Following Part 1 of our series on carbon markets, which discussed carbon capture, utilization and storage ("CCUS"), this second segment will examine the carbon pricing markets in Canada, Alberta, the European Union and the United States, compare and contrast such systems, and illustrate the challenges facing industry.

Energy transition and diversification efforts have dominated the political and industrial landscapes across the Western world. In Canada, much of the discussion has focused on the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change,1 the Paris Agreement2 and Canada's commitment to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.3 One critical component to achieving such objectives is carbon pricing.

As policy makers seek to control, reduce, and eliminate the production and atmospheric release of greenhouse gas emissions ("GHGs"), they have implemented policies which impose financial costs to producing and releasing carbon in the form of carbon dioxide ("CO2"), complemented by financial benefits to removing CO2 from industrial processes. Many of these policies encompass other GHGs, beyond CO2; however, for the purposes of this article, we will exclusively examine carbon markets in terms of CO2 and CO2 per tonne to describe these markets. For those producers who capture and sequester CO2 from their operations, a value is needed to assess those carbon molecules for monetization and trade. This evaluation is essential for developing the economics for CCUS projects. It is also necessary to those emitters who are unable to physically capture carbon from their operations and must rely on purchasing credits from other sources.

In this article, we will unpack what carbon pricing is, including various market and governmental approaches to carbon pricing, as well as the various market mechanisms which place a price on carbon. We will analyze and examine how different jurisdictions, such as Canada, Alberta, the European Union, and the United States, are currently approaching carbon market policy and putting a value on CO2 as a commodity. Furthermore, we will explore the details – and more importantly, the differences – of carbon pricing models across various jurisdictions in order to highlight the current challenges carbon markets and pricing pose to the industry. In other words, how do the various carbon pricing systems work and what challenges do they pose for the energy industry?

What is Carbon Pricing

Carbon pricing is the valuation placed on a unit of carbon either emitted into the atmosphere or removed from the atmosphere, usually in the form of a price per tonne of CO2. This valuation mechanism seeks to financially account for both the perceived harm caused by excessive CO2 emissions released into the atmosphere, as well as the perceived benefits of the removal of CO2 from the atmosphere. By placing a value on CO2 molecules per tonne, policy makers are seeking to reward and incentivize certain behaviours and at the same time penalize other behaviours, in a combination of proverbial carrots and sticks.

The underlying rationale for placing a price on carbon is to further climate change policies by creating and assessing a financial cost for producing and emitting CO2 into the atmosphere. See Part 1: Carbon Capture of this series for further discussion of climate change policy. Theoretically, the cost of the CO2 will align with associated external costs resulting from those emissions that the public otherwise pays for due to extreme weather events caused by climate change, such as: damage to crops due to drought caused by climate change; health care costs from heatwaves, droughts and flooding; and property damage arising from all manner of extreme weather events.

How Are Carbon Prices Established and by Whom?

Broadly speaking, there are two methods of establishing a price on CO2 emissions: compliance markets and voluntary markets. In a compliance market, the government establishes and implements a carbon price. In voluntary carbon markets ("VCMs"), businesses voluntarily purchase and sell carbon credits based on commercially negotiated terms, and the price of the carbon credit fluctuates according to a free market system. However, within these two broad markets there are a multitude of other markets and mechanisms which are discussed below. Understanding the markets and regulatory regimes behind such markets can be daunting, particularly as the various markets are not necessarily complementary. Understanding and navigating carbon markets is essential for industry from both a compliance perspective and a project economics perspective. The two types of markets may co-exist alongside one another but generally, unless stated otherwise, they operate separately.

Understanding Carbon Markets

The following summarizes some of the various forms of systems and mechanisms for establishing carbon pricing:

- An emissions trading system ("ETS") is a form of compliance system where a governing body sets emission targets through legislation and then regulates how emitters meet these targets. In an ETS, emitters can obtain, purchase and trade both emission allowance units that permit an emitter to produce one tonne of CO2 per unit ("emission units"), as well as government approved offset credits, such as those made available to encourage renewable energy development, CCUS and deforestation mitigation ("offset credits"). ETS systems are designed in such a way that entities which produce emissions have emission targets prescribed by law, which they can meet either by implementing internal abatement measures or acquiring emission units and offset credits in the open carbon market. An entity will develop an economic strategy to determine which method is more economical, depending on the relative costs of each option. Put another way, the government fixes predefined emission reduction targets, but emitters can strategically choose how to comply. The supply and demand of emission units create a market price on carbon within the ETS system.

