- Switzerland follows suit with a one-year delay after the EU

- Swiss professional and official secrecy not affected

- Step-by-step guidance for practice

- We recommend to still enter into the EU SCC as a fallback

- One can continue to rely on the EU SCC(and many will)

More than a year after the European Commission, the Swiss Federal Council has now also adopted its adequacy decision for the "Data Privacy Framework" (DPF), thus facilitating the transfer of personal data to the USA in the area of data protection. On 14 August 2024, it decided to amend Annex 1 of the Data Protection Ordinance (DPO), which will enter into force on 15 September 2024. The amendment was overdue and is largely undisputed, at least in Switzerland.

In summary, the decision allows the transfer of personal data to US companies without further measures, provided that the companies are also certified for Switzerland under the DPF. If they are not, a data transfer agreement is still required with them, but in this case, too, the decision increases the legal certainty of the transfer. This is relevant because violating the relevant provisions of the Data Protection Act (DPA) can be criminally sanctioned.

The political background to the matter

We had already reported on the background in detail in a blog post on 17 October 2022. The reason for this was that the US President made further assurances regarding lawful access to data transferred to the USA by the US intelligence community as part of Executive Order (EO) 14086 in order to counter (in our view primarily politically motivated) criticism of the European Court of Justice (ECJ). In the "Schrems II" decision, this had led to transfers to the USA being considered problematic under data protection law, at least if there was reason to believe that such lawful access by the US intelligence community could occur.

It is disputed whether EO 14086 is sufficient to solve the problem identified by the ECJ and a "Schrems III" decision is expected in the next few years, where this question will need to be clarified. The European Commission's latest adequacy decision, which was issued in the summer of 2023 based on EO 14086 and has since allowed a more or less unhindered flow of data between the EEA and the USA, may then also be overturned. If this happens, we will again be in a shambles. It will probably be another political decision of the ECJ, and our expectation is that EU 14086 will be considered sufficient. Switzerland has followed suit for opportunistic reasons, both with Schrems II and with the current adequacy decision. Of course, this in no way diminishes its value.

Mutual adequacy decisions

The reason it took Switzerland more than a year to follow suit with its adequacy decision was, for once, not because of Switzerland, but because the adequacy decision first required an assessment by the USA regarding the adequacy of Swiss data protection and lawful access under Swiss law, as provided for in EO 14086. This was achieved on 7 June 2024 with a decision of the Attorney General, which cleared the way for the Federal Council to issue its own adequacy decision.

The Federal Office of Justice completed its own assessment of the adequacy of data protection in the USA under the "Data Privacy Framework" and in light of the means for lawful access by US authorities on 30 April 2024 and submitted it to the Federal Council. The assessment analyses both the requirements of the Data Privacy Framework and its enforcement, as well as the possibilities for US authorities to lawful access data that has been transmitted to the USA, and the safeguards provided by US law to that end. The assessment concludes "that the United States ensures an adequate level of protection for personal data that a controller or processor in Switzerland transfers to certified organisations in the United States under the Swiss-U.S. DPF."

End of the dispute over the CLOUD Act?

Although the Federal Office of Justice's conclusion is as brief and general as that of the European Commission in the considerations of its adequacy decision a year ago, the Federal Council's decision based on the assessment is in our view a clear statement that the US authorities' ability to access data – including the much-cited CLOUD Act – is compatible with the requirements of Swiss law. It thus clearly rejects the occasional but prominent claims made by data protection authorities that the CLOUD Act is contrary to the "ordre public" of Switzerland. Anexpert opinion published last year made statements in the main direction. This caused and still causes confusion in the public sector as to whether it is permitted to make use of providers with a connection in the US.

The Federal Council does clearly not share these concerns (which are presumably anyhow simply due to a misunderstanding of US law by some authors and data protection authorities in Switzerland), as it would otherwise never have rendered the latest adequacy decision, particularly in view of the preconditions set forth in Art. 8 para. 2 of the DPO that inter alia require compatibility of foreign lawful access laws with Swiss law. In the EU as well, there was never any serious doubt that the CLOUD Act is incompatible with European data protection; in fact, its provisions originate from the Council of Europe's Cybercrime Convention. Hopefully, this discussion is now off the table for the purposes of data protection in Switzerland (until it may again become an issue in case of "Schrems III").

Swiss professional and official secrecy: No change due to the DPF

However, the adequacy decision has not changed anything with regard to professional and official secrecy in Switzerland. Here, an exporter may still not have any reason to believe that, for example, the use of cloud services provided by a foreign hyperscaler will lead to lawful accessby foreign public authorities. This applies to any country, be it Germany, the Netherlands, Ireland – and of course also the US. This also has nothing to do with data protection. It is only relevant for data protection insofar as controller-processor-transfer is only permissible under Swiss data protection law if it does not violate any confidentiality obligations.

