Overview and Summary

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) filed 27 professional liability suits naming 222 directors and officers of 26 banks2 that failed during the credit crisis3 ("D&O" litigation) through March 2012. Some commentators have noted that these filings relate to only a small fraction of the 430 bank failures over the same period; however, careful analysis reveals much more:

- At this pace, ultimately directors and officers of 20% of

failed banks—86 in all—will likely face

suits.

- Directors and officers of more than half the largest failed

banks will ultimately be involved in FDIC professional liability

litigation.

- Some of the D&O suits already authorized and likely soon to

be filed could equal or exceed the largest claim to date of $900

million, but the FDIC appears to be litigating against the

directors and officers of a smaller proportion of banks than

following the savings and loan (S&L) crisis.

- The FDIC has filed at least five lawsuits against law firms and

collaborated with the SEC, which has brought its own accounting

claims against directors and officers. Cases against lawyers and

accountants were a major feature of failed bank litigation

following the S&L crisis suggesting there may be many more to

come.

This paper starts by providing an update on the timing and size of the bank failures that have given rise to FDIC lawsuits. We then explain how we developed our ultimate forecast of 86 cases. We compare the rate of filings currently to the filing rate of S&L crisis suits as a way of benchmarking the assertiveness of the FDIC's current enforcement stance in cases against directors and officers, lawyers, and accountants. We then analyze how the amount of losses incurred by the Deposit Insurance Fund ("DIF losses") affects litigation exposure and reveals a much higher filing rate for banks with higher losses. We explain how data on authorized suits reveal that some very large lawsuits are likely to be filed soon. Finally, we assess the significance of the observation that litigation has progressed more quickly in some states than in others.

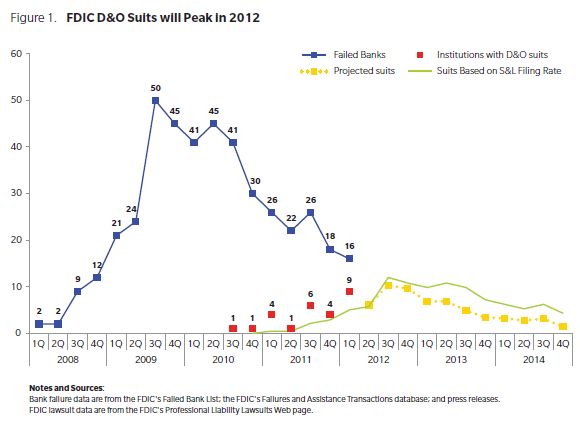

The timing of FDIC lawsuits follows the pattern of bank failures

The rise in FDIC D&O lawsuit filings in recent months mirrors the pattern of bank failures from about three years ago. We believe the peak in bank failures three years ago will likely be reflected in a peak in FDIC lawsuits in 2012. The typical three-year lag between failure and filing is the result of the three-year statute of limitations for the FDIC to file tort claims, although this limit varies by state.4 Thus, the pattern of bank failures influences the timing of FDIC lawsuits and can be used as the basis for a forecast.

We estimate directors and officers of 86 banks will ultimately be named in FDIC litigation

The FDIC has authorized suits against the directors and officers of 54 institutions through March 2012, but this does not represent a ceiling on the expected number of cases. Information from the lawsuits filed against directors and officers of 26 banks combined with the information about the timing and size of the corresponding bank failures provides insights about the pattern of filings that can be expected over the coming years. We produce an estimate of future filings associated with failed banks that are yet to have a director or officer named in an FDIC lawsuit by applying the pattern of filing rates observed to date5 to the history of bank failures.6 The resulting estimate that 86 banks will be involved in FDIC D&O litigation reveals that about 60% of the ultimate number of lawsuits has been authorized to date.

