The strong demand for minerals and metals and its concomitant effect on prices have prompted debates in resource-rich countries concerning the share of economic rent the state should retain and the structure and appropriate level of mining royalties required to achieve its financial and economic objectives. Canada is no exception. In Quebec, a new mining royalty scheme was adopted in 2010. Although there is general support for the new scheme, its implementation has not quelled the public debate.

In an effort to refocus the debate on a rational examination of the factors that must inform an efficient mining royalty scheme, SECOR-KPMG and Fraser Milner Casgrain ('FMC') have, in a recently published report ('Report''), compared the royalty scheme presently in effect in Quebec to three other royalty schemes that have been proposed in order to determine their likely impact, taking into account the characteristics of the Quebec mining sector and its relative position globally1,2. The Report provides an analytical framework to assess and compare various royalty schemes in order to gain a better understanding of their impact on profitability as well as on the potential revenues that the Government of Quebec can expect from mining activities. It also explains the investment decision-making process in the mining industry.

This overview of the Report summarizes the key considerations taken into account in the comparative analysis, the methodology used to derive the potential impact of proposed royalty schemes with respect to the risk/reward equation governing investment decisions in the mining industry and the salient points of the Report.

1. THE QUEBEC MINING INDUSTRY IN A GLOBAL CONTEXT

In 2011, Quebec shipments of minerals and metals amounted to $7.7 billion, placing the Province in the fourth position behind Ontario, Saskatchewan and British Columbia with about 16.1% of total Canadian shipments3. With eleven large-scale mines currently in operation, the Quebec mining sector represents less than 1% of global mineral production and, therefore, it is relatively marginal on an international scale. Looking to the future, four of the world's 200 large-scale projects are located in Quebec, two of which being iron mines projects4.

Quebec is a good place for mining operations and a promising location for the development of new mines. There coexists in its large territory regions with known potential and several others with undetermined potential, such as the Plan Nord territory, where the likelihood of discovering various mineral deposits that would be competitive on a global scale is generally considered a distinct possibility. The development of large hydroelectric dams over the past 25 years has equipped the James Bay territory with road, electricity and airport infrastructures which now give year-round access to this vast region. But there is much more to it. The availability of professional and technical personnel, a trained workforce and the quality of its geological database and modern public geosciences infrastructure constitute major advantages. Moreover, Quebec offers a stable environment conducive to business. According to the Fraser Institute, Quebec ranked as the 5th most attractive mining jurisdiction worldwide in its 2011/2012 Survey of Mining Companies5.

The relatively small size of the Quebec mining sector at the global level is due to various factors, including the size and average low grade of the mineral deposits, the relatively harsh climate conditions that prevail, the infrastructure deficit to access remote deposits in the northern part of the Province and the greater distance from the large Asian markets relative to its main competitors. The combination of these factors drives most Quebec's mines into the third and fourth quartile in terms of production costs and, therefore, renders them more susceptible to the vagaries of world commodity markets. The iron ore and gold mining sectors provide a good illustration of the situation and the factors at play. These minerals represented 43% and 17%, respectively, of total Quebec mineral production in 2010 which is the reason the Report is focused on these two mining segments.

1.1 THE IRON ORE MINING SECTOR

Canadian shipments of iron ore accounted for about 1.3% of global production. China and India are large but very high cost iron ore producers. Consequently, their production levels tend to fluctuate in tandem with ore prices, their domestic mines playing the role of price sensitive swing producers. Hence, substitution of domestic iron ore for imports occurs rapidly as soon as seaborne iron ore or pellet prices decline below certain levels. Canada is in direct competition with Australia and Brazil that dominate the seaborne market (Figure 1).

Canadian iron ore production is concentrated in the Labrador Trough and, in 2011, it was shared almost equally between Quebec (17 million tons) and Newfoundland and Labrador (16.5 million tons). There are presently four iron mines in production in Quebec (Table 2).

