The pharmaceutical industry is divided into two categories of manufacturers: original drug companies and generics companies.

Original drug manufacturers are usually those who first look for new molecular targets that could be the target for completely new drugs and then, over the course of laborious and expensive research and development, create new preparations and formulations in order to verify the efficacy of the product in clinical trials, and finally register the new drug.

On the other hand, generics pharmaceutical manufacturers shorten the research and development process to include only a stage for developing alternative formulations or recreating the composition of original drugs based on the results of the research conducted by the original manufacturer.

However, today more and more generics companies are developing so-called improved generics, i.e. products that not only replicate known original drugs, but also offer added value in the form of, for example, improved bioavailability, reduced side effects or a more convenient form of administration.

Although the boundaries of the traditional division into original/branded medicines and generic medicines1 are becoming increasingly blurred, manufacturers of original medicines benefit from legal safeguards that compensate them for the research and development costs they incur.

Shortening the development path for generic products therefore comes at a price, as original companies benefit from additional protection regulated by pharmaceutical law. For pharmaceuticals authorised under the centralised procedure, this is known as the 8+2+1 formula, where the results of clinical trials are not made available for 8 years (data exclusivity), then there is a 2-year period where the company enjoys market exclusivity and finally, if they are able to register the drug for a new indication, an additional year of protection can be gained. Therefore, the development of generic alternatives to the original medicine is delayed.

In addition, manufacturers of original medicines benefit from patent protection for their products, thus enabling them to achieve a monopoly for 20 years in the market where the patent is in force.

The mechanism by which the exclusive use of a patented drug can be extended is called the Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC). SPC grants a right to extend patent protection for products that were the subject of the first marketing authorisation. Pursuant to EU regulations No. 469/2009 of 6 May 2009 and 1768/92, uniform regulations concerning SPCs were introduced, which allow an additional period of protection of a maximum of 5 years to be obtained for original products.

However, current changes taking place within the pharmaceutical market, in particular the strengthening market position of Asian companies, threaten to weaken the competitiveness of European manufacturers.

During the period of patent or SPC protection, but after the expiry of data protection, generics companies can only carry out the necessary research and development work that would have enabled them to develop their own generic medicine and carry out the registration process.

Under the current legal framework, a generics company can only start the production process of its medicine once the SPC expires. As we know, the production of medicines requires considerable preparatory work, including the purchasing of raw materials and optimisation and validation of the manufacturing process, which means that original companies in effect enjoy an additional monopolistic period of at least a few months before generic drug manufacturers can deliver their medicines to pharmacies.

In addition, the high costs of modern therapies often result in a significant reduction in their use and thus in their accessibility for patients. Because of these factors, the European Commission has begun to consider whether the current patent protection system in relation to SPCs should be modified.

Now, following an in-depth analysis of the market situation and the impact of regulation on this state of affairs, the European Commission has proposed a new "privilege" for generic drug manufacturers, the so-called SPC Manufacturing Waiver (SPC MW).2

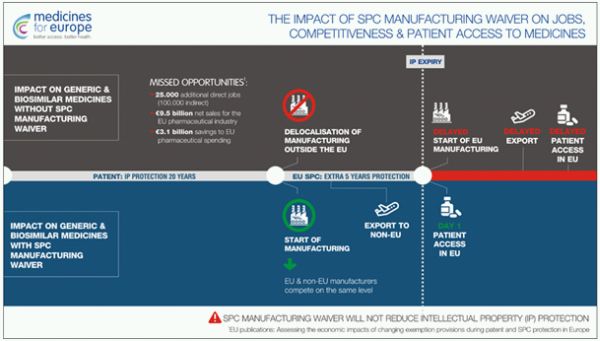

The aim of this regulation is to enable manufacturers to start production of generic medicines during the SPC period. However, these generic formulations can only be sold where SPC protection is not in place (for example, to non-EU countries). Such a "privilege" would allow generic medicines to be placed on the European market on the very first day after the expiry of SPC protection.3 The proposed relaxation of SPC protection is expected to improve the situation of generic companies and allow patients faster access to cheaper generic equivalents, thus giving them the opportunity to benefit earlier from the latest medicines.

The draft amendment4 to Regulation 469/2009 on SPCs sets out a list of derogations for the protection of medicinal products covered by the SPCs. This includes, inter alia, activities such as:

- the manufacturing of a protected SPC product or a medicinal product containing that product for the purpose of export to third countries;

- any related activities which are strictly necessary for manufacturing within the EU such products for export (for example, importing an active substance or excipients, manufacturing, packaging or temporary storage);

- manufacturing, no earlier than 6 months before the expiry of the SPC, a medicinal product covered by the SPC for storage until the expiry of the SPC to enable it to be sold after the expiry of the certificate; or

- carrying out, no earlier than 6 months before the expiry of the SPC, any related activities which are strictly necessary to manufacture the medicinal product for that purpose.

In addition to the benefits conferred by the SPC MW, a number of obligations for generics manufacturers have also been introduced in draft amendment 469/2009 for the sake of clarity and in order to eliminate possible abuses. Among other things, it is proposed that both the national medicine regulatory authority in the country where the SPC is in force and the SPC holder itself should be informed of the intention to manufacture the product during the SPC period no later than 3 months in advance, and that the product should be properly labelled as being for export5 in order to prevent repackaging or counterfeiting.

As outlined in a study commissioned by the European Commission and chaired by Charles River Associates,6 changes to the SPC regulation could bring enormous benefits to the European pharmaceutical market, such as:

- 9.5 trillion additional net sales

- 25,000 additional jobs

- 3.1 trillion euros of savings for the European health system.

Unfortunately, generics manufacturers and patients will have to wait for any changes resulting from the SPC MW "privilege" to take effect.

It is assumed that the SPC MW will not apply to medicines currently protected by the SPC, while for medicines for which an SPC has been applied before the approval of the amendments to the regulation and for which an SPC will be granted after the introduction of the SPC MW, the adopted time limit is 1 July 2022, or 3 years from the date of entry into force of the amended regulation.

The draft amendments to Regulation 469/2009 are currently pending approval by the European Parliament.

Footnotes

1. In this article the concept of generic medicines also covers biosimilar medicines.

2. http://www.spcwaiver.com/en.

3. ibid, infographic: "The Impact of the SPC Manufacturing Waiver on Jobs, Competitiveness & Patient Access to Medicines".

4. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-6638-2019-INIT/en/pdf.

5. Annex I of the draft amendment to Regulation 469/2009, draft logo to be affixed to products intended for export.

6. http://www.spcwaiver.com/en.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.