- The two main types of ETS systems are cap-and-trade and

baseline-and-credit:

- Cap-and-trade systems are legislated systems which establish a cap or absolute limit on the total amount of emissions within the designated ETS jurisdiction, and which directly corresponds to a set amount of emission units to be shared by all emitters within the jurisdiction. Emitters must hold an emission unit for each tonne of CO2 that they emit in a given year. Consequently, emitters must utilize units that they have acquired and banked in previous years, or purchase units or offset credits on the market associated with the ETS, to ensure that they have an emission unit associated with each tonne of carbon. Note that some cap-and-trade systems limit the number of consecutive years over which emission units may be banked. As such, the price on carbon fluctuates in accordance with the market. An example is the cap-and-trade system in place in Québec.

- Baseline-and-credit systems are subject to baseline emissions levels which are set by a regulatory body for individual facilities. The government often creates legislation which designates specific facilities as part of the baseline-and-credit system, often in relation to their CO2 output. Under a baseline-and-credit system, emission units are issued to entities that have reduced their CO2 output below the designated level. Facilities which fall below the set level receive a "credit" (which, as used in this sentence, is not equivalent to an offset credit). These credits can be banked for future years or sold to other entities exceeding their baseline emission levels on an associated carbon market, which much like a cap-and-trade market, establishes a price on carbon in association with supply and demand on credits. Those emitters who do not exceed their baseline do not necessarily face penalties for doing so, but they also do not generate credits. An example is the system in place in Alberta, which has imposed a baseline-and-credit system for industry emitters who produce over 100,000 tonnes of CO2.

- A carbon tax, which is imposed by the government, often through legislation, directly sets a price on carbon by prescribing a tax rate per tonne of CO2 emissions. Most commonly, a carbon tax considers and corresponds to the carbon content of specific fossil fuels in relation to a price per tonne of emitted CO2 . A carbon tax differs from an ETS in that the price on carbon does not fluctuate. Note also that the emission reduction outcome of the carbon tax is not pre-defined. There is currently a carbon tax in place in British Columbia.

- A carbon offset credit market, in which companies elect to purchase credits associated with CO2 emission reductions from project or program-based activities. As such, it is the organizations which operate these projects and programs that issue offset credits. Some notable examples of carbon offset projects include reforestation, conservation of existing natural carbon sinks (such as grasslands, wetlands and forests), agricultural land management, seaweed sinking, technological optimization for emission reduction, renewable fuel switches, energy efficiency, CCUS and mineralization. These offset credits may be designed to integrate with a particular compliance market jurisdiction or part of a larger voluntary market where offset credits are sold both domestically in the country where they are generated or in other countries. As such, it should be understood that the purchase and sale of VCM carbon credits do not always occur in the same jurisdiction where the project itself occurs. Crediting mechanisms issue offset credits according to an internal accounting protocol and have their own registry. These credits can be used to meet compliance requirements under an international agreement, domestic policies or corporate citizenship objectives related to GHG mitigation.

As noted above, systems for establishing carbon pricing may be part of a compliance market, established by a government at either a federal or a provincial/state level, or may be entirely voluntary. What is critical to understand is that various mechanisms, such as a compliance cap-and-trade system and an offset credit VCM, may co-exist within the same jurisdiction, but it does not necessarily mean they will all be linked together. In fact, as will be discussed below, Canada is riddled with mini-carbon markets, many of which run parallel to each other without interconnecting.

The ability to make decisions concerning project development or assessing the value of capturing and trading carbon is directly impacted by the disjointed and varying markets. Furthermore, analysis of the markets in place in Canada, Alberta, the European Union, and the United States highlights that Canada's systems are is particularly patch-worked, which exacerbates tensions between policy goals of GHG reduction and industry reality of certainty of economics and risks and consistency of regulatory application and timing in order for the industry to flourish.

Jurisdictional Differences

Canada

Compliance Market

Canada has instituted a compliance market by way of the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act (the "GGPPA").4 The federal government has implemented a minimum national price on carbon pollution, otherwise known as a "floor" price on carbon, which increases over time. Presently, in 2024, the floor price is $80 per tonne of CO2 and will increase annually by $15 per tonne every year to 2030. The federal government enforces this floor price by way of two regulations: a regulatory charge on use of fossil fuel (the "fuel charge") and the Output Based Pricing System (the "OBPS"), which is an emissions charge on the output of carbon by industrial facilities.5 Both the fuel charge and the OBPS price carbon on a CO2 per tonne basis.

