- in South America

Cases from June

KEY CASE

- Albert Packaging Ltd and others v Nampak Cartons & Healthcare Ltd, Patents County Court – unregistered design right. The Patents County Court has held that the claimants had design right in the shape of their carton, but that it had not been infringed by the defendant.

PATENTS

High Court – mobile phone patent

Nokia Corporation v IPCom GmbH & Co KG, [2011] EWHC 1470 (Pat), Floyd J, 16 June 2011

The High Court has held a divisional patent of a parent mobile-phone patent to be valid.

This action was another stage in the litigation which is pending in a number of jurisdictions in relation to the mobile telephony patent portfolio which the defendant, IPCom, purchased from Robert Bosch GmbH.

The claimant, Nokia Corporation, sought revocation of IPCom's European Patent (UK) No. 1,841,268 on the grounds of obviousness, added matter and insufficiency. This patent was divided out of the parent patent, European Patent No. 1,186,189. Like the parent patent, 268 was concerned with managing the problem of contention on a random access radio channel uplink between mobile phones and a network base station ie how one controls access by mobiles to a random access radio channel or RACH between the mobile and the base station (the "uplink"). Where the uplink from a mobile station is a shared random access channel, there is a danger of collision between users' signals, allowing stronger signals through and preventing weaker ones. This competition is called "contention". It can be tackled in numerous ways. One set of ways in which the problem is tackled is by restricting access to the channel.

The parent patent was found to be invalid in an earlier action in which Floyd J refused (on procedural grounds) IPCom's attempts to introduce claim-narrowing amendments, one before and one after judgment. The claims of 268 resembled those which IPCom were trying to get into the parent action by amendment: but no procedural objection was taken on this ground.

In response to the action for revocation, IPCom made a conditional application to amend the 268 patent. In addition, by counterclaim, IPCom alleged infringement of 268 in respect of a number of mobile phones sold by Nokia. Nokia denied infringement.

Nokia also sought declarations of non-infringement in relation to a series of further mobile phones. IPCom advanced no positive case in relation to these phones, but sought a declaration that the relevant Nokia phones were not compliant with the relevant mobile telecommunications standard (UMTS). Nokia applied for summary judgment in its declaratory action. That application was adjourned to the trial.

The court rejected all the attacks on the 268 patent based on obviousness. It held that the patent as amended was not invalid for added subject matter or insufficiency.

The court held there to be infringement by certain Nokia devices and granted a declaration of non-infringement in respect of other devices. IPCom's request for a declaration was refused.

IPO – entitlement provisions in Patents Act and CPC

Rigcool Ltd v Optima Solutions UK Ltd, O/182/11, 1 June 2011

A hearing officer has allowed an extension of time for an application for entitlement proceedings that was filed out of time on the second anniversary of grant.

Previously, an application to the IPO to commence entitlement proceedings which was filed on the second anniversary of the grant of the patent concerned, was held to be out of time (see May 2011 Bulletin).

The applicant requested an exercise of discretion under rule 107 of the Patents Rules 2007 to extend the period.

Rule 107 provides that an irregularity may be corrected if:

"(3)(a) the irregularity or prospective irregularity is attributable, wholly or in part, to a default, omission or other error by the comptroller, an examiner or the Patent Office; and

(b) it appears to the comptroller that the irregularity should be rectified."

The hearing officer allowed an extension of time of one day, so that the proceedings could continue.

The hearing officer said that references in the IPO manuals to "more than two years after the mention of grant" were unclear; in an earlier case in which the issue arose, the hearing officer had said that this was a difficult issue; and there was evidence that the IPO had accepted applications filed on the second anniversary.

IPO – Peer to Patent

http://www.ipo.gov.uk/about/press/press-release/press-release-2011/press-release- 20110601.htm

A pilot of Peer to Patent, a new tool designed to help improve the patent application process, was launched today. Peer To Patent is a review website which allows experts from the scientific and technology community to view and comment on patent applications.

It follows successful Peer To Patent websites that have already been run in the USA and Australia.

During the six month pilot, up to 200 applications in the computing field will gradually be uploaded for review on the website. These will include a range of inventions from computer mice to complex processor operations.

The first group of applications have been uploaded and are open for review by registered users for three months. Following this, the system will create a summary of the comments which will be sent to an IPO Patent Examiner, who will then consider these as part of the patent review process.