While the total value of iron ore exports increased from $CAN 143M in 2002 to $CAN 1048M in 2010, their destination shifted from Europe (85% in 2002) to China (69% in 2011). This substitution of the main export market carries a significant bearing on the competitiveness of Canadian mines relative to Australian, African and Brazilian producers which are closer to the Chinese and Indian markets (Table 3).

This geographical disadvantage is compounded by the fact that the iron content of Canadian ore is about half of that of mines in Australia and Brazil which requires the ore to undergo a concentration process prior to shipping (Figure 2).

Despite these constrains, two of the current mines in production are engaged in expansion programs to double production in 2012. Moreover, there are currently six new iron ore mine projects at different stages of development (Table 4). While these Quebec based projects have both higher capital intensity due to the greenfield nature of the projects and the new infrastructure required and higher cost structures due to lower grades and greater shipping distances, this is not stopping Asian steelmakers from acquiring interests in projects and companies to secure supply.

1.2 THE GOLD MINE SECTOR

Canada produced 110 tons of gold in 2011, about 4% of global production; Quebec produced approximately 28 tons. Hence, on a world basis, Quebec (and Canada) remains a relatively marginal producer, even though global production is much less concentrated than in the iron ore sector.

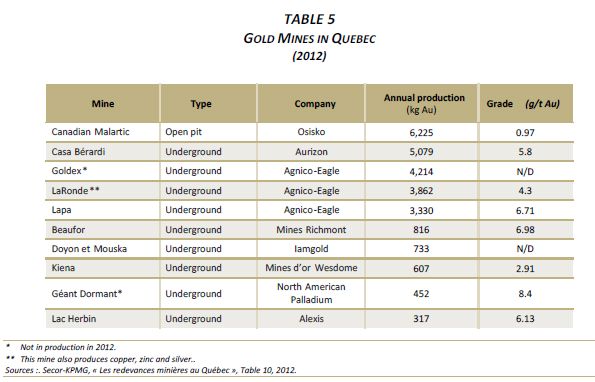

There are presently eight gold mines in production in Quebec, including one low grade high volume mine (i.e. Canadian Malartic) (Table 5). Development activities have been relatively buoyant in recent years. We count nine mining projects at various stages of development, including the world class Éléonore project with an estimated capital cost of $1.4 billion (Table 6).

2. MINING ROYALTY SCHEMES AND THEIR VARIANTS

The typology of mining royalty schemes put forward by the International Mining for Development Center comprises six categories of schemes:

- Royalties based on the volume of production

- Ad valorem royalties which are based on the value of production

- Royalties based on profits

- Royalties based on the economic rent of resources or 'super profits''

- Hybrid regimes with both an ad valorem and a tax on profit component

- Shared production contracts

In its comprehensive study of mining royalty schemes, the World Bank has retained four types of schemes for mining operations, discarding the scheme based on volume of production which is appropriate only for low value minerals (i.e. quarries) and shared production contracts which are mainly used in the petroleum industry6. The principal advantages and disadvantages of the different schemes are summarized in Table 7.

The conclusions of the analyzes concerning the impact of the major variants of mining royalty schemes can be enunciated as follows:

- The ad valorem royalty schemes facilitate the collection of royalties at a more constant level under various price variations. However, these schemes add a significant cost burden to the mining companies when the prices are low and the mining projects are less profitable since the payment of royalties is due even when profits are weak or inexistent. The effect is to accelerate the closure of mines when prices are depressed and threaten the continued viability of mining communities. Since these schemes add a significant amount of risks to the project, it reduces its estimated value relative to the same project subject to a royalty scheme based on profits and leads to the postponement or abandonment of several potential projects. This conclusion is particularly pertinent for Quebec where mines are characterized by relatively high production costs.

