Foreword

It's a challenging time for tax leaders, who must cope with geopolitical uncertainty, evolving and often fragmented regulations, a shortage of tax talent, and rapid technological change.

Global tax policy is in a more dynamic state than ever, with many jurisdictions striving to promote responsible tax behaviors, protect their tax bases, and compete for investment. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's (OECD) Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) 2.0 measures on global minimum tax have been supported by more than 140 countries. Tax incentives are also being used to attract investment in green technologies and renewable energy to address climate change.

However, these efforts are now under challenge by the US government, and the pendulum that had swung towards cooperation on corporate tax policy may be swinging back towards competition. Tax operating models are under significant stress, internally and externally, and significant investment and transformation are needed to cope with the journey ahead.

Generative AI (Gen AI) is an essential tool with growing usage, bringing exciting opportunities to redefine business processes, improve productivity and compliance, and free up tax professionals for higher-value work. But, this can only happen through retraining to adapt to new roles and the introduction of new tax workflow processes to ensure high-quality, verifiable outcomes.

The report highlights three strategic imperatives that tax leaders should prioritize to create value for their organizations. We'll also outline key steps needed to deliver this value and help enable organizations to achieve competitive advantage.

Introduction

Strategic imperatives for tax leaders

With so many developments and trends reshaping tax policy and business practices across the globe, it's no wonder many tax leaders may be unsure where their energy and attention will produce the biggest impacts.

Externally, tax bases are under threat from demographic changes, trust in governments and tax systems is diminishing, tax talent is in short supply, and the global tug-of-war between tax cooperation versus competition continues. Internally, cost-cutting pressure is intensifying amid widespread finance transformation and rapid technological change.

To help tax leaders decide the best path forward for their teams and their organizations, three key areas that tax leaders need to understand and manage are:

In light of these forces of change, organizations should not only adapt but also embrace innovation. By proactively responding to these evolving demands, businesses can strengthen their tax functions, ensuring they are not only resilient in the face of challenges but also positioned for future success.

The discussion in these pages seeks to provide an informative and insightful analysis of how these developments are influencing tax functions and how the business environment and direction of tax policy is likely to evolve in the years to come. We also highlight some important actions for tax leaders to consider as they work to position their teams for success in the new global reality.

Tax policy

Coping with a dynamicand unpredictable tax environment

Evolving regulations and fast-changing world events are putting significant pressure on tax functions. In the KPMG 2024 CEO Outlook, respondents identified the business issues likely to affect their organization's prosperity over the next three years. A significant majority, 79 percent, agree or strongly agree that new emerging trade regulation will negatively impact their organizations, while 56 percent express similar concerns regarding regulatory demands.1

Faced with potential new tariffs (and a subsequent trade war), rising energy costs, and highly complex and fast-changing local and international tax regimes, companies are rethinking their global footprint and supply chains. As Christian Athanasoulas, Global Head of International Tax and M&A Tax, KPMG International, notes: "Businesses may have chosen their manufacturing base for its low labor costs, or to take advantage of lower-tax and R&D incentives. The threat of tariffs, along with new global minimum tax rules, could undermine such benefits."

The tariffs could have a significant adverse impact on global trade, with consequent declines in global GDP and living standards. There has also been a failure to gain full consensus on most elements of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) agenda through the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Inclusive Framework, with global minimum tax the only real area of agreement. Initiatives from the United Nations (UN) increase the possibility of many developing countries placing withholding taxes on cross-border services — which causes further questions about where companies locate.

Governments have always sought to optimize their tax revenues while maintaining an environment that is friendly to businesses and investors. However, the challenge of funding public services in more developed economies has been exacerbated by aging populations and a falling taxpayer base. In Europe, for example, the mean age is 40 in the UK and almost 47 in Germany, compared to 19 in Nigeria.2

With the COVID-19 pandemic having placed further strain on governments' balance sheets, corporate tax leaders are maintaining a close watch on future tax decisions that could impact their businesses — which adds to the broader uncertainty over the tax burden. According to the KPMG 2024 CTO (Chief Tax Officer) Outlook, the number one challenge faced by tax functions is keeping up with complex and evolving domestic legislation and regulations (50 percent).3

Tax function challenges in the current tax landscape

Note: Survey participants may select up to three. Source: 2024 KPMG Chief Tax Officer Outlook, KPMG in the US, 2024.

For instance, when a tax team is modeling the implications of an international M&A transaction, it cannot accurately predict the likely tax rate due to comprehensive legislative and regulatory changes across the globe.

The ongoing challenge of tax on digital business

Governments are particularly keen that new, digitalized businesses — some of whom have shifted profits legally to low- or no-tax jurisdictions — pay appropriate taxes in the locations where they make their profits.

Tax regimes have traditionally been oriented towards physical assets, making it relatively more straightforward to tax wages, sales of goods and services, bank deposits and mineral resources where they are located. However, the value of new services and products is increasingly rooted in highly mobile software, patents, trademarks and other intangibles.