The fuel charge is sometimes colloquially referred to as a carbon tax, although the language used by the GGPPA and other official government documents describe it as a carbon levy. This is the portion of the backstop which directly affects Canadian consumers by way of payments at the fuel pump or in heating bills. The GGPPA designates which fuels the fuel charge will apply to, which are generally those which produce carbon emissions when combusted, vented or flared. The fuel charge is also notably controversial for the fact that the federal government has exempted home heating through the use of propone, which are generally used in the Maritime provinces, but no exemption exists for natural gas, which is more predominant in western provinces. The fuel charge rates reflect a carbon pollution price of $65 per tonne of CO2 in 2023 and which rise by $15 per tonne annually to reach $170 per tonne in 2030.

The OBPS applies solely to industry, specifically to industrial facilities which report production of carbon emissions that exceed 50,000 tonnes of CO2 per year. In Canada, current reporting requirements stipulate that all persons who operate a facility that emits more than 10,000 tonnes of CO2 in the calendar year must report emissions to Environment and Climate Change Canada. It is the responsibility of the facility operator to determine their emission output and report accordingly, and it is these reports which determine which facilities are covered by the OBPS.

The OBPS also incentivizes reporting in that facilities which are subject to the OBPS are able to purchase fuel which is not subject to the fuel charge. The facility will instead only be subject to carbon pricing on the portion of emissions that exceed that annual output-based emissions limit. Additionally, smaller facilities which do not meet the threshold but whose emissions are over 10,0000 tonnes of CO2 per year may apply to voluntarily opt in to the OBPS in order to purchase charge-free fuel.

Output-based standards are emissions-intensity standards for a type of activity or product (e.g., tonnes of CO2 per megawatt hour of electricity). The output-based standard is representative of best-in-class performance (top quartile or better), which in turn seeks to drive reduced emissions intensity. Facilities in the OBPS system that emit less than the limit receive "surplus credits" from the Government of Canada, which directly correspond to the surplus tonnes of CO2 not emitted. These surplus credits can be banked for future use or traded to another participant in the OBPS. Facilities whose emissions exceed their limit will need to either submit compliance units, such as surplus credits banked from a previous year or acquired from another facility, or offset credits, or pay the carbon price to make up the difference. As such, only the excess emissions, which are only a portion of a facility's emissions, are subject to a direct price obligation under this system. The excess emissions charge was $65 per tonne of CO2 in 2023 and will increase by $15 annually until 2030, resulting in an excess emissions charge of $170 per tonne of CO2 in 2030.

Accordingly, companies under the OBPS must take one or more of the following actions to obtain the necessary credits required for their operations: (i) use carbon allowances awarded to them by the government for the current year, (ii) use carbon allowances left over from previous years, (iii) purchase allowances from the EU carbon market, or (iv) trade with or purchase from other companies.

Together, the fuel charge and the OBPS form a "backstop"6 of minimum national stringency standards which, as a default, applies in all Canadian provinces and territories. As such, this backstop mandates that all Canadian provinces and territories will implement the floor price on carbon as prescribed by the fuel charge and the OBPS. If a Canadian province or territory crafts a carbon pricing mechanism that the federal government deems to be comparable in achieving the overall emissions reductions that the backstop purports to achieve, then that system will be put in place. Throughout Canada the various patchwork of systems put in place theoretically result in a uniform reduction of CO2 emissions across the provinces and territories, but the means of achieving such reductions vary.

Provincial and territorial governments may choose to either implement the federal backstop or devise their own system which aligns with CO2 emission reduction levels calculated in relation to the federal floor price on carbon. Put another way, it is possible for provincial and territorial governments to design a system which is friendly to their unique economic system in a way which is not built into the federal backstop. Additionally, the provinces and territories may choose to design one system that accounts for both parts of the backstop, as is the case with the carbon tax in British Columbia, or design one provincial system to account for implementing equivalent stringency standards as imposed by the fuel charge and another provincial system for implementing the stringency standards of the OBPS, as in Ontario.