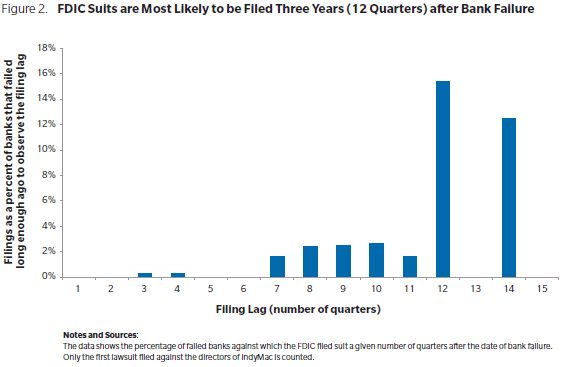

Comparing the dates of bank failures and subsequent filings reveals that the FDIC does not file all of its suits at the three-year statute of limitations deadline. The FDIC has filed a lawsuit as early as the third quarter following bank failure (i.e., between six and nine months later) and as late as 14 quarters after failure (see Figure 2).7 For each time interval, there are only a limited number of banks that failed sufficiently long ago to be involved in a lawsuit with exactly the specified lag. For example, there are 39 banks that failed three or more years ago (as of the end of March 2012) so the 6 lawsuits filed three years (12 quarters) after failure represent a 15 percent filing rate.8

The rate of FDIC filings today is lower than during the S&L crisis

While 27 cases have been filed, the litigation itself has hardly begun, making it hard to judge the FDIC's performance to date or to know how vigorously it will pursue these cases. However, a comparison of the scale of the filings here to filings after the S&L crisis does provide some basis to judge the FDIC's appetite for litigation. For the purpose of this comparison, we consider only professional liability suits brought by the RTC or FDIC in connection with the failure of insured depository institutions between 1985 and 1992.9

The S&L crisis experience provides a reasonable benchmark for current litigation because the factors contributing to bank failure and the professional liability claims being made by the FDIC are similar. According to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the economic conditions during the S&L era were secondary to poor management and other internal problems in explaining bank failure, and these factors were similar to those reported in Material Loss Reviews of recent bank failures.10 Furthermore, the management problems and internal problems identified by the OCC are similar to the professional liability claims being made by the FDIC today.11 However, the economic conditions during the recent credit crisis were distinct from conditions during the S&L crisis. The contributing role of commercial real estate losses in recent bank failures may make it harder to prove directors and officers were negligent rather than simply vulnerable to the consequences of a nationwide real estate market crash.

Above, we predict that the FDIC is on track to bring suits against directors and officers of 20% of the 430 banks that failed since the beginning of the credit crisis.12 This compares to a rate of 24% following the S&L crisis.13 If all FDIC lawsuits this time around were filed exactly three years after bank failure at the average filing rate observed following the S&L crisis, we would instead have expected a total of 103 suits. As shown in Figure 2, initial filings have exceeded this benchmark level but are expected to fall below it in the future.14 While the lower filing rate compared to the S&L crisis could indicate less assertive enforcement of professional standards, some evidence suggests that the FDIC's current efforts could match its S&L crisis performance in terms of aggregate recoveries. The FDIC's insured losses in the S&L crisis were close to $100 billion, or an equivalent of $185 billion adjusted for inflation.15 This amount is about twice the $90 billion in DIF losses that have been incurred since the beginning of 2008. We use our forecast16 and recent settlements17 to estimate ultimate recoveries of $1.9 billion. This is only 20% lower than S&L D&O litigation recoveries, which amounted to $1.3 billion from 1990 to 1995 (or $2.3 billion adjusted for inflation). This would reflect a rate of recovery on insured losses nearly double what was secured through corresponding S&L litigation.

FDIC claims against professional advisors are beginning to be filed

The FDIC was active in litigating professional liability claims against professional advisors of failed banks following the S&L crisis.18 The FDIC has begun to file similar claims in credit crisis cases. It has filed lawsuits against law firms that advised failed banks and coordinated with the SEC, which has leveled accounting claims against bank executives although not yet against accounting firms.

The FDIC has filed at least four separate malpractice lawsuits against law firms and one in which a law firm is named alongside directors and officers.19, 20 Separate from its D&O claims, the FDIC has also "authorized 29 other lawsuits for fidelity bond, insurance, attorney malpractice, appraiser malpractice, and RMBS claims."21 When these cases are filed, we will discover how many involve legal advisors to the failed banks. By comparison, the S&L crisis spurred 205 claims against lawyers and 139 claims against accountants compared to 883 D&O claims.22 More losses were recovered from law firms and accounting firms than from directors and officers (see Hinton 2010, Figure 16) in the aftermath of that crisis.

