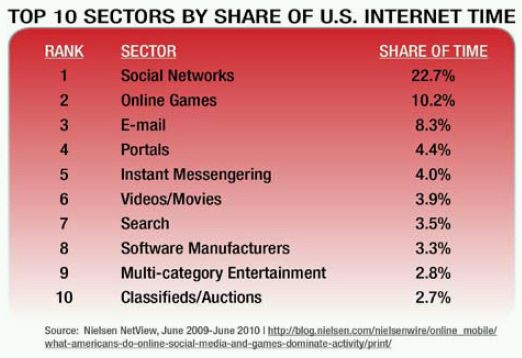

In this issue of Socially Aware, our guide to the law and business of social media, we take a look at a new lawsuit challenging Facebook's popular "Like" functionality, and we profile a recently-passed California law restricting the online impersonation of others. We also continue our analysis of the extent to which social media communications are protected from discovery under the Stored Communications Act. We summarize a defeat for YouTube in Germany regarding user-generated content. And, yes, as more and more companies integrate virtual reality technologies into the workplace, issues are arising regarding inappropriately-dressed employee "avatars" — in this issue, we provide our thoughts on this cutting-edge topic. Finally, we provide statistics on how Americans spend their time online (can you guess where social media usage ranked?).

Facebook Sued for Unauthorized Use of Minors' Names and Likenesses

Facebook is facing a class action lawsuit in California state court for the commercial use of children's names and likenesses without parental consent. The suit stems from Facebook's "Like" button – specifically, the allegedly unauthorized conversion of users' "Likes" of Facebookadvertised products and services into endorsements for such products and services – and is based in part on a California law that forbids the knowing use of a minor's "name, voice, signature, photograph, or likeness, in any manner, on or in products, merchandise, or goods, or for purposes of advertising or selling, or soliciting purchases of, products, merchandise, goods or services" without first obtaining consent from the minor's parent or guardian. The suit raises questions as to whether social media "Likes" constitute advertisements or endorsements.

The complaint alleges that Facebook first encourages the participation of children on its site, and then "markets the names and likenesses of those children for use by advertisers, representing to those advertisers that the use of the name and/ or likeness of the child as an endorsement of the advertiser's product can increase marketing returns by 400% compared to advertising that does not include an endorsement from the name or likeness of a child." Counsel for the plaintiffs has stated that Facebook "makes no effort to obtain parental consent" for these uses, contrary to the requirements of California law. Reactions to the lawsuit are mixed; according to MediaPost's Online Media Daily, some observers believe that the plaintiffs have a strong case, while others feel that "it doesn't necessarily make sense to treat 'likes' on Facebook as ads" and that the outcome of the suit is difficult to predict, particularly given that the applicable law went into effect well before the advent of social media.

YouTube Faces Damages and Injunction in Germany for Infringing User Uploads

In response to a complaint originally filed in October 2009, a state court in Hamburg, Germany recently ordered YouTube to pay damages to the owners of three Sarah Brightman videos that were uploaded to YouTube in violation of German copyright law, and enjoined YouTube from further distributing the copyrighted content. According to a statement by the Hamburg Regional Court, a company may be liable for hosting copyrighted videos without permission of the copyright owner. The court noted that YouTube was acting as a content provider — which requires the company to monitor the content hosted on its site — and merely requiring users to agree to a broad, standard statement that they had obtained all rights necessary to post the content was insufficient to relieve YouTube of its legal obligations. Further, the court stated that YouTube should request supporting evidence from each user that the user had obtained the necessary rights to post materials to the site, particularly given that users can use the service on an anonymous basis. According to ReadWriteWeb, a spokesperson for the court noted that "YouTube was treating content uploaded by its users as its own. That leads to a more strenuous duty to check out the content. The court came to the conclusion YouTube did not fulfill this [duty]." Google, YouTube's parent company, has announced that it will appeal the decision. For more information (in German), please visit this link http://justiz.hamburg.de/nofl/1403652/ container-presseerklaerungen.html .

In other copyright-related developments affecting YouTube's European business, YouTube, on September 30, 2010, entered into a deal with SACEM, a French society for songwriters and music publishers. As reported by The Wall Street Journal, YouTube will make payments to SACEM, which will then distribute the money to its members based on the number of times their songshave been viewed on YouTube. This agreement is similar to ones YouTube has entered into with trade organizations elsewhere in Europe, including the United Kingdom, Italy and Spain.

California Criminalizes Malicious Online Impersonation

California recently adopted a law criminalizing the malicious impersonation of another person online. The law, which will take effect on January 1, 2011, makes it a misdemeanor in California to impersonate someone online for "purposes of harming, intimidating, threatening, or defrauding another person." Violators face potential criminal penalties of up to one year in jail, fines of up to $1,000, and civil actions by victims.

The new California law targets cyberbullying and harassment in order to deter behavior such as that of the woman who was charged last year with posting a 17-year-old girl's photo, e-mail and mobile number on Craigslist's "Casual Encounters" adult forum following an online argument, and the so-called "MySpace Mom", whose alleged online bullying using the fake persona of a teenage boy allegedly led to a teenage girl's suicide. California State Senator Joe Simitian, who authored the new legislation, explains that California's existing law addressing impersonation issues, adopted in the 19th Century, "is outdated and was not drafted with 21st Century technologies in mind," while the new law "updates and strengthens California law by explicitly prohibiting" certain forms of online impersonation, or "e-personation." However, critics of the law – including the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the activist group The Yes Men (whose activities often center on impersonating members of powerful corporations) – claim that the law may have a chilling effect on free speech. The EFF notes that the bill "could undermine a new and important form of online activism," and that existing laws against fraud and defamation can be applied to online activities as well as offline activities (an idea echoed by other commentators).

