- within Litigation, Mediation & Arbitration, Technology and Antitrust/Competition Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Technology industries

INTRODUCTION

For a number of years, NERA has been providing statistical predictions of settlements in securities class actions.1 Some of the important determinants of expected settlements that our statistical analysis has uncovered in the past have been described in earlier publications.2 This paper introduces a powerful new tool for understanding expected settlement values for securities class actions: dynamic litigation analysis. This model allows for statistical forecasting of settlement amounts that change as the litigation process moves forward, providing internally consistent predictions. It allows for what-if analysis, answering questions such as, "How much more would this case be expected to settle for if the motion to dismiss were to be denied by the court?" To the best of our knowledge, this is the first model ever built with these capabilities. Below, we describe the model, discuss some of the important drivers of expected settlement values, and provide some illustrations of how the model works.

WHAT CAN THE MODEL DO?

The model allows us to answer a range of new questions, and provides a new perspective on the same type of predicted settlements we have used in the past. Some of the questions that can be addressed include:

- What is the expected settlement value for a case immediately after it is filed, based on the likelihood of the case moving forward in different ways?

- What is the expected settlement value of a case if is settled immediately, at the current status of the litigation?

- What is the expected settlement value after different motions are filed and decisions are reached?

- What would the expected settlement value of the case be if the motion to dismiss were to be denied by the court?

- What would the expected settlement value be if the motion to dismiss were granted, but under appeal?

Because the model is constructed as an integrated whole, the answers to all of these questions, as well as other hypotheticals, are consistent with each other.

As an illustration of the possible use of the model, we provide an example of how predictions might change for one specific case.3 For this particular case, when newly-filed, the model gives a predicted settlement value of $70 million. The model then allows us to forecast the ultimate settlement values that would occur given different outcomes of motions in the case. For example, in this case, the predicted probability of reaching a settlement with the motion to dismiss denied and a motion for class certification filed is estimated to be 55%. This probability is based on the typical progress of cases that are statistically similar, though naturally every case has unique fact patterns that are difficult to measure. When a motion to dismiss has been filed, the predicted settlement can be revised. In this case, the predicted settlement rises by an insignificant amount—this is largely because most cases have historically had such a motion filed. If a motion for class certification is filed, then the predicted settlement rises to $79 million. If the motion to dismiss is then granted, the predicted settlement falls dramatically, to $39 million. These different predictions could either be produced as revisions during the evolution of the case, or could be evaluated as what-if scenarios when developing settlement strategies.

We present several important caveats and interpretive issues concerning these types of forecasts when we discuss the details of the how the model works below. While there are some important limitations, dynamic litigation analysis is a powerful tool that we expect to prove useful in many situations.

DATA

NERA has been collecting data on securities class actions for more than 20 years. In recent years, NERA's predicted settlement models have been estimated using information on settled cases that were filed after the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA) was enacted in December 1995. The new model discussed in this paper uses data on 762 cases filed in 2000 or after, and settled through 30 June 2012. There is a tradeoff between the additional statistical power that can be gained through a larger sample size and the possible introduction of noise by the inclusion of older cases when the litigation environment is changing. As case and statute law have changed over time, older cases may provide little information relevant to cases being litigated today. We have chosen the 2000 filing cut-off in an attempt to balance these two considerations; it maintains a sample size that allows detailed statistical modeling, but focuses on more recent cases.4

As a recent addition to our securities class-actions database, we coded the status of three important motions at the time that settlement occurred for each case. These are the motion to dismiss, the motion for class certification and motions for summary judgment.5 We coded a range of possible ligation developments at the time of settlement for each of these motions.

For example, with a motion to dismiss, the status of the motion could include: motion denied with or without prejudice, motion granted in part, motion granted in full, motion voluntarily denied, or the possibility that no motion had been filed at the time of settlement. In whichever case, only the status at the time of settlement was recorded. For example, our sample of 762 settlements contains 34 cases in which the case was settled, but for which a motion to dismiss had been granted in its entirety, a fact that may seem surprising, since defendants are paying money on a case that has already been dismissed. However, what is happening in these matters is that either the decision is under appeal or parties believe that the case could be successfully refiled in some form. As another example, if a motion to dismiss had been granted, but then successfully appealed, it is coded as having the motion to dismiss denied—the status at the time of settlement. Thus, for the remainder of this paper, when "motion status" is mentioned, we will always be referring to the final status, at the time of settlement.

