ABSTRACT

We conduct an empirical inquiry into the effect of the Supreme Court's 2010 Morrison decision, which limited the reach of US securities laws to trades occurring on US markets, on the competitiveness of US markets as a venue for listings by foreign issuers and trading in cross-listed stocks. In the wake of the Morrison decision, the Dodd-Frank Act requires that the SEC inform Congress about the merits of creating a new extraterritorial right of action. We provide input into the debate by using data on 329 shareholder class actions filed against foreign-domiciled companies and discussing the effects of such a right on the competitiveness of U.S. capital markets. We conclude that, following Morrison, foreign companies' expected litigation costs should fall, because investors who purchased their shares on overseas exchanges will be excluded from classes. By reducing expected litigation costs, Morrison eases a deterrent to US listing by foreign issuers and thereby makers the US a more competitive venue for cross-listings, as well as for the volume in cross-listed stocks.

I. INTRODUCTION

Congress will soon consider whether to legislate an extraterritorial private right of action under Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 ("Exchange Act") that US courts had recognized for decades. In June 2010, the Supreme Court ruled in Morrison v. National Australia Bank that only trades on US markets are covered under the Exchange Act.1 For decades, US courts had heard securities cases under Section 10(b) against foreign issuers, beginning with Schoenbaum v. Firstbrook in 1968.2 Courts had defined tests to determine which purchases would be covered based on whether the investors were American, whether they bought their shares on US markets, and whether and which fraudulent acts had occurred in the US. The Supreme Court nullified these tests on grounds that no US law applies outside the US borders unless the law gives a clear indication that it is intended to apply extraterritorially.3 In the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act ("Dodd-Frank"), Congress took two actions partially reversing the impact of the Morrison decision via legislation. Congress immediately restored the ability of the government and the Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC") to bring cases under Section 10(b) involving transnational securities fraud. In addition, Congress directed the SEC to study the merits of creating a new extraterritorial private right of action.

This paper provides input into the debate on the merits of creating a new private right of action by reviewing the 329 shareholder class actions filed against foreign-domiciled companies and discussing the effects of such a right on the competitiveness of US capital markets. We focus on Rule 10b-5 shareholder class actions against foreign issuers, which we define to involve suits against a foreign issuer whose stock trades on US markets, on behalf of a plaintiff class that includes both investors who purchased their securities on US markets and investors who purchased their securities overseas.4,5 We conclude that, following Morrison, foreign companies' expected litigation costs should fall, because investors who purchased their shares on overseas exchanges will be excluded from classes, driving down damages and settlements. By reducing expected litigation costs, Morrison eases a deterrent to US listing by foreign issuers and thereby makes the US a more competitive venue for cross-listings, as well as for the volume in cross-listed stocks.

II. FILINGS AGAINST NON-US COMPANIES IN US COURTS

US courts have been an attractive venue for plaintiffs to file shareholder class actions, even against companies domiciled in foreign countries. Although other countries have recently created a legal framework for class action litigation, including Australia, Canada and Italy, long standing and well-defined class action rules in the US make it a uniquely well-suited venue for this type of litigation.6 Participating in a class action is essentially a free call option to plaintiffs, removing any downside financial risk as well as the need for plaintiffs to coordinate to fund litigation. US law allows for contingency fee arrangements, where plaintiffs' attorneys fund the litigation and receive a percentage of any damages or settlement. Furthermore, the US does not have the fee-shifting rules common in other countries that require the losing side to pay some or all of the winner's legal fees. As a result, plaintiffs incur no legal expenses to enter litigation and minimal, if any, financial risk. Lead plaintiffs will invest only time in participating and supervising litigation, and there is no cost whatsoever to other class members. Finally, the jury trial system in the US increases the probability of large verdicts against defendant corporations, should cases go to trial.7

For these reasons, plaintiffs and their attorneys have substantial incentives to file shareholder class actions in the US. Without restrictions on access to US courts, suits might be filed in response to disclosure of fraud against companies from around the world, even without a US listing, provided they involved substantial market capitalization, a large price drop, and good record keeping of stock ownership.