Cases were brought against lawyers following the S&L crisis for actions ranging from failing to record a lien to allegations that attorneys played a central role in aiding and abetting self-dealing.23 A common attorney malpractice claim was the failure to advise management of violations of regulations and statutes, usually concerning imprudent loans or failure to oversee a particular transaction.24 The allegations made in the FDIC's recent attorney malpractice suits are not dissimilar, for example, facilitating self-dealing by creating false settlement statements25 and failing to obtain a release of a security deed on collateral property when closing a loan transaction.26

With the assistance of the FDIC, the SEC has made claims of accounting violations in two recent cases against failed bank executives.27 However, in neither of these cases were accounting firms named. In the United Commercial Bank case, the SEC alleges the CEO and CFO concealed the deterioration of the bank's loan portfolio and inflated its reported earnings. In the Franklin Bank case, the SEC alleges the CEO and CFO misrepresented the bank's financial condition to potential buyers through an aggressive loan modification program that had the effect of converting nonperforming loans into performing assets in the third quarter of 2007. A five-year statute of limitations applies to SEC actions under federal law,28 giving the SEC additional time to bring such cases. However, the fact that the only two accounting cases brought to date were both in connection with bank failures that imposed some of the largest DIF losses ($1.4 billion in each case) suggests that smaller bank failures have not been a focus of FDIC accounting concerns to date.

The FDIC alleged breaches of duty by accountants during the S&L crisis in connection with loan loss reviews and audits of internal controls.29 Specific examples of FDIC accounting malpractice claims include: failing to perform an adequate review of a sample of delinquent loans; failing to require a write-off of loans that have been "permanently impaired;" allowing securities that are readily marketable to be reported at book value rather than their lower market value, as appropriate; or failing to identify an important internal control deficiency which delayed or prevented faulty underwriting, fraud, and noncompliance with regulations from being detected.30 These audit issues likely played a similar role in helping management identify and manage financial distress during the recent credit crisis. We have identified no obvious differences in the causes of recent bank failures that should cause accountants to expect a decreased likelihood of being sued by the FDIC than after the S&L crisis.

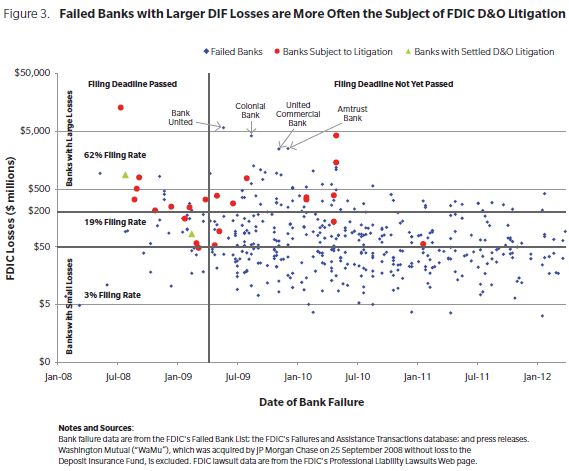

Directors and officers of banks with higher losses are more likely to be sued

The FDIC's filings to date reveal which banks are more likely to become the subject of D&O suits. In theory, the directors and officers of the largest failed banks are the biggest targets for litigation, but such cases may also present greater challenges in proving the connection between fiduciary failings and losses, for example, due to greater complexity of their operations and more widely distributed responsibility for decision-making and supervision. We find that banks with DIF losses greater than $200 million have filing rates of 62%. We also observe that only one case has been filed involving a bank with losses of less than $50 million, reflecting a very low risk that the directors and officers of banks with smaller losses will face litigation (a rate of 3%). The FDIC may decide not to litigate smaller cases because the cost of litigating even a small claim is significant. Thus, it cannot be inferred that the directors and officers of smaller failed banks were less culpable for DIF losses. For banks with DIF losses between $50 and $200 million, the filing rate has been 19%.

