INTRODUCTION

Supplementary protection is key to the pharmaceutical industry and has now in general been made available more easily by the Court of Justice of the European Union ('the Court'). In November 2011 the court rendered judgments in two cases, and reasoned orders1 in three more, about the interpretation of Article 3(a) and (b) of the Regulation (EC) 469/2009 of 6 May 2009 concerning the supplementary protection certificate for medicinal products ('the SPC Regulation'). In December 2011, the court handed down an important decision that related to supplementary protection certificate ('SPCs') and paediatric extensions. And just recently, the court published its orders of 9 February 2012 regarding the scope of protection of SPCs. For easy reference, the court's late 2011 and early 2012 case law regarding SPCs is summarised in Table 1. Even though the overall effect of the decisions for the innovative pharmaceutical industry is positive, not all issues regarding SPCs have been resolved.

In this article we first discuss what SPCs are. Subsequently we highlight the main points of the decisions of November 2011. This SPC case law concerns the interpretation of Article 3(a) and (b) of the SPC Regulation, that is, two of the conditions for obtaining SPCs. The December 2011 Merck case2 concerns the duration of an SPC (Article13 SPC Regulation) and is dealt with next. The following section addresses the scope of protection of SPCs as decided in the Novartis cases. Although the rules for granting SPCs are now considerably clearer, several issues remain unresolved. These issues as well as the practical implications of the late 2011 and early 2012 SPC case law are dealt with in the discussion. A short conclusion can be found at the end of the article.

BACKGROUND: SPCs AND THE SPC REGULATION

SPCs are sui generis industrial property rights intended to compensate pharmaceutical companies for the loss of effective patent term caused by the delay in obtaining regulatory approval for medicinal products,4 that is for (performing clinical studies and) obtaining a marketing authorisation ('MA') for the product, as laid down in Directive 2001/83/EC or Directive 2001/82/EC (for human or veterinary use, respectively).

There is a similar regulation in place for the extension of patents for plant protection products that have been granted a marketing authorisation,5 to promote research and innovation for plant protection ('the Plant SPC Regulation'). The Plant SPC Regulation will not be discussed separately here. However, as both regulations are similar in the sense that the conditions to obtain an SPC are virtually identical: most of what is discussed below6 is likely to be relevant to SPCs for plant protection products as well.

SPCs are highly valuable as they extend the period during which a drug can be marketed exclusively to the benefit of the originator pharmaceutical company. An SPC can extend the term of exclusivity of a patent for up to five years. Such patent extensions are regulated by way of EC regulations with a view to harmonising SPC law throughout the Community. However, as SPCs are applied for nationally with the competent national Industrial Property Office ('the IPO'), the SPC Regulation has been interpreted differently in various countries, leading to disharmony, notably to granting or not granting SPCs, different durations and different scopes of exclusive rights attributed to SPCs throughout Europe. Both German and UK courts posed questions to the court regarding the interpretation of the SPC Regulation. Six of these referrals resulted in final rulings in late 2011. Two resulted in rulings in early 2012. Rulings of the court are binding on all EC national courts and IPOs.

OBTAINING AN SPC: CONDITIONS AND DURATION

In the first part of this section, the conditions for obtaining an SPC is discussed and in the second part we address a specific issue regarding the duration of SPCs, namely whether a negative term SPC is possible and why this is relevant.

Conditions for Obtaining an SPC: the Court's Interpretation of Article 3(a) and (b)

As set out in Article 3 SPC Regulation, an SPC shall be granted (by the IPO of the Member State in which the application is submitted) if, at the date of the application:

- the product is protected by a basic patent in force;

- a valid MA to place the product on the market as a medical product has been granted in accordance with Directive 2001/83/EC or Directive 2001/82/EC7 as appropriate;

- the product has not already been the subject of an SPC; and

- the MA referred to in (b) is the first authorisation to place the product on the market as a medicinal product.

These requirements all gave rise to different interpretations and were (or still are) the subject of referrals to the court. The late 2011 cases concerning conditions (a) and (b) will be discussed below.

To illustrate the issues regarding the application of requirements 3(a) and (b), we will first look at the different interpretations given in pre-Medeva and Georgetown Europe. We then discuss the new situation regarding combination products clarified by the court in the Medeva and Georgetown judgments and the Daiichi and Yeda orders. An additional teaching regarding product-by-process claims of the Queensland order is addressed and we will also discuss the one-patent-one-SPC-confusion.

Pre-Medeva and Georgetown: disharmony in Europe

Disharmony regarding the interpretation of the requirement 'the product is protected by a basic patent in force' of Article 3(a) SPC Regulation existed in Europe, especially with regard to combination products. The SPC Regulation defines a 'product' as the active ingredient or combination of active ingredients of a medicinal product (Article 1(b) SPC Regulation). If the (combination) product is fully disclosed in the claims of a patent, and if the MA is granted for the same (combination) product, no issue arises. However, a mismatch may occur between the 'product' that is patented and the 'product' for which an MA is granted. When an MA is granted for a combination of active ingredients, as is frequently the case with multi-disease vaccines where public health policy requires such combined marketing, the combination of active ingredients is 'the product placed on the market as a medicinal product' of Article 3(b). However, in those cases the patent usually covers only one active ingredient (or a combination of two) and does not 'disclose' the full combination in the claims of the patent. It was generally assumed that the concept 'the product' of Article 3(a) needed to match 'the MA product' of Article 3(b). The question arose whether in these circumstances the product of Article 3(b) that has been placed on the market is 'protected by a basic patent in force' as required by Article 3(a). Can an SPC be granted in case the basic patent relates to active ingredient A and the MA was granted for the combination of active ingredients A + B?

