Inventing is truly a numbers game.

I became reminded of that old truth when speaking with Chris de Armit at my latest Clubhouse event (click here).

Chris has said that he had made thousands of inventions in his lifetime and he still invents every day. That is how it should be.

Inventing by playing it as a numbers game is the prerequisite for minimizing your risks through a controlled cutting of losses. You give up on ideas that do not work out, and focus resources on developing better inventions.

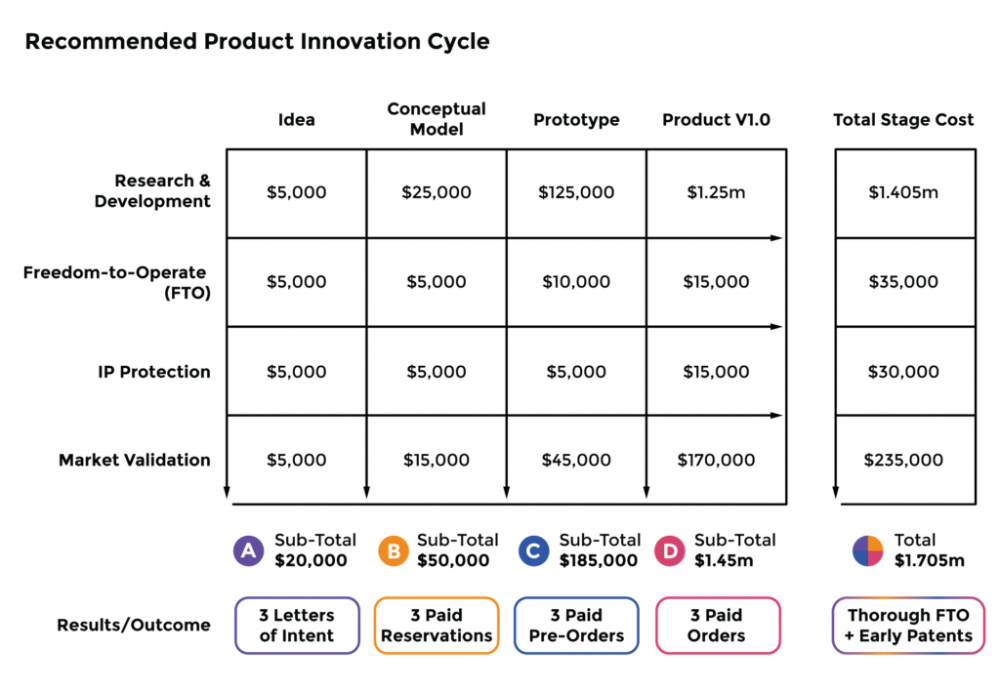

Let's look at an informed inventor. I will use realistic numbers and put them into my 4×4 Innovation Strategy matrix that you find explained in my book "The 4×4 Innovation Strategy" (click here). I have also given public talk about that (click here).

In short words, the 4×4 Innovation Strategy shows the development of an invention with respect to its Technology Readiness Level, from "Idea" over "Conceptual Model" to "Prototype" and to Product 1.0″, while completing the four (4) Innovation Work areas "R&D", "FTO", "IP" and "Market Validation":

Typically, you start by investing $5,000 into R&D at the idea phase. But next, instead of moving horizontally along the X-axis to develop a conceptual model, you stick with your idea, and invest in a $5,000 Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) study. Why do this now? Because it helps you find out, very early on, if you are allowed to do what you want.

Next, you protect your Intellectual Property (IP) with a simple provisional patent application at $5,000.

Then comes your market validation, rather cheaply at $5,000.

At this point, you might be asking, how can you do this without an actual product? Well, you examine your value chain and figure out where your product sits in it. Then, you ask potential customers to give you a Letter of Intent (LoI). This is a simple letter that basically says, "Dear inventor, I like your idea very much. If you will provide a product with this feature, I'm willing to do a prepaid purchase for 100 products."

You should be able to get three Letters of Intent. Show them to potential investors. They will generally say, "Okay, I trust you. You have three Letters of Intent, so this idea is validated. I will give you some money, let's build a conceptual model to see if this idea works."