Figure 3 shows the filing rates of FDIC D&O suits to date and the corresponding size and timing of bank failures.31 The banks associated with D&O suits are depicted as circles and banks with settled cases as green triangles.32 Figure 3 also highlights the four banks with DIF losses in excess of $2 billion that are not yet the subject of FDIC litigation. The vertical black line indicates where the three-year federal statute of limitations deadline currently falls. This deadline has passed for banks to the left of this line.

The FDIC's low filing rate in cases involving DIF losses below $50 million is remarkable when compared to what happened after the S&L crisis. A much higher proportion—64% more—of the institutions that failed during the S&L crisis had insured losses that were less than $50 million (after adjusting for inflation).33 If the FDIC had filed S&L lawsuits at current rates, with only 3% of these smaller bank failures being targeted, the overall filing rate at that time would have been only 11%. The actual S&L rate of 24% was more than twice this level, suggesting a much more aggressive stance in S&L litigation when smaller losses were at stake.

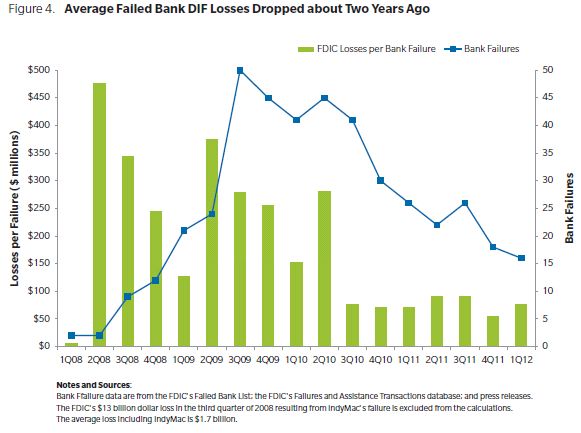

The lower risk of FDIC litigation for directors and officers associated with smaller bank failures (in terms of DIF losses) will likely have an important influence on the number of future lawsuits because banks that failed more recently were predominantly smaller banks. Figure 4 shows that, since the third quarter of 2010, average DIF losses have dropped; for many of the banks that failed most recently, DIF losses were below $50 million (see Figure 3). The FDIC's smallest claim made in a D&O lawsuit to date was for $6.8 million in connection with the Bank of Asheville, which caused DIF losses of $56 million.34 If this is the smallest claim that the FDIC judges to be economically viable, then unless the FDIC makes claims for a much larger proportion of DIF losses in cases with small losses,35 it is likely that the rate of filings against directors and officers of banks with DIF losses less than $50 million will remain de minimus. However, it is also possible that experience litigating similar community bank cases will encourage the FDIC to bring smaller cases in the future, particularly if larger cases are resolved and additional resources are made available.

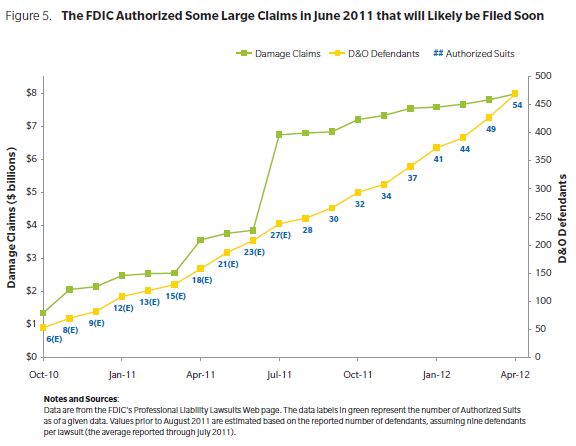

Some of the largest suits to date have been authorized and are about to be filed

The FDIC has a lot at stake in its largest cases because the top five suits filed to date represent 70% of the aggregate value of the filed claims. For this reason, it is noteworthy that several claims, potentially larger than any filed to date, have been authorized and could be filed very soon.