The focus in these types of cases was not on the interpretation of the term 'product' of Article 3(a) and 3(b) of the SPC Regulation but rather on the interpretation of the requirement 'protected by a basic patent' of Article 3(a). The court previously held in Farmitalia8 that the question whether a product is protected by a basic patent according to Article 3(a) of the SPC Regulation must be answered based on the national rules governing that patent, in the absence of Community harmonisation of patent law. Different theories developed across Europe regarding the interpretation of 'protected by a basic patent', that can be divided into two main 'tests'. The controversy was whether the wording of the basic patent ('the disclosure test'9) or the patent's scope of protection ('the infringement test') should be decisive in determining whether the product (for which the MA was given) is 'protected' by a basic patent according to Article 3(a). This lack of clarity resulted in conflicting interpretations by national IPOs and courts throughout Europe. In the Netherlands, France, Germany and the United Kingdom the 'disclosure doctrine'10 was applied, whereas authorities in, for instance, Switzerland, Belgium and Italy applied the infringement test. The latter was more advantageous for the originator pharmaceutical company (in the pre-Medeva era).

Illustrative of the disharmony in Europe is Novartis's experience regarding the granting of SPCs for its product valsartan: the uncertainty led to different SPCs and many court cases, with contradictory results across Europe. Novartis owned a European patent EP 0443983 (which expired on 12 February 2011) claiming the active pharmaceutical ingredient valsartan, processes for the production of valsartan as well as first and second medical uses of valsartan. It also has an MA for valsartan and another MA for the combination product valsartan/HCTZ (Hydrochlorothiazide) for the treatment of hypertension. In most European countries, Novartis applied for two SPCs (one for the product valsartan and one for the combination product) and for a paediatric extension. The different SPCs granted can be seen in Table 2 below. In most countries Novartis could only obtain an SPC for its product valsartan and not for its other product valsartan in combination with HCTZ (except for Belgium and Italy).

The table below would imply that many countries already interpreted the SPC Regulation as the court would later do in Medeva and Georgetown but this is not the case. In several countries, Novartis had two MAs and since one of them (valsartan) did not suffer from a mismatch between the 'patent'-product and the 'MA'-product, Novartis could obtain an SPC for valsartan, also in countries where the 'disclosure test' was applied.

The court has now addressed the issues regarding the interpretation of Article 3(a) and (b) for combination products in Medeva and Georgetown and in the three subsequent reasoned orders (Yeda, Queensland and Daiichi) as is explained below.

Medeva (C–322/10) and Georgetown (C–422/10): if the basic patent claims A and the MA is for A+B, an SPC can be granted for A

Medeva owned a patent relating to two antigens of the whooping cough. However, the vaccines marketed (and hence the MAs) contained additional active ingredients, directed at diphtheria, tetanus, meningitis and/or polio. Medeva applied for five SPCs with the UK IPO, four covering combination vaccines and one limited to the two patented components only. The IPO rejected all SPCs, the first four for not complying with Article 3(a) of the SPC Regulation, because the product containing multiple active ingredients of the MA relied on was not considered to be protected by the basic patent. The SPC directed at only the two patented components was rejected for non-compliance with Article 3(b), as there was no valid MA in place because the MA contained more active ingredients than the product claimed in the patent. The Court of Appeal (England and Wales) referred the case to the court in June 2010 where it was registered as C–322/10. On 24 November 2011, the court handed down its decision in this case. It ruled firstly, regarding Article 3(a) that:

Article 3(a) of Regulation (EC) No 469/2009 ... must be interpreted as precluding the competent industrial property office of a Member State from granting a supplementary protection certificate relating to active ingredients which are not specified in the wording of the claims of the basic patent relied on in support of the application for such a certificate. (emphasis added)

In other words, an SPC can only be obtained for the active ingredients that are specified in the wording of the claims of the patent. It is noteworthy that in its three reasoned orders, Yeda, Queensland and Daiichi (to be discussed below), the court replaced 'specified' by 'identified' (in the original English language orders, not in translated versions13) without giving any explanation for this change. The possible significance of this is a subject of discussion.

Secondly, with regard to Article 3(b) of the SPC Regulation, the court ruled that:

Article 3(b) of Regulation No 469/2009 must be interpreted as meaning that, provided the other requirements laid down in Article 3 are also met, that provision does not preclude the competent industrial property office of a Member State from granting a supplementary protection certificate for a combination of two active ingredients, corresponding to that specified in the wording of the claims of the basic patent relied on, where the medicinal product for which the marketing authorisation is submitted in support of the application for a special protection certificate contains not only that combination of the two active ingredients but also other active ingredients. (emphasis added)

This can be interpreted as follows. If the basic patent specifies/identifies active ingredient A only, and the MA was granted for a combination of active ingredients A + B, an SPC can be granted for A. This is also apparent from paragraphs 31 and 38 of the Georgetown and Medeva decisions respectively, making reference to paragraphs 34 and 39 of the Explanatory Memorandum.14 Georgetown also concerned a multi-disease vaccine but only Article 3(b) was at issue and the patent concerned only one active ingredient; the court's ruling in that case is identical to the second part of Medeva and will not be discussed separately.

