Hopes of an autumn resolution

World equity markets advanced and government bonds temporised in August as investors looked forward, in hope as well as expectation, to a more effective policy response on both sides of the Atlantic to the eurozone debt crisis.

World

Bond yields in Spain and Italy have fallen from the highs seen in mid-July due to speculation that the European Central Bank (ECB) is ready to step up its efforts and intervene once more in bond markets. Minutes of the recent Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting hinted at further quantitative easing (QE) in the US as the Federal Reserve keeps one eye on next year's looming 'fiscal cliff'. Yet there remains a fear that policymakers' actions, as we have seen so many times in the past, will not live up to market expectation. Time and again talk of central bank action has temporarily ignited markets, only to fall short on any kind of substance.

As we enter an important few months that may settle the fate of the eurozone, we remain cautious in the near term, given the risk that policymakers will again fail to deliver. While many equity markets look attractively valued on a relative basis, our long-term focus remains on good quality companies with robust business models, global franchises and high and sustainable dividend yields. We are also focusing on a suitably diversified mix of index-linked, conventional and good quality investment-grade corporate bonds. Our stance is designed to combine a measure of insurance against further deflationary pressures with reasonable exposure to the assets most likely to generate sustainable positive returns in a fragile economic environment.

UK

The upward revision to the second quarter GDP figure from -0.7% to -0.5%, does little to change the bleak outlook for the UK economy and failed to provoke a positive reaction from financial markets. The UK economy remains a big underperformer among the major developed economies. According to the official statistics, GDP is still more than 4% below its pre-crisis peak, although employment has shown a surprising degree of resilience. While Britain's Olympic athletes enjoyed an extremely successful games and restored some pride for the UK on the international stage, policymakers still appear to be short on ideas on how to stimulate the sluggish economy. The Bank of England, in its latest Inflation Report downgraded its growth forecasts from a somewhat optimistic 1.3%, to closer to zero by the end of the year, with growth of around 2% expected in 2013. The Coalition Government and the Bank of England are pinning a lot of hopes on the funding for lending scheme (FLS) that was launched on 13 July, designed to stimulate more bank lending. Further QE and/or another interest rate cut are likely to be delayed until the impact of the scheme becomes clearer. Although inflation picked up marginally in July, this looks to be the result of temporary factors. Consumer price inflation is expected to drop below the Bank of England's 2% target by the end of the year and provides further scope for a more dovish approach by the Bank's monetary policy committee.

Despite a backdrop of poor economic growth and an uncertain outlook for the eurozone, the UK equity market has remained surprisingly resilient. Seven of the ten major sectors have performed well year-to-date and the UK remains home to many good quality, 'nifty fifty' companies with robust business models and global franchises. However, given the continuing slowdown in China, the UK market's large weighting in mining companies will continue to be a drag on performance in the short term. A return to growth in many of the Far East's larger countries, should that materialise, would have a positive impact on the sector and the overall market.

US

US equity markets hit four-year highs during August but continue to listen with anticipation to the Federal Reserve for hints that a response to the mixed economic data and potential fallout from the eurozone is just around the corner. The continuing fall in consumer price inflation to 1.4% in July remains well below the Federal Reserve's 2% target and certainly provides scope for further stimulus. However, while market expectations of further monetary stimulus are clearly high, for the Federal Reserve to act so close to the presidential elections in November would be politically contentious. In addition to this, the real question remains whether the US needs further QE. There is little evidence to suggest that the previous two rounds of QE have had any lasting beneficial impact on the real economy. While equity markets have received a temporary boost, the impact has clearly been diminishing. With the S&P 500 and NASDAQ indices among the world's best performers this year, we expect the most certain ground for further monetary stimulus to come in response to a seismic shock from the eurozone, should this occur in the coming months.

Recent data releases continue to paint a mixed picture for the economy's progress. The two main Achilles heels since the last financial crisis, unemployment and the housing market, both now appear to have bottomed out, but look to be on different trajectories. The labour market continues to limp along with the unemployment level still a concern. Payroll and jobless figures remain range-bound. This reflects a lack of confidence in the corporate sector, with companies unwilling to commit to large, labour-intensive investment projects given the prevailing uncertainty. The outlook for the housing market, however, remains brighter and looks to be gaining significant traction. New home sales have increased around 36% since the trough in February 2011. With mortgage rates likely to remain low for the foreseeable future and a shrinking supply of housing, this could provide a genuine boost to the US economy and no longer act as a drag on confidence.