Figure 5 shows that the reported value of claims authorized through June 2011 rose by an aggregate value of $2.8 billion compared with the total from the prior month. These $2.8 billion in claims were authorized against 30 directors and officers. Given that an average of nine defendants have been named in the D&O suits authorized to date, it is likely that three or four lawsuits with an average value of $700 million or $900 million per suit will result from these claims.36 The previous highest claim was made against WaMu's directors and officers for $900 million, making it likely that these upcoming suits will be larger than almost all those filed to date.

There are few failed banks with DIF losses large enough to give rise to claims of this magnitude, making it very likely that claims will be made against the directors and officers of the largest failed banks that are not yet the subject of litigation. As shown on Figure 3, the four largest of these banks are Bank United, Colonial Bank, Amtrust Bank, and United Commercial, with DIF losses of $5.8 billion, $4.2 billion, $2.5 billion, and $2.5 billion respectively.37 If the suits authorized in June are associated with these banks, the claims (totaling $2.8 billion) would amount to 19% of DIF losses (totaling $15 billion), close to the average claim size to date. If these claims are instead brought against the directors and officers of three or four banks with smaller losses, they would represent an unusually high percentage of DIF losses.

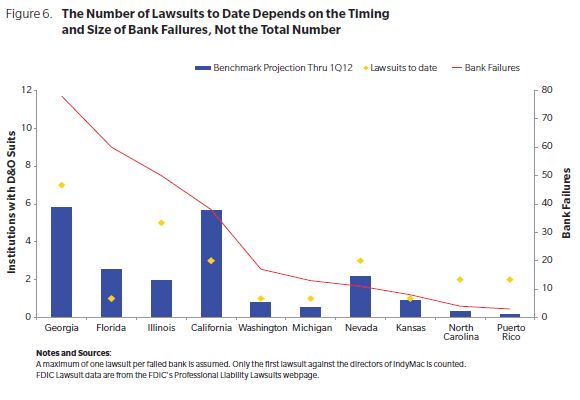

Litigation has progressed more quickly in some states than in others but largely as expected

Several commentators have remarked that many cases have already been filed in Georgia, with relatively few in California and Florida. However, these patterns are largely expected based on the size and timing of bank failures in the states.38 By comparing actual suits in each state with our claims forecast, we can identify states with higher or lower numbers of lawsuits than expected.39

The 10 states shown in Figure 6 are all those in which failed banks associated with FDIC D&O litigation were headquartered. They appear in declining order of the number of bank failures in each state. Relatively high levels of litigation are observed in Illinois, Nevada, North Carolina, and Puerto Rico. On the other hand, the filings involving California and Florida banks are fewer than the numbers expected to date.

In Minnesota, Missouri and Arizona, bank directors and officers have yet to be named in any lawsuit even though these states are in the top ten in terms of bank failures. However, the later timing and lower DIF losses in these states mean that litigation involving banks from these states was not forecast to occur until after the first quarter of 2012.

Conclusion

The FDIC is just beginning to litigate its claims against directors and officers of banks that failed during the credit crisis. It is possible that early litigation successes or failures could influence the rate of future filings. However, if filings continue to follow the patterns observed to date, there will be less professional liability litigation associated with failed banks than following the S&L crisis.

*This paper is the second in a series on FDIC professional liability litigation. The first paper described the background to this litigation, the causes of bank failures following the credit crisis, and comparisons with the aftermath of the savings and loan crisis. Paul J. Hinton, "Failed Bank Litigation, The economics of recent bank failures, comparisons with the S&L crisis, and implications for litigation against directors and officers," 16 August 2010, http://www.nera.com/67_7270.htm ("Hinton 2010").

Footnotes

1.Paul J. Hinton is a Vice President and Zachary Slabotsky is an Associate Analyst with NERA Economic Consulting. The authors thank their colleagues Denise Martin, Jerry Arnold, and Bernard Shull for their comments on an earlier draft. The authors also acknowledge the expert input from Chip McDonald of Jones Day.

2.We use the term "bank" to refer to any FDIC insured institution. Of the 27 FDIC D&O suits filed through March, two were filed against executives from IndyMac.

3.Bank failures since the beginning of 2008.