The interpretation endorsed by the court is a combination of a teleological interpretation of Article 3(b) combined with a rather strict interpretation of Article 3(a). We will refer to this as 'the Medeva test'. Regarding the interpretation of 3(a), it seems closer to the 'disclosure test' than to the 'infringement test', but it should be noted that the 'disclosure test' in itself was the subject of different interpretations throughout Europe and even within countries; such was the case in the United Kingdom where the referrals originated from. The court seems to have applied a strict interpretation of the 'disclosure test'. Some challenges regarding the applicability of the Medeva test are addressed in the discussion.

Daiichi (C–6/11) and Yeda (C–518/10): further clarifications regarding combination products

On 25 November 2011, the day after the Medeva and Georgetown rulings, the court handed down three reasoned orders in other SPC cases concerning combination products. The rulings are mostly repetitions of the aforementioned cases, but provide some additional insights which are highlighted below.

Daiichi owns a patent regarding an active ingredient A. It obtained an SPC for this product based on an MA containing A as the sole active ingredient. Daiichi invested considerable time and resources in undertaking further clinical trials and studies for a combination therapy of A+B. The clinical trials were successful and Daiichi then sought an SPC relying on the MA it had obtained for the combination product and on the same basic patent. The British IPO refused this second SPC for the combination therapy on the grounds that the active ingredients of the MA are not protected (that is, disclosed) by the basic patent within the meaning of Article 3(a). After another UK referral, the court in confirming the IPO's decision in Daiichi used the exact wording of Medeva, making clear that the Medeva test is not limited to multi-disease vaccines but applies to all combination products.15

Yeda involved another reasoned order. Yeda owns a European patent that discloses a therapeutic composition A+B. The patent also claims the administration of both components separately, provided they are part of the same composition. Yeda applied for two SPCs, one for the composition A+B and one for active ingredient A only. The supporting MA only covered product A, but indicated that it should be administered together with B. Certain national IPOs granted SPCs to Yeda but the British IPO refused both SPCs. Yeda appealed only the refusal of the SPC for A stating that since A would indirectly infringe on the patent for A+B, the patent would protect A and thus an SPC for A should have been granted now that the MA was for A as well. Following a referral by the Court of Appeal, the court clarified that an SPC cannot be granted for A:

... where the active ingredient specified in the (marketing) application, even though identified in the wording of the claims of the basic patent as an active ingredient forming part of a combination in conjunction with another active ingredient, is not the subject of any claim relating to that active ingredient alone. (emphasis added)

Thus an SPC cannot be granted for A if the patent claims A + B in combination only and the MA relied on for the application applies to just A.

Queensland (C–630/10): product-by-process claims and SPCs The third reasoned order rendered on 25 November 2011 concerned Queensland, the owner of a parent patent and two divisional patents. The parent patent claims several active ingredients (by product-through-process claims) and the divisional patents claim additional active ingredients.

The two MAs relied on for the SPC applications contain a combination of active ingredients both from the divisional patents and from the parent patent. The actual court ruling regarding most questions referred is no surprise and is a literal copy of the rulings in Medeva. However, a new question was whether, in a case involving a basic patent relating to a product-by-process claim, it is necessary for the 'product' to be obtained directly by means of that process. The court ruled that it is irrelevant whether the product is derived directly from the process, but that Article 3(a) SPC Regulation:

precludes [an SPC] being granted for a product other than that identified in the wording of the claims of that patent as the product deriving from the process in question.

In other words, if the (in)direct product is not specified/ identified in the wording of the claims, an SPC will not be possible for that active ingredient.

Only one SPC for a basic patent?

A consideration, though not part of the actual rulings, in Medeva,16 Georgetown17 and Queensland18 that sparked discussion is:

where a product is protected by a number of basic patents in force, each of those patents may be designated for the purpose of the procedure for the grant of a certificate but only one certificate may be granted for that basic patent ... .19

A similar consideration was given in Biogen/SKB20 in 1997. It seems to imply that one MA concerning a combination of active ingredients can be relied on for several SPC applications, provided the constitutive active ingredients are specified in the wordings of the claims of different basic patents and provided the other requirements of Article 3 are also met. However, the wording of the consideration was also understood to limit the number of SPCs granted for a basic patent to one. If this understanding is correct, this would be contrary to current practice, where several SPCs can be and are granted by national IPOs based on different active ingredients specified in one basic patent. Biogen/SKB was widely interpreted to mean 'one SPC per product per patent'. This is also in line with Article 3(2) Plant SPC Regulation.21 We therefore expect that the recent decisions will not affect the existing practice; it should remain possible to obtain more than one SPC relying on the same basic patent if the patent claims several active ingredients independently (that is, not as part of a combination). Indeed, Arnold J, in Queensland22 allowed two SPCs based on the same basic patent, for different active ingredients, with reference to the UK IPO's interpretation.