Some of the combinations of motions status may seem surprising, but virtually every possible combination is represented in the database. For example, in our database, nearly 10% of cases settle before a motion to dismiss is filed. Also, though the typical sequence is that a motion to dismiss is filed and then defendants file a motion for class certification, there are least two settled cases for which a motion for class certification was filed, but no motion to dismiss was.

MODELING

The modeling approach

Although a particular case might settle at any point in the litigation process—before a motion to dismiss is filed or after class certification, for example—it ultimately only settles at one point. As such, we do not know with certainty what that case might have settled for had it settled at some other point. This creates some complexity in the statistical modeling required to predict internally consistent settlement values at different points in the litigation process. The approach we have taken is to first construct a statistical model of expected settlement values for cases conditional on knowing the stage of litigation at time of settlement and then construct additional models that allow us to predict the probabilities of settling at different points. These models are then combined to construct the full dynamic litigation model. As the preceding description is somewhat abstract, we hope that the detail provided below will lead to more clarity.

The first step in the approach is to construct a statistical model that predicts the expected value of settlements, conditional on the final status of motions in the case and conditional on other variables that we have found to have significant predictive power for settlement values. That model is a standard linear regression model.6 We refer to this as the "fully conditional model" because it uses the final status of motions as predictors, even though these will not be known until the case actually settles. The fully conditional model explains more than 70% of the variation in settlement values.7 For the historical cases that we use to estimate the model, the final status of motions is known, allowing the model to be estimated using standard statistical techniques.

Drivers of expected settlements in the fully conditional model

In this section we discuss the factors that drive expected settlements, conditional on knowing the stage of litigation at which the case settles. We will discuss the impact of the stage of litigation first, because that is the most important innovation in the present model. Note that the impact on expected settlement of some of the variables will be different at different stages of the litigation. In one specific case we will discuss the differences, but there are too many different drivers of expected settlements to discuss all of them in detail. When we discuss the impact of any individual variable, including the status of litigation variables, these impacts are conditional on the effects of all the other important drivers of expected settlements. That is to say, all of our analysis looks at all of the variables simultaneously affecting settlements and considers the impact of changing one, while holding constant the values of all of the others.

The effect of stage of litigation on expected settlement value

As discussed above, we coded data on the status of motions to dismiss, to certify the class, and for summary judgment. We found significant impacts of the status of the motion to dismiss and the motion for class certification, and these are discussed in detail below. However, we could find no statistically reliable link between expected settlements and the status of motions for summary judgment. This is likely the result of the relatively small number of cases in which such motions were actually filed—only 79 of the cases in our dataset had motions for summary judgment. Further, this relatively small number of cases included motions from both sides of the litigation and several different possible outcomes.

There is an important caveat to the interpretation of any of the effects of motion status that we report here: all of the effects are on expected settlements if a case settles at all. When defendants file a motion to dismiss, they are hoping that they will be able to avoid a settlement entirely as the case gets dismissed and stays dismissed. Here, we are capturing only a secondary benefit: the reduction in settlement that arises if there is a settlement at all. Because the present analysis is based only on settled cases, when we speak of "an expected settlement" we are always referring to the expected settlement, if there is any settlement at all.8 This is distinct from the expected dollar payout in a case, which would have to include the cases that resulted in no payout from defendants.

Motion to dismiss

For motions to dismiss, we found that simply having filed a motion to dismiss does not have a statistically significant effect on the expected settlement. As noted above, only about 10% of cases in our sample never had a motion to dismiss filed. These cases do not appear to be unusual in terms of their settlements, conditional on the other drivers of settlements discussed below.

However, the outcome of a motion to dismiss does have a significant effect on expected settlements. Unsurprisingly, cases that settle after a motion to dismiss has been granted in its entirety settle for much lower values. While the expected effect varies with the specific facts of the case, on average cases settling after a motion to dismiss has been granted settle for more than 40% lower values than they would otherwise. This is the effect relative to a group of other outcomes that includes cases in which no motion to dismiss was filed, cases in which the motion was filed but that had no resolution before settlement and cases in which the motion was voluntarily withdrawn. The different outcomes within that group did not have statistically reliably different effects on expected settlements, which is why they were grouped together.

By contrast, when a motion to dismiss is denied, the expected settlement rises, as one would expect. Cases where the motion was denied with or without prejudice or was granted in part, all have statistically similar outcomes. Examination of the settlements for which the motion to dismiss was granted in part shows that in most of these cases the motion was granted for some particular defendants or with respect to only some securities. This does not appear to significantly affect the aggregate settlement.

