Article by Elaine Buckberg and Ronald I. Miller1

To read this article and its footnotes in full please click here.

The government and Federal Reserve have continued to write policy at an unprecedented rate since our September 26 and October 10 notes on the Paulson Plan and the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008. This note describes the extraordinary sequence of policy developments from the Federal Reserve, US Treasury, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and central banks abroad. We attempt to provide insights into the motivation for these policies and to place them in context, pointing to how fast and how dramatically the interventions have developed. This note places particular emphasis on the critical role of the Federal Reserve in creating liquidity domestically and internationally. The final section discusses prospective policies to provide relief in the housing market, which remains a subject of active debate.

A Wave Of Policies

Since the Lehman Brothers' bankruptcy filing on September 15, 2008, the Federal Reserve, Treasury, and FDIC have introduced an extraordinary series of new policies designed to stimulate credit market liquidity, renew market confidence, and avert a sharp and deep recession. Foreign governments and central banks have also taken extraordinary measures, many of which have been coordinated across borders. Never before in history have there been government interventions in financial markets on this scale. This paper puts these extraordinary policy measures into context.

In introducing new policies in response to deteriorating credit and financial market conditions, the government has made clear that the additional policies are designed to complement, not substitute for, previously announced policies. For example, the March 13, 2008 announcement that Treasury would inject $250 billion of capital into US banks, an option that critics of the Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP) floated while the TARP was before Congress, was introduced as a supplement to the plan to purchase mortgage-related assets from financial institutions. However, the capital injections will be financed from the same $700 billion approved by Congress under the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008. Indeed, the $250 billion accounts for the entirety of the initial commitment of funds that do not require further Presidential or Congressional approval. Policymakers have not only been innovative in the policies they have introduced, but they have also signaled that they will continue innovating as needed to stabilize markets and alleviate the financial crisis.

The Banking Crisis Playbook

The asset purchase program that was initially proposed appears to have been designed to address a financial panic. As we discussed in our September 26 paper, the asset purchase plan would be an effective, although not necessarily sufficient, policy if financial panic has driven prices for troubled assets below the discounted value of their cash flow.2 The new policy of aggressive capital contributions to the commercial banking sector is a classic policy prescription for a banking crisis and, as noted in our previous papers, was recommended by many economists as a potential alternative to the asset purchase plan. It seems clear that policy makers now believe that we are facing both a financial panic and a banking crisis, with the former addressed in part by the asset purchase plan and the latter addressed by the recapitalization of the banking sector.

The scale of the current crisis exceeds anything seen since the Great Depression. The largest banking crisis experienced in the US since the Depression was the S&L crisis of the late 1980s and early 1990s. The total assets of banks closed by federal authorities during that crisis were $519 billion.3 By way of comparison, the assets of Lehman Brothers alone were greater than $600 billion when it declared bankruptcy. While costly, the S&L crisis did not seriously threaten the overall stability of the banking system.

Despite the extraordinary magnitude of the current crisis, in many respects it looks much like other banking crises. While the US has not experienced a full-scale systemic bank crisis since the Great Depression, globally we have seen periodic banking crises in both developed and less developed countries. By one count, more than 100 systemic banking crises have occurred since the late 1970s.4 Soberingly, analysis of these crises has found that on average they lead to fiscal costs greater than 10% of GDP.5 Were the US to follow that pattern, the total would be about $1.5 trillion.

International economic policy specialists have studied banking crises around the globe and come to a fairly strong consensus about both the characteristics of banking crises and appropriate strategies to deal with them.6 Versions of these consensus strategies are often advocated by international organizations such as the International Monetary Fund and the Inter-American Development Bank.7

A systemic banking crisis is generally defined as a crisis of solvency, not just of liquidity. The asset purchase plan was designed to address liquidity, and the new capital injection plan is designed to address solvency. A bank crisis starts with some event that causes losses across a broad swathe of the banking industry. There are many possible sources of large aggregate losses and of course it was losses in mortgage-backed securities that largely led to the current crisis. The source of the losses is not necessarily important for the design of strategies to solve the crisis. What matters is that these losses lead to a reduction in bank capital. Capital requirements are central to the prudential regulation of banks in the US and internationally under the Basel Accords. One difference in the current crisis is that it has extended beyond the commercial banking system to involve non-deposit-taking institutions such as Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns. They were effectively integrated into the banking system via the securitization of mortgages: both firms were active in securitization and held large portfolios of mortgage- and asset-backed securities. One remarkable aspect of the crisis is that in approximately six months, large independent investment banks have been eliminated—via bankruptcy (Lehman Brothers), acquisition by a bank holding company (Bear Stearns, Merrill Lynch), or conversion to a bank holding company (Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley).