My Mosquito Trap Project

You may remember that I have once done a mosquito trap project because as you know, I am also an inventor. I have been living in Singapore for over 20 years, and a common seasonal problem that pops up every year is dengue, a mosquito-borne infectious disease. One of my inventions was a mosquito trap to solve this problem. It was a pretty good idea as it turned my property mosquito-free within three weeks, and I was featured in The Straits Times, Singapore's national newspaper, several times.

Here are two of these articles in the Straits Times of 13 December 2014 and 08 February 2015:

What you see above is a prototype of my invention. There is a lot to discuss with respect to prototypes, including when to make one, when to send one, whether the prototype needs to "work-like" the final product or just "look-like" it (or both!). Making a prototype might help you improve your product, uncover even more work-around issues than you have already come up with, and get production quotes for manufacturing. The additional knowledge will encourage you to file more IP.

But please note that I went so far with my own prototypes only after (!) I had tested the market and collected a number of Letters of Intent based on my pure idea.

Example Letters of Intent

I have provided my LoI template here so that you can download it: Letter of Intent to purchase a number of Koobatra Automated Ovitraps

Here are three LoIs of typical end users:

And here are two LoIs from potential industry partners: Lantiq (for the IoT part) and Bayer (for the mosquito fighting part):

NDA and Letter of Intent 190614

Letter of Intent for Koobatra Ovitrap signed

Please feel free to use these LoI´s as templates for your own purpose.

How To Get Letters of Intent

Please note that all the above LoI´s were issued long before the two newspaper articles above were published. I did not need any working prototype for getting these LoI´s!

I have instead used a so-called "sell sheet" for collecting these LoI´s. I could have used a "gee whiz" video instead (click here for more information about that).

A sell sheet or a gee whiz video includes a one-line benefit statement that encapsulates the reason your product idea even exists. Do not assume that anyone will "get it" with a simple verbal explanation of your product. You need to show pictures and an explanation.

Here is the sell sheet that I have used for my mosquito trap:

Yes, you have seen right. I have used the "provisional" PCT patent application that I have filed immediately after I had the idea to build an automated mosquito trap. That is why we file patent applications early: we can freely talk about our inventions without having sleepless nights. And why not showing our provisional patent application to people that are interested in our invention? You don´t even need to request them to sign an NDA for that if you make sure that all pages are stamped with "confidential".

Just to brush up your knowledge: a "provisional" PCT patent application is a regular PCT patent application but without paying the official fees. Check out my Patent Strategy Basic course if you you want to find out more about that filing strategy (click here).

How Letters Of Intent (LOI`s) Will Help Your Innovation

There are many fields in which your collected LoI´s can help you at a later time.

LoI´s will attract investors, especially so-called "Angel Investors". This is what I have written on page 50 of my "4×4 Innovation Strategy" book (click here):

Angel investment occurs during the idea phase. An angel investor funds the development of the conceptual model. The investment amount is about $25,000 to $150,000. Angels get no security except what we call "SAFE", or a "simple agreement for equity", which is typically non-binding and a weak legal agreement. For this reason, investment at this stage is mostly about trust, and angel investors are usually family and friends. Still, savvy angel investors like to see some indicator of past success before putting in their money.

Indicator of success: "getting traction". This means that there are people interested in the idea. As an inventor, you get traction by doing some market validation, and receiving letters of intent from interested customers.

LoI´s makes your story also more believable, it creates trust. I have used my LoI´s to convince the Singapore Straits Times to write about my mosquito trap project.

LoI´s also help you to morph your system along the way because you get a focus on the ultimate customers. I have received valuable input from the people whom I have approached for issuing an LoI to me.

Do I need to tell you more advantages?

Go out to get some LoI´s!

Caution: Better Not Broadcast Your Invention At An Early Stage

Although you have secured a priority right for your idea by filing an early provisional PCT patent application for your invention, you are far from being in a strong position when someone copies your invention. First: a granted patent is not self-executing, you need a court decision if you want to enforce your patent against a copycat. Second: it may take years for your patent application to become granted. Third: patents are territorial. That means that you need a patent for each country where you want to have protection for your invention.

The problem of developing a strategy for filing patent applications with a limited budget is comparable to the problem of a dog marking his territory: you cannot pee at every tree. There are myriads of books out there that explain how certain goals can be achieved when a specific filing strategy is used. It is not my intention to add more to this well-grazed area of patent law. Within any given budget, it is usually easy to find a filing strategy that works while costs are kept down.

