Estate of Graffiti Artist Sues McDonald's Over Fast-Food Décor

The estate of Dashiell "Dash" Snow, better known as graffiti artist "Secret Snow"— has sued McDonald's over allegedly infringing use of Snow's street art in McDonald's dining rooms. The lawsuit in the Central District of California is the latest in a series of cases in which street artists are asserting their rights in copyright without any concession about whether the creation has other legal issues (i.e., trespassing or vandalism). Based on the survival of other recent similar cases, this latest case could be a headache for the giant restaurant chain, though it may have interesting fair use arguments based on the contrasting nature of the street vs. corporate uses.

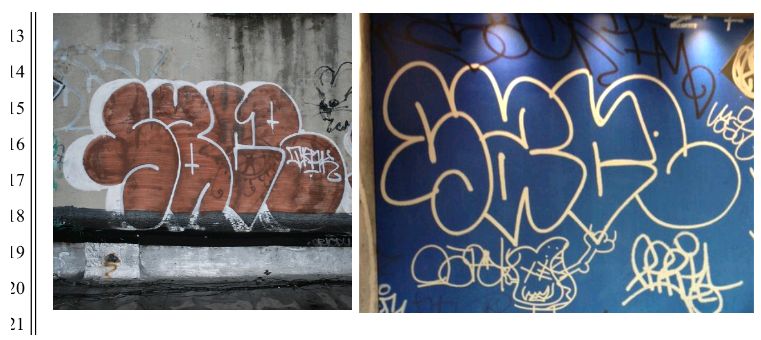

The Complaint very carefully sets Snow up as a contemporary artist, whose "street cred" was an essential part of his image. Needless to say, the appearance of his art in something as mainstream as McDonald's is at odds with that image, for which the Complaint says Dash would never have given permission. The Complaint includes this comparison of the original and the allegedly infringing use. It bears noting that while similar, the case for actual copying is not perhaps as clear as the Complaint suggests.

The Dash Complaint also picks up on the theory that survived dismissal in the Tierney v. Moschino case involving street artist "Rime"—namely, that identifiers in the images themselves violate the "copyright management information" (CMI) provisions of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. § 1202. This is somewhat different than the Tierney case, however, because in that matter the plaintiff alleged that deleting his signature interfered with CMI, while here Dash's estate argues that the presence of his signature creates an unwarranted association between him and McDonald's.

The case is a reminder of how quickly what was once examined has now become routine—the idea that street art, whether or not painted on property with permission—can be protected under copyright. The Tierney decision earlier this year (in the same court) drove the point home in analyzing the copyright issues at face value without questioning whether there was a copyright.

Many smart commenters have pointed to the "street cred" concept as a measure of the damages to a street artist. One wonders, however, if that idea might also give the defendants a stronger fair use argument. What is fair use in the visual arts is anyone's guess these days, but focusing in some order on the "transformative" nature of the secondary use and the impact on the market for the original work is where the battleground is, for sure. It remains untested in these street art cases whether the artists can prove that market harm if their work is publicly visible and not openly sold. The absence of a demonstrable market loss aids the defendant.

Similarly, while the Complaint very clearly alleges a risk of confusion between the street art and the corporate use, that is not the touchstone of either copyright or fair use analysis (though it is for the Lanham Act claim also asserted). If it was copied it is infringement, unless it is fair use. But could it be that in establishing so clearly the distance between Dash's original concept and the McDonald's use, the Complaint has unintentionally demonstrated how transformative the secondary use was? McDonald's for-profit motive will enter into the analysis, but it is not disqualifying.

Developments in this case will no doubt continue to drive these interesting discussions.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.