US policymakers appear to be playing out of the consensus playbook. The timelines of the policies that we provide below and in Appendix A illustrate the pattern of the international consensus on dealing with banking crises.8 The outline of this consensus approach is as follows: the first step is encouraging free-market solutions, such as helping banks and other financial institutions find private sources of capital. Citigroup and other large banks have successfully done so. The next step is to help merge ailing banks into stronger banks, without government assistance if possible, as with Wachovia, or with government assistance if necessary, as with Washington Mutual. The goal of such mergers is to create a merged entity with a balance sheet healthy enough to go forward. Banks that are in the most severe trouble are to be closed quickly and liquidated, as with IndyMac. If these measures are not enough, then more direct intervention is called for. Least intrusive among direct actions is lender-of-last-resort lending, although this addresses only liquidity issues and not solvency issues. The Fed has been aggressively lending from the discount window. Next is just what Treasury has done: large injections of capital into the banking system. The most extreme intervention is outright nationalization.

The Japanese banking crisis that followed the bursting of the so-called bubble economy and that lasted through the 1990s has been studied by many economists, notably Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, and the lessons learned from it have informed much discussion of the current crisis. Some economists attribute a decade of economic weakness to that crisis and the policy response that it engendered. Many economists criticized the Japanese policy response for being slow to admit to the problems in the banking sector and even slower in taking action. Economists frequently argue that acting quickly to resolve a banking crisis is important in determining the final cost of the crisis.9 The policy response to the current crisis has been, as we document below, both fast and aggressive.

Fed And Treasury Roles

The Fed had a balance sheet of $800 billion as of the end of September 2008. Because of its unique position as central bank, the Fed can expand this balance sheet at will, unlike any private institution. However, to make asset purchases beyond the size of its current balance sheet, it needs to create new money, which may lead to inflationary pressure. In contrast, the administrative branch can fund its initiatives by issuing debt. Public sector debt issuance creates a risk of crowding out private sector investments and may create upward pressure on interest rates, but is not directly inflationary.

Table 1. Treasury and FDIC Initiatives in Response to the Credit Crisis

|

Name |

Description |

Intended Effect |

Start Date |

|

|

TREASURY |

Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) |

Purchase troubled assets, including residential or commercial mortgages and securities backed by them, from financial institutions in amounts totaling up to $700 billion.A Institutions selling troubled assets must provide either securities or warrants to purchase nonvoting common or preferred stock.B |

Improve balance sheets of financial institutions; eliminate uncertainty about marks on mortgage- related asssets. |

Undetermined |

|

Equity purchase program (capital injections) |

Purchase preferred stock in banks, using $250 billion of the $700 billion authorized under the TARP. Banks provide warrants to purchase common stock equal to 15% of the amount of preferred stock purchased. $125 billion has been committed to nine major banks.C |

Improve capital position of banks prevent runs on healthy banks; promote lending in interbank market and bank lending to commercial and retail customers. |

10/13/08 |

|

|

Insurance program |

Guarantee troubled assets, including mortgage- backed securities, originating prior to March 14, 2008.D |

Offer insurance protection to financial institutions that continue to hold troubled assets. |

Undetermined |

|

|

Money market guarantee program |

Guarantee the share price of any publicly offered eligible money market mutual fund, retail or institutional, that applies for and pays a fee to participate in the program.E,F |

Prevent redemptions from money market funds, which would in turn prevent large-scale selling of commercial paper and reduce business access to credit. |

9/29/08 |

|

|

FDIC |

Insuring deposits up to $250,000 per depositor |

Raise the limit on federal deposit insurance coverage from $100,000 to $250,000 per deposit.G |

Prevent bank runs. |

10/03/08 |

|

Unlimited insurance for non-interest- bearing deposits |

Provide full deposit insurance coverage for non-interest-bearing deposit transaction accounts, regardless of dollar amount.H |

Prevent businesses from withdrawing deposits over $250,000 limit from banks. |

10/14/08 |

|

|

Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program |

Guarantee newly issued senior unsecured debt of banks, thrifts, and certain holding companies.H |

Ensure bank access to credit markets, in turn assuring their ability to lend to customers. |

10/14/08 |

Notes And Sources:

A. "Interim Assistant Secretary for Financial Stability Neel Kashkari Remarks before the Institute of International Bankers," US Department of the Treasury, October 13, 2008. http://www.ustreas.gov/press/releases/hp1199.htm

B. H.R. 1424, 110th Congress, § 113(d)(1).

C. "U.S. Government Actions to Strengthen Market Stability," US Department of the Treasury, October 14, 2008. http://www.ustreas.gov/press/releases/hp1209.htm

D. H.R. 1424, 110th Congress, § 102(a)(1).

E. "Treasury Announces Temporary Guarantee Program for Money Market Funds," US Department of the Treasury, September 29, 2008. http://www.ustreas.gov/press/releases/hp1161.htm