The Merck Case: SPC with Negative Term? – Article 13 SPC Regulation

In Merck (C–125/10) the court was asked to clarify Article 13 SPC Regulation. More specifically, it was asked to rule whether an SPC can have a negative term. We first explain what a negative term SPC is and why a company would be interested in obtaining one; we subsequently point out how this gave rise to different interpretations in Europe; and we round off this section with the decision of the court regarding negative term SPCs.

Background to Article 13

Article 13(1) and (2) SPC Regulation stipulate that an SPC takes effect at the end of the lawful term of the basic patent and that its duration may not exceed five years from the date on which it takes effect. The calculation of the duration of the SPC can be summarised as follows:

SPC term = (X–Y) – 5 years

X = date of first MA in the Community

Y = application date of basic patent.

For instance, if the patent was applied for on 1 July 1999 and the first MA in the EU was granted seven years later on 1 July 2006, the SPC duration will be two years. In cases where the MA is granted within five years of the application date of the patent, this would result in an SPC with a negative term. When the predecessor of the present SPC Regulation was introduced in 1992,23 a negative term SPC was not beneficial for the rights holder and consequently not applied for. This changed in 2006 with the introduction of the 'Paediatric Regulation',24 which provided for a six-month extension for an SPC already in place for a medicinal product, in order to promote research regarding the effects of the medical product at issue on the paediatric population. After the introduction of the Paediatric Regulation, the maximum term of patent-related exclusivity for a medicinal product is 15.5 years (patent + SPC + paediatric extension).

As the granting of a 'paediatric extension' is possible only if an SPC is in place, a six-month extension of a negative term SPC, provided the negative term is less than six months, can result in considerable benefits for the proprietor. Drugs are usually at their most profitable stage at the end of the patent term and every day of extended exclusivity can give considerable profits. However, not all national IPOs agreed on how to handle cases in which the MA was granted within five years of the application date for the patent.

Disharmony in Europe: different term or no SPC(s) granted for sitagliptin (Merck)

Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. ('Merck') applied for an SPC throughout Europe for its product sitagliptin, a DPP inhibitor used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. The MA on which Merck based its application was obtained less than five years after the application date of the basic patent. The resulting SPC term would be minus three months and 14 days. Merck's application resulted in various decisions, including:

- the grant of a negative term SPC by the IPOs in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands;

- the grant of a zero term SPC in Greece (because it was believed a negative term was not possible and should be rounded up to zero); and

- no SPC in Germany as the IPO argued that a negative term SPC was not possible.

Merck appealed the German decision before the Bundespatentgericht, which referred the question of a negative term SPC to the court, in light of the possibility of obtaining a paediatric extension which would result in a positive term extended protection. This resulted in Case C–125/10.

Judgment of the court in Merck (C–125/10) (sitagliptin)

On 8 December 2011, the court ruled on those questions that it is possible to obtain a negative term SPC in view of the Paediatric Regulation. It also ruled that a paediatric extension should commence on the date determined in accordance with the (negative) term calculated according to Article 13(1) of the SPC Regulation (in other words, in this case prior to patent expiry). The court also explained that a negative term SPC cannot be rounded up to zero and that

... it is only in the case where the period between lodging the basic patent application and the date of the first MA in the EU for the medicinal product in question is exactly five years that an SPC can have a duration equal to zero and that the starting point of the paediatric extension of six months is concurrent with the expiry date of the basic patent.25

In this case the SPC had a protection period of minus three months and 14 days, hence with a six-month paediatric extension, Merck could benefit from additional exclusivity during the two months and 16 days following the expiry of the patent.

SUBJECT-MATTER OF PROTECTION AND EFFECTS OF SPCs: ARTICLES 4 AND 5 SPC REGULATION

Now that we have discussed cases concerning the obtaining of an SPC it is worth considering what it is that one actually obtains. SPCs are sui generis intellectual property rights that can extend the period of 'protection' of a pharmaceutical product for five years (at the end of the patent term, which is generally the most beneficial period for pharmaceuticals). The question is what the protection of an SPC actually consists of, and once again attempts at an answer caused disharmony in Europe. Recently this question was dealt with by the court in referrals from the United Kingdom and Germany in cases between Novartis and Actavis concerning valsartan (the UK C–442/11 and German C–574/11 cases).

Background to Articles 4 and 5

The subject-matter and effects of protection of SPCs is dealt with by Articles 4 and 5 SPC Regulation. These Articles may be seen as contradicting each other and they gave rise to different interpretations, resulting in a difference in the scope of protection afforded to SPCs in different European countries. Articles 4 and 5 of the SPC Regulation read:

Article 4 Subject matter of protection

Within the limits of the protection conferred by the basic patent, the protection conferred by a certificate shall extend only to the product covered by the authorisation to place the corresponding medicinal product on the market and for any use of the product as a medicinal product that has been authorised before the expiry of the certificate.

Article 5 Effects of the certificate

Subject to the provisions of Article 4, the certificate shall confer the same rights as conferred by the basic patent and shall be subject to the same limitations and the same obligations. (emphasis added)

Article 4 limits the protection to the product covered by the MA, whereas Article 5 confers on the SPC the same rights as the basic patent. The question has arisen whether, for instance, an SPC for A can be enforced against a medicinal product that contains not only active ingredient A but also active ingredient B. If the original product on the market contained only A, it would seem that according to Article 4 the protection cannot extend beyond a product containing only active ingredient A.

