Foreword

June 2009 As the world economy continues to grapple with the worst effects of global recessionary and downturn pressures and as stimulus packages and interventionist policies are announced in succession, a constant theme in political leaders' speeches in recent months has been talk of facilitating an infrastructure-led bounce to help restore some of the damage done to global markets. Major investments in new roads, bridges, energy plants and railway lines and the jobs these would create would unleash a positive economic stimulus that would usher the world economy back on the road to recovery – or, at least, this is the mantra.

The fork in this road, however, is that the recession/downturn has reduced tax revenues and put greater fiscal pressure on government budgets. Therefore, governments the world over are likely to become even more reliant on the private sector as an essential component in delivering infrastructure, and project finance is arguably the key vehicle to making this happen.

Will public private partnerships come to the aid of the global economy? Can projects be rapidly and efficiently delivered or will they be stuck in the financial and political bureaucratic bottlenecks that create a log jam and often stunted their implementation in the good times?

Last year in Outlook for infrastructure: 2008 and beyond we concluded that the market sentiment was one of 'cautious optimism'. The credit market was suffering from liquidity issues, the Northern Rock and Bear Stearns rescues had taken place, but people still expressed confidence in the fundamental investment strengths of the infrastructure asset class. Since then, of course, the world has undergone remarkable and systemic change: Lehman Brothers, bank bailouts, the remuneration issue, TARP and asset protection schemes, AIG, Babcock, fiscal stimuli, stock market slumps and partial recovery, global recession. And in the infrastructure space (as in most others) any activity dependent on leverage came to a halt post-Lehman in September 2008.

And now, in the summer of 2009? There have been recent stirrings – the M25 financing in the UK, the French senior debt guarantee scheme, deals being financed (at a price and on tough terms) – and, particularly in the greenfield infrastructure market, there are governmental stimuli. It is the purpose of Outlook for infrastructure: 2009 and beyond to analyse whether the hopes of governments for infrastructure delivery resulting from stimuli and other initiatives are coming to pass. This is an analysis of the current state of the global pipeline for project finance and the conclusions that may be drawn. We hope you will find in this report some informative and thought-provoking new data and analysis that can help shed light on these issues.

Introduction

On a chilly Virginia day in January 2009, US President-elect Barack Obama clearly laid out the vital role that he saw major infrastructure investment playing in the government's efforts to end the recession and deliver stable longterm economic growth. 'To build an economy that can lead this future, we will begin to rebuild America. We'll put people to work repairing crumbling roads, bridges and schools by eliminating the backlog of well-planned, worthy and needed infrastructure projects,' he said.1

His ambitions have been echoed by governments across the world as political leaders have identified new infrastructure projects, delivered rapidly and efficiently, as a means of getting the world economy moving again. The investment, in anything from new roads to wind farms and nuclear plants, will deliver a stimulus that has the potential to drag key countries out of recession. Most governments see the private sector as a critical part of that efficient delivery. As President Obama said: 'It is not just another public works programme. Instead of politicians doling out money behind a veil of secrecy, decisions about where we invest will be made transparently and informed by independent experts wherever possible.'

This report examines the challenge that both public and private sectors face in ensuring that ambitious plans translate swiftly into 'shovelready' schemes that will create jobs and economic wealth. Using data from Dealogic (as at 17 May 2009), the financial data and software company, our analysis examines the current state of the infrastructure project finance market.

The report analyses the data to show:

- the monetary value of all private sector infrastructure project finance deals that have been announced;

- the proportions of those projects that are at pre-approval stage (announced but at an early stage); in tender (the selection process of project participants has begun); and in finance (the final bidder has been selected and bank finance either is being negotiated or has been negotiated); and

- the breakdown of these projects at all three stages, both by region and country and by sector type.