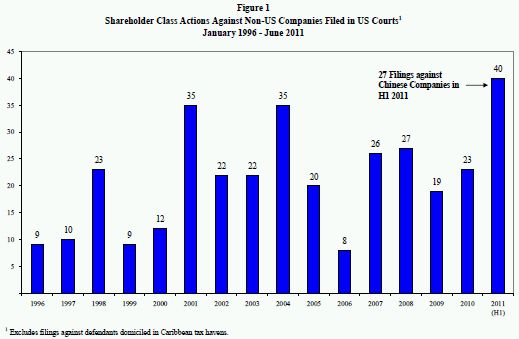

Plaintiffs have regularly filed shareholder class actions against non-US companies in US courts, and the rate of filing shows no sign of declining subsequent to the Morrison decision in 2010. Figure 1 reports filings against non-US companies by year, from 1996 through June 2011. While the number of filings has fluctuated from year to year, at least 19 actions have been filed against non-US companies in every year since 2007. The dramatic increase in filings in 2011 is primarily driven by a wave of actions filed against Chinese companies. Of 40 actions against non-US companies filed in the first half of 2011, 27 were against Chinese companies, all of which listed their stock only in the US. However, even excluding these cases, it is clear that filings against foreign companies have not decreased since the Morrison decision in June 2010.

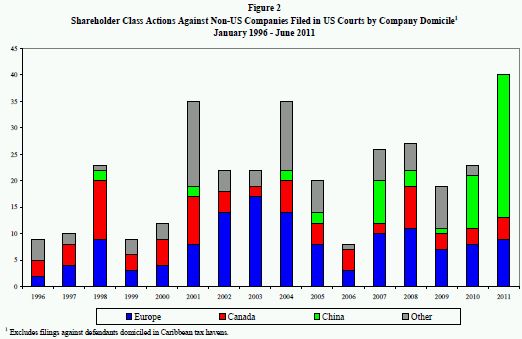

Historically, companies domiciled in Europe and Canada have accounted for the majority of filings against non-US companies. Figure 2 reports annual filings by the defendant company's country or region. Prior to 2010, companies domiciled in Europe and Canada accounted for at least 50% of all filings against non-US companies: Canadian firms faced more filings than those from any other country until 2007. While filings against Chinese companies have increased since 2010, filings against European and Canadian firms have remained within historical ranges.

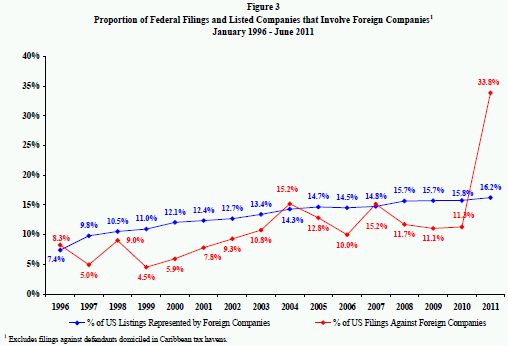

In most years since 1996, foreign companies listing in the US have faced lower odds of a shareholder class action than domestic companies. As Figure 3 shows, in all but four years, foreign companies accounted for a greater percentage of US listings than class action filings. The greatest outlier, by far, is the first half of 2011, which is driven primarily by the large number of suits against Chinese firms filed this year. Excluding these 27 filings, foreign firms would account for 13.1% of filings in the first half of 2011.

III. INCLUSION OF F3 INVESTORS

Prior to the Supreme Court's decision in Morrison, courts ruled on a case-by-case basis on whether to include so-called foreign-cubed investors ("F3"), foreign investors who purchased shares of a foreign-domiciled company on a foreign market, in a class. These rulings followed a common framework, in which courts could decide whether to exclude F3 investors at two separate stages of the litigation. First, courts determined whether they had subject matter jurisdiction over trades made by F3 investors. Through a series of decisions, the courts had articulated two tests, the conduct test and the effects test, that were required to be satisfied to create jurisdiction. Second, F3 investors could be excluded at the class certification stage, where the primary issue was whether courts in foreign plaintiffs' home countries would hear litigation of the same claims following a US resolution.8

This section begins by discussing the number of cases filed against non-US companies in which F3 investors were included in the initial class. Next, we discuss courts' standards for determining whether subject matter jurisdiction exists over trades made by F3 investors, and report statistics on the number of instances where F3 investors have been allowed or excluded based on these tests. Finally, we discuss class certification, and provide statistics on F3 investors' inclusion or exclusion at this stage of litigation.