The UK pilot went live on 1 June 2011 and will end on 31 December 2011.

Patents County Court (Financial Limits) Order 2011 (SI 2011/1402), 8 June 2011

http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2011/1402/pdfs/uksi_20111402_en.pdfThis Order came into force on 8 June 20110. It affects all proceedings within the special jurisdiction of a patents county court in which a claim is made for damages or an account of profits. It states that the amount or value of that claim shall not exceed £500,000. In determining the amount or value of a claim, a claim for interest, other than interest payable under an agreement, or costs shall be disregarded.

There are appropriate transitional provisions.

IPO – consultation on patent infringement in pharmaceutical trials

http://www.ipo.gov.uk/consult-2011-bolar.pdf

The IPO has launched an informal consultation on patent infringement in pharmaceutical trials.

The purpose of this consultation is to investigate the impact, if any, of UK patent legislation on the conduct of clinical and field trials involving pharmaceuticals in the UK. Comments are requested by 31 July 2011.

EU Patent – Spain and Italy

OHIM press release, 7 June 2011

http://oami.europa.eu/ows/rw/news/item1947.en.do

Italy and Spain have lodged a complaint with the European Court of Justice against the plan to go ahead with the EU patent without them.

The EU patent is backed by 25 member states and is being introduced under the "enhanced cooperation" procedure, after failure to obtain unanimity due to opposition to the proposed language scheme (English, French and German) from Italy and Spain.

TRADE MARKS

WIPO – domain name "champagne.co"

Comité Interprofessionnel du vin de Champagne v Steven Vickers, Case DCO2011- 0026, 21 June 2011

The Comité Interprofessionnel du vin de Champagne (CIVC), which represents Champagne producers, has failed to secure the transfer of the domain name "champagne.co" from the defendant.

Under paragraph 4(a)(i) of the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy, a complainant has the burden of proving the following:

"That the disputed domain name is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark or service mark in which the complainant has rights."

The WIPO Panel accepted that CIVC had rights in "Champagne" as a protected designation of origin (PDO) or geographical indication. However, as PDOs and geographical indications were outside the scope of the UDRP, CIVC had to show that its rights qualified as an unregistered trade mark to satisfy paragraph 4(a)(i).

The Panel said that the problem was that, while a trader may in appropriate circumstances have recourse to the English law of passing off to protect unregistered rights which it has in a trade mark or service mark, the converse does not necessarily apply: the fact that a trader might have a right to sue in passing off does not necessarily imply that the trader holds an unregistered trade mark or service mark.

In this case, the Panel was not satisfied that CIVC had shown that its rights in "Champagne" constituted an unregistered trade mark right that would satisfy paragraph 4(a)(i).

The Panel noted that it is generally accepted that, to be a trade mark, a sign must be capable of distinguishing the goods or services of an individual undertaking from those of other undertakings. It seemed to the Panel that a geographical indication per se did not distinguish the wine of one champagne producer from the wine of another, and so did not fulfill this fundamental function of a trade mark.

A geographical indication is essentially designed to achieve a somewhat different purpose, namely to speak fundamentally of the quality and reputation of the goods produced according to certain standards in a specific geographic area, but not of any particular or individual trade source as such.

The Panel said that none of the four administrative proceedings in which CIVC succeeded in having "champagne-related" domain names transferred to it, assisted it in this case. The Nominet Policy applicable in CIVC v. Jackson permitted a complainant to rely on rights in a "name" (as well as in a trade mark), and it was on the basis of rights in a "champagne" name that CIVC succeeded. The .ie Policy appeared to be even broader in scope, permitting a complainant to rely on (among other things) a geographical identification. The French and Belgian domain name dispute resolution policies did not appear to have restricted the requirement to ownership of a trade mark or service mark, as the UDRP does.

In view of the Panel's findings, it was unnecessary for the Panel to address the issue of whether the respondent has any rights or legitimate interests in respect of the disputed domain name.

It was also not strictly necessary for the Panel to make any finding on the issue of whether the disputed domain name had been registered and was being used in bad faith. However, the Panel noted that it would also have found for the respondent on this issue.

COPYRIGHT

Court of Appeal - royalty rates for broadcasting music videos CSC Media Group Ltd v Video Performance Ltd, [2011] EWCA Civ 650, 27 May 2011

The Court of Appeal has allowed an appeal against a High Court decision concerning the royalty rates payable for broadcasting music videos. The High Court had previously allowed an appeal against the Copyright Tribunal decision.