The results paint a detailed picture of the state of the infrastructure project finance sector; in particular, highlighting areas in which the sheer number and size of deals in the pipeline may cause a log jam as new deals start to come on stream, unless governments take radical steps to improve the efficiency of the procurement process surrounding major investment projects. With an estimated $1 trillion of infrastructure projects announced by governments and expected to enter the market, the time for action is now.

PROJECT FINANCE: THE TWO-TRILLION DOLLAR QUESTION

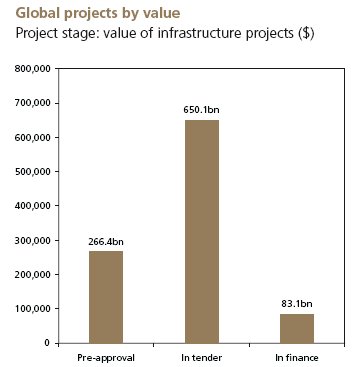

Almost a trillion dollars ($999.6bn) of project finance deals are in the global pipeline, according to the Dealogic data. Meanwhile the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates2 that the G20 group of developed and emerging economies will pump $1.48 trillion into the world economy in 2009 and 2010, of which two-thirds ($987bn) will come in the form of spending and the rest in the form of tax cuts. Although not all that spending will be on major projects, the headline figure of almost $2 trillion (G20 spending and project finance pipeline) represents 3.5 per cent of the world's entire economic output in 2009 ($55 trillion) as forecast by the IMF. If that was converted into projects on the ground this year, the global economy could expect a lot of bang for its bucks.

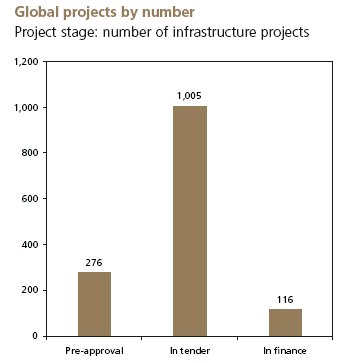

However, the data also highlights reasons for pessimism. Of the near‑1,400 projects working their way through the system, only a small fraction are close to delivering jobs and growth. We have broken project finance deals into three groups:

- in finance: meaning banks have been mandated and terms of financing agreed – which we have estimated at between six months and 2.5 years from work starting on the ground;

- in tender: project approved and selection of participants begun – estimated at between six months and five years from work starting; and

- pre-approval: project announced but at an early stage – estimated at between three years and 10 or more years from work starting.

Fewer than 10 per cent of the projects, by number and value, are close to delivery. The vast majority are still subject to detailed negotiations and a sizable minority are as much as a decade away from making an economic contribution. In terms of monetary value, more than a quarter are still at the pre‑approval stage.

Given the time lag, almost all of the deals currently in the pipeline predate the credit crunch and governments' initiatives to boost the world economy. Only those deals that are in finance may make an economic contribution this year and in 2010, when the recession is forecast to be at its worst. At best, only $83bn worth of projects are estimated to be within six months of delivery, equivalent to just 0.15 per cent of the world's total economic output; this is a sum unlikely to deliver an immediate kick-start to the economy.

