Artificial intelligence (AI) has rapidly transformed many aspects of everyday life, including the legal profession. IP practitioners have had to rapidly adapt because of the numerous questions raised by AI in the IP realm. The United States Copyright Office (USCO) and the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) are continuing to solicit feedback to determine how IP law should handle AI.

The USCO is currently drafting new guidance on a gambit of AI-related copyright issues, such as the fairness of using copyrighted works for AI training and what exclusive rights AI systems can violate.1This guidance is expected to be released later this year. So far, the USCO has released initial guidance on the copyrightability works that utilize AI. The USCO divides these works into two groups: AI-generated works and AI-assisted works.

AI-generated works are those where traditional creative expression were produced exclusively by a machine, such as an AI. These works are not eligible for copyright protection because they do not have a human author. For example, the USCO has said that a work generated by an AI after receiving a human-entered prompt is not copyrightable because the human exercised limited "creative control" over the artistic process.2

AI-assisted works are works that have been altered by a human so extensively that the final work constitutes human authorship. These modifications can vary from the mere arrangement of AI-generated works to material alterations of an AI-generated work. However, only the human modifications are copyrightable; the underlying AI-generated work alone is not protectable and must be disclaimed.

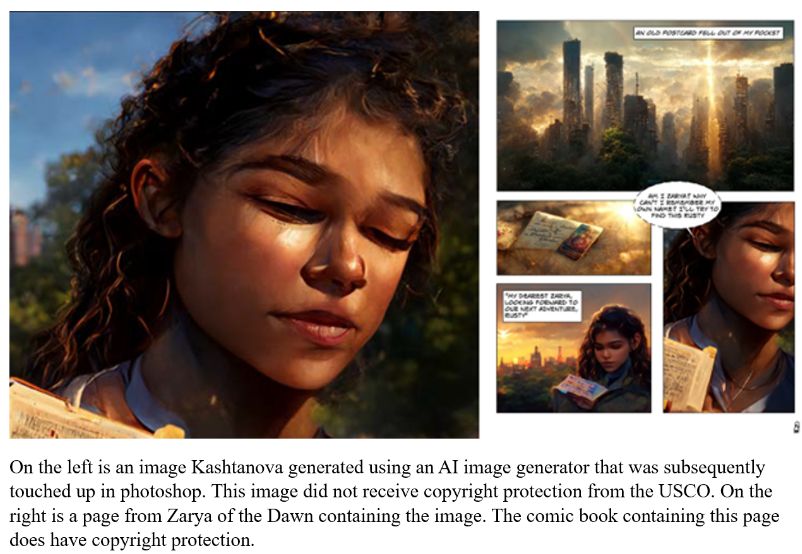

For example, the USCO had initially registered a comic book entitledZarya of the Dawn. The USCO eventually discovered that the work was created with the assistance of AI. The author, Kristina Kashtanova, used AI to generate the pictures in the comic book but wrote the book's story herself.

The USCO reissued the comic book's registration, cancelling protection for the AI-generated images and only protecting the expression created by Kashtanova — the written story and the "selection, coordination, and arrangement" of the comic book — and cancelled protection for the AI-generated images.3

The USCO has announced a similar policy for works already registered that did not initially disclose the assistance of AI. Any work registered that failed to initially disclose the use of AI can be corrected through a supplementary registration. The author can disclaim the AI-generated portions of the work and retain protection for the human-created expression through this supplemental registration.4

Human expression has long been the sole form of expression protected by copyright law. In 1884, the Supreme Court found inBurrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Saronythat authors are "he to whom anything owes its origin; originator; maker; one who completes a work of science or literature."5

Under the modern Copyright Act, protection is afforded to "original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression."6While the statute does not define who or what qualifies as an author, the Ninth Circuit inNaruto v. Slaterfound that because the Copyright Act refers to an author's children and grandchildren; the legitimacy of the author's children; and the author's widow, human authorship is implied.7

Most recently, the D.C. District Court inThaler v. Perlmutterreviewed the USCO's decision to not registerA Recent Entrance to Paradise, a painting made entirely by an AI. Affirming the USCO's decision, the court stated that "[h]uman authorship is a bedrock requirement of copyright."8

The USCO's decision to protect the larger work ofZarya of the Dawnhighlights another statutory basis for protecting AI-generated works: compilations. Under17 U.S.C § 101, a compilation of "pre-existing material, facts, or data" is nevertheless copyrightable if the "selection, coordination, and arrangement" of the uncopyrightable elements is original.9

While AI-generated works themselves are not copyrightable, a larger work comprising AI-generated elements is protectable if the overall work meets the minimum level of creativity required for copyright protection. Compilations currently provide the best avenue for protecting AI-assisted works.