Provincial and territorial governments with their own carbon pricing systems retain the proceeds directly and may use them as they see fit. In provinces where the federal fuel charge applies, the federal government collects the carbon levy initially but then is to return the majority of the proceeds directly to consumers through the Canada Carbon Rebate, formerly known as Climate Action Incentive Payments. The remaining proceeds from the federal fuel charge are returned to small and medium businesses, Indigenous governments and farmers. Provinces and territories that voluntarily adopted the OBPS can opt for a direct transfer for proceeds collected, whereas proceeds collected from OBPS backstop jurisdictions are returned through two OBPS Proceeds Fund program streams: the Decarbonization Incentive Program and the Future Electricity Fund.7

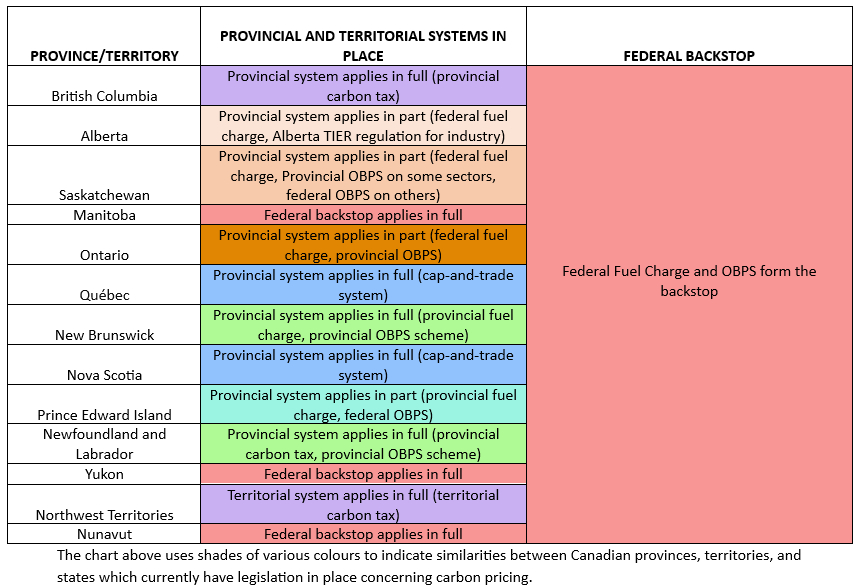

The federal system may apply in whole or in part in a jurisdiction depending on the system which is implemented by the provincial or territorial government. The backstop also supplements (or "tops up") systems that do not fully meet the benchmark. For example, the backstop could expand the sources covered by provincial carbon pollution pricing or it could increase the stringency of the provincial carbon price. As such, provinces and territories may put in place a variety of systems, such as the carbon tax in British Columbia or the cap-and-trade system in Québec. The chart below describes the current array of carbon pricing systems in place across Canada and illustrates the patchwork of systems and pricing mechanisms which industry and consumers must contend with.

Voluntary Market

It should be noted that in addition to a compliance market, there are also VCMs in Canada. There are currently VCM firms that engage in the sale and trade of voluntary carbon offset credits through the Toronto Stock exchange. These offset credits are freely traded at a free-market price and represent removal of tonnes of CO2 through projects such as planting trees, preserving rainforests or switching to more environmentally friendly cooking methods. However, it should be noted that under the GGPA, only offset units or credits which have been recognized under the OBPS regulations may be used to bring an emitter into compliance.

The federal government may not recognize a VCM because administratively the compliance system has yet to account for it. Additionally, there is the concern, both within Canada and other jurisdictions such as the United States, that the unregulated nature of VCMs means that the credits do not actually equate to the tonnes of carbon that they purport to stand for. There is concern as to the effectiveness of having an offset project take place in one jurisdiction and the sale of credits associated with that project in another.

The federal government stipulates that in order to be validated, the offset credit must have been generated from a project located in Canada with a project start date on or later than January 1, 2017, and have been verified by an accredited verification body in good standing, in accordance with the OBPS Regulations. As such, only provincial or territorial offset programs and offset protocols that meet the specific eligibility criteria outlined in the OBPS Regulations will be placed on the List of Recognized Offset Programs and Protocols for the federal OBPS.