A. Filings Including F3 investors

Not all shareholder class actions against non-US companies involve F3 investors. First, some defendant companies trade only in US markets, and therefore do not involve investors purchasing in foreign markets. Second, even in some cases where defendant companies are traded on multiple markets, plaintiffs choose to file actions solely on behalf of investors purchasing shares or ADRs on US markets.

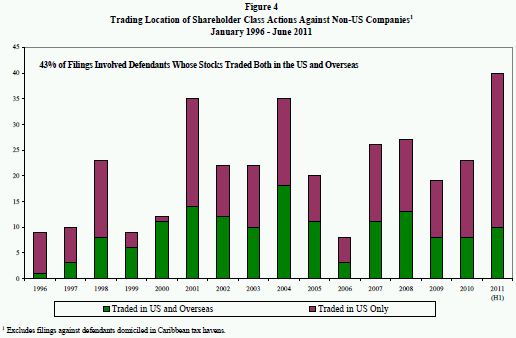

Figure 4 reports filings by year against defendant companies traded on multiple markets and those traded only in the US. Of 340 total filings, 147 (43%) were against companies listed on both US and foreign exchanges. All 27 Chinese firms that were defendants in actions filed in the first half of 2011 traded only on US markets, causing the proportion of dual-listed firms in 2011 to be below that of previous years. All 27 Chinese companies had listed via reverse mergers, enabling them to avoid the level of regulatory scrutiny required for an IPO; the subsequent class actions all raise accounting allegations.

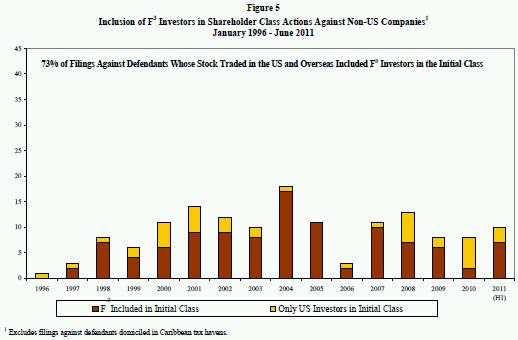

Figure 5 reports the number of filings against those companies traded on multiple markets, and whether plaintiffs filed on behalf of all investors (including purchasers on foreign exchanges) or only US investors. Of 147 total filings against dual-listed defendants, 107 (73%) included purchasers on all exchanges (and therefore F3 investors) in the proposed class in the complaint.

B. Subject Matter Jurisdiction

Prior to Morrison, courts decided whether subject matter jurisdiction existed over trades by F3 investors on a case-by-case basis. Decisions on subject matter jurisdiction were based on the application of two tests, the conduct test and the effects test, and satisfaction of either test resulted in a finding of subject matter jurisdiction over the trades of a given class of plaintiffs.

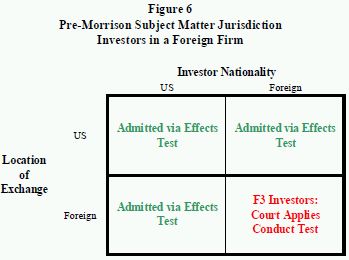

The diagram below shows the typical pre-Morrison framework for subject matter jurisdiction over trades by investors in a foreign firm. As explained in more detail below, investors satisfied the effects test if they were either residents of the US, or purchased on a US market. Because they were neither residents nor purchased in the US, F3 investors did not satisfy the effects test, and decisions regarding subject matter jurisdiction were made on a case-by-case basis based on the conduct test.