The regional picture

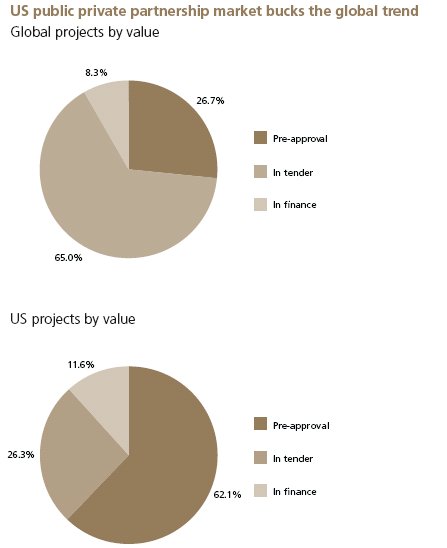

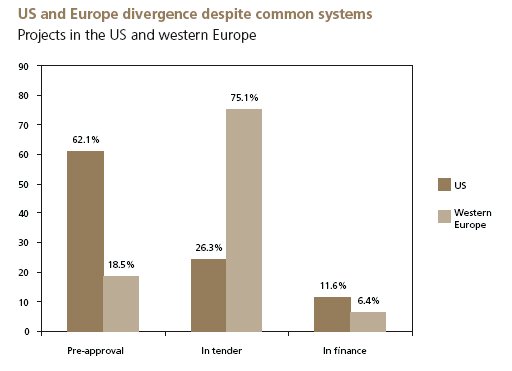

When it comes to a regional analysis, the data shows how some parts of the world are lagging behind the average performance. The most striking finding is that the US has by far the highest proportion of projects – 62.1 per cent, or $106.5bn – still stuck at the pre-approval stage, of which more than $71bn is made up of four railway projects. This is more than three and a half times the number of pre-approval projects, by value, in Europe. Only the Czech Republic in Europe and Sudan and Senegal in Africa have a larger log jam at that stage.

The US and western Europe are two economic blocs of similar size with equally advanced financial and legal systems. However, although western Europe has a clear 'bell curve' pattern in the flow of its deals, with small minorities either at early or very advanced stages and the bulk in the tendering process, a large majority of the projects in the US have not passed first base and moved into the tender stage. The quantity of deals still at the pre‑approval stage in western Europe (18.5 per cent) is very similar to that in the other major economic blocs, such as the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) on 21.3 per cent, Asia with 14 per cent, Australasia on 20.6 per cent and Latin America with 25.8 per cent.

The US's unique position is partly due to the fact that the use of project finance has emerged as a significant tool for delivering infrastructure projects only in recent years. Until recently, the US had a poor track record in the public private partnership (PPP or P3) arena in key areas such as transport. It was not until 2004 that infrastructure project finance really came of age in the US thanks to the $1.8bn lease of the Chicago Skyway toll bridge project in a PPP deal; this is a direct contrast with European countries, such as the UK, that have been using the PPP model since the late 1980s.

This is reflected in the data, which shows the size of project finance in the UK is 43 per cent of that in the US despite the fact the American economy is seven times larger than Britain's. The log jam in the US will become an extremely important issue as President Obama's American Recovery and Reinvestment Plan comes into force. With 65 per cent of the $787bn stimulus package devoted to spending3 on both large and small projects, new infrastructure projects will be joining the queue for private finance over the coming weeks and months.

Although the effects of the credit crunch and the recession have been global, the same cannot be said for project finance. In the Caribbean, just 0.1 per cent of finance is devoted to infrastructure projects, compared with 3 per cent in sub- Saharan Africa and 6.9 per cent in eastern Europe. Sub-Saharan Africa and eastern Europe have been particularly affected by the drying-up of credit and the slump in world trade. These areas are also particularly poor at getting the projects that are in negotiation to the final stages. Just 3 per cent of projects in eastern Europe and 5.3 per cent in sub-Saharan Africa are in finance, meaning that only a handful are likely to make an economic contribution during the worst of the recession. MENA has the largest share of projects in finance of any bloc, at 12 per cent by number and 15 per cent by value. A reason for this may be that the oil-rich states in the Gulf have the resources to carry out this work on a traditional procurement model, but choose to go down the project finance route for certain projects to gain the project management expertise that those deals bring.

The sectoral picture

The history of project finance is rooted in infrastructure – particularly in transport assets and energy projects. These sectors dominate the current sectoral spread across all major jurisdictions. Almost two-thirds of the $1 trillion in the pipeline ($659.2bn) are categorised as infrastructure, of which $186.2bn are for roads and $168.4bn for rail. Power generation projects account for 16 per cent and natural resources projects such as the production and distribution of oil and gas comprise 12 per cent.

