Abstract

With its rich history and evolving legal landscape, India has embarked on a crucial reformative journey through the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 ('IBC'). This legislative overhaul targets the intricate issues of personal insolvency, providing structured and efficient mechanisms to support individual debtors. This article delves into the transformative aspects of the IBC, highlighting its intent to streamline debt resolution processes and enhance economic stability. It examines the strategic objectives aimed at maximizing asset values, fostering entrepreneurship, and balancing stakeholder interests. While these reforms mark significant progress towards financial modernization, they also present challenges, including implementation hurdles and the need for broader awareness and engagement. This analysis not only sheds light on the operational impacts but also evaluates the broader implications for individuals navigating insolvency in India.

Personal Insolvency under IBC in India

The IBC, transformative legislation, represents a significant reform in India's financial landscape. While much attention has been focused on the corporate insolvency resolution process ('CIRP'), the IBC also encompasses provisions for personal insolvency, aiming to offer a structured and time-bound resolution for individual debtors. This article delves into the intricacies of personal insolvency under the IBC, elucidating its framework, processes, and implications.

Introduction to Insolvency in India

The landscape of personal insolvency in India reflects a stagnant regime marked by inefficiency and ineffectiveness. The research underscores the prevalence of delays within the Indian system, coupled with inadequate incentives for debtors and creditors to initiate proceedings. Accessibility remains a major hurdle, with prohibitive costs obstructing a significant portion of the population from seeking relief. Moreover, with its extensive court authority and intricate adjudication, the current legal framework necessitates a more streamlined approach. For instance, the imposition of a moratorium, crucial for suspending individual enforcement rights, hinges upon a court's formal declaration of insolvency.

The IBC, a comprehensive legislation, was enacted to consolidate and amend the laws relating to reorganization and insolvency resolution of corporate persons, partnership firms, and individuals in a time-bound manner. Its primary objectives, which are key to understanding its potential impact, are to maximize the value of assets, promote entrepreneurship, ensure the availability of credit, and balance the interests of all stakeholders. The IBC is implemented by the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India ('IBBI'), which oversees its enforcement.

Personal Insolvency under IBC

Personal insolvency is covered under part III of IBC, which includes individuals and partnership firms. The IBC classifies individuals into three categories for the purpose of insolvency and bankruptcy:

- Personal guarantors ('PGs') to corporate debtors ('CDs').

- Partnership firms and proprietorship firms.

- Other individuals.

Initially, the IBC focused on corporate insolvency. The insolvency resolution process for PGs was later introduced, following recommendations from the Report of the Reconstituted Working Group on Individual Insolvency ('RWG'). The RWG emphasized a phased implementation of Part III to accommodate the diverse market dynamics, stakeholders, transactions, and nature of proceedings.

Framework for Personal Insolvency

Personal insolvency under the IBC is delineated into two main parts:

- Fresh Start Process ('FSP')

- Insolvency Resolution Process ('IRP')

Fresh Start Process ('FSP')

The FSP provides a mechanism for the discharge of qualifying debts of an individual debtor. It is aimed at individuals with low income and assets, enabling them to start afresh without the burden of unmanageable debt. According to s. 80 of the IBC, a debtor who is unable to pay his debt and fulfils the conditions/eligibility criteria specified below shall be entitled to make an application for a fresh start for discharge of his qualifying debt under Chapter III.

Eligibility Criteria for FSP:

- Gross annual income should not exceed Rs. 60,000.

- Aggregate value of assets should not exceed Rs. 20,000.

- Aggregate value of qualifying debts should not exceed Rs. 35,000.

- The debtor should not own a dwelling unit.

- The debtor should not be an undischarged bankrupt.

- The debtor should not be an undischarged bankrupt.

- No fresh start process has been admitted for the debtor in the preceding twelve months.