The Tribunal had concluded that the rate should be 12.5% of gross revenue, subject to deduction of advertising and other costs. It ruled that 30% of the anticipated royalty would be a fair proportion to pay in advance. (See August/September 2009 Bulletin).

The High Court held that the Copyright Tribunal had not given sufficient weight to the terms of other comparable licences, in particular a licence between Video Performance Ltd and BSkyB, which set a rate of 20%. This was contrary to section 129 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The correct approach should be to start with the most relevant comparable licence and adapt it to the circumstances of the case. (See August/September 2010 Bulletin).

In allowing the appeal, the Court of Appeal said that the High Court had taken an unrealistic and unjustified view of the Tribunal's reasoning. The Tribunal's findings of fact concerning the music-video market were capable of supporting its conclusion about the royalty rate and it had taken into account the BSkyB licence as a comparator, although this could have been made more explicit in its conclusion.

The court said that the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 were not so prescriptive so as to impose a particular analytical structure and methodology on the Tribunal, as proposed by the High Court.

The court suggested that in future, before beginning a formal appeal, a request could be made to the Tribunal for clarification of its decision in appropriate cases.

ECJ - "fair compensation" for private copying

Stichting de Thuiskopie v Mijndert van der Lee and others, Case C-462/09, 16 June 2011

The ECJ has ruled on the meaning of "fair compensation" for private copying under the Copyright Directive in the context of distance selling.

Article 5(2)(b) of the Copyright Directive permits member states to allow private copying as long as they ensure that there is "fair compensation" for rights-holders.

It is now legally possible to make private copies in all EU countries with the exception of the UK and Ireland. Out of the 25 EU member states with a private copying exception, 23 have introduced a system of private copying levies (Luxembourg and Malta being those without). Although the private copying exception has not been introduced in the UK, this judgment is relevant to UK companies that are distance-selling to member states which have imposed this private-copying levy.

Opus was a company based in Germany which sold blank media via the internet. It targeted Dutch consumers, in particular. Opus did not pay a private copying levy either in the Netherlands or in Germany. Nor did the cost of the reproduction media sold by Opus include a private copying levy.

Under Dutch law, the manufacturer or importer of the item used for reproduction is responsible for paying the private copying levy. The Dutch collecting society argued that Opus should be regarded as the 'importer' and, consequently, responsible for paying the private copying levy. Opus argued that, under the sales contract, the Dutch purchasers are the importers.

The Dutch court referred questions to the ECJ concerning who should be regarded as owing "fair compensation" under Article 5(2)(b).

The ECJ held that the final user reproducing a protected work on a private basis is, in principle, the person responsible for paying the fair compensation. However, it is open to the member states to establish a private-copying levy chargeable to the persons who make reproduction equipment available to the final user, since they are able to pass on the amount of that levy in the price paid by the final user.

It is for the member state which has introduced a system of private-copying levies chargeable to the manufacturer or importer of media for reproduction of protected works, to ensure that the authors receive the fair compensation. The fact that the commercial seller of reproduction equipment is established in a different member state to that of the purchasers does not affect that obligation. Where it is impossible to ensure recovery of the fair compensation from the purchasers, it is for the national court to interpret national law to allow recovery of that compensation from the person acting on a commercial basis.

ECJ – remuneration for public lending

Vereniging van Educatieve en Wetenschappelijke Auteurs (VEWA) v Belgische Staat, Case C 271/10, 30 June 2011

The ECJ has ruled on the meaning of "remuneration" in the Lending Directive. The reference from the Belgian court for a preliminary ruling in this case concerned the interpretation of the concept of 'remuneration' paid to copyright holders in respect of public lending, as set out in Article 5(1) of Council Directive 92/100/EEC on rental right and lending right and on certain rights related to copyright in the field of intellectual property (now Article 6(1) of Directive 2006/115/EC).

Article 5(1) states:

"Member States may derogate from the exclusive right provided for in Article 1 in respect of public lending, provided that at least authors obtain a remuneration for such lending. Member States shall be free to determine this remuneration taking account of their cultural promotion objectives."

The Court ruled that Article 5(1) precludes legislation, such as that at issue in this case, under which the remuneration payable to authors in the event of public lending is calculated exclusively according to the number of borrowers registered with public establishments, on the basis of a flat-rate amount fixed per borrower and per year. The court said that the remuneration for public lending had to represent an adequate income for authors; it could not be a merely symbolic amount.