Discovery of Communications Through Social Media Sites

Many social networking sites assert that the Stored Communications Act ("SCA") precludes them from having to comply with subpoenas requesting documents. Indeed, as discussed in the previous issue of Socially Aware, the District Court for the Central District of California, in its Crispin decision, has indicated that text and other content posted to social media "walls," if marked private, could be entitled to SCA protection.

Even if the SCA applies to private messaging and private postings on social media sites, however, this does not necessarily mean that any and all communications and content shared through social media sites is blocked entirely from discovery by litigants. A clever litigant may pursue alternate paths to obtain the desired information:

- First, if information is publicly available on a social networking site, it may be lawfully accessed under the SCA. Of course, accessing that information may still be subject to privacy, intellectual property, and other considerations and limitations under U.S. and foreign law, as well as restrictions included in the site's own "Terms of Use" (which, as we noted in our last issue, can be relatively complex and onerous).

- Second, even if information is not publicly available on a social networking site, the SCA does not preclude "lawful access" to such information. One approach might be to seek the information directly from the controlling party under Rule 34 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which could help force an unwilling party to provide "lawful consent" to the disclosure of electronic communications held by third parties. In fact, at least one court has ordered a plaintiff to redraft a third-party subpoena as a Rule 34 Request to the defendant. Further, in a recent decision, a New York court ordered a plaintiff in a personal injury case to grant defendants access to her current and historical Facebook and MySpace pages, even where the information was not publicly available. Relying on such sites' warnings emphasizing that information designated "private" may not remain so, the court held that there is no expectation of privacy, no matter what privacy settings were used.

- Third, even content that is marked "private" on social media services may be found in users' in-boxes. Because social media sites frequently send updates to end users through email (or even SMS) regarding other users' posts and messages, users' email accounts frequently contain copies of otherwise "private" social media messages.

- Finally, even if the information sought is not readily accessible, consider whether it can be construed as something other than an "electronic communication." One exception to the SCA is the disclosure of "customer records"—that is, "a record or other information pertaining to a subscriber to or customer of such service"—to any person other than a governmental entity. For example, a plaintiff may want to know when and how long an individual was using a particular social media site. The dates and times at which an individual accessed a social networking site are not "content" within the meaning of the SCA and are therefore not subject to the SCA's protections against disclosure.

The New Frontier of Employee Avatar Appearance Codes

Should companies reasonably ask employees to moderate the appearance of their virtual characters—or "avatars"—to conform to the company's dress code policies? Many companies currently maintain virtual worlds on their own computer networks (akin to the popular Second Life platform) that give employees the freedom to create their own virtual self-images that interact with the avatars of other employees. And given the almost limitless visual possibilities in creating and clothing avatars, they are frequently crafted to look far more risqué or outlandish than their real-world creators.

A number of commentators in the business world have already begun to weigh in on whether companies can or should lawfully regulate the appearance of their employees' avatars, when such appearance crosses the bounds of professional propriety and potentially offends colleagues. A well-publicized October 2009 report by IT technology consulting firm, Gartner Inc., found that "Avatars are creeping into business environments and will have far reaching implications for enterprises, from policy to dress code, behavior and computing platform requirements," and estimated that by year-end 2013, 70% of enterprises will have behavior guidelines and dress codes established for all employees who maintain avatars inside a virtual environment associated with the enterprise.

Although the first avatar appearance case remains to be seen, companies that are considering establishing employee avatar appearance codes should consider all of the following:

- Consider extending the existing employee code of conduct— including dress code policies—to include avatars in 3-D virtual environments. Like web-pages, blogs, and other social media, which are already frequently monitored and regulated by employers, avatars' appearance and conduct can have effects on real-world employees and situations. It may be appropriate to extend existing codes of conduct, including dress codes as well as policies against discrimination, harassment and retaliation, to virtual realms.

- Enforce avatar appearance codes equally and fairly. Employment discrimination laws require that employers establish uniform guidelines applicable to all employees. Any effort at regulating avatar appearance and behavior should apply equally to all employees.

- Avoid the pitfalls of content-based regulation. Employers should take care not to develop avatar appearance requirements that could form the basis of a discrimination claim. For instance, restrictions that may give rise to a claim of religious discrimination (i.e., bans on religious symbols) or age discrimination (i.e., requiring avatars to reflect a more youthful image than their real-life counterparts) should be avoided.

- Train employees on the risks and responsibilities of workplace avatars. Avatars provide an outlet for imagination, fantasy, and escape in the modern workplace. Employers should counsel employees who maintain avatars in the company's digital world that these opportunities come with an attendant responsibility to avoid behavior and appearances that might reflect negatively on the company.

Because of the generality of this update, the information provided herein may not be applicable in all situations and should not be acted upon without specific legal advice based on particular situations.

© Morrison & Foerster LLP. All rights reserved

We operate a free-to-view policy, asking only that you register in order to read all of our content. Please login or register to view the rest of this article.