F. "Treasury Announces Conclusion of Enrollment Period for Temporary Money Market Guarantee Program and Technical Correction," US Department of the Treasury, October 8, 2008. http://www.ustreas.gov/press/releases/hp1188.htm

G. "Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 Temporarily Increases Basic FDIC Insurance Coverage from $100,000 to $250,000 Per Depositor," FDIC, October 7, 2008. http://www.fdic.gov/news/news/press/2008/pr08093.html

H. "FDIC Announces Plan to Free Up Bank Liquidity," FDIC, October 14, 2008. http://www.fdic.gov/news/news/press/2008/pr08100.html

Monetary Policies

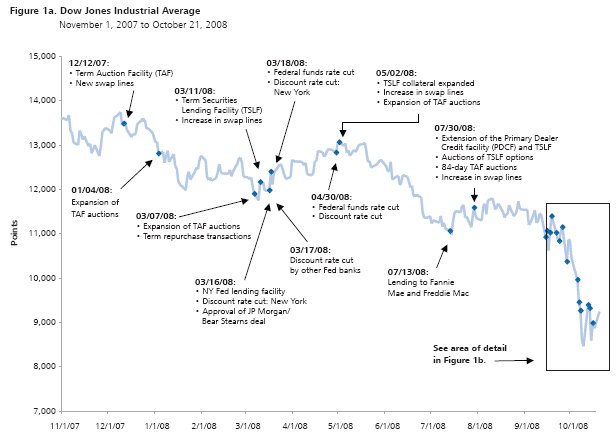

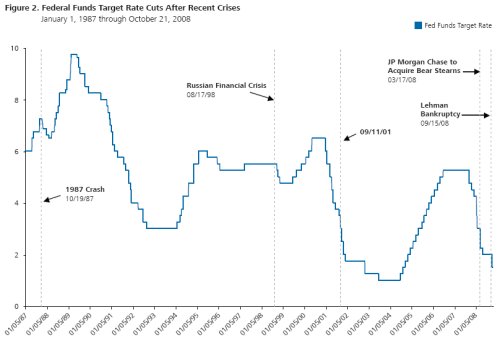

From Sunday, September 14, 2008 to Tuesday, October 21, 2008 the Fed announced 26 new policy initiatives or policy changes in 37 days, as shown in Figure 1 and Appendix A.10 After having already cut its benchmark federal funds target and discount rates by 3.25 and 4.00 percentage points, respectively, since August 2007, the Fed has since cut the fed funds target and discount rates by an additional 50 basis points and taken numerous initiatives designed to increase liquidity in the financial sector.11 Some of these policies have been designed to provide temporary liquidity to major financial institutions holding illiquid assets, while giving them time to restructure their balance sheets, with the greater objective of averting failures of financial institutions. All have been designed to improve access to credit in the economy in order to prevent or, increasingly, relieve the contractionary effect of shrinking credit on economic activity—in other words, to avert or mitigate a recession. These policies include interest rate cuts, lending to non-bank companies, expanded lending to primary dealers against a widening range of collateral, and the creation of swap lines with foreign central banks. All of these will be discussed below.

Whereas the Fed is well-known to set interest rates and be the lender of last resort to banks via the discount window, it is also empowered to serve as the lender of last resort to any party in times of crisis. Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act provides that "[i]n unusual and exigent circumstances," the Fed may loan to any party against notes, drafts, or bills of exchange collateral if that individual cannot "secure adequate credit accommodations from other banking institutions." All Fed lending must take the form of a swap, with the Fed lending cash in exchange for securities as collateral. However, in its initiative to purchase commercial paper, discussed below, the Fed will purchase securities directly from corporations by creating a special purpose vehicle to do so.