The amount of the remuneration should correlate with the extent to which the works were made available (and hence with the extent of the harm to the copyright). This meant taking into account the number of borrowers registered with a particular establishment, and the number of protected works that it made available to those borrowers. The system established under Belgian law did take the number of borrowers into account, but not the number of works. It did not, therefore, represent adequate income from the copyright works that were being exploited.

The Belgian law provided that the flat rate was payable only once per borrower, even if that borrower was registered with several different lending establishments. This had the effect of almost exempting many lending establishments from paying any remuneration. Previous case law had held that member states could only exempt a limited number of lending establishments (Commission v Spain, Case 36-05).

In the UK, the remuneration system for public lending is based on the number of times a particular work is borrowed.

Advocate General Opinion

Phonographic Performance (Ireland) Limited v Ireland and others, Case C-162/10, 29 June 2011

Advocate General Trstenjak has given her opinion on the right of performers and record producers to remuneration under the Rental Directive for recordings played in hotel bedrooms, in a reference from the Irish High Court.

Article 8 of the Rental Directive (2006/115/EC) provides that:

"1. Member States shall provide for performers the exclusive right to authorise or prohibit the broadcasting by wireless means and the communication to the public of their performances, except where the performance is itself already a broadcast performance or is made from a fixation.

2. Member States shall provide a right in order to ensure that a single equitable remuneration is paid by the user, if a phonogram published for commercial purposes, or a reproduction of such phonogram, is used for broadcasting by wireless means or for any communication to the public, and to ensure that this remuneration is shared between the relevant performers and phonogram producers. Member States may, in the absence of agreement between the performers and phonogram producers, lay down the conditions as to the sharing of this remuneration between them."

Article 10(1)(a) provides that Member States may provide for limitations to the rights in respect of private use.

The Irish court referred questions to the ECJ concerning:

- whether such a right arises where a hotel operator provides televisions and/or radios in guest bedrooms to which it distributes a broadcast signal. The answer depends on whether the operator uses the phonograms contained in the radio and television broadcasts for communication to the public;

- whether such an operator also uses those phonograms for communication to the public where it does not provide radios or televisions in the bedrooms, but players and the relevant phonograms; and

- whether a Member State which does not provide for a right to equitable remuneration may rely on the exception under Article 10(1)(a) in respect of private use.

The Advocate General proposed that the Court answer the questions referred as follows:

(1) Article 8(2) of the Rental Directive should be interpreted to the effect that a hotel or guesthouse operator which provides televisions and/or radios in bedrooms to which it distributes a broadcast signal -uses the phonograms played in the broadcasts for indirect communication to the public.

(2) In such a case, the Member States are required to provide for a right to equitable remuneration vis-à-vis the hotel operator even if the radio and television broadcasters have already paid equitable remuneration for the use of the phonograms in their broadcasts.

(3) Article 8(2) should also be interpreted as meaning that a hotel operator which provides its customers, in their bedrooms, with players for phonograms other than a television or radio and the phonograms in physical or digital form -uses those phonograms for communication to the public.

(4) Article 10(1)(a) should be interpreted to the effect that a hotel or a guesthouse operator which uses a phonogram for communication to the public does not make private use of it and an exception is not possible even if the use by the customer in their bedroom has a private character.

DESIGNS

Patents County Court – unregistered design right

Albert Packaging Ltd and others v Nampak Cartons & Healthcare Ltd, [2011] EWPCC 15, HHJ Birss QC, 2 June 2011

The Patents County Court has held that the claimants had design right in the shape of their carton, but that it had not been infringed by the defendant

This was an action for infringement of unregistered design right relating to cartons used as packaging for tortilla type wraps. The claimants' case was that they designed a new kind of carton for wraps in 2005 and started manufacturing those cartons for Sainsbury in 2006. The cartons were supplied via an intermediary company. In 2008 the intermediary chose to move to the defendant (Nampak) to supply a wrap carton product instead. The claimants claimed that this new wrap carton product of Nampak's was an infringing copy of the claimants' design.

Nampak denied infringement and also challenged the subsistence of unregistered design right on the grounds that the design fell within the exclusion under section 213(3)(a) of the CDPA for a method or principle of construction or, alternatively, that the design was commonplace in the design field in question under section 213(4) of the CDPA.