The background of these two Articles is rather different, and originates from the fact that the SPC is a sui generis right that lies at the interface between the system governing MAs for medical products on the one hand and patent law on the other hand. SPCs are meant to provide supplementary protection to a patented product. Article 5 aligns with the rights conferred by the basic patent. However, the rationale of the SPC Regulation is to compensate for lost time in (performing clinical studies and) applying for an MA for a specific product. In that respect, Article 4 could be understood to align the scope of protection of an SPC to the actual product authorised (for which the actual delay has occurred).

Disharmony in Europe

As an example of the disharmony regarding the interpretation of Articles 4 and 5, we will again look at the valsartan situation in several European countries. As already mentioned, Novartis owned a European patent claiming the active ingredient valsartan ('A'), which expired on 12 February 2011. In several countries Novartis has two MAs for products that contain valsartan as an active ingredient: (i) an MA for a product containing valsartan ('A') only, and (ii) an MA for a product containing valsartan in combination with HCTZ ('A+B'). Novartis – in the pre-Medeva era – obtained SPCs in various European countries for A and/or A+B (see Table 2). In most countries, however, Novartis had an SPC for A only.

In late 2010, several generic companies indicated their intention to market a generic medicinal product containing A+B after expiry of the patent. In several proceedings that followed, the issue arose as to whether an SPC for A would confer protection against a pharmaceutical product containing A and B. The answer varied by country, by court and in some cases even by judicial chamber.

In Norway, the court held on 10 February 2011 that Actavis's generic A+B infringed Novartis's SPC for A. In Belgium, the situation was different, as Novartis had SPCs for both A and A+B. In a declaratory action started by Teva, Teva sought to (i) invalidate Novartis's SPC for A+B, and (ii) obtain a declaration of non-infringement of Novartis's SPC for A by Teva's generic A+B. On 13 May 2011 the Antwerp Court held that Teva's generic A+B did not infringe Novartis's SPC for A because the scope was limited, but at the same time held that it did infringe Novartis's valid SPC for A+B. The Antwerp Court made reference to the Explanatory Memorandum:26

20. The proposed system takes the legal form of a new protection certificate, sui generis, which is national in character and lies at the interface between two systems, that of prior authorizations for the placing on the market of medicinal products and that of their protection by patent, and which confers on the system its specific characteristics and special nature. These can be seen first of all in the scope of the certificate and the conditions for obtaining it ... They can also be seen in the subject of protection. [This last sentence is not cited by the Antwerp Court]

38. [The SPC is] a protection certificate sui generis inasmuch as it is linked to both an authorization to place the product on the market ... and to a previous patent (the basic patent).

The Antwerp Court also made reference to preamble 10 to the SPC Regulation:

... the protection granted should be strictly confined to the product which obtained authorisation to be placed on the market as a medicinal product.

It furthermore considered it relevant that Novartis had in fact accepted the limited protection of its SPC for A by applying for a separate SPC for A+B.

In France, conflicting decisions have been handed down in cases concerning the scope of protection of an SPC. In Novartis v Sanofi, the Paris Court of First Instance held27 that Sanofi's combination generic A+B infringes Novartis's SPC for A. An injunction was granted prohibiting the manufacture, importation, offer for sale, holding, storing and marketing of the generics as well as ordering the recall of the products from every distribution channel. This contradicts earlier French case law in two ways. Firstly, in the Losartan cases, the injunction granted was more limited, as both the President of the Paris Court of First Instance and the Court of Appeal had only prohibited the sale of generics until the expiration of the SPC, but had refused to prohibit the importation, detention or manufacture of the generics:

It is not appropriate to grant the respondents' claim for prohibition of the manufacture, holding, use or importation of these products before this date because the products at stake are generic products that have been granted the necessary authorisations from the public authorities, and which must be marketable as soon as the protection granted by the patent and SPC held by the respondents lapses. Only the marketing before the end of the protection period can be enjoined.28

Secondly, Novartis v Sanofi contradicts a judgment regarding valsartan of the Paris Court of Appeal of 16 September 2011 where the combination product valsartan and HCTZ was held not to infringe Novartis's SPC for valsartan.29 The Court of Appeal:

Considering that the product as defined by the regulation is not restricted to an active ingredient and that the SPC pursuant to Article 4 does not protect the active ingredient but rather the product so that the SPC protects the valsartan product only.

Questions from the United Kingdom and Germany regarding the interpretation of Articles 4 and 5 SPC Regulation were referred to the court.