Professional and official secrecy holders will therefore always have to carry out an assessment of the probability of access by foreign authorities (Foreign Lawful Access Risk Assessment, FLARA) whenever they use a cloud service or other service with a foreign nexus, for which there is an established methodology in Switzerland. Exceptions are cases in which the disclosure of secret data abroad is permitted by law, contract or by a suitable waiver, even if there is an increased risk of foreign lawful access. However, there is nowadays a recognised set of measures that can be used to reasonably restrict such access by the authorities, especially in the cloud.

Only for certified companies

The Federal Council's press release on the adequacy decision for the Swiss-US DPF refers only to the transfer of personal data to the USA to "certified" US companies. Although this is correct from the Federal Council's point of view, it is far too narrow in practice. The adequacy decision can in fact also be used for mostothertransfers of personal data to the USA. This is relevant because most US companies either do not have certification or are unable to obtain it; certification is not available to certain industries. Intra-group data transfers to the USA also regularly cannot be based on certification for business reasons.

You can find out which companies are certified here. It is always necessary to check whether the certification also covers the "Swiss-U.S. Data Privacy Framework" and not just that of the EU, and for which data category the certification has been issued (HR data or non-HR data or both).

What is the "Data Privacy Framework"?

The Federal Council's decision in favour of the USA did not conclude that US data protection law as such is adequate; in fact, there is no data protection law in the US that applies nationwide, let alone one that we would consider adequate. In order to nevertheless make it easier for US companies to transfer data by means of an adequacy decision, the USA has created the DPF, which – like its two predecessors "Safe Harbor" and "Privacy Shield" – defines a series of data protection rules (analogous to European data protection law) to which US companies can subject themselves through a declaration and certification, whereby a distinction is made between personal data of employees and other personal data.

If these companies do not comply with these data protection rules, they can be sanctioned in the USA for violating their public data protection assurances, which does happen. Together with a number of other measures, participation in this program compensates for the lack of a general US data protection law. This is why the adequacy decision only applies to certified companies. The DPF exists in a version for the EEA (and the UK) as well as one for Switzerland.

Today, US providers and US online providers such as Microsoft, Google, Meta and Amazon in particular are certified under the DPF, as they want to simplify access to and use of their services and intra-group data traffic in this way because further measures would be required without an adequacy decision. In contrast, the DPF hardly plays a role in global data transfers taking place within global companies that have affiliates also in the USA. Certification would be too costly for them, as mentioned above.

The real challenge was not the DPF

This concept of a self-certification framework was never the real problem with data transfer to the USA; it has existed for years under different names. The problem was the aforementioned lawful access by the US intelligence community. This, however, affected all data transfers to the USA in the same way – including those based on the EU Standard Contractual Clauses (EU SCC). As this problem has been solved with EO 14086 and as it applies to all transfers from Switzerland from the US, i.e. including those that do not take place under the Swiss-US DPF, this also benefits transfers that rely solely on the EU SCC to ensure an adequate data protection by the recipient in the US. These transfers represent the majority of cases in which data is transferred to the USA.

For most US cloud providers that operate their business via EU subsidiaries (e.g. Microsoft, AWS, Google, OpenAI), the Swiss-US-DPF is not even necessary and does also not apply: Here, data is first transferred to the EU and only from there is transferred to the USA. These stop-over-transfers have already be covered by the European Commission's adequacy decision in summer 2023. The Federal Council's adequacy decision is only relevant for direct transfers to the USA, whereby under data protection law, it is not the physical transfer that counts, but where recipient is located: If a data centre is located in Ireland, but the party operating it and with whom a Swiss company has the service contract is located in the USA, then this legally represents a transfer of data to the USA, even if it stays in Ireland.

Relevance of the decision for the use of the EU SCC

But how can you benefit from the adequacy decision when using EU SCC? Unfortunately, this is also somewhat complicated. It is necessary to take a look at Art. 14 of the EU SCC, where the parties undertake to check whether there is reason to believe that there will be problematic access by authorities in the recipient's country before transferring personal data within the framework of the EU SCC. This check is known as a "Transfer Impact Assessment" (TIA) and is generally understood to be prescribed or expected by data protection law – including in Switzerland.

If data outside the Swiss-US DPF is transferred to the USA, those who rely on the EU SCC for doing so, must therefore check-out the lawful access rights of US authorities and determine whether they are problematic or not. They must basically do the same as the Federal Council has down in its adequacy decision. Thus, the person who intends to transfer data to the USA can basically piggyback upon the Federal Council's decision and declare that, after reading the underlying assessment, he or she agrees with the findings and conclude that the transfer of personal data to the USA is therefore unproblematic. If the Federal Council comes to this conclusion, it is unlikely that a private data exporter will be accused of not having carried out its checks correctly; in any case, we believe it would not be possible to criminally sanction them for not have complied with the data export rules of the DPA. In order to document this "pro forma" TIA, we have drafted a template (available here), as we have already done in a similar form for EU law (here).

