Meta Title: The article analyses reasons specifically focusing on the story of intimidation in Gujarat and the RTI Amendment Act of 2019 that has led to weakening of the Right to Information Act.

Meta Description: Citizens have become cognizant of rights pertaining to privacy, education, technology and most importantly "information". With the codification of the Right to Information (RTI) Act 2005, India pursued to uphold its basis of democracy, sovereignty by embracing accountability and transparency. But has the goal sustained? The article shall answer the same. This article analyses the causation that led to the weaking of the RTI Act by focusing on a story of intimidation in Gujarat, a state in India. The article also emphases on international aspect of RTI, supported by judicial pronouncements and certain suggestions for improved application of the legislation.

INTRODUCTION

The fight to know information or gain knowledge that concerns your private or public interest had been ongoing globally.1 This demand for greater accessibility to information has revolutionized the technological era we live in. After around 58 years of independence and various judicial pronouncements, the "Right to Information" was established as a statute2 that was enacted to protect, promote and defend the citizen's right to know while guarding their fundamental and human rights.

But with time, a tool that was enacted to protect the citizens interest has now itself turned into an imposed violative piece of legislation. There are many instances that prove the same, but in this article, we shall focus on how the appellate authority of Right to Information in Gujarat imposed a fine of ?10,000 on an applicant for merely using his right to information.

Keywords:

India, Gujarat, Right to Information, Imposition and Gujarat Information Commission.

A Story of Intimidation in Gujarat

In June 2021, a resident of Himmat Nagar, Gujarat filed an application under Section 63 of the RTI Act to the Public Information Officer (PIO) of the Sabarkantha District Court.4 The application requested the cause list of Fast Track and Special Courts during the first COVID-19 lockdown period (2020) instituted under the:

- Protection Of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012;

- Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989;

- Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005; and

- Bail-related cases.

The applicant yearned to understand the operational working of the subordinate judiciary and scrutinise as to priority cases (that affect the right to life and liberty of the particular applicant) were impartially listed and ruled off consequently.

It is important to note that information like that of Cause Lists are a vital part of ascertaining public accountability which actually is expected to be proactively disclosed under Section 45 of the RTI Act by the District Legal Services Authority's (DLSA) Public Information Officer (PIO) of Himmat Nagar. But the PIO did not disclose the asked information, creating substantial barriers in effective implementation and keeping up the spirit of the RTI Act. To add, the appellate authority obligated the applicant to attend the online court hearing supplementing their unfair bureaucratic expectation, which stems apathy towards the digitally divided conventional reality of India.

The whole proceeding was also an acute violation of the natural principle of justice, i.e., "audi alteram partem" as the applicating was unceasingly called out and harassed by repeatedly asking the reason for filing such an application which is downright against and violative of the provision alluded under Section 6 (2) of the RTI Act which avers that the applicant seeking the information shall not be required to present any reasons for doing so.

Further, the Appellate Authority also imposed a walloping fine of ? 10,000 on the applicant. Over and above, the public authority revealed information such as the name, address and contact details of the applicant to the local newspaper to oblige as a deterrent, which is not only a violation of the right to privacy but also constructs bigoted intimidation upon the RTI applicants from engaging in "procedural remedies" when denied public information under the RTI Act.

Is imposing fine on RTI applicants illegal?

In the said case, the Appellate Authority imposed a fine of ?10,000 on the appellant as a deterrence but it is imperative to note that there is no such provision in the RTI Act or the Gujarat High Court (Right to Information) Rules 20056, that authorises a public authority to impose fines or costs on an applicant. The process of filing an RTI application is not analogous to a usual court hearing. Furthermore, the appellate authority lacks the capacity to levy fines

JUDICIAL PRONOUNCEMENT

The landmark cases which have established the jurisprudence of the Right to Information are as follows:

- People's Union of Civil Liberties (PUCL) v. Union of India7 - The Supreme Court expanded the Right to Information as to know about the electoral candidates as the right of the voters.

- State of Uttar Pradesh v. Raj Narain8 - In this case the Supreme Court reiterated the precedence of the citizens over the government as they themselves elect the government and hence have the right to know about how the government functions, serves and implements the legislations.

- P. Gupta v. Union of India9 - The Supreme Court recognised the Right to Information as a sub-right of the Right to Freedom of Speech and Expression by further narrowing the ambit of protecting government documents from disclosure to the public.

Hence, the Apex Court has upheld the concept of how the Right to Know is bilateral to a democratically sound and open government and is implicit in the Fundamental Right guarantying freedom of speech and expression10, hence disclosure of information regarding the operational aspect of the government must be the general rule.