Judgment of the Court in Novartis (C–442/11 and C–574/11)

The court ruled on those questions that:

Articles 4 and 5 of (the SPC) Regulation ... must be interpreted as meaning that, where a 'product' consisting of an active ingredient was protected by a basic patent and the holder of that patent was able to rely on the protection conferred by that patent for that 'product' in order to oppose the marketing of a medicinal product containing that active ingredient in combination with one or more other active ingredients, a supplementary protection certificate granted for that 'product' enables its holder, after the basic patent has expired, to oppose the marketing by a third party of a medicinal product containing that product for a use of the 'product', as a medicinal product, which was authorised before that certificate expired.30

In other words, if Novartis was able to invoke its patent for A against an authorised medicinal product containing A and other active ingredients, it could also invoke its SPC for A against such product. Whether this is the case is, of course, left to national courts to decide on the basis of national law. The court did note in the order on the UK referral:

In the case before the national court, it is common ground that the marketing of a medicinal product containing valsartan in combination with hydrochlorothiazide for use in the treatment of high blood pressure would infringe the rights conferred by the patent for valsartan.31

DISCUSSION

In this section we first address several issues that still remain insufficiently clear after the late 2011 and early 2012 decisions, with reference to some examples of the court's recent case law applied by national courts. Subsequently we look at the possible consequences of the decisions for SPCs that in retrospect should not have been granted. Lastly we discuss some issues with respect to the protection and effect of SPCs.

Obtaining an SPC: Questions Remain

Challenges regarding the application of the Medeva test As pointed out above, the Medeva test seems closer to the 'disclosure test'32 than to the 'infringement test'. However, how practical are the guidelines provided by the court? It remains unclear what exact 'identification' or 'specification' in the wording of the claims of the patent is required by the Medeva test. The choice of a different verb ('specified' in Medeva and Georgetown and 'identified' in Yeda, Queensland and Daiichi), although not present in translations, might be relevant. Is one more precise or narrower than the other? It is to be expected that the question of whether an active ingredient is specified or identified in the wording of the claims of the basic patent will lead to discussion and possibly more referrals to the court. Is it always possible to identify the product of a process claim sufficiently for this test? When are complicated biologics specified or identified sufficiently? Is it sufficiently specific to define a product in functional terms? For example, is an antibody sufficiently specified/identified by claiming that it is specific to a certain antigen without disclosing the exact structure of the antibody itself? What if the patent claims a whole list of products defined by the same functional terms? The drafting practice for patents will presumably be reconsidered as a consequence of the Medeva test.

Since the court's decisions, several cases were decided by national courts in which this issue came up. In Lundbeck v Tiefenbacher and Centrafarm33 the Court of Appeal of The Hague found that the salt escilatopramoxalate, although not named in the wording of the process claim, was sufficiently specified/identified. The court first nullified all product claims of the patent. The remaining process claim concerned a method for the preparation of escitalopram (an S-enantiomere of citalopram) and non-toxic acid-addition salts thereof. With reference to Queensland and the Medeva test, the court then determined whether the SPC granted for 'Escilatopram, if so desired as a pharmaceutically acceptable acid-addition-salt thereof, especially escitalopramoxalate'34 (based on an MA for the same active ingredient) was valid. The Court of Appeal determined that the remaining claim of the patent specifically claims non-toxic acid-addition salts of escilatopram. The salt covered by the SPC and the MA (escilatopram oxalate) is not mentioned literally in the claim, but is mentioned as a specific example-product of the process in the description. The Court of Appeal was then left with the question whether this would be considered to be sufficiently specified/identified in the wording of the claims. The Court of Appeal referred to the latest decisions and orders by the court in this respect (Medeva and so on) and considered the following on whether identified would be different from specified:

It seems plausible that the terms 'identified' and 'specified' have the same meaning in the absence of a clear explanation thereto.35

The Court of Appeal then concluded that the SPC was indeed valid as the product was sufficiently identified in the wording of the claims.36

The UK High Court also decided on this issue post-Medeva in Novartis v Medimmune.37

It is noteworthy that in Arnold J's first judgment in this case38, he held that (i) the patent was invalid, and (ii) claim 1 did not cover the process by which ranibizumab is produced (and could thus not be infringed by a product containing ranibizumab). As a result, the SPC for ranibizumab would be invalid. But, because Arnold J gave permission to appeal, under UK law he needed to address all issues in these proceedings on the hypothesis that the patent would be held valid and infringed in appeal, which resulted in his second judgment discussed here.

The relevant claim of the basic patent was also a process claim identifying the product of the method functionally as 'a molecule with binding specificity for a particular target'. The SPC and MA concerned the product ranibizumab, which was indeed a possible product of the process claimed. But there was debate on whether ranibizumab would be actually specified/identified in the wording of the claims as the product deriving from the process in question. Novartis argued that claim 1 did not identify ranibizumab because this would not have been developed until several years after the patent was applied for. Arnold J held that ranibizumab was not specified/identified in the wording of the claims (and it was held not to be identified in the description either) as the product deriving from the process in question and on that basis invalidated the SPC. In so doing, Arnold J made reference to the recent decisions of the court, including the Medeva test. Arnold J held that he found the test provided by the court was not sufficiently clear, apart from its rejection of the infringement test. He expected that at some stage this would lead to more referrals. In this case no questions were referred and Arnold J put forward some interesting considerations:

Secondly, the Court's rulings do not merely require the product to be specified in the claims (compare section 125(1) of the 1977 Act), but specified or identified in the wording of the claims. It appears to me that this points to a test which is more demanding than merely requiring that the product be within the scope of the claim, although it is not clear how much more demanding.