While the USPTO has not yet released guidance on how AI systems can be evaluated for subject-matter eligibility, obviousness, or enablement, the USPTO recently released guidance for AI inventorship. The USPTO made three major announcements: inventors and joint inventors must be humans; inventions created with the assistance of AI are not categorically unpatentable; and how AI impacts practicing before the USPTO.10

First, the USPTO followed the Federal Circuit's decision inThaler v. Vidal, confirming that only natural persons are eligible to be inventors.1135 U.S.C. § 100(f)-(g)only permits individuals to be inventors or coinventors.

Relying on this definition, the Federal Circuit inThalerapplied Supreme Court precedent, which found the term "individual" means human being unless indicated otherwise, and held that only humans can be inventors.

Announcing that AI systems cannot be inventors is certainly not new. In 1993, the Federal Circuit inBeech Aircraft Corp v. EDO Corp.stated corporations could not be inventors. Instead, only "natural persons" are eligible to be inventors.12However, the clear statement by the USPTO in support of the Federal Circuit's position leaves no room for ambiguity: AI systems cannot be inventors.

The USPTO next clarified that AI-assisted inventions can be patentable because the core of an invention is the conception — "a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention."13If a human inventor conceives of the invention, even with the assistance of an AI system, then the invention is patentable.

The USPTO's guidance clarifies that AI-assisted inventions must have at least one human inventor who made a "significant contribution" to the claimed invention under thePannu v. Iolab Corp.factors and that each claim must have at least one human inventor.14

The USPTO specifically highlighted the firstPannufactor, that the inventor "contribute[d] in some significant manner to the conception or reduction to practice of the invention," by noting it requires the inventor to understand and value the invention at the time of its creation.

And merely reducing an AI-conceived invention to practice, like all inventions, does not satisfy this first factor. There must therefore always be at least one human who significantly assisted in the invention's conception and the claims must only reflect the portion of the invention conceived by human inventors.

WhilePannuinterpreted the joint inventorship requirements of35 U.S.C. § 116(a)between human coinventors, the USPTO has expandedPannu's applicability. AI systems can conceive of inventions; however, these conceived inventions are not eligible for patent protection because they were not conceived by a human.

The USPTO's announced position is that any time an AI system is used during the inventive process, the human inventor(s) must treat the AI system like a joint inventor and show that the human inventor(s) made a significant contribution to conception under the firstPannufactor. By applying thePannufactors this way, the USPTO is ensuring that only inventions that are significantly contributed to and therefore conceived by humans are protected instead of inventions conceived solely by an AI.

The recent guidance provides three examples of AI-assisted inventions with significant human contributions for inventorship purposes and four examples of insignificant contributions. While prompting an AI system with generalized research plans is not significant, the USPTO announced that constructing a detailed prompt with a specific problem in mind to get a particularized solution from an AI system can be significant.

Similarly, while reducing an AI invention to practice is not a significant contribution, modifying the output of an AI system or conducting experiments using the output can be a significant contribution.

Most importantly, the USPTO stated that a human who creates a building block for a larger AI-conceived invention does significantly contribute if the AI system was designed and trained to solve a specific problem using the human-conceived building block.

The USPTO also clarified that "maintaining 'intellectual domain'" over an AI system does not constitute a significant contribution to any inventions conceived by the AI system because the focus of inventorship is conception. Instead, such inventions are AI-generated and not eligible for patent protection.

Finally, the USPTO clarified changes and requirements for practice before the USPTO regarding AI-assisted inventions. The USPTO did not change the duty of disclosure but emphasized that information related to AI-inventorship that shows an inventor did not make a significant contribution must be disclosed.

Similarly, the duty of reasonable inquiry was not updated, but the USPTO underscored that practitioners must inquire about inventorship information, including whether and how AI was used in the inventive process. And once practitioners become aware of information affecting inventorship of an application, they must timely correct the application's inventorship according to37 C.F.R. 1.48(a), just like for any other inventorship issue.

If an examiner has a reasonable basis to believe that the disclosed inventorship information is incorrect, such as if the named inventor(s) did not make significant contributions to the AI-assisted invention, the examiner may request reasonably necessary information to determine the proper inventorship.

Arguably the most important announcement from the recent guidance is that a domestic application cannot claim priority to a foreign application that names an AI system as the sole inventor. The USPTO based this decision on35 U.S.C. §§ 119,120,121,365, and386and37 C.F.R. 1.78, which state that applications can only claim priority to applications that name at least one common inventor or joint inventor.

This guidance from the USCO and USPTO, while limited in scope, is helpful for resolving the most immediate issues generated by AI systems: whether AI systems can create copyrightable works and patentable inventions.Based on these guidelines, there are several things authors, inventors, and practitioners can do to protect their works and inventions.