Interest Rate Cuts

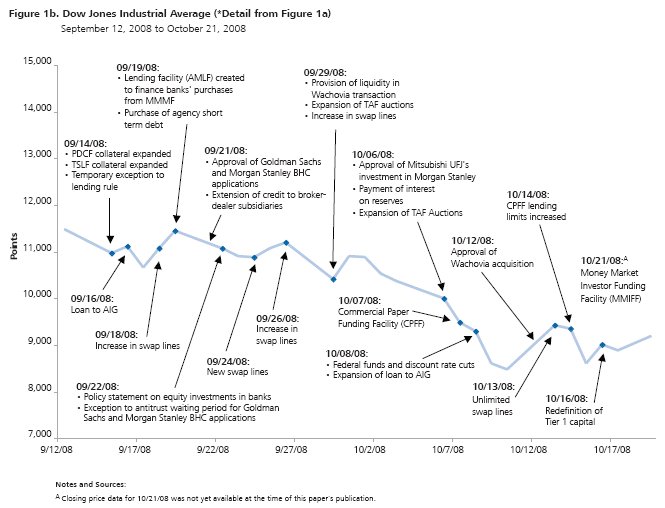

Past crises caused the Fed to begin cutting the benchmark fed funds target rate; in contrast, by the time Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy on September 15, the Fed had already cut the fed funds rate seven times for a total of 3.25 percentage points starting on September 18, 2007. Monetary conditions were already easy by historical standards, with the fed funds rate at 2.00%, as shown in Figure 2. In the past, the Fed's discount rate has been adjusted to match changes in the fed funds rate, which is the Fed's primary monetary policy target. However, in March 2008, in response to the collapse of Bear Stearns, the Fed lowered the discount rate without changing the fed funds rate, in order to signal to the market that it would make emergency funds available to banks at a lower rate, without adjusting its overall monetary policy.

Compared to past crises, the 50 basis-point cut on October 8, 2008, coordinated with six major central banks making simultaneous cuts, was extraordinary in terms of international cooperation. The Fed, the European Central Bank (ECB), Bank of England, Swiss National Bank, Bank of Canada, and Sveriges Riksbank (Sweden) announced jointly that they would all cut rates. In two past financial crises, major central banks followed Fed rate cuts. Following 9/11, the Fed cut rates by 50 basis points on September 17, followed by same-day cuts of 50 basis points by the ECB and Bank of Canada and a 25 basis-point cut by the Bank of England. Following the 1987 stock market crash, the initial rate cut was 37.5 basis points; the Bundesbank, Bank of England, and Swiss National Bank followed within two days. Following the Russian default and devaluation on August 17, 1998, the Fed did not cut rates for six weeks—and a month after Long-Term Capital Management's losses came to light on September 2, 2008—and then only by 25 basis points. No major central banks followed the initial rate cut, nor after two subsequent 25 basis-point cuts in October and November.

Table 2. Fed Funds And Other Major Central Bank Rate Cuts In Recent Market Crises Within Three Months Of Crisis Inception

|

Event |

Event Date |

Initial Fed Funds Rate |

Fed Funds Rate Cut |

Other Central Banks' Rate Cuts |

|||

|

Date |

Amount |

Bank Name |

Date |

Amount |

|||

|

Lehman Bankruptcy |

9/15/08 |

2.00 |

10/8/08 |

0.50 |

ECB |

10/8/08 |

0.50 |

|

9/11 |

9/11/01 |

3.00 |

9/17/01 |

0.50 |

ECB |

9/17/01 |

0.50 |

|

10/2/01 |

0.50 |

Bank of England |

10/4/01 |

0.25 |

|||

|

11/6/01 |

0.50 |

ECB |

11/8/01 |

0.50 |

|||

|

12/11/01 |

0.25 |

||||||

|

Russian Financial Crisis |

8/17/98 |

5.50 |

9/29/98 |

0.25 |

|||

|

10/15/98 |

0.25 |

||||||

|

11/17/98 |

0.25 |

||||||

|

1987 Market Crash |

10/19/87 |

7.25 |

11/4/87 |

0.375 |

Bundesbank |

11/6/87 |

0.50A |

|

1/5/88 |

0.25 |

||||||

Notes And Sources:

Bloomberg LP and www.bundesbank.de

A. This rate cut applies to the Lombard rate of the Bundesbank.

Because interest rates have been steadily cut over the past 14 months, the Fed has relatively little room to cut rates further. After 9/11, the Fed cut the fed funds rate four times in three months, by a total of 1.75 percentage points. Were the Fed to follow the same pattern now, the fed funds rate would fall to a mere 25 basis points. At already very low interest rates, the marginal stimulus effect of further rate cuts may be limited. It's also different to signal the start of what may be a program of interest rate cuts—as was the case after the 1987 crash, the Russian financial crisis, and 9/11—than to add another cut from an already very low rate. Another reason to hold the line on further cuts would be if members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which sets rates, are still concerned about inflationary pressure. Instead of further rate cutting, the Fed has focused its efforts on ensuring that the financial system has sufficient capital and liquidity to channel the Fed's more abundant funding on to the rest of the economy.

New Fed Funding Facilities

As the credit crisis has developed, the Fed has repeatedly found innovative ways to extend credit to the banking, non-banking financial, and corporate sectors at a rapid pace. The Fed's standard lender-of-last-resort role is to lend to domestic banks, typically overnight, against collateral. New facilities extended the Fed's lending by increasing loan maturities, liberalizing collateral quality requirements, providing credit to non-bank companies, and supplying liquidity to non-US banks.