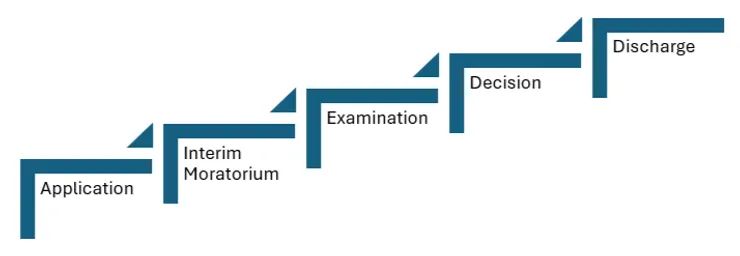

Process

- Application: The debtor files an application to the Debt Recovery Tribunal ('DRT') through a resolution professional.

- Interim Moratorium: On filing the application, an interim moratorium period begins, during which legal actions against the debtor for debts covered under the application are stayed.

- Examination: The resolution professional ('RP') examines the application and submits a report to the DRT.

- Decision: The DRT reviews the report and passes an order admitting or rejecting the application. If admitted, the moratorium continues, and the debtor is granted a discharge order for qualifying debts.

- Discharge: Upon successful completion, the debtor is discharged from qualifying debts.

Insolvency Resolution Process ('IRP')

The IRP is applicable to individuals and partnership firms whose debts exceed the threshold limit specified by the government (currently Rs. 1,000). This process is more structured and involves the appointment of a resolution professional to oversee the resolution.

Initiation

- The debtor or creditor can initiate the IRP by filing an application before the DRT under s. 94 and 95 of IBC.

- For PGs to CDs, the application is filed in the National Company Law Tribunal ('NCLT').

Process

- Application: Filed by the debtor or creditor, the application includes details of debts, assets, and financial affairs.

- Interim Moratorium: Similar to FSP, an interim moratorium starts upon filing.

- Appointment of RP: The DRT appoints a resolution professional who takes charge of the debtor's assets and affairs.

- Public Notice: The RP issues a public notice inviting claims from creditors.

- Submission of Claims: Creditors submit their claims, which the RP verifies.

- Preparation of Repayment Plan: In consultation with the RP, the debtor prepares a repayment plan.

- Creditors' Meeting: The RP convenes a creditors' meeting to discuss and vote on the repayment plan.

- Approval: If most creditors approve the repayment plan ('Plan'), it is submitted to the DRT for approval.

- Implementation: Upon DRT's approval, the Plan is implemented under the supervision of the RP.

- Discharge: Successful implementation leads to the discharge of the debtor from the remaining debts.

Role of RP

The RP plays a pivotal role in the FSP and IRP. The RP's responsibilities include:

- Assisting the debtor in preparing the application and repayment plan.

- Verifying creditors' claims.

- Supervising the implementation of the repayment plan.

- Ensuring compliance with the IBC provisions and protecting the interests of all stakeholders.

Impact on PGs

PGs to CDs hold a unique position under the IBC. Their insolvency process is intrinsically linked to the insolvency resolution process of the corporate debtor they have guaranteed. The NCLT has jurisdiction over cases involving PGs, ensuring a synchronized resolution process.

The IBC designates the NCLT as the adjudicating authority for corporate insolvency and DRT for personal and partnership firm insolvency. However, the IBC overlapped jurisdictions, especially for PGs.

S. 60 of the IBC clarifies that the NCLT has exclusive jurisdiction over PGs in the following scenarios:

- When insolvency and resolution processes for PGs are initiated.

- When the CIRP against the corporate debtor is pending.

- When CIRP is ongoing against the corporate debtor, any related applications against PGs are transferred to the NCLT.

- The NCLT assumes powers otherwise vested in the DRT for PG matters.

Legal Implications

- PGs can be pursued simultaneously along with the CD.

- The Plan for the CD may include provisions for dealing with the PG's liabilities.

- This linkage ensures comprehensive resolution and prevents guarantors from evading their obligations.

