Cammer v. Bloom, 711 F. Supp. 1264 (D.N.J. 1989).

22 See Cammer v. Bloom, 711 F. Supp. 1264 (D.N.J. 1989), citing Alan A. Bromberg and Lewis D. Lowenfels, Securities Fraud & Commodities Fraud §8.6 (1988), (A developed market "is principally a secondary market in outstanding securities. It usually, but not necessarily, has continuity and liquidity (the ability to absorb a reasonable amount of trading with relatively small price changes).").

23 Owen A. Lamont and Richard H. Thaler, "Can the Market Add and Subtract? Mispricing in Tech Stock Carve-Outs," Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 111, No. 2, 2003.

24 Broker-dealers are required to either locate securities or have reasonable grounds to believe that securities can be borrowed prior to short selling. Equity market makers engaged in bona-fide market making activities are exempted from this rule.

25 This assumes that the shares are actually "delivered" upon settlement from the short seller to the purchaser, a fine point of the transaction that is discussed below.

26 From 1926 to 1933 there was a centralized stock loan market on the floor of the NYSE known as the "loan crowd". For details of the operation of this market see Charles M. Jones and Owen A. Lamont, "Short-Sale Constraints and Stock Returns," Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 66, No. 2, 2002.

27 See Adam C. Kolasinski, Adam V. Reed, and Matthew C. Ringgenberg, "A Multiple Lender Approach to Understanding Supply and Search in the Equity Lending Market," Journal of Finance, Vol. 68, Is. 2, April 2013.

28 Jeff Cohen, David Haushalter, and Adam V. Reed "Mechanics of the Equity Lending Market," published in Short Selling: Strategies, Risks, and Rewards, Wiley, 2004.

29 Gene D'Avolio, "The Market for Borrowing Stock," Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 66, No. 2, 2002.

30 Darrell Duffie, Nicolae Garleanu, and Lasse Heje Pedersen, "Securities Lending, Shorting, and Pricing," Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 66, No. 2, 2002.

31 See Adam C. Kolasinski, Adam V. Reed, and Matthew C. Ringgenberg, "A Multiple Lender Approach to Understanding Supply and Search in the Equity Lending Market," Journal of Finance, Vol. 68, Is. 2, April 2013.

32 "Nasty, brutish and short," The Economist, June 19, 2008.

33 See SEC Release No. 34-50103, July 28, 2004. Prior to Regulation SHO, similar rules were published by self-regulatory organizations (SROs), such as NASD Rule 3370 (See http://www.sec.gov/pdf/nasd1/3000ser.pdf) and NYSE Rule 440C (See http://www.nyse.com/nysenotices/nyse/rule-interpretations/pdf?number=197).

34 The SEC generally refers to these borrowing procedures as share "locate" requirements.

35 Exemptions are discussed below. For additional details see http://www.sec.gov/spotlight/shortsales.shtml.36 See p. 275 of Gene D'Avolio, "The Market for Borrowing Stock," Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 66, No. 2, 2002. Also see p. 247 of Christopher C. Geczy, David K. Musto, and Adam V. Reed, "Stocks are Special Too: An Analysis of the Equity Lending Market," Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 66, No. 2, 2002.

37 The rebate rate is expressed as an annualized percentage of the value of the securities under loan.

38 The "general collateral" interest rate is a term borrowed from the bond repo market and is the rate applied when the underlying asset (in this case, loaned shares) are not in particular demand. Researchers, such as Geczy et al. have found these rates to be close to overnight lending rates. See Christopher C. Geczy, David K. Musto, and Adam V. Reed, "Stocks are Special Too: An Analysis of the Equity Lending Market," Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 66, No. 2, 2002.

39 Christopher Geczy and others analyzed rebate rates of share loans and found that large and medium sized share loans typically had rebate rates between 8 and 15 basis points below the Federal Funds Effective Rate. For details see p. 247 of Christopher C. Geczy, David K. Musto, and Adam V. Reed, "Stocks are Special Too: An Analysis of the Equity Lending Market," Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 66, No. 2, 2002.

40 Beyond the total supply of loanable shares, researchers have also found that rebate rates are lower (i.e., borrowing costs are higher) if lenders are difficult to find or don't have to compete with each other. See Adam C. Kolasinski, Adam V. Reed, and Matthew C. Ringgenberg, "A Multiple Lender Approach to Understanding Supply and Search in the Equity Lending Market," Journal of Finance, Vol. 68, Is. 2, April 2013.

41 See p. 246 of Christopher C. Geczy, David K. Musto, and Adam V. Reed, "Stocks are Special Too: An Analysis of the Equity Lending Market," Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 66, No. 2, 2002. I also use the term specialness rate to refer to the specialness of the security.

42 Jeff Cohen, David Haushalter, and Adam V. Reed "Mechanics of the Equity Lending Market," published in Short Selling: Strategies, Risks, and Rewards, Wiley, 2004.

43 Regulations stipulate that equity trades settle within three settlement days after the transaction date. For details see http://www.sec.gov/investor/pubs/tplus3.htm. Shares not delivered within this period trigger a delivery failure, which broker-dealers may not systematically engage in unless they are exempt.

44 See SEC Release No. 34-56212, August 7, 2007. ("There may be many reasons for a fail to deliver. For example, human or mechanical errors or processing delays can result from transferring securities in physical certificate rather than book-entry form, thus causing a failure to deliver on a long sale within the normal three-day settlement period.")

45 See John D. Finnerty, "Short Selling, Death Spiral Convertibles, and the Profitability of Stock Manipulation," Working Paper, Fordham University, 2005.

46 See SEC Release No. 34-50103, July 28, 2004. To be designated a threshold security, the number of aggregate fails to deliver at a registered clearing agency must exceed 10,000 shares or more per security and the level of fails must equal to at least one-half of 1% of the issuer's total shares outstanding.

47 Ibid, see section B(2), Close-out Requirement.

48 Ibid.

49 The number of fails to deliver is the aggregate balance level outstanding recorded on the National Securities Clearing Corporation's Continuous Net Settlement (CNS) system. This includes all NYSE, NASDAQ, AMEX, and OTCBB securities, per the definition of CNS, available at http://www.dtcc.com/downloads/products/learning/Settlement.pdf. Share delivery fails are in shares per day, so shares not delivered for multiple days would be counted as multiple failures. For details see http://www.sec.gov/foia/docs/failsdata.htm. Threshold security listings are the total number of securities designated on a daily basis as such by the NYSE, NASDAQ, and AMEX. OTCBB securities are not included in the threshold security counts.

50 See SEC Release No. 34-50103, July 28, 2004.

51 Ibid.

52 For details on elimination of the "grandfather" provision, see SEC Release No. 34-56212, dated August 7, 2007. For details on elimination of the "options market maker exception" see SEC Release No. 34-58572 dated September 17, 2008, and SEC Release No. 34-58775 dated October 14, 2008. Elimination of the options market maker exception coincided with implementation of Regulation SHO Rule 204T, which imposed "a penalty on any participant of a registered clearing agency, and any broker-dealer from which it receives trades for clearance and settlement, for having a fail to deliver position at a registered clearing agency in any equity security." The relevant provisions of this rule were made permanent in July 2009. For details of Rule 204 see SEC Release No. 34-58572 dated September 17, 2008 and SEC Release No. 34-60388 dated July 27, 2009.

53 See SEC Release No. 34-58572 dated September 17, 2008.

To read the rest of this article and footnotes in full please click here

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.