Thirdly, even if Medeva can be interpreted as leaving open the possibility that it is sufficient for the product to be within the scope of the claim where the claim is a product claim, it seems to me that Queensland lays down a narrower rule in the case of process claims. The Court of Justice requires the product to be identified in the wording of the claim as the product deriving from the process in question. Furthermore, it says that it is irrelevant whether or not it was possible to obtain the product directly by means of that product, which points away from an infringement-type test. In the present case, claim 1 merely identifies the product of the method as 'a molecule with binding specificity for a particular target'. This covers millions of different molecules of various kinds. It is not even limited to antibodies. Although ranibizumab falls within this extremely broad class of products, there is nothing at all in the wording of the claim, or even the lengthy specification of the Patent, to identify ranibizumab as the product of the process in question.39 (emphasis added)

The High Court of Justice also decided in Queensland v Comptroller General40 after referral. In this case the interpretation of the court's instructions was straightforward. Queensland's appeal concerned two groups of SPC applications. The first group defined the product as the combination of antigens (that is, active ingredients) as covered by the relevant MA; the second group of applications defined the product as a single antigen mentioned in the basic patent and selected from the combination covered by the MA. On 14 February 2012, Arnold J dismissed the appeal relating to the first group of SPC applications as the appellants (Queensland), after the court's ruling, accepted that they did not comply with Article 3(a) SPC Regulation since the combinations claimed included active ingredients which were not identified in the wording of the claims of the basic patents. Arnold J allowed the appeal for the second group of SPCs in view of the court's interpretation of Article 3(b), as accepted by the Comptroller General.

Consequences for SPCs granted prior to these decisions that should not have been granted

The court's decisions regarding negative SPCs and Article 3(a) and 3(b) may have consequences for SPCs that in hindsight should not have been granted. This is, for instance, the case in countries where the infringement test was used for the interpretation of Article 3(a), namely where SPCs for A + B were granted even if the basic patent protected only A. Article 15 SPC Regulation stipulates that the certificate will be invalid if it was granted contrary to the provisions of Article 3. Indeed, following the court's decision in Medeva, this has already led to the Court of Rome ruling on 25 November 2011 that Novartis cannot invoke its (Italian) SPC granted for the combination product valsartan and HCTZ, as only valsartan is specified in the wording of the basic patent (Table 2), clearing the way for Mylan and others to market their generic combination product in Italy (there was no Italian SPC for A).

In cases where the term of SPCs (and paediatric extensions) is incorrect after the Merck decision, for example in countries where negative SPCs were rounded up to zero, the SPCs can also be challenged. However, the SPC Regulation is less clear about the consequences for violation of Article 13. It is to be expected that the SPC will not be revoked but that its duration will be amended.

Scope of Protection

Post-Medeva an SPC can now be obtained for A if the patent protects A and the MA has been obtained for A+B. In Novartis, questions on the scope of protection and effects were dealt with; an SPC for A confers the same rights as a patent for A (and thus the SPC for A could be enforced against a product containing A+B). It has been suggested (and in fact the decision itself seems to suggest) that this means that SPCs confer the same rights and have the same scope of protection as the basic patent. However, Novartis's SPC for A in the United Kingdom was granted on the basis of an MA for A (pre-Medeva). Thus this case did not relate to an SPC granted post-Medeva applying the Medeva test. Because the MA was for A and the SPC as well, the crucial part of Article 4 was no drawback to the Court's decision:

... the protection conferred by a certificate shall extend only to the product covered by the authorisation to place the corresponding medicinal product on the market. (emphasis added)

This part of Article 4 has even more relevance in view of consideration 20 of the Explanatory Memorandum regarding the interface between the patent system and the rules governing the MA:

They [that is, the interface] can also be seen in the subject of the protection, which is limited both by the authorisation itself since the protection extends only to the authorised product and only for the therapeutic uses of it which were the subject of an authorisation, and in the claims for the basic patent. (emphasis added)

It therefore remains to be seen whether the outcome would be different if an SPC was obtained for A, the MA is for A+B and the patent for A (applying Medeva). What if (the majority of) the delay (in obtaining an MA) was caused by performing clinical trials on A+B or B and/or meeting the requirements of the regulatory authorities directed at A+B (and thus not on A as such)? Could such an SPC for A be enforced against a product containing A+C or even against a product containing only A (let alone for which therapeutic uses)? If not, would this then prove to be of relevance to the SPCs granted post-Medeva?

CONCLUSION

In the past year issues regarding Articles 3, 4, 5 and 13 SPC Regulation have been resolved. The court's interpretation of Article 3(a) and (b) has clarified the granting of SPCs in particular for combination products, to a certain extent.

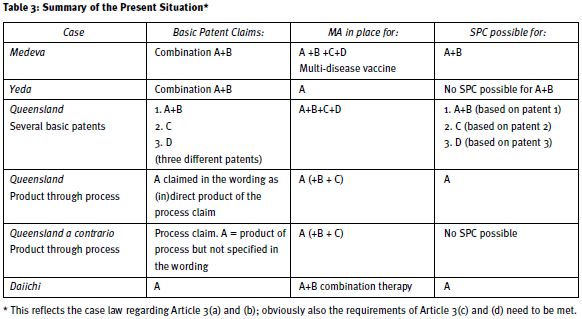

For easy reference we include a table summarising the situation for granting SPCs for combination products after the 2011 court decisions regarding Article 3(a) and (b) SPC Regulation (Table 3), obviously on the condition that A, B and so on are (sufficiently) specified/identified in the wording of the claims of the basic patent.