With respect to the Story of Intimidation in Gujarat where the RTI application was initially rejected by the Public Information Officer asserting that the information enquired (that is the Cause List) was not ruminated to be "an information on record or public information", it is pertinent to refer to Manish Khanna v. High Court of Delhi11, a Central Information Commission case, where the Joint Registrar and PIO held that records such as the Cause List which are however only temporarily maintained come within the purview of "Record" as per the Section 2 (f) of the RTI Act which defines "information" and hence would include information that is transitory as well which the applicant is allowed to access for any given period of time rationing that such information is in control of the public authority/officials.

Advanced by the insolence of the judiciary and denial of information sought in the legitimate public interest, the aggrieved appellant approached the Gujarat Information Commission (GIC) file a complaint under Section 18 (1) (f) of the RTI Act. The GIC then issued certain instructions to the Appellate Authority of Himmat Nagar but the authority did not reply to the said instructions within the stipulated time frame. In addition to the pending complaint with GIC, the appellate authority unfairly deducted the amount without any prior notice to the appellant.

How does this Story of Intimidation in Gujarat weakens the Act of RTI?

Even after precedents, strong jurisprudence, movement by the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) and formation of the National Campaign on People's Right to Information (NCPRI), illegalities and indicative intimidation still exists in the implementation of the RTI Act.

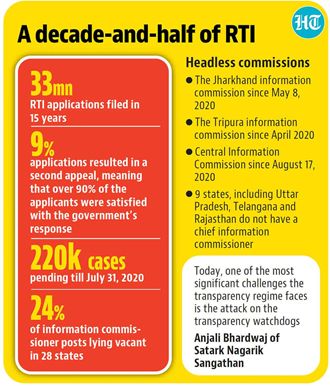

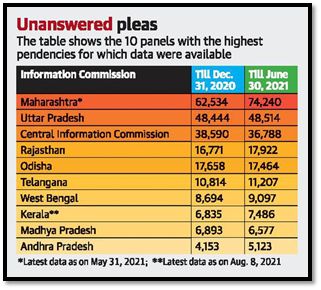

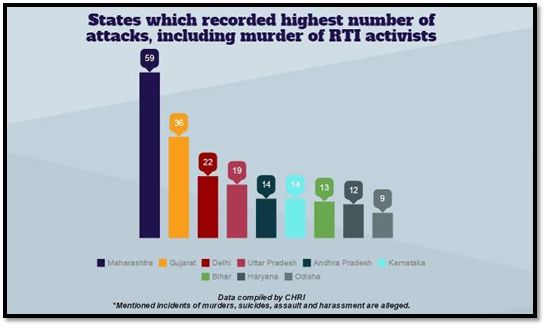

Nonetheless, the RTI Act has ensued to be powerless or deteriorated in its effective implementation for the following reasons:

- Narrow interpretation by the Public Information Officers and Subordinate Courts,

- Exorbitant delay in inducting for the subsequent vacancies, 12

- Irrational construal given by the Courts for classifying Information enquired as inconsistent with the provisions of the RTI Act,

- Arbitrary denial of information with consequent aggravation of the appellant,

- The Amendment Act of 2019 which certainly tampered the independent legislative spirit of the RTI Act.

Image 1: The Headless Commissions

Source: hindustantimes.com

- Backlog of numerous cases,13.

Image 2: Unanswered RTI Pleas

Source: www.thehindu.com

- Increasing instances of violence and harassment against the RTI activists.14

Image 3: Number of attacks including murder of RTI activists across major Indian States.

Source:

CHRI - Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative,

https://www.humanrightsinitiative.org/

Quantitative Analysis: A Research-Survey conducted by the Centre for Equity Studies in the year 2018-19 revealed that only 45% of the appellants received the information they had sought and out of the remaining 55%, less than 10% appellants trailed for a second appeal. Which signifies the abysmal state of the RTI Act, reasons for the same can be the following:

- Lack of penalization and strict actions against the blunders made by the Public Information Officers in responding to the RTI Applications.

- Around 90% of the appellants who did not receive information they had sought, do not take appropriate remedial actions against such deprivation.

Did the RTI Amendment Act of 2019 Kill the Autonomous Spirit of the Legislation?

The RTI Amendment Act of 2019 broadly amended the following Sections:

Section 13, Section 16 and Section 2715: The original Act prescribed the term of the Chief Information Commissioner and Information Commissioner as five years or until the age of 65 years (whichever is earlier), but after the amendment, the term was dissolved and the power to decide such term was vested in the hands of the Central Government. Similarly, the salaries and service conditions of the Chief Information Commissioner and Information Commissioner, also shall be prescribed by the Central Government, resulting in excessive entrustment and concentration of powers in the hands of the Central Government.

It is also significant to note that according to the "Pre-Legislative Consultation Policy", the pre-legislative scrutiny must take place before the final drafting and tabling of the Bill in the Parliament, for the public to raise objections, if any. But this did not happen before the tabling of the 2019 Amendment Act, signifying the unencumbered authority and arbitrarily actions of the Centre which may create trepidation of "government sanctions" in the minds of public officers.

CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS

To conclude, it is innocuous to say that the RTI Act has undeniably weakened in its implementation and application. To surmount this condition and improve the application of the statute, the following suggestions can be relied upon:

- Special Entrance Tests should be conducted to induct new applicants and fill in vacancies,

- The Appellate Authority should rely on reasonable and rational conditions to deny the imparting of information, for which a detailed list of classification can be drawn as and when cases are resolute.

- Strict Action should be taken against attacks that happen on RTI activists.

- A SpecialBoard or a Support Legislation should be set up that would penalize the Public Information Officers for their misconduct, corrupt prospection and transgression from what is stated in the RTI Law.

- India can also adopt the arrangement of having State RTI Legislations pertaining to the respective Subjects of the State List.

References

- Chetan Chauhan, Key posts vacant as RTI law completes 15 years, HINDUSTAN TIMES, Oct 13, 2020 05:33 AM IST, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/key-posts-vacant-as-rti-law-completes-15-years/story-RlFF1F88q2qRkmdP6Sg1fN.html

- Information Commissions grapple with vacancies, 2.55 lakh case backlog, THE HINDU, Oct 12, 2021 11:03 IST, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/information-commissions-grapple-with-vacancies-255-lakh-case-backlog/article36952124.ece

- Anusha R., A Story of Intimidation, Illegality and (No) Right to Information in Gujarat, LEAF LET, 7 February 2022, https://www.theleaflet.in/a-story-of-intimidation-illegality-and-no-right-to-information-in-gujarat/

- Aruna Roy and Meera M. Panicker Attacks on RTI Activists Are Rising. We Need Accountability Laws, THE WIRE, 2 Jan 2022, https://thewire.in/rights/attacks-on-rti-activists-are-rising-we-need-accountability-laws

- Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan - MKSS, Rajasthan, http://mkssindia.org

Cases:

- Manish Khanna v. High Court of Delhi, (2008) Appeal No. CIC/WB/A/2006/00839.

- People's Union of Civil Liberties (PUCL) v. Union of India, (2003) 2 S.C.R. 1136.

- State of Uttar Pradesh v. Raj Narain, (1975) 3 S.C.R. 333

- P. Gupta v. Union of India, (1982) 2 S.C.R. 365.

Legislations:

- The Right to Information (Amendment) Act, 2019, Act No. 24 OF 2019.

- Right to Information Act, 2005, Act No. 22 of 2005.

- Gujarat High Court (Right to Information) Rules 2005 in exercise of powers conferred under § 28(1) of the Right to Information Act, 2005, Act No. 22 of 2005.

- Indian Const. (1950)

Footnotes

1. Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan - MKSS, Rajasthan, http://mkssindia.org

2. The Right to Information (Amendment) Act, 2019, Act No. 24 OF 2019.

3. §6, The Right to Information (Amendment) Act, 2019, Act No. 24 of 2019.

4. Anusha R., A Story of Intimidation, Illegality and (No) Right to Information in Gujarat, Leaf Let, 7 February 2022, https://www.theleaflet.in/a-story-of-intimidation-illegality-and-no-right-to-information-in-gujarat/

5. § 4 of the Right to Information Act, 2005, Act No. 22 of 2005.

6. Gujarat High Court (Right to Information) Rules 2005 in exercise of powers conferred under § 28(1) of the Right to Information Act, 2005, Act No. 22 of 2005.

7. People's Union of Civil Liberties (PUCL) v. Union of India, (2003) 2 S.C.R. 1136.

8. State of Uttar Pradesh v. Raj Narain, (1975) 3 S.C.R. 333

9. S.P. Gupta v. Union of India, (1982) 2 S.C.R. 365

10. Art. 19 (1) (a), Indian Consti. 1950.

11. Manish Khanna v. High Court of Delhi, (2008) Appeal No. CIC/WB/A/2006/00839.

12. Chetan Chauhan, Key posts vacant as RTI law completes 15 years, HINDUSTAN TIMES, Oct 13, 2020 05:33 AM IST, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/key-posts-vacant-as-rti-law-completes-15-years/story-RlFF1F88q2qRkmdP6Sg1fN.html

13. Information Commissions grapple with vacancies, 2.55 lakh case backlog, THE HINDU, OCTOBER 12, 2021 11:03 IST, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/information-commissions-grapple-with-vacancies-255-lakh-case-backlog/article36952124.ece

14. Aruna Roy and Meera M. Panicker Attacks on RTI Activists Are Rising. We Need Accountability Laws, THE WIRE, 2 January 2022, https://thewire.in/rights/attacks-on-rti-activists-are-rising-we-need-accountability-laws

15. § 13, 16 & 27, The Right to Information (Amendment) Act, 2019, Act No. 24 of 2019.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.