For example, should the value of a new Gen AI app be taxed in California, where it was developed? In the UK, where the servers are located? Or in the countries where it is marketed and licensed? If the value for tax should be allocated across all of these countries, what factors would decide how, and by whom, this allocation is determined?

One of the challenges is timing. The complete business life cycle for digital enterprises does not occur simultaneously, which forces companies to create plans for emerging requirements while also addressing the difficulties presented by existing tax systems and regulations.

When asked which factor has had the greatest impact on their organization within the last year, 60 percent of respondents to the KPMG Global Tax Benchmarking Survey cite "tax reform" with a specific reference to digital taxes.4 As Lachlan Wolfers, Global Head of Indirect Taxes, KPMG International, explains, "Digital services taxes (DSTs) typically apply to online advertising, online marketplaces and social media, but not to online retailers selling their own products, streamers of proprietary content, or providers of cloud computing services. However, DSTs are still evolving and in the future are likely to encompass the full range of digital services."

Commenting on DSTs, Grant Wardell-Johnson, Head of Global Tax Policy, KPMG International, notes, "The failure to reach agreement on tax measures involving the digital economy may result in the proliferation of DSTs. Given the importance of the US tech industry, this is likely to result in retaliatory action from the US in the form of increased tariffs."

E-invoicing is on the march

According to the KPMG report The future of indirect taxes to 2030, the main objective of electronic invoicing (e-invoicing) is to enhance value-added tax (VAT) compliance and reduce the VAT gap. However, in future, tax authorities are expected to expand the usage of e-invoicing, loosely following a four-phase approach:

- Phase 1: Utilize collected data to enhance VAT compliance through data matching, which ensures that the VAT output tax matches the VAT input tax of the business customer.

- Phase 2: Leverage the data collected through e-invoicing and require taxpayers to reconcile their VAT returns (and be able to explain deviations).

- Phase 3: Use data gathered through e-invoicing to pre-fill VAT returns.

- Phase 4: Employ the data collected through e-invoicing to enhance compliance across other taxes, including transfer pricing and corporate income tax.

"Companies will no longer have the luxury of submitting indirect tax returns, because electronic data, on a digitized invoice, is going straight to a tax authority, who will create a VAT return," says Lachlan Wolfers, Global Head of Indirect Taxes, KPMG International. "This means they won't have time to correct any errors as the tax authority will already have access to that data. So, getting it right in the beginning is becoming crucial. Consequently, e-invoicing becomes more than a tax issue; it's a business issue that, if not done properly, can create massive business disruption. If the invoice is not compliant, you cannot issue it, which can actually stop all operations."

The evolution of BEPS — where does it go from here?

For the past decade, there have been significant efforts to align the international tax system with the global economy. The OECD has become the forum of choice for countries to develop policies that reshape how businesses are taxed.

A large number of countries have adopted some element of the OECD's Pillar Two framework — or have introduced corporate income tax for the first time. However, the future of BEPS 2.0 remains uncertain. The US government has rejected a number of elements of what it terms the "OECD's Global Tax Deal"5 and is publicly pursuing protective measures, while the position of China and India on Pillar Two remains unclear.

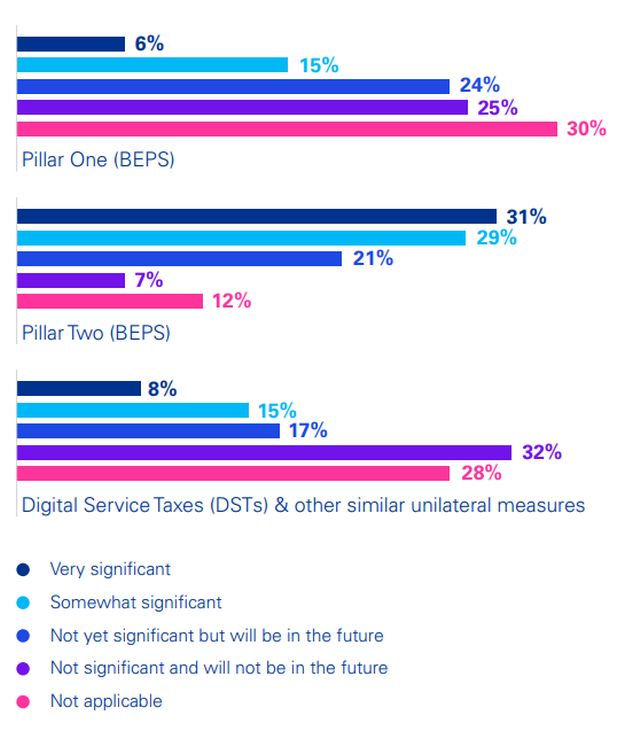

Assessing the impact of international tax rule changes on organizations

Source: KPMG Global Tax Function Benchmarking Research — Ongoing, KPMG International, 2024.