It is likely that forthcoming projects will be weighted towards those areas. In a report we produced last year, Outlook for infrastructure: 2008 and beyond,4 we found that 61 of 100 Europe-based senior infrastructure industry executives expected energy utilities to be among the most active sectors, followed by renewable energy (56 per cent), roads (53 per cent) and rail (45 per cent) in the succeeding 12 months. The Obama administration's stimulus packages promise sweeping investments in energy, schools, housing and transport and the European Commission has outlined its €200bn ($278bn) European Economic Recovery Plan, which will bring forward capital projects into the current financial year.

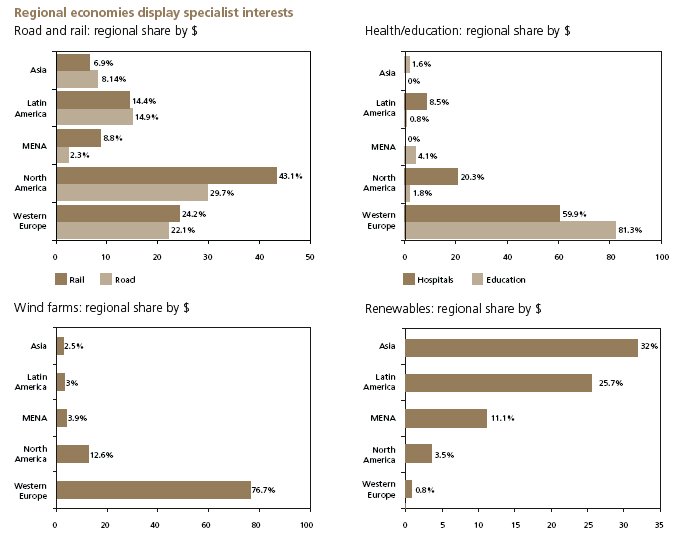

In trying to anticipate which countries will prove the most lucrative for the various sectors over coming years, it is useful to see how countries are currently weighted. Over one-third of US deals in the pipeline are for road-building (45 per cent) compared with just 13 per cent in Europe. This reflects the different cultural and political preferences in the two blocs. Due to the large distances between major American cities, a good road and rail network has been a longstanding priority. The US economy is more dependent on internal trade and less on exports than the European. This may explain why western Europe accounts for 28.5 per cent of the airport construction project deals (by value) – an area where the US does not have a presence.

Within natural resources, MENA and Latin America – which include most of the major oil-, gas- and mineral producing nations – account for almost half of all global investment projects under negotiation. Although MENA, which includes most of the OPEC countries, is weighted towards oil refinery projects, Latin America is focused on mining and gas field exploration, reflecting their respective strengths. Within core public services such as health and education, western Europe has the largest share of the market by a considerable margin, accounting for almost 70 per cent of the combined $54.5bn in those two sectors.

The data also shows some evidence that private sector project finance companies have been swift to pick up policy signals from governments about their future priorities. Although 'green' projects make up a tiny share of the global total, there is clear evidence that countries are developing specialist areas. In the case of wind farms, of 34 projects worth $13.0bn, western Europe has 18 projects with a value of $9.9bn, 53 per cent by number and 76 per cent by value, reflecting the high political priority put on alternative energy generation. Meanwhile, in Latin America, several governments have made renewable fuels a priority, reflected in their 25 per cent share of the $28.9bn industry.

Certain sectors that are likely to be the focus of government stimulus packages, as politicians attempt to foster sustainable long-term growth, are not yet major areas of interest for project finance. Other than one major $33bn project in Australasia, there are just a handful of telecommunication equipment projects worth less than $1bn. Water and sewerage projects, which will be a major area of growth amid mounting concern about the effects of global warming, currently attract just 1.6 per cent of finance.