Europe

Despite a continued equity market rally and optimism among investors that the ECB stands ready to react, second quarter GDP figures continue to show a deteriorating economic environment throughout the region. Spanish and Italian equity markets have both rallied on the back of ECB president Mario Draghi's comments that the central bank will do "whatever it takes" to save the single currency. The future path of European equities remains closely linked to future decisions by the ECB and Europe's political leaders. A backdrop of deepening recession, rising unemployment and a lack of competitiveness across southern Europe is making it harder for policymakers to put together a credible plan for resolving the ongoing eurozone crisis. The divergence in performance between the troubled peripheral nations and stronger countries in the north, which is at the root of the eurozone's problems, continues to widen. While countries such as Germany and The Netherlands grew by 0.3% and 0.2% respectively in Q2, there were further contractions in Spain (-0.4%) and Italy (-0.7%). The eurozone as a whole looks set to fall further into recession by the end of the year.

Some of this deteriorating outlook appears to have been priced into markets already. With many eurozone leaders returning from their summer breaks, we are entering a potentially crucial period for the region with a Greek exit now very much back on the agenda if an agreement to revise the terms of its bailout package cannot be reached at the next planned summit in October. A crucial ruling by the German Constitutional Court on the legitimacy of the European stability mechanism, the proposed new bailout fund, is due on 12 September. While many investors harbour hopes that a credible and sustainable plan to save the eurozone can still be agreed by policymakers, the risk remains that without tangible signs of progress the markets themselves may force another outcome, with uncertain consequences for the region and the rest of the world.

Asia

Japan's vulnerability to slowing global demand and reliance on exports has further been highlighted by July's concerning trade data. Global equity markets reacted badly to news that Japanese exports decreased by 8.1% year-on-year last month. Exports to the troubled eurozone (which account for around 9% Japanese exports) have fallen by 25% in the past year as demand in the region continues to contract. More concerning still is that exports to China, Japan's main trading partner, have fallen by 12% over the year. The continued strength of the yen combined with slowing global demand has meant Japan's trade balance has slipped further into deficit. This presents a genuine long-term concern for a nation whose gross public debt currently stands at around 205% of GDP, historically financed by strong export-led growth and a substantial trade surplus. With domestic demand still weak and foreign appetite for Japanese equities still dictated by a strengthening yen, we are likely to see further pressure on the Bank of Japan to help reign-in the runaway currency and for the Government to pursue policies to help boost waning demand domestically.

The weak start to the second half of the year points to a continuing slowdown in China, the world's second largest economy. Policymakers are under increasing pressure to react to slowing domestic demand and sluggish global economic growth. Domestically, industrial production has dipped to 9.2% year-onyear, while retail sales have fallen to 13.1% in July, from 13.7% in June. As we have seen in Japan, weak global demand and a strong currency continue to impact Chinese exports which slowed significantly in July to a mere 1% from 11.3% in June. However, the silver lining for China is that, unlike many economies in the West, policymakers have both fiscal and monetary tools at their disposal. With inflation falling to 1.8% and now looking under control, there is further scope to stimulate the Chinese economy. While the eurozone continues to dominate the headlines, China's ability to achieve a 'soft landing' is also important in determining in which direction markets move next.

Market highlights

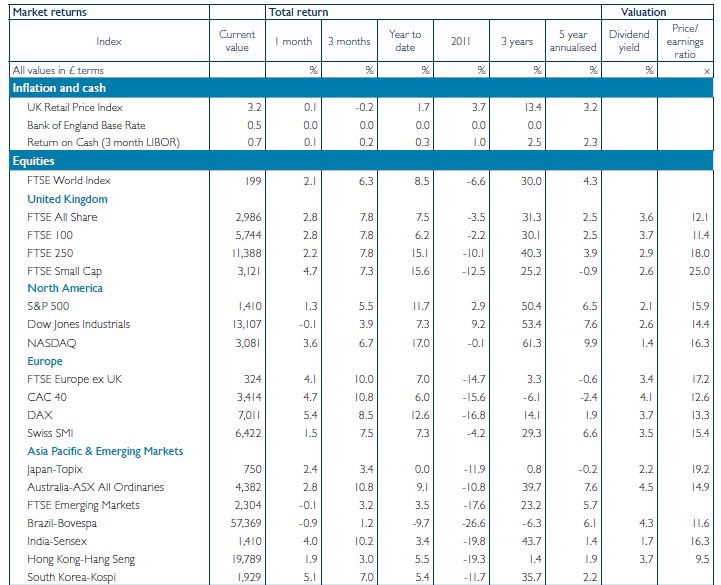

Market returns

The eurozone crisis

The future of the eurozone has dominated market sentiment for more than two years now. In this Q&A, Jonathan Davis explains the key issues. Jonathan was appointed as a part-time director and adviser to Smith & Williamson Investment Management in 2012. A former full-time business journalist at The Times, The Economist and The Independent, he is a director of two other investment companies, a regular columnist at the Financial Times and the author of three books on investment. You can read his blog at www.iidaily.wordpress.com

The eurozone crisis never seems to end. How close are we to a resolution?