That is why you apply common sense when you disclose your invention to others: don´t put it on the Internet and don´t display it at trade fairs before you can pre-sell your product to others.

The 4×4 Innovation Cycle Continues

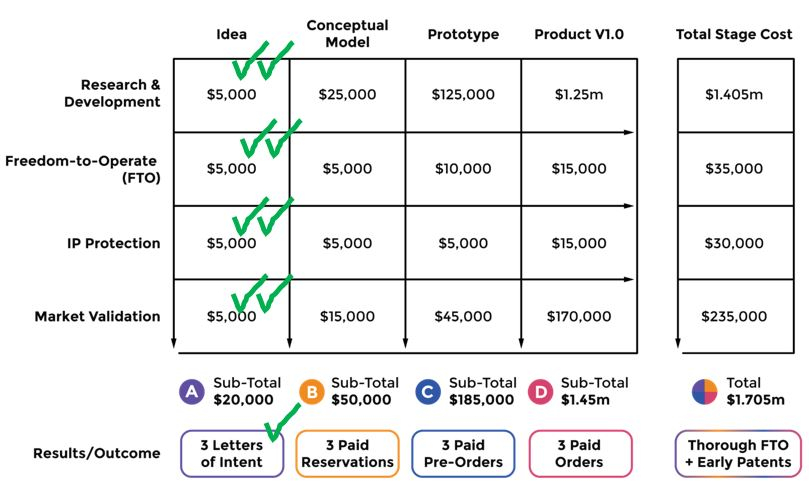

Let´s assume that you have collected three (3) letters of intent (LoI´s) after presenting your invention to interested buyers and cooperation partners. Your 4×4 Innovation matrix looks like this:

You make one green tick once you have started a specific innovation task, and you put in a second green tick after you think that you have completed it. And you provide a green tick for the result or outcome of that technology readiness level.

That explains also why the 4×4 Innovation Strategy has nothing to do with the so-called "stage-gate project management".

This is what Wikipedia says about "stage-gate" (click here):

A phase-gate process (also referred to as a stage-gate process[1] or waterfall process) is a project management technique in which an initiative or project (e.g., new product development, software development, process improvement, business change) is divided into distinct stages or phases, separated by decision points (known as gates).

At each gate, continuation is decided by (typically) a manager, steering committee, or governance board. The decision is made based on forecasts and information available at the time, including the business case, risk analysis, and availability of necessary resources (e.g., money, people with correct competencies).

Stage-gate is bureaucratic and it does not work. Here is what Chris DeArmitt writes about "Stage-Gate" in his book "Innovation Abyss" (p. 50, click here for downloading the book):

What is Stage-Gate or Phase-Gate? It is a system for project management which is claimed to help you with your innovation process by introducing structure. That sounds excellent in theory. Apparently people buy the idea, literally, because 80% of the Fortune 500 use it. They each paid up for a virtually identical system to help them structure their efforts.

You would think that, with that amount of money spent, it must be very effective and well proven. So, what do you find when you look at innovation project effectiveness over the last few decades, as Stage-Gate has swept the market? We find that instead of an improvement, the launch rate for successful new products has actually declined. That means that a lot of money has been spent on software and manuals only to get worse results. Even more money has been spent on training, data input, meetings and tracking. All for nothing, or, actually, less than nothing, i.e. negative results. Here are the findings on the effectiveness of Stage-Gate ...

In contrast to a stage-gate process, my 4×4 Innovation Strategy matrix focuses on the main points that you need to touch before you move on with your invention. The person who is in charge of that innovation – the so-called "Innovation Effectuator" – has the full power to make decisions about advancing the project, and about morphing the initial idea into a Product 1.0 that is acceptable to the deciders in the target market.

That is NOT a stage-gate way of managing innovation.

The 4×4 Innovation Matrix Continues On

Next, you will go through the cycle again for the conceptual model phase. R&D at $25,000, FTO study at $5,000, protecting your new IP (the additional inventive concepts from the conceptual model) at $5,000, and again, market validation. You will spend about $15,000 to knock on doors. You will send LinkedIn messages, call people, go to trade fairs, and talk with potential buyers. If you talk to the right ones, you can get three paid reservations for your as yet unfinished product. This is actual money on the table!