Satisfaction of the effects test depends on whether the defendant's allegedly fraudulent conduct directly affected US investors or markets. The test was first articulated in Schoenbaum v. Firstbrook (1968), an action brought against a Canadian corporation by a US shareholder.9 The court found that,

Congress intended the Exchange Act to have extraterritorial application in order to protect domestic investors who have purchased foreign securities on American exchanges and to protect the domestic securities market from the effects of improper foreign transactions in American securities.10

Courts typically found that investors living in the US, or purchasing shares on US markets, therefore satisfied the effects test, while finding that F3 investors failed to meet its requirements.11

Courts therefore turned to the conduct test to establish the extent of subject matter jurisdiction over F3 investors.12 Satisfaction of the conduct test depends on whether the alleged fraudulent conduct took place within the US. The test was first articulated in Leasco v. Maxwell, in which the Second Circuit found that the test was satisfied in the case of fraud committed in the US that induced a US investor to purchase securities in London.13 However, in IIT v. Vencap, Ltd. (1975), the Second Circuit found that the conduct test was satisfied even if investors were not based in the US, stating, "[W]e do not think Congress intended to allow the United States to be used as a base for manufacturing fraudulent security devices for export, even when these are peddled only to foreigners."14

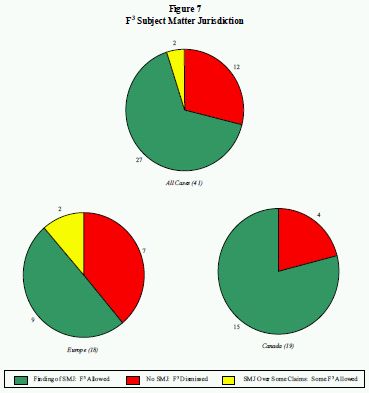

As the conduct test evolved, different circuits developed notably different standards for when the conduct test was satisfied. The D.C. Circuit has adopted the most stringent standard, finding that the test was satisfied only if all factors required by Section 10(b) of the Securities and Exchange Act were committed in the US.15 In contrast, the Second, Fifth and Seventh Circuits required that acts "more than merely preparatory conduct to the fraud" took place in the US and that the US conduct caused the foreign plaintiffs' loss.16 The Third, Eighth and Ninth Circuits adopted the least stringent standard, requiring only that some conduct designed to further the fraudulent scheme occurred in the US.17 Figure 6 reports the number of instances, both overall and by region, in which US courts found subject matter jurisdiction over F3 investors. Of 107 filings including F3 investors in the initial class, 41 reached a point where the court decided on subject matter jurisdiction over trading by F3 investors.18 In 27 of 41 cases (66%), courts found that subject matter jurisdiction existed over F3 investors' trades. Courts were more likely to find subject matter jurisdiction over trading by F3 investors in cases involving Canadian defendant firms, with findings favorable to F3 plaintiffs in 15 of 19 cases (79%) versus 9 of 18 cases (50%) for defendants domiciled in Europe.

C. Class Certification

Beyond the normal class certification issues, the certification of classes including F3 investors depends primarily on whether courts in foreign plaintiffs' home countries would hear litigation of the same claims following a US resolution. Courts historically excluded F3 investors from classes when they found that there was a "near certainty" that courts in plaintiffs' home countries would fail to recognize a judgment or settlement in US courts, with the "near certainty" standard first articulated in Bersch (1975).19 In a 2007 decision in Vivendi, however, the Southern District of New York revisited the standard put forward in Bersch, and found instead that F3 investors should be excluded if it is "more likely than not" that the relevant foreign court would fail to recognize the US outcome.20 The Vivendi court evaluated the claims of F3 investors on a country-by-country basis, allowing investors from England, the Netherlands and France to remain in the class, while excluding investors from Germany and Austria.

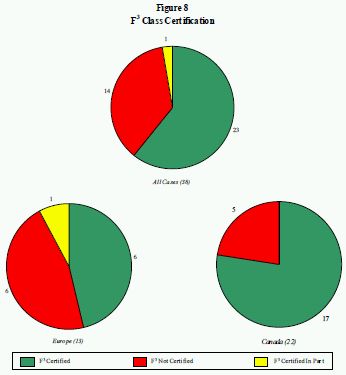

Figure 7 reports the number of instances, both overall and by region, in which US courts certified classes including F3 investors. Of 107 filings including F3 investors in the initial class, 38 reached a point where the court ruled on class certification.21 In 23 of 38 cases (61%), courts included F3 investors in the certified class. Courts were more likely to certify F3 investors as class members in cases involving Canadian defendant firms, with findings favorable to F3 plaintiffs in 17 of 22 cases (77%) versus 6 of 13 cases (46%) for defendants domiciled in Europe.