It depends which crisis you mean. There is an immediate and serious crisis about the sustainability of the euro as a single currency for 17 of the EU's 27 member states. That is moving nearer to a resolution, with a number of key decisions needing to be made by the end of the year. But there is also a second crisis to do with the fundamental economic and financial problems many countries in Europe will continue to face whether or not the euro survives in its present form. That deeper-seated crisis is unfortunately still a long way from being resolved. It could take many years to fix.

What is the fundamental problem with the euro?

When the euro was launched as a single currency in 1999, with 11 members, it was intended to be just one step towards economic and monetary union across the EU. However, many of the other steps which are needed to make sure a single currency works effectively, such as integration of the banking system and a mechanism for agreeing and enforcing government budget limits, have still not been introduced more than a decade later. In that sense the euro project, though well-intentioned, was flawed from the beginning.

Does that mean it is bound to fail?

No. History does show that most currency unions eventually fail, typically when the economies in it start to move in different directions. This forces some members to subsidise or bailout others to ensure the currency's survival. The dollar is an example of one that has survived for more than 100 years, but the US has many characteristics, such as greater labour mobility and a clear national identity, that the EU lacks. The euro's misfortune is to have been by far the most ambitious project of its kind ever undertaken. The flaws in its design are unfortunately coming home to roost on a commensurate scale.

Is it all the fault of the way the euro was set up?

Not entirely. The flaws in design didn't matter so much when the world economy was growing steadily, as it did for most of the first nine years of the euro's existence. But the failure to establish an effective governance regime, or to stick to the government deficit limits laid down in the treaties that established the euro, have become critical since the global financial crisis of 2008. Trying to hold a single currency together in a debt crisis when economic growth is stagnating makes the task infinitely harder. It is compounded by the fact that for political reasons the creators of the euro deliberately set out to make the process irreversible, with no provision for any country to leave, however difficult their circumstances.

What triggered the current phase of the crisis?

It started in 2010 when it became clear that Greece, which had joined the euro in 2001, was unable to continue servicing the huge debts that it had run up in the years leading up to the banking crisis. In a single currency zone, the central bank can only set one interest rate for all member countries, regardless of whether that rate is appropriate or not for each country. Greece, along with Spain, Portugal and Ireland, was among the primary beneficiaries of cheaper money in the euro's early years. Its interest rates fell sharply after 2001, stimulating a huge private sector credit boom and a big increase in borrowing by the Greek Government. The build-up of eurozone debt was dangerous and unsustainable, but it got a lot worse when the global financial crisis hit, as most governments across Europe found themselves having to rescue their worst affected banks from bankruptcy, adding yet more to their public debt burdens.

Why is such a small country as Greece so important?

Greece was the first, but not the only, country to run out of money. With the help of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the other members of the eurozone organised a bailout loan, and then a second one, more grudgingly, in 2011. Bailouts have also been organised for two other struggling countries, Ireland (in 2010) and Portugal (in 2011). The problem is that if Greece is forced out of the single currency, it might not stop there. Once one country leaves, the risk is that others will soon follow as contagion spreads. More serious still is the risk that if Europe cannot convince the financial markets that it has sufficient firepower to defend even a small country like Greece, it will have no chance to save bigger and economically more important countries such as Spain. Nobody knows for sure how real these risks are.

Why haven't the rescue measures worked so far?

Europe's leaders have held more than 20 summit meetings in an effort to resolve the spreading crisis, but so far without managing to convince the financial markets that their plans are credible. They are hampered by genuine policy differences and the fact that without a central government, any substantive new steps have to be ratified by 17 individual member countries – a painfully slow business. Given the huge sums involved (more than €3trn to date in loans or guarantees), the bailouts are proving an increasingly difficult political sell. Public opinion has begun to turn against the euro in both the north of Europe, which has to foot most of the bill for the bailouts, and in the south, where the austerity measures are unpopular, making effective government responses harder To make things worse, this year Europe's economy has been slipping into recession, making the financial position of struggling countries, such as Greece, even worse, and the ability of richer countries, such as France and Italy, to fund rescues harder. More than half the countries in the eurozone have debt to GDP ratios well above the limits envisaged in the treaties that set up the euro. Spain, France and Italy are all struggling to bring their debts under control. Spain in particular is expected to have to seek a national bailout, given the scale of the problems in its banking sector, and its continuing inability to tap the markets for private sector funding at an affordable cost.

So what happens next?