Legal and Judicial Landscape

The IBC has seen various judicial interpretations, particularly concerning PGs. In several rulings, the Hon'ble Supreme Court of India ('SC') has upheld the provisions of the IBC, emphasizing the holistic approach towards resolution and the non-exclusivity of PGs from the insolvency process of CDs. The SC in Lalit Kumar Jain v. Union of India1 resolved a significant issue regarding PGs of CDs and the IBC provisions that allow creditors to initiate insolvency proceedings against PGs. This ruling clarifies that individuals who provide personal guarantees for loans taken by corporate entities cannot escape liability when the corporate debtor defaults. Consequently, PGs, including promoters and directors, are now clearly within the scope of the IBC, ensuring that they are held accountable for the debts of the corporate entities they support.

Similarly, in State Bank of India v. V. Ramakrishnan and Ors.2 SC held that IBC does not allow PGs, such as company directors, to escape their independent and co-extensive liability to repay the entire outstanding debt. The SC upheld the validity of the 2019 notification, applying IBC provisions to PGs, ensuring their simultaneous liability along with CDs, also in the case of Committee of Creditors of Essar Steel India Limited v. Satish Gupta Kumar Gupta & Ors.3, the SC recognized the necessity for resolution applicants taking over a corporate debtor's business to start with a clean slate. The SC clarified that under IBC, the rights of subrogation and indemnification, typically granted to guarantors under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, can be extinguished if explicitly stated in the resolution plan. This ensures that new management can operate without legacy liabilities.

Challenges and Criticisms

While the IBC has streamlined the insolvency process, it is not without challenges, especially in the context of personal insolvency. In this context, the following challenges are likely to be faced by the litigants across the country:

- Awareness and Accessibility: There is a general lack of awareness about the personal insolvency provisions among individuals. Access to professional advice and resolution professionals is limited in rural areas.

- Implementation Hurdles: The procedural requirements and the involvement of multiple stakeholders often lead to delays and complexities.

- Judicial Capacity: The DRTs and NCLTs are burdened with a significant caseload, affecting the timely resolution of personal insolvency cases.

- Economic Impact: The economic impact of insolvency, especially on small businesses and PGs, can be severe, leading to financial instability and social repercussions.

Comparative Analysis

Comparatively, personal insolvency frameworks in other jurisdictions like the US (under Chapter 7 and Chapter 13 of the Bankruptcy Code) and the UK (under the Insolvency Act 1986) offer different approaches. These frameworks provide a mix of debt discharge and repayment plans tailored to individual circumstances. India's approach under the IBC seeks to balance creditor interests with providing a fresh start for debtors, though it is still evolving. The comparative analysis of UK and US personal insolvency laws reveals commonalities and divergences shaped by historical, economic, and legal contexts. The UK's recent focus on consumer debt and the US's emphasis on balancing consumer and business debtor needs offer valuable lessons for jurisdictions considering insolvency law reforms. Both systems aim to provide a fresh start for debtors while protecting creditor rights, demonstrating the complex interplay between debtor relief, creditor recovery, and broader economic objectives.

Future Prospects

The future of personal insolvency under the IBC looks promising, with potential reforms aimed at addressing current challenges:

- Streamlining Procedures: Simplifying the application and resolution process can enhance accessibility and efficiency.

- Awareness Campaigns: Increasing awareness through educational campaigns can empower more individuals to utilize the provisions effectively.

- Strengthening Infrastructure: Augmenting the capacity of DRTs and NCLTs can ensure timely and effective resolution.

- Digital Integration: Leveraging technology to manage filings, claims, and communication can reduce procedural delays and improve transparency.

Conclusion

Personal insolvency under the IBC represents a transformative step in India's financial landscape, providing a structured and equitable framework for individuals facing financial distress. While challenges remain, the evolving jurisprudence and potential reforms promise a robust system that balances the interests of debtors and creditors, fostering a culture of responsible borrowing and lending. As awareness grows and processes become more streamlined, the personal insolvency regime under the IBC is poised to offer significant relief to individuals and contribute to the overall financial stability of the economy.

Footnotes

1. (2021) 9 SCC 321: 2021 SCC OnLine SC 396.

2. (2018) 17 SCC (Civ) 458.

3. Civil Appeal No(s). 878/2019.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.