To read this Working Paper in full, please click here.

Footnotes

* Elaine Buckberg is Senior Vice President and Max Gulker is Senior Consultant at NERA Economic Consulting. The authors thank Chyhe Becker, Timothy Helwick, Daniel Kramer, David Tabak and participants in a seminar at the Securities and Exchange Commission for insightful comments; Svetlana Starykh for assistance with NERA's Class Action Database; and Gary Wu, Tyler Wood and Grace Kaminer for superb research assistance. All errors, omissions and other issues are the authors' alone.

1 Morrison v. National Australia Bank Ltd., 130 S. Ct. 2869, 2884 (2010).

2 Buxbaum, Hannah, "Multinational Class Actions Under Federal Securities Law: Managing Jurisdictional Conflict," Columbia Journal of Transnational Law, Volume 46, Issue 1, June 2007, p. 21.

3 Morrison v. National Australia Bank Ltd., 130 S. Ct. 2878 (2010).

4 Since PSLRA, all Rule 10b-5 securities class actions brought against foreign issuers involved stocks that traded on US markets, whether on an exchange or over the counter ("OTC"); many of these stocks also traded overseas, in some cases with the overwhelming majority of the volume trading outside the US. NERA Securities Class Action Database.

5 The Morrison decision describes broad acceptance that the Exchange Act applied only to stocks traded on US exchanges: "The primacy of the domestic exchange is suggested by the very prologue of the Exchange Act, which sets forth as its object '[t]o provide for the regulation of securities exchanges . . . operating in interstate and foreign commerce and through the mails, to prevent inequitable and unfair practices on such exchanges . . . .' 48 Stat. 881. We know of no one who thought that the Act was intended to 'regulat[e]' foreign securities exchanges—or indeed who even believed that under established principles of international law Congress had the power to do so. The Act's registration requirements apply only to securities listed on national securities exchanges. 15 U. S. C. §78l(a)." Morrison v. National Australia Bank Ltd., 130 S. Ct. 2874 (2010).

6 Gassman, Gary and Perry Granof, "Global Issues Affecting Securities Claims at the Beginning of the Twenty- First Century," Tort Trial & Insurance Practice Law Journal, Fall 2007 (43:1), pp. 85-111.

7 Grant, Stuart and Diane Zilka, "The Role of Foreign Investors in Federal Securities Class Actions," Securities Litigation and Enforcement Institute 2004, Corporate Law and Practice, Course Handbook Series Number B- 1442.

8 Bersch v. Drexel Firestone, Inc., 519 F.2d 974, 996 (2d Cir. 1975).

9 Buxbaum, Hannah, "Multinational Class Actions Under Federal Securities Law: Managing Jurisdictional Conflict," Columbia Journal of Transnational Law, Volume 46, Issue 1, June 2007, p. 21.

10 Schoenbaum v. Firstbrook 405 F.2d 215 (2d. Cir. 1968) at 206.

11 Buxbaum, Hannah, "Multinational Class Actions Under Federal Securities Law: Managing Jurisdictional Conflict," Columbia Journal of Transnational Law, Volume 46, Issue 1, June 2007, pp. 42-3.

12 Id. at 43.

13 Id. at 23.

14 IIT v. Vencap, Ltd., 519 F.2d 1001, 1017 (2d Cir. 1975)

15 Grant, Stuart and Diane Zilka, "The Role of Foreign Investors in Federal Securities Class Actions," Securities Litigation and Enforcement Institute 2004, Corporate Law and Practice, Course Handbook Series Number B- 1442, p. 6.

16 Id.

17 Id.

18 The majority of cases were either settled or dismissed before this phase, or remain pending.

19 American Bar Association, "Securities Class Actions in a Global Economy: Investor Claims Against Non-US Issuers," 2007, p. 10.

20 Id. at 13.

21 The majority of cases were either settled or dismissed before this phase, or remain pending.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.