Conclusion

Governments have placed great reliance on the role that infrastructure investment must play in delivering a short-term economic boost and providing the investment needed to sustain long-term growth. Yet the data shows that only a small fraction of the projects currently in the pipeline are likely to come to fruition during the recession, with the vast majority as far as a decade down the track. There is a heavy backlog of projects, which will only intensify as the next wave of projects comes on stream. It is therefore essential to identify the reasons for the backlog so the private and public sectors can take action now and implement reforms to ensure that the next wave of projects reaches the front line more quickly.

CLEARING THE LOG JAM

It is likely that governments across the political spectrum will look to PPP and private finance initiative (PFI) models to deliver investment. The severe economic downturn and the large quantities of public money needed to shore up the world's banking systems have left the leading economies with crippling fiscal deficits. Governments will turn to private capital to fill a massive funding gap for much‑needed infrastructure upgrades and improvements. The Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD) estimates $50 trillion is required for investment in roads, water, electricity, telecommunications and rail in OECD countries by 2030.5 In the US alone, the American Society of Civil Engineers6 says that $2.2 trillion is needed over the next five years to deal with its 'crumbling infrastructure'.

Industry executives across all major regions cite a wide range of obstacles to getting project finance deals through to financial close, which can be collectively summarised as financial, political and bureaucratic bottlenecks. They include a lack of sustained commitment to putting projects out to global private sector tender; inefficient procurement processes within government, such as a lack of strategic planning and low skill levels; and planning constraints. In the current economic climate, most market participants add financial log jams as a major obstacle to project finance, in the wake of the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Finance

The financial landscape has changed dramatically in the past 18 months. It is clear the credit crunch has put a tight squeeze on sources of finance for project finance. The monolinewrapped bond market, which, by value raised, was the main source of debt for PFI deals, is effectively closed to new transactions. This has put more pressure on the banking sector. Yet banks' capacity to provide new lending in the market is constrained as they seek to strengthen their balance sheets. As Andy Rose, an executive director of Partnerships UK, said in January 2009: 'The combination of capital adequacy requirements, reduced liquidity and higher funding costs has increased the strain on the project finance banking model.'7

Governments have already taken major steps to underpin banks and reduce real market interest rates. However, industry executives believe that a sizable proportion of the deals still at the in-tender stage are ones that have struggled to generate enough interest from banks. At the same time, these projects must compete for a reduced pool of finance with projects that were closed before the credit crunch and now need refinancing. The most high-profile victim of the crunch was the planned $2.52bn sale of Chicago Midway airport, which would have been the first US airport to be privatised. The deal collapsed after the winning consortium of private investors was unable to line up funding amid tight credit markets.8

Politics and bureaucracy

Infrastructure projects tend to have long lifespans, especially when they are based on a design, finance, build and operate (DFBO) contract, increasingly common in project finance. Yet governments often have much shorter durations, whether due to electoral cycles in democratic countries or because of regime change in authoritarian and developing countries. This creates a political risk for companies and investors looking to commit to a contract that may last for a number of decades. Long-term political commitment and sustained political support are needed if the private sector is to commit to a project.

The private sector has to take into account a number of political risks. At the most extreme level, these include appropriation of private sector assets. At the more mundane level, they include unexpected changes in laws and tax regulations. Even without unexpected changes, political bureaucracy can throw up barriers. Within federal countries, such as the US, decisions on individual projects are taken by the relevant city mayor or state governor even though the funding may come from central government. Political enthusiasm for project finance as a method of delivering major infrastructure projects varies greatly. In the US, for example, potential bidders have to deal with 50 state jurisdictions. Within those states, the attitudes of different city councils create further complexity for private concessionaires. This can be a very real risk, as a consortium led by Citigroup and Abertis found last year when its $12.8bn winning bid to privatise the Pennsylvania Turnpike under a 75-year lease was blocked by the state legislature.9 This helps to explain our finding that the US lags behind the rest of the world in terms of project finance.

