![]()

Participation in defined benefit pension schemes can have far-reaching consequences for charities.

In the preceding article, we explain that a merger may be the best way for a charity facing a substantial, long-term reduction in income to avoid insolvency. However, past or current participation in defined benefit (DB) pension schemes could be a potential bar to a successful merger.

Defined benefit schemes

A DB pension scheme is one in which pensions paid are based on the retiring employees' salaries, such pensions being paid until the retiree (and sometimes, their spouse) dies.

Recent and forecast increases in longevity have made these schemes simply too expensive for employers. As a result, except in the public sector, final salary schemes have largely been replaced by defined contribution schemes or, in some cases, DB schemes based on average salary.

While longevity has been increasing since the 19th century, the rate of increase has risen significantly over recent decades.

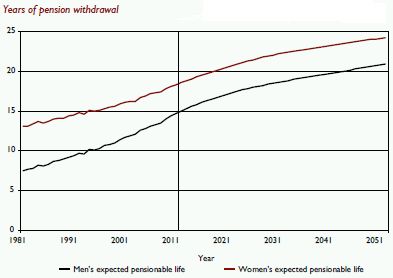

Data from the Office of National Statistics shows that in 1981 a man who joined a pension scheme at the age of 25 would expect to draw his pension for 7.5 years, by 2012 this has increased to 15 years and by 2042 is forecast to increase to over 20 years. Similar trends also apply to women. These trends are shown in the graph below.

The result of these trends has not only been the closure of DB schemes, but also for many schemes to be in deficit. That is, the amount that the scheme expects to pay out is much more than the assets in the scheme. Such deficits can cause significant issues for charities, particularly those looking to merge.

Financial accounting

Financial Reporting Standard Number 17 requires charities to measure their DB pension surpluses or deficits and reflect these in their balance sheets. While this will highlight the existence of a deficit, caution should be used in interpreting this figure: the amount recognised is calculated in accordance with accounting rules and does not actually represent the amount which will be paid in the future.

However, an accounting deficit is usually indicative of a 'real' deficit in the scheme. If there is a significant deficit which has not been addressed, it may raise an issue over the solvency of the charity and its ability to continue as a going concern. Trustees will need to consider how funding a deficit may impact on future budgets. Sometimes providing the scheme with security (perhaps over a building) can help to reduce the cash funding burden.

Leaving a multi-employer scheme

Many charities also participate in multiemployer schemes and the deficits relating to these schemes are not always recorded in charities' balance sheets. Therefore, there may be substantial liabilities of which trustees are unaware.

While a charity continues to have employees in such schemes, there is usually no obligation to make cash payments, other than the normal contributions. However, if an employer leaves a multiemployer scheme, under section 75 of the Pensions Act 2004, the scheme trustees will normally demand that the employer pays off the deficit. Broadly, an employer leaves a scheme when it no longer has any employees in the scheme. This will happen if the relevant employees leave, are made redundant or retire. There are some ways to alleviate the immediate payment but these are complex and require professional advice.

Finally, one nasty tweak is that an employer might have participated in a scheme which had a DB section and a defined contribution section. It might be that the charity no longer has any employees in the DB section and views the scheme as simply a defined contribution scheme. However, any past deficits relating to the DB section will still be an obligation of the charity.

Merging

A key part of any merger is the financial plan which is used to assess the viability of the merged charities. Staff costs are usually a key component of expenditure and pension scheme contributions form part of these costs. Looking to the future, trustees will need to consider the impact of auto-enrolment, whereby all staff will be automatically enrolled in employer pension schemes. Auto-enrolment is being phased in over the next few years, beginning with larger employers in 2012. We expect this to result in increases in employer pension contributions.

If a charity borrows money, the need to fund any pension deficit may also have an impact on existing borrowing, compliance with loan covenants and the charity's ability to raise funding in the future.

A merger may also trigger the need to assess the debt owed to a pension fund under section 75 of the Pensions Act 2004 and possibly pay the debt or make additional or accelerated scheme contributions. In the worst case scenario, an annuity might have to be purchased from a regulated insurance company. If charities are merging due to financial pressure, any accelerated or additional payment requirement may be enough to scupper the plans to merge. If this is the case then winding up may be the only remaining option.

The CFDG has produced some excellent work in its publication The Charity Pension Maze which highlights the particular problems of charities and pension deficits.

|

Perils of a multi-employer scheme Most multi-employer schemes are public sector schemes (for example, NHS, Local Government Pension Scheme, Teachers' Pension Scheme) or schemes with a large number of members. However, for charities in a multi-employer scheme with few active employers, the experience of the Wedgwood Museum charity provides a grim warning of the perils of such an arrangement. The museum had five staff in the 7,000 member Wedgwood pension scheme. When the Wedgwood companies went into administration, as the only entity not in administration, the museum became liable for the entire scheme deficit – a modest £134m. As a result, the museum was also put into administration and the High Court has ruled that the collection must be sold, with the proceeds to be put towards the pension deficit. |

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.