How to proceed?

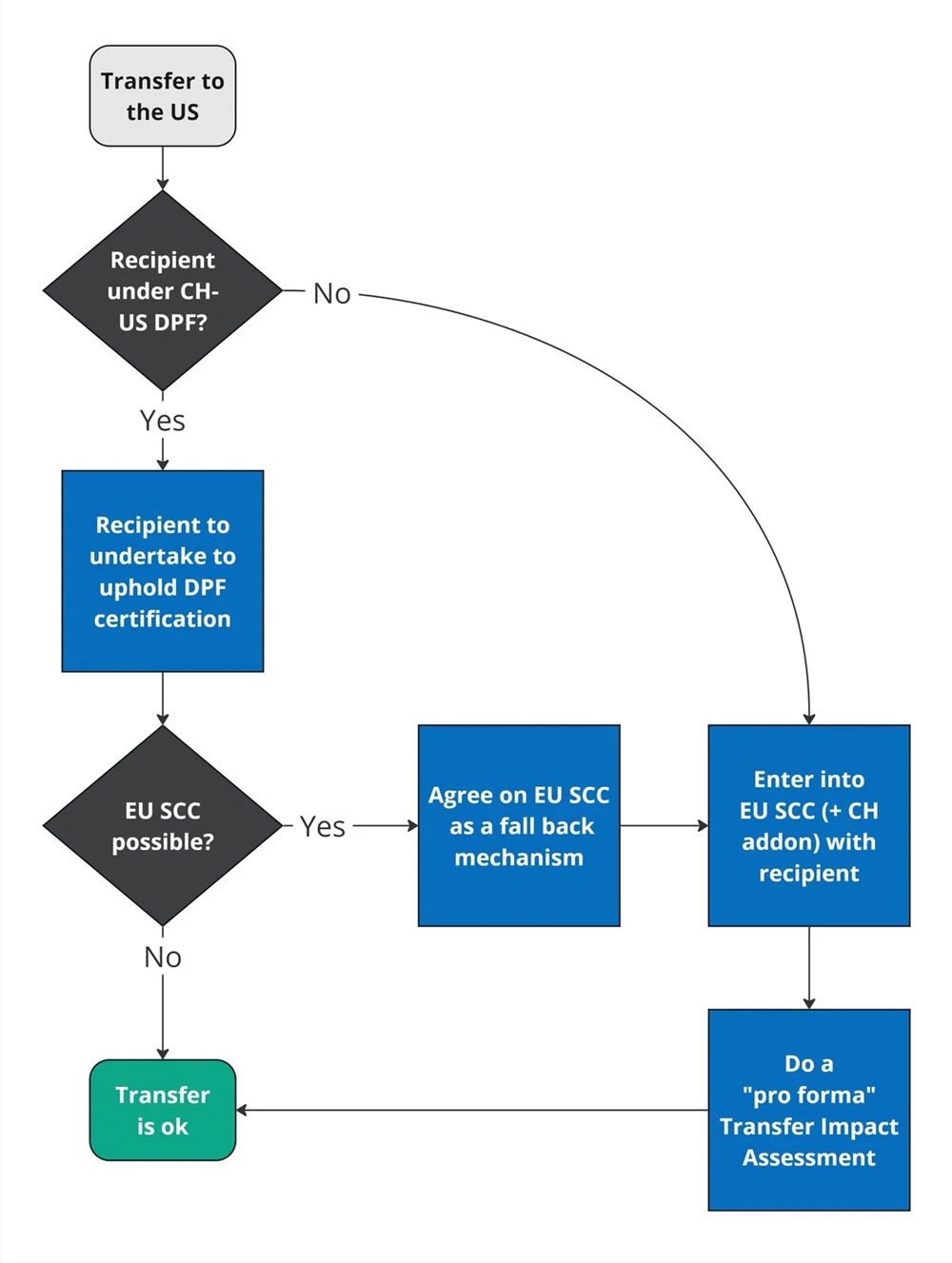

The following chart shows how to proceed in the event of a transfer to the USA as of 15 September 2024:

- Check the DPF program websiteto see whether the recipient is certified under the program. It is important to ensure that the certification also covers the relevant data categories. A distinction is made between data about employees ("HR data") and other data ("non-HR data"). Note: We have seen a report in Germany according to which there are allegedly different views on whether the certification for "HR data" only covers HR data of the importer (allegedly the US view) or (also) HR data of the exporter (the EU view). In our opinion, the certification of HR data also covers HR data of the exporter, and this in principle also seems to be the US position. So, probably a misunderstanding lead to the German report. In the FAQ on the DPF website, the US clearly states that the privacy policy can be used also for human resources (HR) data "transferred from the European Union and, as applicable, the United Kingdom (and Gibraltar), and/or Switzerland in the context of the employment relationship" (see Q7). It goes without saying that the privacy policy and certification must cover the data that the exporter wishes to rely on the DPF to transmit.