However, issues remain. Regarding Article 3(a) the court ruled that an SPC cannot be granted for 'active ingredients which are not specified/identified in the wording of the claims of the basic patent'.

It is unfortunate that this guideline provided by the court is rather unclear, leaving room for different interpretations and is likely to lead to more referrals to the court. Arnold J mentioned in MedImmune v Novartis that he found the test provided by the court not sufficiently clear, apart from its rejection of the infringement test, adding: 'Regrettably, therefore, it is inevitable that there will have to be further references to the (Court) to obtain clarification of the test.'

Furthermore, the rulings are likely to have consequences for drafting practice.

The court has also clarified Article 13 SPC Regulation, ruling that negative SPCs are possible in view of the Paediatric Regulation.

Lastly, the court clarified that a medicinal product for a combination of active ingredients A + B infringes an SPC for an active ingredient A. In other words, the court clarified that the scope of protection of an SPC for A extends to any product containing A as long as the patent also confers that right (and as long as the MA is for A?). Yet in this respect also several questions remain.

Footnotes

1) Article 104(3) first subparagraph of the Rules of Procedure of the court, provides that where a question referred for a preliminary ruling is identical to a question on which the court has already ruled, or where the answer to such a question may be clearly deduced from existing case law, the court may, after hearing the Advocate General, at any time give its decision by reasoned order.

2) C–125/10, decision 8 December 2011, case 6 in Table 1.

3) All decisions can be found, by case number, on the court's website at http://curia.europa.eu/en/content/juris/c2–juris.htm or through eur-lex.

4) Medicinal products are defined as any substance or combination of substances presented for treating or preventing disease in human beings or animals and any substance or combination of substances which may be administered to human beings or animals with a view to making a medical diagnosis or to restoring, correcting or modifying physiological functions in humans or in animals (Article 1(a) SPC Regulation).

5) Regulation (EC) 1610/96 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 1996 concerning the creation of a supplementary protection certificate for plant protection products.

6) Obviously with the exception of the considerations regarding negative term SPCs.

7) For human use (2001/83/EC) or for a veterinary medicinal product (2001/82/EC) respectively.

8) C–392/97, September 1999. 9) Also referred to as the 'subject-matter test' or 'literal test'.

10) The disclosure test in itself also contained many different interpretations

between countries and even within the United Kingdom. 11) In so far as we can assess on the information publicly available to us.

12) In the United Kingdom, interpretations given to the 'disclosure test' differed between cases (between judges).

13) We checked the Spanish, German, French and Dutch decisions; in these languages the same verb is used in both the judgments and orders.

14) The Explanatory Memorandum to the proposal for a council regulation concerning the creation of a supplementary protection certificate for medicinal products of 11 April 1990, the predecessor of the present SPC Regulation, can be found at : https://sites.google.com/site/spccases/explanatory-memoranda/thememo.pdf?attredirects=0&d=1. This memorandum is considered relevant for the present SPC Regulation.

15) In the UK referral, possible non-compliance with Articles 3(c) and (d) was not an issue. In the parallel French proceedings, the SPC application was dismissed because the product had already been the subject of a certificate.

16) Paragraph 41.

17) Paragraph 34.

18) Paragraph 35.

19) Queensland paragraph 35 (emphasis added).

20) C–181/95 of 23 January 1997, paragraph 28.

21) Article 3(2): '2. The holder of more than one patent for the same product shall not be granted more than one certificate for that product. However, where two or more applications concerning the same product and emanating from two or more holders of different patents are pending, one certificate for this product may be issued to each of these holders.' This illustrates exactly what is meant to be excluded from protection by a certificate, It does not exclude the situation where one patent claims two different products in separate claims.

22) After referral, HC 14 February 2012.

23) Regulation 1768/92.

24) Regulation (EC) 1901/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2006 on medicinal products for paediatric use.

25) Paragraphs 42 and 43 of the decision in C–125/10.

26) Note 14 above, Considerations 20 and 38.

27) On 27 and 31 October 2011 in proceedings ex parte and inter partes respectively.

28) Paris Court of Appeal, 15 March 2011, Mylan and Qualimed v Dupont and Merck.

29) Paris Court of Appeal, 16 September 2011, Actavis v Novartis.

30) At the time of writing the order in C–574/11 was only available in German and French and the order in C–442/11 had been made available in English and French.

31) Consideration 21. In the German case in a similar consideration (19), the court mentions that the referring court established that Actavis's combination product infringed Novartis's valsartan patent.

32) As stated above, it should be noted that the 'disclosure test' in itself was the subject of different interpretations throughout Europe and even within countries; such was the case in the United Kingdom where the referrals originated. The court seems to have applied a strict interpretation of the 'disclosure test'.

33) 24 January 2012.

34) The text of the SPC as granted in Dutch is: 'Escitalopram, desgewenst in de vorm van een farmaceutisch aanvaardbaar zuuradditiezout, in het bijzonder escitalopramoxalaat'.

35) Consideration 19.2.

36) Consideration 19.2.

37) 10 February 2012.

38) [2011] EWCH 1669 (Pat).

39) See the judgment paragraphs 56 to 57.

40) 14 February 2012.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.