For authors and inventors, the most important way to protect works and inventions is to document how they were made. For example, the Beijing Internet Court inLi v. Liugranted copyright protection to an image generated using over 150 prompt commands because the totality of commands used indicated sufficient originality for authorship.15

While the USCO stated in their guidance that works created by AI systems from a prompt are not copyrightable because of the lack of creative control held by the human entering the prompt, the court inLiignored the random nature of generative AI systems and instead found that the specificity of the prompts showed copyrightable human expression. The author's logs and prompts used were essential to the court's ruling.

To provide avenues for future protection in the US, authors and inventors should record the prompts used in AI systems when engaging in creative sessions.

Similarly, authors and inventors should record the resulting work or idea produced by the AI system. Both the USCO and USPTO made clear that AI-assisted inventions can be protected if a human alters the system's output with sufficient human creativity or conception.

By keeping a copy of the AI-generated work or idea, authors and inventors can contrast their final work or invention with the output of the AI system to emphasize the human-created expressions and inventions and protect their work.

There are also several takeaways for practitioners seeking to protect their clients' works and inventions. First, practitioners should request that their clients document any creative sessions that use AI systems as previously described.

The best way to protect your client's IP is to have facts to support any argument about its protectability. Having the evidence described above can be useful to craft stronger arguments about originality and conception than otherwise possible.

Next, practitioners should ensure that they submit any relevant information to the USCO and USPTO about AI-assisted works and inventions to avoid claiming unprotectable subject matter. Practitioners should strive to disclose this information early during the registration process to avoid later issues.

If information is not immediately available to a practitioner, they should amend their disclosures to the USCO or USPTO as soon as possible, either with a supplementary registration to disclaim AI-generated content at the USCO or by filing an updated information disclosure statement with the USPTO to clarify what aspects on the invention are human-conceived.

International patent practitioners should also ensure that any AI-assisted patent application lists a human as a co-inventor if filing outside the United States first. Some jurisdictions, such as South Africa, have permitted AI systems to be listed as sole inventors on patent applications.

However, the USPTO's guidance makes clear that if there is not a human inventor on the application that is being used to claim priority, then the priority claim will be rejected in the US. Therefore, having a human co-inventor on any foreign-filed applications is crucial for preserving priority.

Footnotes

1 Artificial Intelligence and Copyright, 88 Fed. Reg. 59942, 59946, 59948 (Aug. 30, 2023),https://bit.ly/3VXufei.

2 Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence, 88 Fed. Reg. 16190, 16192 (Mar. 16, 2023),https://bit.ly/3VZvDgw.

3 Letter from Robert J. Kasunic, Assoc. Reg. of Copyrights, United States Copyright Office, to Van Lindberg, Partner, Taylor English Duma LLP 1 (Feb. 21, 2023),https://bit.ly/3xxGlkU.

5 Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53, 58 (1884).

7 Naruto v. Slater, 888 F.3d 418, 426 (9th Cir. 2018).

8 Thaler v. Perlmutter, 687 F. Supp. 3d 140, 146 (D.D.C. 2013), appeal filed, No. 23-5233 (D.C. Cir. filed Oct. 18, 2023).

9 17 U.S.C. § 101; Feist Publ'ns, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340, 360 (1991).

10 Inventorship Guidance for AI-Assisted Inventions, 89 Fed. Reg. 10043, 10044 (Feb. 13, 2024).

11 Id. at 10045(citing Thaler v. Vidal, 43 F. 4th 1207, 1213 (Fed. Cir. 2022), cert denied,143 S. Ct. 1783 (2023)).

12 Beech Aircraft Corp. v. EDO Corp., 990 F.2d 1237, 1248 (Fed. Cir. 1993).

13 Inventorship Guidance for AI-Assisted Inventions, 89 Fed. Reg. at 10046–47 (citing Burroughs Wellcome Co. v. Barr Labs., Inc., 40 F.3d 1223, 1228 (Fed. Cir. 1994)(citing Mohamad v. Palestinian Auth., 566 U.S. 449, 454 (2012))).

14 Id. at 10047–48 (citing Pannu v. Iolab Corp., 155 F.3d 1344, 1351 (Fed. Cir. 1998)and citing35 U.S.C. § 115(a)).

15 Li Su Liu Qin Hai Zuo Pin Shu Ming Quan, Xin Xi Wang Luo Chuan Bo Quan Jiu Fen An (李某某訴劉某某侵害作品署名權、信息網絡傳播權糾紛案) [Case of Infringement against the Right of Authorship and the Right to Network Dissemination of Information], Jing 0491 Min Chu 11279 (BIC 2023) (CN),https://bit.ly/3VWf6K2.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.