Table 3. Federal Reserve Facilities Initiated In Response To The Credit Crisis As Of October 21, 2008

|

Facility |

Eligible Participants |

Terms |

Current Amount

Available |

Effective Dates |

|

Term Auction Facility (TAF) |

Depository institutions |

Fed holds auctions of fixed amounts of term funds; rate determined by auction; required collateral same as those types used to secure loans at the discount window.A |

$600 BB |

12/17/07A; last increase 10/06/08B |

|

Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF) |

Primary dealers |

Fed requires same collateral as those types eligible for pledge in tri-party funding arrangements through the major clearing banks.C |

Per borrower: margin-adjusted eligible collateral |

3/17/08 C |

|

Term Securities Lending Facility (TSLF) |

Primary dealers |

Fed holds weekly auctions; dealers must provide investment-grade debt securities as collateral.D |

$200 BD |

03/27/08E |

|

AIG Facility |

American International Group (AIG) |

$85 billion loan (24-month term at three- month LIBOR plus 850 basis points)F; $37.8 billion in AIG debt securities loaned to New York Fed in exchange for cash collateral.G |

$122.8 B |

09/16/08F; expanded 10/08/08G |

|

Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) |

Corporate issuers |

Fed will purchase three-month paper rated A1/P1/F1.H |

Per issuer: maximum amount issuer had outstanding between 01/01/08 and 08/31/08.H |

10/27/08I |

|

Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (AMLF) |

Depository institutions |

Fed lends to eligible institutions to finance purchases of high-quality asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) from money market mutual funds.J |

Per loan: an amount equal to the amortized cost of the ABCP pledged to secure the advance.K |

9/19/08K |

|

Swap Lines |

Foreign central banks |

Fed provides dollars to central banks for use in their jurisdictions. |

ECB: Unlimited |

Unlimited lines as of 10/13/08L |

|

Money Market Investor Funding Facility (MMIFF) |

Private sector special purpose vehicles (PSPVs) |

PSPVs may purchase commercial paper with remaining maturity of 90 days or less from financial institutions rated at least A1/P1/F1. Each PSPV may purchase from no more than ten financial institutions, and each institution's purchases may not exceed 15% of the assets of the PSPV.O |

Per PSPV: 90% of the purchase price of each eligible asset.O |

10/21/2008O |

Notes And Sources:

A. Federal Reserve Press Release, December 12, 2007.

B. Federal Reserve Press Release, October 6, 2008.

C. Federal Reserve Press Release, March 16, 2008

D. Federal Reserve Press Release, September 14, 2008.

E. Federal Reserve Press Release, March 11, 2008.

F. Federal Reserve Press Release, September 16, 2008.

G. Federal Reserve Press Release, October 8, 2008.

H. Federal Reserve Bank of New York, "Commercial Paper Funding Facility: Program Terms and Conditions," October 8, 2008.

I. Federal Reserve Press Release, October 14, 2008.

J. Federal Reserve Press Release, September 19, 2008

K. Federal Reserve Discount Window & Payments System Risk Release, September 29, 2008.

L. Federal Reserve Press Release, October 13, 2008.

M. Federal Reserve Press Release, October 14, 2008.

N. Federal Reserve Press Release, September 29, 2008.

O. Federal Reserve Press Release, October 21, 2008.

Longer-Maturity Lending To Banks

Contraction in short-term funding markets caused the Fed to introduce new lending facilities in December 2007. On December 12, 2007, the Fed announced the Term Auction Facility (TAF), a program to extend $40 million combined in 28- and 35-day financing to depository institutions, in contrast to the normal overnight funding. With the TAF, the Fed extended its reach to provide guaranteed month-long financing to domestic banks (lending is against collateral, as with overnight lending). The TAF has since been expanded to include 84-day and forward auctions with up to $900 billion available by December 31, 2008.

Lending To Investment Banks

In the week following the collapse of Bear Stearns, the Fed extended lending to the large investment banks that are designated primary dealers in Treasury securities. It was widely held that Bear Stearns was solvent at the time of its collapse, yet market concerns about its solvency caused the equivalent of a bank run: rapid withdrawals quickly rendered the long-time dealer illiquid and unable to meet immediate payment demands. To prevent further failures of securities firms, the Fed sought to give the largest dealers access to liquidity via loans in exchange for collateral. On March 11, 2007, the Fed created a $200 billion Term Securities Lending Facility (TSLF) through which it would give 28-day credit to primary dealers in exchange for collateral including Agency securities, Agency residential mortgage-backed securities, and AAA/Aaa-rated non-Agency residential mortgage-backed securities.12 The collateral eligible for the TSLF was expanded on September 14, 2008 to include all investment-grade securities.

On March 16, the Fed announced that primary dealers could also borrow from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York at the discount rate, as do banks. The discount rate was also cut 25 basis points to 3 ¼%, followed by a 75 basis-point cut in the fed funds rate to 2 ¼% on March 18; by March 20, the discount rate was cut another 75 basis points to 2 ½%, for a total cut of 1.00% in less than a week.