4."The FDIC has three years for [federal] tort claims and six years for breach-of-contract claims to file suit from the time a bank is closed. If state law permits a longer time, the state statute of limitations is followed." FDIC Professional Liability Lawsuits, http://www.fdic.gov/bank/individual/failed/pls/, accessed 10 April 2012.

5.For this purpose, we treat the one filing in Figure 3 that occurred more than three years after bank failure as if it had been made in the 12th quarter.

6.We have also estimated a proportional hazard model that yields a similar projection.

7.Surprisingly, the FDIC filed its suit against Silver State Bank about three and a half years after it failed. This may make its common law negligence claims vulnerable to Nevada's three-year statute of limitations. (Nevada Revised Statutes, Chapter 11 "Limitations of Actions," §190 "Periods of limitation," http://www.leg.state.nv.us/nrs/.) (The FDIC's suit against First National Bank of Nevada was filed in Arizona a year and four weeks after the bank failure and so may also be vulnerable to a statute of limitation defense. Based on the precision of the analysis in Figure 3, however, it appears as being filed with a lag of 12 quarters.)

8.There are relatively fewer banks that failed sufficiently long ago to give rise to lawsuits with longer lags. For example, 5 lawsuits were filed 8 quarters after bank failure (i.e. two years) out of a total of 205 banks (excluding one that was previously the subject of D&O litigation) that failed eight or more quarters ago, giving a filing rate of 2.4%; whereas the six lawsuits filed 12 quarters after bank failure (i.e., three years) represent over 15% of the 39 banks (excluding seven that were previously the subject of D&O litigation) that failed at least three years ago and were not the subject of previous suits.

9. For further discussion and development of these data, see Hinton 2010, pp. 14-17.

10.Hinton 2010, pp. 16-17

11. Hinton 2010, Figure 13.

12. There were 430 bank failures from the beginning of 2008 through March 2012. See FDIC Failed Bank List.

13. See, e.g., Hinton 2010, Figure 14.

14. Two factors contribute to this relatively higher rate of filings to date. First, some lawsuits were filed well within the three-year federal statute of limitations deadline used as a benchmark in this figure. Second, earlier bank failures were larger (in terms of DIF losses) and the larger failures have been more frequent targets of the FDIC. See Figure 3.

15. DIF losses for each bank are expressed in February 2010 dollars adjusting for inflation. February 2010 is the weighted average mid-point of the credit crisis DIF losses.

16. Our forecast of the ultimate value of FDIC claims adds $1 billion on top of the $8 billion authorized through March. In the majority of suits the FDIC has claimed between 12 and 20% of DIF losses. As future suits are filed in connection with bank failures that involved lower DIF losses, the average size of FDIC claims is expected to decline.

17. The recoveries already realized in two settlements for which the amounts were disclosed (WaMu and First National Bank of Nevada) were close to 20%. Three defendants in the WaMu case settled for $65 million on 13 December 2011. Claims against 12 other WaMu directors and officers were resolved as part of a $125 million settlement. In aggregate, these settlements represent a $190 million recovery in connection with the FDIC's claim of $900 million. The defendants in the First National Nevada case settled a $193 million claim for $40 million on 2 September 2011. The terms of a third settlement with directors and officers of Corn Belt Bank and Trust Company on 10 May 2011 have not been disclosed.

18. See FDIC, "Managing the Crisis: The FDIC and RTC Experience," Professional Liability Claims, Chapter 11. In S&L litigation, the FDIC also recovered about $1 billion from Drexel Burnham Lambert, Inc.'s bankruptcy estate and from Michael Milken, the former head of Drexel's "junk bond" unit. These recoveries resolved claims of fraud including alleged misrepresentation of the value, liquidity, and risk associated with junk bonds sold to thrifts. In the aftermath of the recent credit crisis, the FDIC has made damages claims in connection with bank losses incurred on subprime MBS and CDO securities. These suits could be a significant source of recoveries this time around.

19 FDIC v. Mahajan, No. 11-cv-7590 (N.D. Ill. Oct. 25, 2011).

20. Attorney malpractice suits have been reported in the news media against attorneys for Integrity Bank (suits against two firms), First Priority Bank, and Neighborhood Community Bank. Meredith Hobbs, "Failed real estate deals driving malpractice claims," Fulton County Daily Report, 19 July 2011; Jane Meinhardt, "Lawsuits aim at professional service firms," Tampa Bay Business Journal, 13 January 2012.