Moreover, the OECD and its Inclusive Framework appear unlikely to finalize a deal on Pillar One, its proposed alternative to DSTs and other similar measures. A renewed focus (and alternative ideas) will be required if DSTs are finally going to be removed. It seems likely that there will be further revisions to the Pillar Two framework by the OECD throughout 2025. Additionally, there are likely to be further developments about 'Amount B' — the OECD's effort to simplify and streamline transfer pricing for marketing and distribution activities.

In the ongoing KPMG Global Tax Function Benchmarking research, which presents the views of tax leaders from large, primarily multinational companies around the world, BEPS Pillar Two is identified as a significant or very significant change facing their organization (60 percent).6

"The additional compliance burden arising from the introduction of the global minimum tax is probably the largest challenge for multinationals in the new tax environment," says Grant WardellJohnson, Head of Global Tax Policy, KPMG International. "This will take many forms, including completion of a global information return, and will involve dealing with revenue authorities on audits — and potentially disputes on uncertain areas."

The UN's zero draft proposal — fragmentation or alignment with BEPS?

Many developing countries lacked faith that the OECD, with its more developed members, is inclusive enough as a forum for renegotiating tax rights. In 2023, 125 primarily developing nations voted in favor of a UN resolution to tackle international tax cooperation at the UN.

The resulting Terms of Reference (ToR) for a framework convention on international tax cooperation was approved by the UN General Assembly in December 2024. The ToR aims to establish a "system of governance for international tax cooperation" and "ensure fairness in the allocation of taxing rights under the international tax system."7 An intergovernmental negotiating committee has been formed to draft the framework convention and two early protocols over the next three years, with the committee expected to complete its work in 2027.

One of the early protocols will focus on the taxation of income generated from cross-border services in an increasingly digitalized and globalized economy. The second early protocol will deal with prevention and resolution of tax disputes. These protocols will require approval by two thirds of voting states.

ESG taxes and incentives cloud the waters

As global efforts intensify to curb harmful emissions and achieve carbon reduction targets, tax policymakers increasingly leverage fiscal measures to drive the transition towards renewable energy. These measures typically manifest as either incentives ("carrots") to promote sustainable practices or penalties ("sticks") to deter environmentally detrimental activities.

In the US, the Biden administration has predominantly embraced a "carrots" approach, as evidenced by the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. This legislation earmarked substantial financial incentives for renewable energy initiatives, projected to catalyze over US$1 trillion in investments. However, under the Trump administration, a shift in this approach may occur, though the implementation of new policies remains uncertain.

On the other hand, Europe has tried to adopt a "carrots" and "sticks" approach, combining incentives and regulations to spearhead climate protection efforts. The European Green Deal, established in 2019 and formalized in 2020, is a roadmap of tax and non-tax policy initiatives to transform Europe into the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. Additionally, in September 2020, the European Union (EU) set a target to reduce emissions by 55 percent by 2030 from 1990 levels.

To meet this target, the European Commission adopted a series of legislative proposals under the "Fit for 55 package," which includes the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). This mechanism imposes tariffs on carbon-intensive imports like steel and cement to mitigate carbon leakage and encourage global climate action. Carbon taxes, functioning as indirect taxes similar to excise duties, are increasingly influencing VAT collection by embedding carbon costs into the taxable supply price.

Moreover, the EU is advancing additional legislative measures, such as the EU Deforestation-free Regulations and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, to facilitate a data-driven transition to sustainability. The EU's funding program further supports this transition, with a seven-year budget dedicated to fostering economic growth, social cohesion, and environmental sustainability through investments in research, infrastructure, and regional development.

Globally, countries like Australia and Canada are also introducing incentives for green investments, while the EU has relaxed state aid principles to accommodate tax concessions. The proliferation of incentives will likely heat up competition for capital worldwide.

As Loek Helderman, Global ESG Tax & Legal Lead for KPMG International, explains, "Companies need to assess their carbon footprint of imported products to determine whether it's more costeffective to produce within the Eurozone. And the list of products is likely to expand to more raw materials over time, which will affect a greater number of organizations."

To view the full article, click here.

Footnotes

1. KPMG 2024 CEO Outlook, KPMG International, 2024.

2. Median and average age in global comparison, World Data Info, December 2024.

3. 2024 KPMG Chief Tax Officer Outlook, KPMG in the US, 2024.

4. KPMG Global Tax Function Benchmarking Survey, KPMG International, 2023.

5. Sam Sholli, "Trump: OECD's pillar two 'no force or effect' in US," International Tax Review, January 21, 2025.

6. KPMG Global Tax Function Benchmarking research — ongoing, KPMG International, 2024.

7. Zero Draft Terms of Reference, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs — Financing for Sustainable Development, June 7, 2024.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.