Lending To AIG And Other Corporations

On September 16, the Fed announced that it had used its lending powers under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act to provide an $85 billion loan to American International Group (AIG), the world's largest insurer. The loan, at an astonishingly high interest rate of LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate) plus 850 basis points, is secured by everything AIG owns.13 Further, 80% of AIG became owned by the US government as part of the transaction. As noted above, Section 13(3), added to the Federal Reserve Act during the Depression, allows the Fed to lend to any kind of institution.14 Before the Fed created the TSLF as a means to provide liquidity to investment banks under Section 13(3) in March 2008, as described above, the Fed had not invoked the Section since the 1930s.15 The TSLF made Fed money available to brokerages, but the loan to AIG extended the Fed's activities beyond the world of banking. This was, perhaps, recognition that AIG's losses, reportedly originating in its activities in credit default swaps and other credit derivatives, arose in essence from part of the banking system even though AIG was not subject to Fed banking oversight. On October 8, with the original credit line already exhausted, the Fed extended another $37.8 billion of credit to AIG, this time secured by investment-grade fixed income securities.

The Fed, already having moved its activities beyond its traditional realm of commercial banking, has also broadened the markets in which it operates. On October 7, the Fed announced the creation of another new lending facility, the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF), also under the authority of Section 13(3). The CPFF is structured in the form of a special purpose vehicle (SPV), funded by Fed loans, that will purchase unsecured and asset-backed commercial paper of three-month maturity directly from issuers, starting October 27. Fed involvement in the commercial paper market is new, but this is a market tightly related to the banking system, as much corporate paper is issued by banks or backed by bank lines of credit. The commercial paper market is important to the short-term financing activities of most large corporations. The credit crisis has led banks to hesitate about backing commercial paper and has led investors to worry about the solvency of borrowers. It has made commercial paper rates higher and made it difficult for firms to place commercial paper. The Fed is concerned that disruption to this market could lead to serious consequences in the broader economy by preventing companies from paying their bills.

With the CPFF, the Fed has effectively stepped in to be the lender of last resort to the corporate sector, in response to banks' shrinking lending. On one level the CPFF is a natural extension of the Fed's general concerns with financial market liquidity. On another level, it is an important expansion of Fed activity well beyond the banking sector. Because the CPFF extends the Fed's lending beyond banks and brokerages to much of corporate America, it must be organized under Section 13(3). This may also explain why the CPFF has been set up as an SPV and why PIMCO, an outside manager, has been contracted.

The CPFF does not substitute fully for normal private sector lending. The Fed will only purchase paper up to three months in maturity and only paper with the highest commercial paper ratings. Purchasing only top-rated paper parallels the strategy of assisting banks discussed above, i.e., providing credit to the strongest companies. The Fed has not stated any limit as to the total volume of commercial paper that might be purchased by the CPFF, but it has limited the amount purchased from any given issuer to the maximum amount the issuer had outstanding between January 1 and August 31, 2008.

Money Market Funds

The Fed became involved in the operation of money market mutual funds (MMMFs) following a September 19 announcement that the Fed was creating a new liquidity facility, the AMLF, that was designed to purchase corporate paper from MMMFs that were experiencing difficulties because of lack of liquidity in the corporate paper market.16 The immediate impetus for the policy was the threat that some MMMFs would "break the buck," i.e., drop below their standard share price of one dollar. In the days following the Lehman bankruptcy and AIG's failure, MMMFs were facing high investor redemptions, yet markets for their commercial paper assets, especially asset-backed commercial paper, were frozen. Forced sales under the current market conditions could have meant fire sale prices for normally liquid commercial paper, forcing funds to break the buck, which in turn could have led to more investor flight from MMMFs. The Fed was able to act more quickly than Treasury to respond to the evolving difficulties of MMMFs when speed was critical. Rather than transacting directly with MMMFs, the Fed offered loans to banks, which they could use to purchase asset-backed commercial paper from MMMFs.

On September 29, Treasury introduced a more dramatic program that will insure the value of MMMFs. The program was structured essentially as a form of deposit insurance. Participating funds would pay an upfront fee of one basis point for an initial three-month coverage period that could be extended to a maximum of one year at the discretion of Treasury. Mutual funds joining the program include industry giants Vanguard and Fidelity. In some respects, this guarantee program reflects an acknowledgment that for many individual investors MMMFs perform a function similar to savings accounts that are covered under the FDIC.

Clearly neither the AMLF nor the Fed's guarantee of MMMF deposits has proven adequate. Due to continuing investor redemptions from MMMFs, as well as continued illiquidity in credit markets, on October 21 the Fed introduced the Money Market Investor Funding Facility (MMIFF) to facilitate the purchase of commercial paper, certificates of deposit, and banknotes issued by certain financial institutions from MMMFs. The facility is designed both to create a market for short-term instruments held by MMMFs such that they can liquidate positions to meet redemption requests. Private-sector special purpose vehicles (PSPVs) may be created with a mandate to purchase short-term instruments from 10 designated financial institutions, subject to top short-term credit ratings and outstanding debt maturity of no more than 90 days. The purchases will be 90% funded by a loan from the Fed's new MMIFF and 10% funded by the PSPV issuing its own asset-backed commercial paper.