At their most recent summit, Europe's leaders attempted to put more impetus behind the measures agreed at earlier summits. In addition to finalising the terms of a permanent bailout fund, the European stability mechanism, to help troubled members states in future, they also agreed to look at plans for moving towards a Europe-wide banking union, in an attempt to ring fence the problems of banks from those of governments. The ECB is also working on a plan to cap government bond yields. A series of official meetings in September will attempt to finalise the details. A team of officials from the EU, the ECB and the IMF (dubbed the 'troika') is meanwhile monitoring Greece's progress in meeting the conditions of its two bailouts, and another is monitoring Portugal. The Greek Government has again asked for more time to repay the loans advanced under its bailouts. The troika monitoring team is due to report by early October. A European summit later that month will have to decide, in effect, whether it can help Greece any further; and if not, how it plans to defend the rest of single currency zone against further enforced departures.

What will happen if Greece (or another country) is forced to leave?

Nobody knows for sure. It depends in part whether one country's exit leads to a much broader exodus. The short-term economic impact on the country leaving would undoubtedly be severe, most likely involving a deep recession, bank failures, bankruptcies and capital controls. While historical experience shows that countries that leave fixed exchange rate regimes do recover eventually, sometimes surprisingly quickly and strongly, it is inevitably a painful experience in the short term.

The knock-on effect on the remaining member countries is the bigger worry. Banks that have lent money to the departing country's banks and businesses would suffer losses. Thousands of business contracts denominated in euros would have to be written off or rewritten. In the worst case, a collapse in confidence could lead to bank failures right across Europe and a rerun of the financial crisis that followed the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008. But a worst case scenario is just that. Assessing the likely effects is difficult precisely because no provision was made in the treaties for how it could happen.

What are the odds on the eurozone breaking up?

The politicians cannot afford to countenance the possibility in public, but many analysts are convinced that it is only a matter of time before Greece is forced to leave the single currency. On the betting exchange, Intrade, the odds on at least one country leaving the euro before the new year are around 30% and before the end of 2013 more than 50%. There is no reason why that has to mark the end of the euro altogether. A smaller membership, built around the core European countries with the closest economic links, should in theory be easier to manage. The real issue is whether Europe's political leaders can muster sufficient political will and popular support to take the big steps, such as mutual guarantees of government debt, needed to ensure the single currency survives. There are also deep divisions between countries as to the best way forward. As the richest country in Europe, Germany in particular has been reluctant to shoulder the lion's share of the bill to bail out other countries without more certainty that bailout conditions will be met. Its own economy is slipping into recession.

What is the ECB's role in this process?

Compared to other central banks, the ECB has a relatively narrow mandate, confined to controlling inflation and maintaining financial stability across the eurozone. Its constitution specifically excludes it from buying the public debt of euro member states directly, a clause that was insisted on by Germany and others, essentially to prevent member states reneging on their tax and spending commitments. But many members of the eurozone want the ECB to be allowed to do more to help cap the interest rates on government bonds issued by Greece, Spain, Italy and others. The Federal Reserve and Bank of England have both been printing money to help their economies, something the ECB has so far only done on a relatively modest scale. Many analysts think that greater ECB involvement, combined with some degree of credible crossborder debt guarantees, will be necessary if the euro is to survive.

Is that going to happen?

It is possible, but not certain. The German central bank, the Bundesbank, remains strongly opposed to any such move by the ECB. Mario Draghi, president of the ECB, said recently that the bank will do "whatever it takes" to keep the euro intact. His officials are drawing up plans to help cap the rates at which troubled member countries can borrow in the public markets. Until the details have been fleshed out, it is impossible to know how effective these measures will be. Mr Draghi's statements have however served to remove some of the worries about the eurozone in professional investors' minds, at least for now.

How worried should investors be about the eurozone's problems?

It is clearly foolish not to have a contingency plan in case fragmentation takes place, given the likely disruption that would follow. The two outcomes – breakup or muddling through – could have very different consequences, making effective planning difficult. Most investors, however, are already well aware of the risks. They have long since sold their holdings of the most exposed European government bonds. European equities have also sold off, making them appear very cheap by historical standards. Policymakers and businesses have had plenty of time to prepare contingency plans for a possible Greek exit. But financial markets hate uncertainty and so investment performance is likely to remain subdued until the fate of the euro is clarified, and hopefully settled one way or another.

UK sector performance in 2012

One encouraging feature of the UK stock market's performance during August is that the gains were spread fairly evenly across all sectors of the market. This is in contrast to the market's performance since the start of the year, which has been notably uneven in sector terms. The weakness of companies in the energy and mining sectors have been a big drag on the UK market's performance, especially in the second quarter, a period which has been characterised by sharp falls in some key commodity prices, including oil, iron ore and copper, all of which are sensitive to changes in the pattern of global economic growth.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

We operate a free-to-view policy, asking only that you register in order to read all of our content. Please login or register to view the rest of this article.