The judge said that there are various different ways of representing the claimants' design. Packaging designers create the designs by drawing a plan of the cardboard which will be used to make the finished carton. The plan shows elements such as cuts and creases in colour. The design can also be described to some extent by a list of features and also by elevation diagrams of the carton in its filled state.

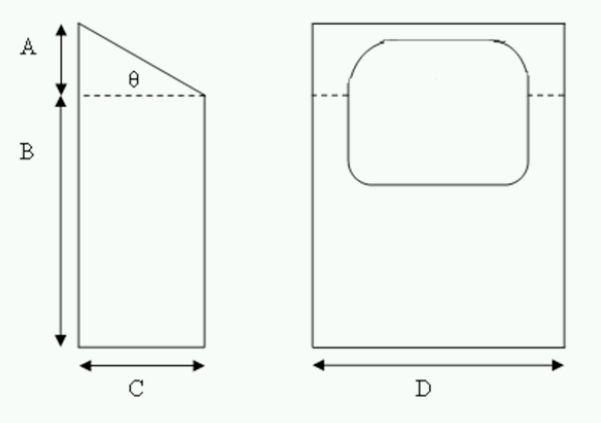

Below are representations of a side and front elevation of the claimants' carton in its assembled state which the judge prepared for this judgment. (They are not to scale and the dimensions and proportions are only rough).

Dimensions A + B determine the height of the carton, dimension C determines its depth and dimension B on its own determines the height of the front vertical panel. Dimension D is the width of the carton. The angle of the front sloping panel to the horizontal is θ. To the nearest mm (or degree), the claimants' dimensions are A = 35mm, B = 95mm, C = 52 mm, D = 104 mm and θ = 34°.)

The claimants defined the design in which they claimed unregistered design right in three ways:

(1) The shape of the carton in assembled form;

(2) A generally rectangular box save in that the top face slopes downwardly from the rear face to the front face, there being a window extending from the sloped top face onto the front face;

(3) The distance from the shoulder of the pack to the top of the back panel, along the back panel, is 35mm regardless of the length or width or depth of the pack.

The judge held that the claimants had design right in the shape of their wrap carton in assembled form (first definition), but that it had not been infringed by the defendant, for the following reasons.

Regarding the exclusion of a method or principle of construction (which was not raised as an argument in relation to the first definition of the claimants' design) the judge said that to give the claimants a monopoly in a single dimension (the third definition) was too general. This definition was a concept and was excluded from protection.

Although the second definition was less general than the third one, it was held that this still fell foul of s213(a) because it was ultimately nothing more than a definition of a concept rather than a definition of a design with a specific, individual appearance. To accept this definition would be to give the claimants a monopoly akin to a patent monopoly (albeit limited to cases of copying) in any pack which satisfied that definition. But packs which still satisfy that definition will have very different appearances – there is no restriction on the relative dimensions.

The second and third definitions were also found to be commonplace in the design field of carton design.

On the basis of the relevant authorities, the approach taken in assessing infringement was as follows. Firstly, the judge considered whether the similarities between the Nampak product and the Albert Packaging design (as well as the possibility of access) raised an inference of copying? In considering that, the judge said that he would bear in mind that functional features may be similar because they are performing a function, not because of copying. If an inference is raised, then he would consider what explanation Nampak put forward. Finally, he would compare the Nampak product and the design objectively - the relevant article must be produced exactly or substantially to the design for there to be infringement.

The judge found that the cartons were very similar and raised an inference of copying. In relation to Nampak's explanation of the design history, the judge found that they did design a carton in 2005 which provided one source of the designs in issue in their case. However the claimants' design was also another source of ideas which fed into the carton design alleged to infringe. The judge therefore rejected Nampak's contention that their product had been designed independently.

However, the judge stressed that it does not follow that Nampak's product necessarily infringes. When it comes to comparing the article alleged to infringe with the claimants' design in a case like this one, in which the article was in fact derived from multiple identifiable sources, it must be necessary to identify how much of the design of the article in question can be said to derive from the claimants' design.

The judge found that only a trio of dimensions of the side panel were derived from the claimants' design, and that looked at as a whole, what the Nampak products owed to the claimants' first design definition (the shape of the carton in assembled form) was not a substantial part of that design and did not infringe. Other similarities derived from a source independent of the claimants.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.