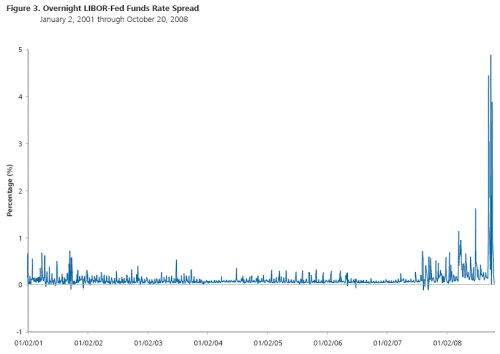

Swap Lines

The Fed has also sought to alleviate illiquidity in dollar lending markets overseas via swap lines with foreign central banks. By providing dollars to foreign central banks, the Fed enables those foreign banks to supply dollar liquidity to their domestic banks, thereby limiting the impact of the US credit crunch on foreign banks and financial markets. Because of the global nature of modern banking, the Fed is concerned with global liquidity. Non-US banks typically perform a substantial number of transactions, including lending, in US dollars as the dollar is the leading currency for cross-border trade and finance transactions. As such, the US dollar is the primary currency for international interbank lending. Foreign banks have not been spared by the recent sharp contraction in interbank lending among US banks, as banks have become concerned about their counterparties' balance sheets and capacity to repay loans of one day or a few days in maturity. Government rescues of major European banks, such as Fortis and RBS, have underpinned the concern that counterparty risks are not limited to US banks. The effective price of global interbank lending in dollars is measured in the daily LIBOR quote. Although overnight LIBOR has historically stayed well within one percentage point of the fed funds rate, the differential has been volatile in recent weeks, sometimes reaching more than 4%—400 basis points.

Swap lines between central banks represent a pre-commitment to do a foreign exchange swap up to the size of the swap line. For example, under a swap line between the Fed and the Bank of England, the Fed would give the Bank of England US dollars in exchange for pounds sterling at the current spot exchange rate with an agreement to reverse the transaction on a pre-determined date and at a pre-determined exchange rate, often the same rate.17 Conducting the two legs of the transaction at the same rate eliminates an exposure to exchange rate changes during the swap period.

Historically, swap lines existed to help one central bank defend its currency by allowing the bank quick but short-term access to additional foreign exchange reserves. In this era of floating interest rates, swap lines have become a less frequently used policy tool. Since the Euro was introduced in 1999, the Fed had maintained swap lines only with Canada and Mexico.18

On December 12, 2007, the Fed began extending swap lines, starting by initiating lines to the ECB and Swiss National Bank for $20 billion and $4 billion respectively, as a means to provide dollar credit to banks in the euro zone and Switzerland. After increases in the ECB and Swiss swaps in March and May, on September 18, the Fed began rapidly adding lines to additional central banks and expanding existing lines. On October 13 and 14, 2008, the Fed agreed to unlimited swap lines with the ECB, Bank of Japan, Bank of England, and Swiss National Bank. The goal of unlimited swap lines is similar to that of unlimited deposit insurance in preventing bank runs: to calm banks about lending to one another, a tactic which, if successful, will mean the swap lines will not need to be used. In addition, swap lines are now in place with the Bank of Canada, Bank of Australia, Sveriges Riksbank (Sweden), Danmarks Nationalbank (Denmark), and Norges Bank (Norway).

If More Ammunition Is Needed: Prospective Policies

If further policies are needed, it seems likely that the next step would be housing market relief in order to address the current crisis at its source. A sharp decline in housing markets would typically not qualify for government intervention. However, some economists argue that the current economic problems cannot be addressed without stemming what they see as a vicious cycle in housing prices and foreclosures: as long as housing prices continue to fall, more households will have negative equity in their homes and more owners will walk away from their mortgages. The resulting foreclosures will drive housing prices yet lower. Academic economists have put forth several competing proposals for housing market-level reform, all of which involve some form of mortgage refinancing by the government to 30-year loans at lower interest rates. Some proposals call for writedowns of mortgages that exceed the current value of the home. Our October 10, 2008 paper discusses these proposals in more detail.