21 FDIC Professional Liability Lawsuits, http://www.fdic.gov/bank/individual/failed/pls/, accessed 10 April 2012. The FDIC does not list accountants on its Professional Liability Lawsuits Web page as subject to the cases it has filed against professional advisors.

22. Hinton 2010, Figure 14.

23. FDIC, "Managing the Crisis: The FDIC and RTC Experience," Professional Liability Claims, Chapter 11, ("Managing the Crisis"), p.281.

24. Ibid.

25. The FDIC alleges that Smith Welch & Brittain created two conflicting sets of "settlement statements" to facilitate loans on the basis of inflated property values. Scott Trubey, "Alleged Law firm liable in bank failure, feds say," The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 8 February 2011.

26. Andy Peters, "FDIC claims Gwinnett firm botched closing," Fulton County Daily Report, 25 October 2010.

27. "SEC charges bank executives with hiding millions of dollars of losses during 2008 financial crisis," SEC Litigation Release No. 22121 / 11 October 2011. "SEC charges Texas bank holding company's CEO and CFO with misleading investors about loan quality and financial health during the financial crisis," SEC Press Release 2012-55, 6 April 2012.

28. Section 2462 of Title 28 of the United States Code.

29. Managing the Crisis, pp. 278-280.

30. Ibid.

31. Exact DIF losses caused by each bank failure remain uncertain as long as the bank's receivership continues, for example loss sharing agreements can extend 10 years or more in relation to residential loans. Consequentially, loss estimates are updated annually in the FDIC's Failures and Assistance Transactions database. We use loss estimates as of 31 December, 2010, as these were the most recent available through the database as of 20 April 2012. For banks that failed in 2011 and 2012, loss estimates cited in the FDIC's bank closing press releases are used.

32. The WaMu settlement is not shown. The failure of WaMu did not result in any DIF loss. However, this failure is classified as a case with large losses for the purpose of estimating the filing rates in each size category, as WaMu was the largest bank to fail as measured by assets.

33. DIF losses for each institution are expressed in February 2010 dollars adjusting for inflation. February 2010 is the weighted average mid-point of the credit crisis DIF losses.

34. The FIDC has made some smaller claims in suits against bank attorneys: see, for example, the $1.1 million claim in the FDIC action in connection with the failure of Integrity Bank (FDIC v. Jampol, Schleicher, Jacobs & Papadakis, L.L.P.) for mishandling a closing. R. Robin McDonald, "FDIC targets lawyer in bad loan suit; AS RECEIVER for Integrity Bank, FDIC wants more than $1 million in malpractice claim," Fulton County Daily Report, 2 August 2011.

35. The FDIC has made claims of similar size, as a proportion of DIF losses, in all its cases to date with the exception of WaMu and IndyMac, which were the only banks to fail with assets in excess of $30 billion. The average claim size in the FDIC's D&O suits associated with other banks is 16% of DIF losses, equivalent to $8 million in a case with DIF losses of $50 million.

36. Prior to August 2011, the FDIC reported the cumulative number of directors and officers named in authorized suits but did not report the associated number of lawsuits. Since then, the FDIC has reported the number of associated lawsuits. Overall, an average of nine defendants has been named per suit.

37. Data are from the FDIC's Failures and Assistance Transactions database. Loss estimates are as of 31 December 2010.

38. It should also be noted that from a purely statistical point of view, since there are 50 separate states, the chances of observing at least a few states with levels of filings that on their own would be considered unusual is in fact expected. This is an example of the well-known multiple comparisons problem. See, e.g., David H. Kaye and David A. Freedman, "Reference Guide on Statistics," Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence, Second Edition, Federal Judicial Center, 2000, p. 166.

39. A higher propensity to bring claims in particular states compared to our prediction could be the result of, for example, variation in the severity of fiduciary failures by banks in each state, different assessments of the strength of the FDIC's legal case in each state, or a different appetite for litigation.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.