A connected but equally harmful threat to efficient procurement is the temptation for governments at a central and local level to favour domestic suppliers over overseas competitors. The World Bank has collated evidence that protectionism has increased in 17 of the G20 nations since leaders pledged to eliminate it at their Washington summit in November 2008.10 At a local level, it may emerge on a parochial basis: 'Let's give the job to Hank down the road, like we always do.' However it manifests itself, protectionism means deals are less efficient and more costly than if they had been awarded on a fully competitive global tender basis. In the long term, governments that gain a reputation for protectionism will end up paying more for projects or simply find themselves shut out of the market.

Even when PPP deals gain political approval, they still face several bureaucratic obstacles. Moving an infrastructure project from the initial political decision to the final award of the contract to the winning bidder can take several years. There are many factors that can lead to unnecessary delays to the timetable. The need for planning approval is an important part of the democratic accountability of such projects. However, the system can be too cumbersome to help either industry or citizens,11 as shown by the eight years it took for Heathrow Airport's fifth terminal to move from initial application to final government approval. Industry executives in the US highlight the risk that a major project can become vulnerable to separate environmental approvals.

The wider procurement process can be fraught with delays. Executives in the US and Europe remark that the public sector often lacks skills in contract negotiation and project management. They also highlight an inconsistency of approach across different government departments, with officials applying different rules, approaches and practices to the procurement of essentially similar requirements.

CASE STUDIES: TALES FROM TWO REGIONS

The View from Europe

Non-executive Director of Partnerships UK and Financial Security

Assurance UK and former Chief Executive of John Laing

There is an urgent need for 'fresh thinking and creativity' by both private and public sectors in Europe to help unblock a log jam in private finance projects that could become a major issue as governments come under pressure to deliver successful new infrastructure projects, says Andy Friend.

As a former chief executive of the City of Melbourne in Australia and of John Laing, the construction company, he has experience of both sides of public procurement. Although the figures are a snapshot of the current market, his 'hunch' is that the share of European projects at the in-tender stage, currently 80 per cent of the total according to Dealogic, is growing: 'On the one hand governments are confronted with quite severe fiscal dilemmas and the deteriorating economy has made it harder to move projects through to implementation.

On the other, these new investment projects are competing for financing with the 2006 and 2007 vintage of projects and infrastructure acquisitions that are coming up for refinancing from the same depleted pool of finance. However, what we have seen so far in 2009 in the European market are heroic efforts by both private and public sector players to get the most major projects through to financing and implementation.' As evidence, he cites the £640m ($1.0bn) Greater Manchester waste deal and the £4.5bn ($7.2bn) 30‑year DBFO contract to widen the M25 motorway, both in the UK. He says the Manchester deal was sealed thanks to the involvement of HM Treasury's infrastructure finance unit and a £182m ($290m) loan from the European Investment Bank (EIB). The M25 project needed 16 commercial banks to come together to provide £925m ($1.5bn) of senior debt with a further £200m ($329m) loan coming from the EIB and a £215m ($354m) loan guaranteed by the commercial banks involved in the deal.

'So, in the short term, we are seeing significant global efforts to get projects across the line but the overriding medium-term issue is: how will governments be able to continue to draw on finance from private financial markets and deliver on a raft of public policies that require continuing and substantial capital investment?' he continues. 'There's a need for critical and fresh thinking and higher degrees of cooperation of an adult nature. Adult in the sense that the industry needs to look beyond the short term in a reflective and responsive way and draw on all the lessons of the past decade and a half in coming up with solutions appropriate for new times.'

Although the credit crunch and the surge in debt costs are cyclical factors, it would be foolish to assume that the post-crunch market will look the same as the pre-crunch one. There may have to be a radical shift from how projects were financed in the past. Fundamental issues will be up for debate: the distribution of risk between public and private sectors; decisions on which assets need to be in the public sector; how best to capitalise on pension funds' interest in infrastructure as a distinct asset class; and entirely new models such as building new assets with a settled intent of future sale rather than long-term ownership within the public sector.