Additionally, the federal government recently unveiled its own offset credit for purchase, which can be used for compliance by facilities operating under the federal OBPS system.8 The federal carbon credits are regulated under the Canadian Greenhouse Gas Offset Credit Regulations and require parties to register their offset project in accordance with the regulations in order to trade on this market. The regulations establish a quantification methodology for calculating the emission reductions or removals generated by offset projects, and includes other requirements such as those relating to project eligibility, monitoring, reporting and verification. As such, the federal credits provide another method for VCM credits to integrate into the compliance system, but only if that project can meet the requirements of the regulations.

Alberta

In Alberta, the federal fuel charge is currently in place alongside a provincial pricing system for industry which supplements the OBPS. The Technology Innovation and Emissions Reduction ("TIER") Regulation establishes an industrial carbon pricing and emissions trading system that automatically applies to "large emitters" – facilities that either emit at least 100,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent in a year or import more than 10,000 tonnes of hydrogen annually.9 In other words, TIER is a baseline-and-credit system as the limits are calculated on a facility performance basis. TIER provides that certain facilities which do not meet the large emitter threshold may opt into the provincial regulation as opposed to the federal GGPPA. Note that facilities which are designated under TIER are exempted from the federal fuel charge.

TIER imposes an annual emissions limit on these facilities by way of benchmarks. TIER allows for both facility specific and high-performance benchmarks. Through the facility specific benchmarks, a facility must reduce its emissions intensity relative to its own historical production-weighted average emissions intensity. High-performance benchmarks are based on the average emissions intensity of the most emissions-efficient facilities (performers in the top 10 per cent) producing each benchmarked product over reference years.

If a facility's total regulated emissions are below its annual emissions limit, it receives Alberta-based emission performance credits ("EPCs") which may be banked for future years or traded with other participating facilities. One EPC represents one CO2 tonne. If a facility exceeds its net emissions limit for a year, it must take one or more of the following actions to bring itself into compliance: (i) use accumulated EPCs, (ii) use emission offsets serialized on the Alberta Emissions Offset Registry, (iii) use sequestration credits, (iv) purchase EPCs from another facility that has excess credits, or (v) purchase fund credits from the Technology Innovation and Emissions Reduction Fund for every tonne it is over the prescribed limit. Under TIER, EPCs and emissions offsets combined may not be used to satisfy more than the designated amount of a facility's total compliance obligation for a single compliance year. TIER also includes a credit expiry timeline for emissions performance credits, sequestration credits and emission offsets.

Additionally, TIER encompasses a Compliance Cost Containment Program ("CCP"), which provides support to regulated facilities in emissions-intensive, trade-exposed sectors. Facilities with a first year of commercial operation prior to 2023, and for which total TIER compliance costs are greater than three per cent of facility sales, or ten per cent of facility profits, may be eligible for the following support mechanisms under the CCP:

- Additional compliance flexibility (exception to the credit use limit); and

- Additional free benchmark allocations.

TIER is designed to be tailored towards industries in Alberta in ways which the federal OBPS does not necessarily accommodate or allow for.

The European Union

The European Union Emissions Trading System ("EU ETS") is a compliance market spanning across 27 EU member states, as well as Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein, all of which makes it the largest carbon market in the world.10 The EU ETS also is linked with the Swiss ETS. Following Brexit, the United Kingdom has adopted the UK ETS, which is not presently tied to the EU ETS.

The EU ETS implements a cap-and-trade approach, whereby a limit is set on the total amount of GHGs that can be emitted in all of the EU by the installations and aircraft operators covered by the system. This cap is set by the European Commission, which is the governing body for all EU climate legislation and policies, and the cap decreases annually. Presently, the EU ETS is in what it describes as "phase 4", whereby the cap will decrease annually at an increased annual linear reduction factor of 2.2%. All countries in the EU ETS share one collective cap, which is reduced annually to correspond with the EU's GHG emissions reduction target.

The cap is expressed in "emission allowances", which are emission units that provide a company the right to emit one tonne of CO2. Every year, companies must obtain enough carbon allowances to cover their emissions in order to avoid a hefty fine. Accordingly, companies must take one or more of the following actions to obtain the necessary credits required for their operations: (i) use carbon allowances awarded to them by the EU ETS for the current year, (ii) use carbon allowances left over from previous years, (iii) purchase allowances from the EU carbon market, or (iv) trade with or purchase from other companies.