The expected impact of having a motion to dismiss denied is not uniform across cases. In particular, the cases with larger potential alleged losses to investors have a larger percentage increase in expected settlement if the motion to dismiss has been denied. For the very smallest cases, the effect of a denial of the motion to dismiss is relatively minor—even in percentage terms. We measure the size of potential alleged losses by a factor called "investor losses." This is a proxy for the aggregate amount that investors lost from buying the defendant's stock during the class period relative to investing in the broader market; it is also a rough proxy for the relative size of plaintiffs' potential claims. "Investor losses" is the single most powerful predictor of expected settlements. Loosely speaking, a big case is one with large investor losses. So we can paraphrase the results above by saying that, for big cases, having a motion to dismiss denied has a larger proportional impact than for small cases. For a case with a typical level of investor losses, the effect of having a motion to dismiss denied is only about 10%, but effects are much larger for bigger cases. Again, these figures do not include the fact that having the motion to dismiss denied may remove an opportunity for the defendants to have the case go away entirely.

Motion for class certification

We now turn to the motion for class certification. We did not find reliable statistical relationships between the resolution of a motion for class certification and expected settlements. However, we did find that the mere existence of a filed motion for class certification leads to a higher expected settlement, with an increase of about one-third as compared to cases that settled before a motion had been filed. This result needs a little explanation, as the filing of a motion for class certification is an act on the part of plaintiffs and not any sort of decision by a court. The issue here is that when we measure the status of motions at the time of settlement, there are two different factors; outcomes in the courts on the one hand, and strategic decisions on the part of defendants and plaintiffs as to when, and whether, to settle, on the other hand. These strategic decisions will generally depend on characteristics of cases that cannot be measured fully, such as the nature and strengths of the allegations made. The time at which a case settles may reveal information about the strengths of the case. In the situation at hand, in which a motion for class certification has been filed, plaintiffs have revealed that they believe it is worth their time and effort to put in the work to file the motion, rather than settling immediately. Such cases may have stronger facts, or more potential jury-appeal, on average.

All of the results above for motions to dismiss should be taken in the same context. While the results there are intuitive, there may be some effect on the magnitudes as a result of selection: cases that make it to a resolution on the motion to dismiss may be different in some immeasurable ways from other cases that settle before that point.

One more consideration is important for understanding the magnitude of these effects. Because these are the results in the fully conditional model, which looks at settlements as they are completed, they will not generally represent the impact of, for example, moving from not having a filed motion for class certification, to having one. Rather, they compare expected values across different cases. To answer questions about the evolution of specific cases, we need to use the complete dynamic litigation model that combines the fully conditional model with models for the probabilities of different outcomes.

Other drivers of expected settlement values

We have investigated the effects of many possible drivers of settlement values. Here we discuss the impact of those that we have found to be robustly statistically related to expected settlement values.

The most important of these is our investor loss measure, which has been described above. While investor losses constitute a critical predictor of expected settlements, expected settlements do not rise one-for-one with investor losses. Instead, as investor losses rise, expected settlements rise much more slowly: a 1% increase in investor losses is associated with an approximately 0.25% increase in the expected settlement. This is for a matter in which the motion to dismiss has not been denied. As discussed above, in the alternative the effect of increasing investor losses is larger. As will be discussed below, the effect of increasing investor losses is also larger for some matters that have a lead plaintiff that is a public pension plan.

Settlements also increase with the potential depth of defendants' pockets. If the defendant company's market capitalization on the day after the end of the class period is larger, the settlement is expected to be higher. Cases with an accounting firm as a co-defendant are associated with settlements that are larger than cases without such a co-defendant and the effect is quite large. Because we measure settlements as the total paid by all defendants, this may reflect in part the extra ability to pay on the part of the accounting co-defendant.

There are some observable factors that may be related to the strength of potential allegations against the defendant. If the defendant company has admitted to accounting irregularities related to the allegations in the complaint, the settlement is expected to be larger. Also, if a company or any of its employees was convicted of or plead guilty to a crime directly related to the allegations in the complaint, or was required to make a payment to a government agency, again for reasons related to the allegation in the complaint, the settlement is higher on average. Further, if a company has restated its financials at any time during the class period, for reasons relevant to the issues raised in the complaint, then expected settlement is higher. Finally, if there is a parallel derivative action, then the settlement is generally higher.9

If securities other than common stock are also involved in a settlement, the expected payment rises. Because our measure of investor losses is based on common stock only, losses claimed by investors in other securities may drive up settlements. The effect of bonds sharing in a settlement is larger than that of options or preferred stock. This is likely because the outstanding volumes of bonds are usually larger than of other securities.