- If the recipient is certified, it is possible to proceed on this basis. From a purely legal point of view, no further steps are necessary; the disclosure of personal data to the recipient in the USA is permitted within the scope of Art. 16 para. 1 FADP without further contracts or the like. In practice, however, it is recommended that the exporter and importer agree in their contract that the importer must maintain the DPF certification or at least inform the exporter if this is no longer the case (and in this case be prepared to have the transfer of personal data to the USA governed differently or to accept that no more personal data can be transferred, with the corresponding consequences).

- If the recipient is not certified, the disclosure of personal data to them must be safeguarded in another way. In practice, this is usually done on the basis of the EU standard contractual clauses (EU SCC), which must be supplemented with an addendum for transfers from Switzerland (see our detailed FAQ, which has however not yet been updated to cover the adequacy decision). This is generally possible without any problems because the EU SCCs are accepted worldwide. However, no such regulation is necessary if one of the exceptions under Art. 17 DPA applies, e.g. if the fulfilment of a contract with or for the data subject requires the transfer. Previously, a transfer impact assessment (TIA) had to be carried out when using the EU SCC for transfers to the USA to document that there was no reason to believe that there would be problematic lawful access by US authorities. Strictly speaking, this is still legally required, as the transfer is outside the scope of the adequacy decision. However, in practice, the exporter can rely on the Federal Council's considerations and use this form to document pro forma for the sake of good order that a TIA was done. Once is enough.

- In practice, the question often arises as to whether both should be done, i.e. whether in the case of a DPF certified recipient the EU SCC should still be concluded. We recommend this where the opportunity arises. This is because there is some uncertainty as to whether and for how long the adequacy decision will be upheld. If it were to be overturned because the Federal Council repeals the decision following a corresponding ECJ ruling ("Schrems III"), there would at least be another basis on which the transfer of personal data could be reasonably continued; the transfer would possibly be accompanied by certain uncertainties, as was the case with "Schrems II", but it would not be clearly unauthorized. This is also standard practice: both means for transferring data to the USA are usually provided for in contracts. However, it is also clear that as long as the adequacy decision can be used, it will usually be given preference, i.e. the contract will stipulate that the transfer of data to the USA will take place only on the basis of certification under the DPF as long as this is possible. Legally, it is not necessary to choose between the DPF or the EU SCC. However, the EU SCCs provide for excessive obligations and cannot be amended. For example, they come with a clause that provides for unlimited liability and additional information obligations. For some companies (especially providers), it is therefore interesting to agree on the EU SCCs but suspend them until they are really needed for transferring data to the USA (and until that happens not to perform a TIA). This is achieved in the contract with appropriate wording that makes it clear that the transfer to the USA is based on the adequacy decision and certification under the DPF and not on the EU SCC. We therefore recommend that this point ("fall-back mechanism") be explicitly regulated in the contract and that the EU SCC not simply be agreed in parallel – unless the strict rules of the EU SCC are desired (which may well be the case on the customer side).

Those who have already agreed to the EU SCC basically do not need to do anything unless they do not like the EU SCC for the reasons mentioned above. In this case, it may be worth adapting the contract – possibly with the aforementioned fallback mechanism. Companies that rely on Binding Corporate Rules (BCR) do not have to do anything, either. There is also generally no need for action if one of the hyperscalers or another online provider is used and if the contract has been concluded with its subsidiary in the EEA, as is usually the case with Microsoft, AWS and Google, for example: In this case, the data legally speaking flows to the EEA first and the onward transfer from there to the USA takes place under EU law and is therefore already protected under the EU-US DPF, which has already been in force since summer 2023 (exceptions may exist where, as in the case of AWS for example, the provider has stipulated in its DPA that the Swiss customer must also agree the EU SCC directly with the US parent company).

We assume that the DPF will be used in dealings with providers but will not really be trusted as a long-term safeguard – experience with it has been too bad ("Schrems I", "Schrems II"). Yet, the issue of data protection compliance in the transfer of personal data to the USA should be off the table for the time being (as mentioned, with the exception of professional and official secrets) and that is a good development. Since the adequacy decision was issued in the EU the EU data protection supervisory authorities have been rather quiet on the topic of international data transfers, and this is good in our view, as there are more important issues in data protection.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.