The United States

Federally, the United States is considered to be a voluntary market. Under this system both companies and individuals choose to offset their emissions through participation in VCMs. The creation and sale of carbon credits on VCMs can be achieved through various processes and offsets, such as renewable energy projects, electricity efficiency improvements, carbon and methane capture and sequestration, and land use and reforestation. Costs of offset credits can vary across VCMs, often depending on the perceived quality of the credit. Although there is no global scale for evaluating VCMs, the average value of VCMs is rising and is forecasted to continue to rise in conjunction with countries around the world pursuing GHG emission targets. The Boston Consulting Group stated in a January 2023 report that it estimates that VCMs will grow from a $21 billion USD value in 2021 to $40 billion USD in 2030.11 Morgan Stanley estimates in an April 2023 report that VCMs are expected to grow to about $100 billion USD in 2030 and around $250 billion USD by 2050.12

In May 2024, the Biden Administration released Voluntary Carbon Markets Joint Policy Statement and Principles.13 This document seeks to address critical commentary in relation to VCMs by providing seven key guidelines for "responsible participation" in VCMs:

- Carbon credits and the activities that generate them should meet credible atmospheric integrity standards and represent real decarbonization.

- Credit-generating activities should avoid environmental and social harm, and should, where applicable, support co-benefits and transparent and inclusive benefits-sharing.

- Corporate buyers that use credits ("credit users") should prioritize measurable emissions reductions within their own value chains.

- Credit users should publicly disclose the nature of purchased and retired credits.

- Public claims by credit users should accurately reflect the climate impact of retired credits and should only rely on credits that meet high integrity standards.

- Market participants should contribute to efforts that improve market integrity.

- Policymakers and market participants should facilitate efficient market participation and seek to lower transaction costs.

While the United States federal government has not implemented regulations, it should be noted that at the state level, eleven northeast states— Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont — along with California and Washington, currently regulate carbon pricing programs. The eleven northeast states make up the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative ("RGGI"), which is a cooperative, market-based effort to cap and reduce CO2 emissions from the power sector. California's cap-and-trade program (which trades with Québec) sets a statewide limit on sources responsible for 85 percent of California's GHG emissions.

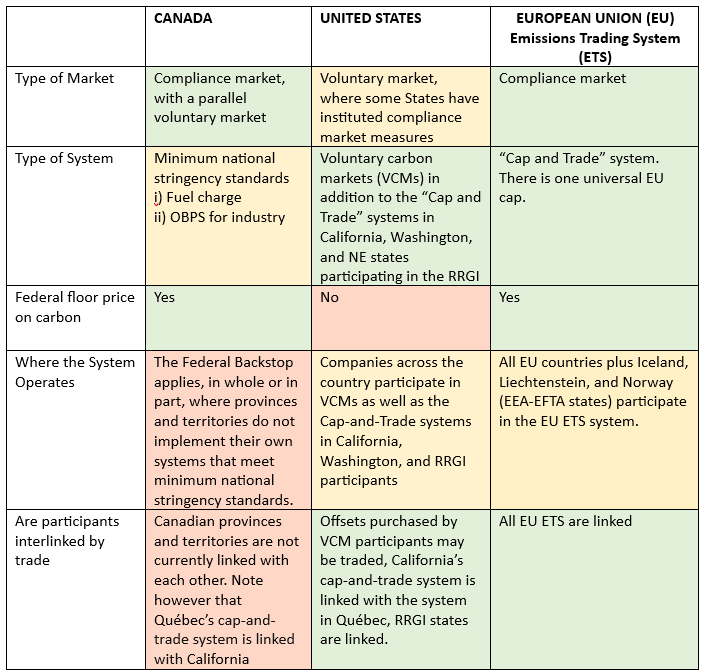

The table below compares and contrasts the approaches implemented by the Canadian federal government, the American federal government, and the European Union. Here, colour is used to represent the degree of similarities between Canada, the US, and the EU. Green represents a parallel between the three jurisdictions, yellow indicates some similarities with notable differences and red indicates that there are no similarities.

In the first row, Canada and the EU are both green because they are both compliance markets. The US is yellow as it is a voluntary market with some states having instituted a compliance market.

In the second row, the US and the EU are both green because they utilize compliance cap-and-trade systems. Canada is yellow because the minimum national stringency standards do not mandate use of a cap-and-trade system, but it does allow for it to exist in place of the federal backstop.

In the third row, Canada and the EU are both green whereas the US is red because it does not have a federal floor price on carbon.