Cases with an institutional investor serving as lead plaintiff settle for more than settlements without such an institutional lead plaintiff, other things equal. The effect is larger if relatively few cases filed in the same year also had institutional lead plaintiffs. Statistically, we cannot reject the hypothesis that if all other cases in a year had institutional lead plaintiffs, then the identity of the lead plaintiff would not matter. This strongly suggests that the resulting higher settlements do not come from the actions of lead plaintiffs in managing case litigation, but rather come from such plaintiffs selecting relatively stronger cases.10 If the lead plaintiff is not only an institution, but is also a public pension fund, then the expected settlement is still larger, at least for cases with large investor losses. For cases with modest investor losses, there is no additional effect. For cases with unusually large investor losses, the expected effect of having a public pension fund as a lead plaintiff can be very large. As with other institutional investor lead plaintiffs, this effect is attenuated if there are a large number of public-pension fund lead plaintiffs among cases filed in the same year.

Settlements increase if violations of Section 11 are alleged, all else equal. Section 11 claims have a lower burden of proof for plaintiffs than do Rule 10b-5 claims, which we would expect to increase settlements relative to pure Rule 10b-5 claims.

Finally, expected settlements are somewhat lower for cases filed in 2003 or after. We have considered all possible years, based on both filing year and settlement year. The break at the 2003 filing year has the greatest statistical explanatory power.

DYNAMIC LITIGATION ANALYSIS

Our analysis of the fully conditional model identified factors relating to the stage of litigation that are important for predicting the ultimate settlement. There are two factors for the motion for class certification, which simply amount to whether one has been filed or not. For the motion to dismiss, it is the outcome of the motion that matters: was it granted, denied, or was there some other outcome, such as a settlement before any decision was reached on the motion. When a case is initially filed, we cannot know with certainty at which stage of its litigation it will settle. But it is possible to build a set of statistical models that will allow us to predict the probabilities of each of the relevant outcomes.11

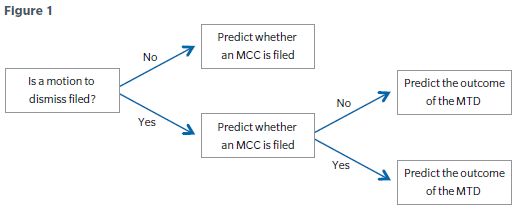

Figure one depicts a simple schematic showing how we have modeled the evolving status of motions in a case. The design of the tree is based on the typical sequence of events in a case.12

This sequence is not the only way to model the evolution of a case in litigation, but it follows the most common sequence: a motion to dismiss (MTD) is filed (or the case is settled first), then a motion for class certification is filed (MCC). Then a decision is reached on the motion to dismiss.

This tree can serve as a guide to constructing a prediction of the expected settlement at each stage of the litigation. At the end of the tree, once we reach the far right-hand side, the end status is known so that a prediction can be made using the fully conditional model that has been described in detail above. At each node of the tree, it is possible to estimate a statistical model that predicts the probabilities of the next movement through the tree. When the predictions from each of these models are combined, they give a forecast of the probabilities of each of the possible final outcomes.

The details of the predictions at each node go beyond the scope of this paper. They are estimated by standard statistical methods known as logit and multinomial logit models.13 These methods allow the inclusion of many different factors to predict the relevant outcomes. We evaluated the statistical significance of each of the factors that is in the fully conditional model to establish the relevance for predicting outcomes at each node.14 In one place in the tree, there are only a few observations, so simple proportions are used rather than a complicated model. The overall forecast that one would construct at each point in the tree depends only on the drivers that have already been described above, but at each stage the importance of the different factors will be somewhat different, although the overall direction of the influence of each factor remains the same.15

One interesting finding connected to the changing importance of the different drivers of predicted settlement values at different stages in the process involves the variable for having admitted to accounting irregularities during the class period. In the fully conditional model, this variable has a smaller impact than it has had in older versions of NERA's predicted settlement models. This is not because the variable has had less impact in more recent cases, but rather because we have included the status of motions variables, and having admitted accounting irregularities is a strong predictor of the status of motions variables. In particular, our modeling shows that it is much more unlikely for a case to settle when the motion to dismiss was granted in a case where accounting irregularities have been admitted. For a newly-filed case, the impact of this factor is similar to that in NERA's previous models. But once a case has already had, for example, the motion to dismiss denied, then the impact of admitting accounting regularities is comparatively smaller.