- Profit-based schemes adjust to variations in profitability over the life of the mine. Thus, when prices are low and mines become marginally or not profitable, this scheme does not compound the problem. This is particularly important in regions where production costs are higher. Avoiding a supplementary burden in such a situation can help mines pass through a depressed mining cycle without having to shut-down production, thus avoiding the painful socio-economic consequences that irremediably afflict local mining communities when such occurs. When prices are high and profits are up, a profit-based scheme gives governments a larger proportion of the value generated. However, the royalty amounts collected by the government will mirror the cyclability of the mining industry and there is a risk that they may be nil for some mines during certain years.

- The hybrid royalty schemes, including the 'Super Profit'' variant, combine the advantages and disadvantages of the other two categories. It is particularly important to monitor and adjust the royalty rates of the two components. Thus, if the ad valorem component is too high, the hybrid scheme will suffer the disadvantages associated with ad valorem scheme. It is also critical to determine the extent to which ad valorem royalties will be deductible from the profit-based royalties, as is the case in Australia and British-Columbia. In the absence of such a provision, the fiscal burden imposed on mining projects may well be too large, with the result that these projects will no longer be competitive and, therefore, may never be realized. Moreover, when prices adjust downwards or when the industry generally assumes that prices will decline, as are the current expectations, a hybrid royalty scheme takes on all the disadvantages of the ad valorem royalty scheme, disadvantages which are particularly significant for a jurisdiction characterized by relatively high costs of production.

It is generally observed that (i) ad valorem schemes are common in jurisdictions with weak tax administration organizations or low cost mining operations; (ii) profit-based schemes are preferred in jurisdictions with efficient tax collection agencies such as North American jurisdictions and, (iii) hybrid regimes are prevalent in jurisdictions which combine well developed fiscal authorities and abundant and low cost mining operations. This pattern is coherent with the above qualitative analysis. Notwithstanding the type of royalty scheme, the quantum of the royalty levies has considerable impact on the investment decision to develop a mine. This is accentuated by the fact that the selection of projects that will be financed is generally made on a competitive global scale. Table 8 summarized the main features of the mining royalty schemes and corporate tax levels in jurisdictions that are Quebec's main competitors in the iron ore and gold sectors.

Footnotes

1 The full report « Les redevances minières au Québec », July 2012 is available at : http://www.fmc-law.com/Home/Publications/0812_FMC_Co_authors_Mining_Royalty_Regime_Study.aspx?setlanguagecookie=1 . The analyses that underlie the Report were prepared by a team of SECOR-KPMG professionals led by Mr. Renault-François Lortie.

2 Financial support was provided to SECOR team by ArcelorMittal Mines Canada Inc., Osisko Mining Corporation, Goldcorp Inc., Iamgold Inc., Agnico-Eagle Mines Limited, Aurizon Mines Ltd, Quebec Mineral Exploration Association, Minalliance.

3 Excludes oil and gas.

4 Lac Otelnuk (iron ore), KeMag (iron ore), Éléonore (gold) and Renard (diamonds).

5 Fraser Institute Annual 'Survey of Mining Companies'', 2012.

6 Otto, J. et al. (2006). Mining Royalties : A Global Study on Their Impact on Investors, Government, and Civil Society. World Bank : Washington D.C..

To view this article in full together with its remaining footnotes please click here.

For more information, visit our Securities Mining Law blog at www.securitiesmininglaw.com

About Fraser Milner Casgrain LLP (FMC)

FMC is one of Canada's leading business and litigation law firms with more than 500 lawyers in six full-service offices located in the country's key business centres. We focus on providing outstanding service and value to our clients, and we strive to excel as a workplace of choice for our people. Regardless of where you choose to do business in Canada, our strong team of professionals possess knowledge and expertise on regional, national and cross-border matters. FMC's well-earned reputation for consistently delivering the highest quality legal services and counsel to our clients is complemented by an ongoing commitment to diversity and inclusion to broaden our insight and perspective on our clients' needs. Visit: www.fmc-law.com

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.