In the fourth row, Canada is red compared to the US and the EU, as the federal backstop system in combination with provincial and territorial ability to devise their own system is unique to Canada.

In the fifth row, Canada is red compared to the US and the EU, as the various Canadian provincial and territorial carbon systems are not interlinked with one another.

Conclusion

The energy industry is global in scope with many participants being multi-national or international organizations with a global reach. Energy companies often look at their business and markets on a global scale based on their economic models. In the current patchwork of carbon markets and pricing methods with varying taxes and incentives, it can be challenging to determine how and where to apply capital to meet strategic growth plans. In Canada in particular, the jurisdictional differences between provinces and territories across the country pose challenges for the industry as compared to other jurisdictions, such as the United States. Ultimately, this makes Canada appear less attractive to industry participants who are considering projects on a global scale.

On the positive side, Canada does present unique opportunities due to its vast wealth of resources, geography, geology and abundance of available options for renewable energy, CCUS, and carbon capture.

Navigating the ever changing legal and political landscapes with various carbon policies, regulations, incentives, and penalties can be daunting; however, McMillan has the experience and expertise to assist.

Next on the Horizon: Cross-Border Carbon Transportation

In Part 3 of our series on carbon markets, we will delve into the intricacies of international carbon transportation. After capturing and compressing CO₂, transporting it safely and efficiently to storage sites is a critical step. This segment will examine:

- Logistical Challenges: Addressing the technical and infrastructural challenges of moving CO₂, including pipeline construction and maintenance.

- Global Market Dynamics: Understanding the need for a solid market price on a global scale to make carbon transportation economically feasible.

- Case Studies: Exploring successful carbon transportation projects, such as those in the North Sea and the US Gulf Coast, which serve as models for transporting CO₂ from areas without storage capacity to those with ample geological storage potential.

- Regulatory and Safety Considerations: Ensuring that transportation methods adhere to stringent safety and environmental standards to prevent leaks and other risks.

By linking carbon capture with effective transportation strategies, we can facilitate the large-scale deployment of CCUS technologies. This installment will highlight how these elements work together to form a comprehensive approach to managing carbon emissions.

Your Strategic Partner in Carbon Markets

McMillan LLP is dedicated to helping clients navigate the complexities of the evolving carbon market landscape. We provide expert legal guidance and strategic advice to ensure the successful navigation of both compliance and voluntary carbon markets.

Our legal teams are skilled at structuring and closing complex transactions in Canadian, US and international markets, and providing innovative transactional advice and solutions. Our understanding of business imperatives and our relationships with the regulators helps us deliver unmatched value to our clients.

Contact us to learn how we can support your understanding of jurisdictional complexities and nuances in order to capitalize on opportunities within the carbon market. Together, we can contribute to achieving a net-zero economy.

Footnotes

1 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 9 May 1992, 1771 UNTS 107 [UNFCCC .

2 Paris Agreement, being an Annex to the Report of the Conference of the parties on its twenty-first session, held in parties from 30 November to 13 December 2015–Addendum Part two: Action taken by the Conference of the parties at its twenty-first session, 12 December 2015, UN Doc FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1, 55 ILM 740 [Paris Agreement .

3 See Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act, SC 2021, c 22.

4 Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, SC 2018, c 12, s 186.

5 Government of Canada, " How carbon pricing works" (17 June, 2024).

6 See References re Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, 2021 SCC 11 (CanLII), [2021 1 SCR 175 at paras 20- 27.

7 Government of Canada, " Output-Based Pricing System Proceeds Fund" (5 May, 2024).

8 Government of Canada, " Canada's Greenhouse Gas Offset Credit System" (26 June, 2024).

9 Government of Alberta, " Technology Innovation and Emissions Reduction Regulation" (accessed 8 July, 2024).

10 European Commission, " EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS)" (accessed 8 July, 2024).

11 Boston Consulting Group, " Understanding the Voluntary Carbon Market" (19 January, 2023).

12 Morgan Stanley, " Carbon Offset Market Trends and Growth: 2050" (11 April, 2023).

13 US, the Biden-Harris Administration, Voluntary Carbon Markets Joint Policy Statement and Principles (Washington, DC: The President's Investing in America Agenda, 2024).

The foregoing provides only an overview and does not constitute legal advice. Readers are cautioned against making any decisions based on this material alone. Rather, specific legal advice should be obtained.

© McMillan LLP 2024