Mortgage refinancing proposals could substitute for the government's purchases of mortgage-related assets planned under the TARP, at least in part. If mortgages are refinanced, then the mortgage-backed securities that hold them would immediately be revalued. Consider first a security wholly backed by mortgages, none underwater. If all underlying mortgages are refinanced and any writedown taken by the federal government, then all future cash flows would be received immediately. The value of the security would rise to par or, depending on its terms, all cash flows may be immediately paid and the security would immediately amortize. For a security such as a CDO with a mix of mortgage and other collateral, the security would be revalued to reflect full payment on the mortgage component. This would not fully revalue the securities, in that delinquencies on auto loan, credit card, and other consumer debt have also risen. However, it would address the largest and most troubled component of mortgage- and asset-backed securities. The impact on whole loans held by originating banks would be similar.

Looking Forward

The Treasury and Federal Reserve may continue to introduce new policies designed to calm financial markets and alleviate obstacles to their orderly functioning, although it seems unlikely that policy changes will continue at the same rapid pace seen in the five weeks since Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy. In response to the increasing aid to the financial sector, calls for housing market relief are growing louder, including support from FDIC head Sheila Bair. The presidential election, now two weeks away, may also influence policy decisions. In such extraordinary times, it does not seem implausible that the President-elect and his Treasury Secretary nominee—candidates include current Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson—may be granted a voice in the policy debate even before the inauguration.

We will continue to offer updates as events warrant.

Footnotes

*NERA economists do not specifically endorse any of the policy proposals discussed in this paper. Instead, we describe the proposals and what their proponents believe they would accomplish.

1. The authors gratefully thank Matthew Gulker, Jidong Huang, Ashley Hartman, and Max Kapustin for their assistance.

2. When discounted at an appropriate discount rate. This is how many economists have understood Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke's reference to hold-to-maturity values.

3. Curry, Timothy and Shibut, Lynn, "The Cost of the Savings and Loan Crisis: Truth and Consequences," FDIC Banking Review, volume 13, no.2, December 2000.

4. Caprio, Gerard and Klingebiel, Daniela, 2003. Episodes of Systemic and Borderline Financial Crises. World Bank database.

5. See, for example. Hoggarth, Glenn, Reis, Ricardo, and Saporta, Victoria, 2002. "Costs of banking system instability: Some empirical evidence." Journal of Banking and Finance, 26, pp. 825 - 855.

6. Many economists have noted the many similarities shared by banking crises. For one textbook discussion, see Mishkin, Frederick, The Economics of Money, Banking, and Financial Markets, 7th ed., 2003. Dr. Mishkin was a Governor of the Fed until the end of August 2008.

7. See, for example, International Monetary Fund, Managing Systemic Banking Crises, 2003.

8. See, for example, Hoggarth, G, Reidhill, J., and Sinclair, P., "Resolution of Banking Crises: A Review." Financial Stability Review, December 2003. Diagram 1 in this article is close to a diagram of the approach taken by US policymakers. Also see International Monetary Fund, Managing Systemic Banking Crises, 2003.

9. See, for example, Lumpkin, S., 2002. "Experiences with the Resolution of Weak Financial Institutions in the OECD Area," Financial Market Trends, (82), 107-149. OECD, Paris.

10. Including as four actions (1) the exception to the normal 30-day notice period for Wells Fargo's acquisition of Wachovia; (2) the notice period exception for Mitsubishi UFJ's acquisition of a 24.9% stake in Morgan Stanley; and (3) the notice period exception for Goldman Sachs's and Morgan Stanley's applications to become bank holding companies; (4) in consultation with the Department of Justice, the exception to the five-day antitrust waiting period for Goldman Sachs's and Morgan Stanley's applications.

11. The federal funds rate is the rate at which US banks lend to each other in the overnight market. This is technically a market rate, but the Fed's ability to control liquidity in this market means that the rate normally stays very close to the Fed's target. The discount rate is the rate at which the Fed loans funds to banks.

12. In this context, "Agency" refers to Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae.

13. "The loan is collateralized by all the assets of AIG, and of its primary non-regulated subsidiaries," Federal Reserve Board press release, September 16, 2008.

14. The original 1932 wording of the Section was quite restrictive as to the kinds of collateral allowed for such borrowing. These restrictions limited the borrowing under the Section even during the Depression: total lending under the Section during the Depression was less than $1.5 million. The Federal Reserve Act was amended in 1991 as part of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act to the current wording that allows any sort of collateral found acceptable by the Fed. See Todd, Walker F., "FDICIA's Emergency Liquidity Provisions," Economic Review (3Q1993), Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, for details and discussion.

15. Small, David H. and Clouse, James, "The Scope of Monetary Policy Actions Authorized Under the Federal Reserve Act," B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics, Vol. 5(1), 2005.

16. AMLF is an acronym for the Asset Backed Corporate Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility. One understands the Fed's reluctance to label it the ABCPMMMFLF.

17. Humpage, Owen F. and Shenk, Michael, "Swap Lines," October 9, 2008 as found at http://www.clevelandfed.org/research/trends/2008/1008/01intmar.cfm.

18. Ibid.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.