Mr Friend notes that some of the backlog is due to longstanding issues such as the planning system and ineffective implementation of strategies by civil servants. 'Lack of commercial capacity in public agencies and being held hostage to overly bureaucratic decision-making have always been a nuisance. That remains as true in tough times as in more buoyant times.' He says that although it is important to tackle those issues, players in the market should not have an expectation that there will be a 'process of smooth normalisation' nor an expectation that when markets recover, the project finance landscape will look exactly the same as it did before. The industry itself is going to have to contribute to developing new solutions.

The View from America

Global Head of Infrastructure, Morgan Stanley

Sadek Wahba is surprised by the finding that 62 per cent of US project finance deals are still pre‑approval. 'I expected that figure to be even higher,' he says. 'We have deals in the US that will take years before they close. Or worse – years before they decide not to go ahead with them.'

Mr Wahba identifies two key reasons for the log jam in the system. The first is the fundamental demand for investment in everything from roads to waste treatment systems. 'There's enormous demand because of years of under-investment and neglect in certain areas and that means there is enormous demand for dollars to get into the infrastructure sector.' The second is a set of impediments that makes investing in infrastructure quite challenging. First, the involvement of private money to replace the current system of using tax-exempt bonds for infrastructure projects requires changes to legislation and political mindsets and the introduction of structures such as PPPs, which are less familiar to people. Second, the existing web of regulatory and environmental rules makes investment in infrastructure projects difficult. Third, the credit crunch, as Mr Wahba puts it, 'has not helped'. He is not sure how long it will last and, in the meantime, investors will not have access to the credit markets to raise money to fund these projects. Instead, deals have to be financed with 100 per cent equity, which is more challenging to put together.

However, Mr Wahba has a positive outlook for the sector. The Obama administration's stimulus package will not only stimulate the economy but also stimulate states, cities and agencies to 'think outside the box' as they realise that elements of the package come with requirements to involve the private sector. He says that a growing number of local governments – such as Chicago, Florida and California – now realise that budgetary constraints necessitate bringing in private finance and have changed legislation accordingly. 'There are log jams, but if you take a step back and ask if the willingness is there, the answer is "yes",' he says.

The energy and utility markets are a good example of a regulated and unregulated market working together, with the heavy involvement of the public markets through listed companies as well as private equity investors investing in pipelines, power generation, transmission and all basic infrastructure assets.

Ultimately it comes to a simple test, says Mr Wahba. 'Do you have more deals that are successful than are unsuccessful? The answer is "no".' One problem is that the concessions are often structured in a way that makes them 'uneconomic or unbankable'. 'You have privatisations and concessions in jurisdictions that require various approvals. It is incumbent on states to sell these to voters and that's a large undertaking.'

Mr Wahba believes that there is an urgent need for an 'open and frank debate' between all the players in the market about the pros and cons of the alternative ways of delivering infrastructure investment. This includes major political issues such as whether US states should still hold major assets on their books or seek to untie that capital and use the proceeds for spending on health and education. For example, the airport sector in Europe is entirely privatised but there is still no airport in the US in private hands. These are fundamentally different models. He believes that the project finance sector in the US will eventually match that of western Europe. 'However, I think it will take much longer than people think to get there,' he says.

CONCLUSION: BREAKING THE LOG JAM

This report exposes a major log jam in the project finance system. The vast majority of projects around the world are still out to tender or seeking finance, but in the US the majority are still languishing at the pre-approval stage. It is clearly in the interests of governments, infrastructure providers and investors alike to open up these bottlenecks as the stimulus packages being announced by politicians are implemented. The financial crisis adds further impetus for action. Although the credit crunch will make it harder to raise money, the fall in both economic growth and tax revenues will force governments to turn increasingly towards the private sector to deliver much-needed infrastructure projects. Just as the recession of the late 1980s and early 1990s provided the impetus for European governments, and the UK in particular, to opt for PFI to fill the funding gap for infrastructure projects, the current downturn should provide the motivation for the US authorities to use private finance in areas such as roads, rail, airports, ports and bridges that have historically been carried out within the public sector.