In essence, the way that the model works is that it constructs a forecast at each node in the tree and then weights those forecasts by the probability of getting to that node. The combined forecast at the left-most node of the tree, the origin point, is then the appropriate forecast for a newly-filed case, where no action has yet been taken by either side of the litigation, apart from filing a complaint. As the case moves through the litigation process, some of the branches of the tree become irrelevant. As that happens, the other branches are reweighted to take that into account, so that at each stage of the litigation the forecasts are consistent with each other.

The exact effect of developments in litigation on the predicted settlement for a case depends on the specific facts of that case. It cannot easily be summarized because of the complexity of the dynamic litigation model. This results from weighting the predicted settlements for each possible combination of final motion status by the estimated probability of each such combination. The example near the beginning of this paper shows how the predicted settlement can be re-estimated as it moves through the litigation process.

NEXT STEPS

Dynamic litigation analysis can provide answers for a range of questions about settlement values that could not be previously answered. However, it does not answer every question one might want to ask about the future of a piece of securities class action litigation. It cannot answer, for instance, the question, "what is the probability that a case will end in a dismissal, with no cash settlement?" It also cannot answer the question of what the expected payout is for a case, but only the expected settlement, conditional on a settlement being reached.

Both of these limitations arise from the underlying database that we are using for estimation: it does not yet contain the full set of variables for cases that are ultimately dismissed with zero settlements. However, NERA is working on coding all of the relevant variables. In the near future, we expect to have a model that will be able to predict the full scope of litigation outcomes.

Footnotes

1 Our prediction models, including the new model discussed here, are primarily for securities class actions in which common stock is alleged to be damaged and that contain Rule 10b-5 and/or Section 11 claims.

2 See, for example, "Recent Trends in Securities Class Actions Litigation: 2009 Mid-Year Update; Filings Remain High, Fueled by Credit Crisis and Ponzi Scheme Claims; Median Settlements Remain Under $10 Million," 27 July 2009, Stephanie Plancich and Svetlana Starykh, NERA working paper.

3 The facts, other than motion status, are taken from a settled case in our database. We then consider a case with the same facts hypothetically moving through the litigation process.

4 More than three-quarters of the 762 cases that we analyzed settled in 2005 or later.

5 The motion to dismiss is filed by defendants, and the motion for class certification is filed by plaintiffs, but the motion for summary judgment may be filed by either party. In the case of the latter motion, we coded separately motions brought by plaintiffs or by defendants.

6 Technically, it is a linear regression model but with the variable to be explained as the natural logarithm of the real (inflation-adjusted) settlement value. For technical reasons, because of the logarithmic transformation an additional adjustment is required when predicting the dollar value of settlements so that the final prediction is unbiased.

7 More precisely, it measures more than 70% of the variation in the natural logarithm of real settlement values.

8 We are currently working on developing the data necessary to look at cases that are ended in one way or another without any settlement.

9 A derivative action is considered to be parallel in this context if the allegations in the derivative action are substantially allegations also contained in the class action.

10 Because we are holding constant other measured characteristics of cases, institutional lead plaintiffs would have to select cases that are stronger along dimensions that we are not measuring for this story to hold true.

11 From a technical point of view, one way to think about this is as an imputation of missing variables when predicting from a regression model. In the fully conditional model, there are variables concerning the status of motions, but these variables are not observed for a newly filed case, because no one knows when the settlement might occur. However, these variables can be consistently predicted using the data on settled cases. This sort of imputation of missing variables is a standard technique in econometric analysis.

12 There is more than one way to design the tree. In small samples, different tree designs will generally lead to different predictions. As sample sizes grow large, the predictions should converge.

13 The logit model allows for the prediction of 0/1 variables, such as," is there a motion to dismiss filed or not? " The multinomial logit model allows predictions where is a small number of possible outcomes, but more than two.

14 We did not evaluate the motion status variables, because it is exactly those variables that we aim to predict.

15 The fact that the overall direction of the impact of each factor remains unchanged is a result from the estimation, not a constraint that was imposed a priori.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.