Now, let's assume you take a loan from the bank, or from your grandmother, or you get an investor who believes in your idea. With these resources, you can start the cycle for the prototype phase. R&D will be more expensive at $125,000, followed by FTO at $10,000 (now you are covering more countries, so it will cost more), followed by IP protection for additional features at $5,000, and again, market validation. This time you spend $45,000 to hire a professional to knock on the doors. This is usually somebody who has both market knowledge and a great network in the target market. Your goal? Three paid pre-orders. Again, this is real money on the table.

So far things have been going well: you have three paid pre-orders and perhaps $200,000 sitting in the bank. Now it's time to be bold again. You take out a loan for $800,000, so that you have $1 million with which to enter the product v1.0 stage. The R&D will cost about $1.25 million, but you feel pretty secure about spending this amount, because you know that there are customers out there willing to buy it. Similarly, the FTO is only another $15,000, because by now after sufficient market validation at the previous stages, you know who is interested in your product. Your IP will cost about $15,000 to update it to a PCT application. And finally, marketing the product to your identified targeted customers will cost about $170,000. The result? Three paid orders, on top of the three pre-paid orders achieved at the prototype stage.

You are in business! You have successfully sold your product to six different people, and you have a steady stream of revenue. Your positive cashflow means that you can go straight into production without worrying about your finances.

If you look at the 4×4 matrix, your innovation strategy has been to go through all 4 innovation tactics in order, for each and every product development phase.

What Happened To My Mosquito Trap

My computer-controlled mosquito trap prototype effectively punched a hole into the dengue map of Singapore. The prototype was so good that while a school only 100m down the road had 300 dengue cases, my house and my immediate neighbors' houses were mosquito-free. Almost every house in our area had a few Dengue cases. The years 2014 and 2015 were bad Dengue years for Singapore.

But my mosquito trap invention did not make it into a successful product or service. It was killed by Freedom-to-Operate (FTO).

At the idea and conceptual model phases, I did quick FTO studies to look for existing patents protecting the inventive concepts. I did not find any. So no issues of IP infringement. I was very pleased and eagerly went on to develop my simple prototype that is shown in the above newspaper articles. As an inventor, I got really excited about the positive results of running my mosquito trap prototype. But as a patent attorney, I was still cautious. I knew I must do a broader, more comprehensive FTO before putting in more money to develop an actual product v1.0.

And what did I find out? Singapore has a Vector Control Act that forbids the operation of my type of mosquito trap without a special safety license. Keeping this license up would increase the cost to $600 per trap per month, and there was just no business case for it. I brought my prototype data to the National Environment Agency (NEA), and while the results were good, my trap design was not considered safe to operate without the license. A good product was only part of it; I had to guarantee regulatory compliance.

Also, there were other concerns from a public health standpoint. It was not right to allow my mosquito trap because selective adoption has potential negative consequences. Imagine that a customer is willing to buy the trap, but they later terminate their maintenance contract that services the trap. The mosquito trap would stop working well and probably even promote breeding of new mosquitoes. Suddenly there would be more mosquitoes than before, creating a breeding hotspot and increasing the neighborhood's chances of dengue. As an engineer, I could develop the product. But would I be able to ensure the availability of maintenance services, or enforce ideal customer behavior? Would I be able to ensure widespread and systematic adoption to mitigate the risks? It took me some time to understand that successful market entry was not about product and IP alone, but includes issues of cost, regulations, and in this case, public health considerations.

The Importance of FTO

IP is not enough. FTO studies can discover obstacles that are blind spots. And because these obstacles can change with the business environment, FTO should be done at all phases of product development. Never assume that you know everything; it is better to engage experts to conduct due diligence to identify these obstacles.

Personally, I think that FTO is one of the most complex topics in innovation, because it can be so broad and vague and still have a crucial impact on the success or failure of your innovation.

Conclusion

If you are an inventor or if you work for one, then understand how innovation works.

Learn to think about innovation within the 4×4 Innovation Strategy matrix.

Do not advance your innovation to the next Technology Readiness Level before you have completed all Innovation Work areas for your current T3echnology Readiness Level.

Do not underestimate FTO and do not skip the Market Validation steps. Both can kill your innovation, whether you are a Start-Up or a Multi-National Company (MNC).

You find templates for LoI´s in my article above.

Martin "Strategic" Schweiger

Originally published 29 May 2021

IP Lawyer Tools by Martin Schweiger

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.