It is estimated that $3 trillion of US infrastructure in transportation, power, highways and streets are in public hands. In contrast, some 900 PPP projects in the UK worth $76bn have been signed off over the past 15 years, according to the OECD.12 However, the UK's venture into PPP encountered setbacks as civil servants and private companies got to grips with the concept. This led to inconsistency across government and made it impossible for departments to learn from each other, which led to many seeking to re-invent the wheel. Jurisdictions that are relatively new to the concept, such as the US and many emerging and developing economies, can learn from those experiences. All governments need to smooth out their procurement processes by designing standard forms of contracts with consistent terms and conditions and establishing familiar customs and practice when it comes to working with the private sector.

Many industry executives point out that although the credit crunch presents challenges, it also creates an opportunity for radical new thinking. Governments need to examine the current model of PPP projects, which tends to involve a long-term lease that passes 100 per cent ownership to the private consortium with eventual reversion of the assets to the public sector. Areas for debate include:

- changing the distribution of risk between the public and private sectors;

- reviewing the range of assets that are suitable for PPP or PFI;

- examining new models for PPP contracts that include permanent transfer of assets to the private sector; and

- governments joining winning consortia by taking long-term financial stakes in PPP projects.

Industry executives in the Middle East highlight the decision by Gulf rulers to offset the credit crunch's effects by either providing bridging finance, as in the case of Abu Dhabi and Shuweihat 2, or by extending the length of the concession, as Bahrain did for the Al-Dur independent water and power project, as examples of flexible thinking.

Countries embarking on simultaneous infrastructure spending programmes will face a competitive market in which governments must vie with each other to secure interest from potential investors and contractors to fund their projects. The countries seen as the most open and receptive to the delivery of PPP will be the winners. This issue will come to the fore in the delivery of large, technically complex projects such as the construction of new nuclear power stations, for which there are only a handful of companies capable of taking on the work.

An estimated $1 trillion of spending projects is set to enter the market. In the current economic climate, it is crucial that these projects bear fruit and do not simply join the existing log jam. To this end, it is vital that the public and private sectors work together and ensure that project finance efficiently delivers the investment that the global economy desperately needs.

Click here to see original document.

Footnotes

1 Speech by President-elect Barack Obama on 8 January 2009 at George Mason University, Virginia, USA: www.change.gov .

2 Update on fiscal stimulus and financial sector measures, International Monetary Fund, 26 April 2009: www.imf.org .

3 Assessing the G20 stimulus plans: a deeper look, E Prasad and I Sorkin, March 2009, Brookings Institution: www.brookings.edu .

4 Outlook for infrastructure: 2008 and beyond, July 2008: www.freshfields.com .

5 Infrastructure to 2030 (volume 2): mapping policy for electricity, water and transport, Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development, 2007: www.oecd.org .

6 Report card for America's infrastructure 2009, American Society of Civil Engineers: www.asce.org .

7 Speech by Andy Rose, executive director of PUK at PPP Financing Conference, 8 November 2008: www.partnershipsuk.org.uk .

8 'Chicago Midway airport privatisation deal cancelled', Wall Street Journal, 22 April 2009: www.wsj.com .

9 'Abertis, Citi pull offer for Pennsylvania turnpike', Bloomberg News, 20 September 2008: www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&sid=aNgirC5Rjxq4&refer=home .

10 Trade protection: incipient but worrisome trends, E Gamberoni and R Newfarmer, World Bank: www.worldbank.org .

11 'Terminal 5: the longest inquiry', J Vidal, The Guardian, 22 May 2007: www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2007/ may/22/communities.politics.

12 Infrastructure to 2030 (volume 2): mapping policy for electricity, water and transport, Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development, 2007: www.oecd.org .

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.