Clauses requiring a party to use best endeavours, reasonable endeavours, all reasonable endeavours and variations on the same theme, are commonplace in negotiated commercial contracts. There is a substantial body of case law dealing with the interpretation of these clauses. An obligation to use best endeavours is more onerous than reasonable endeavours, with all reasonable endeavours falling somewhere in between. However, there remains uncertainty as to the effort required by each type of clause in any particular case. That uncertainty is, at least in part, an inevitable consequence of the approach of the English courts to contractual interpretation.

This article considers:

- How the courts approach the construction of endeavours clauses.

- The prima facie meaning of the most commonly used endeavours clauses.

- The drafting of endeavours clauses.

A QUESTION OF CONSTRUCTION

The terms of an endeavours clause must be construed according to ordinary principles of contractual interpretation. This means that the clause must be construed against the relevant contractual and factual background, taking into account the other provisions of the contract and the commercial context at the time the contract was formed. In contrast, the question of whether the endeavours obligation has been satisfied will fall to be assessed by reference to the facts at the time of performance, which may not have been entirely foreseeable when the contract was drafted.

The importance of context

The High Court in Jet2.comLimited v Blackpool Airport Limited warned that the meaning of the expression "all reasonable endeavours" is a question of construction rather than extrapolation from other cases, and that the term will not always mean the same thing ([2011] EWHC 1529 (Comm); www.practicallaw.com/5-506-9888).

Arsenal Football Club v Reed is an example of a reasonable endeavours clause being construed in its commercial context ([2014] EWHC 781 (Ch)). Although the reasonable endeavours obligation appeared in a consent order rather than a contract, the principles are the same. Mr Reed sold Arsenal merchandise on his market stall and Arsenal Football Club brought trademark infringement proceedings against him. The proceedings were settled on terms that required Arsenal to use its reasonable endeavours to supply goods to Mr Reed at prices that were comparable to the lowest wholesale prices that Arsenal charged to other market traders. Arsenal stopped selling to market traders. Mr Reed said that this was a breach of the endeavours clause.

The High Court held that, taking into account the commercial context of the settlement, which was a mechanism for setting price, the endeavours clause qualified the obligation to supply in terms of delivery times, location, minimum quantities and so on rather than being an obligation to continue to supply indefinitely. It did not oblige Arsenal to continue in a market from which it wished to withdraw, particularly where, as here, it wished to do so for justifiable commercial reasons.

The importance of construing endeavours clauses against the contract as a whole is illustrated by Bristol Rovers (1883) Ltd v Sainsbury's Supermarkets Ltd ([2016] EWCA Civ 160; www.practicallaw.com/1-626-9911).Sainsbury's entered into a contract to buy a football stadium from Bristol Rovers Ltd in order to develop the site. The market changed and Sainsbury's sought to terminate the agreement if it lawfully could.

The agreement on the part of Bristol Rovers to sell and Sainsbury's to buy was subject to a condition that Sainsbury's would obtain acceptable planning permission before a certain date. The contract required Sainsbury's to use all reasonable endeavours to procure the grant of acceptable planning permission as soon as reasonably possible. The contract also contained detailed provisions setting out when Sainsbury's was required to appeal against a planning decision. Sainsbury's had no obligation to appeal unless advised by counsel that such an appeal had more than a 60% chance of success.

The local council resolved to grant planning permission but subject to a restriction regarding delivery hours. Sainsbury's and Bristol Rovers initially disputed whether the permission was an acceptable planning permission for the purposes of the contract. However, Bristol Rovers ultimately agreed to proceed on the basis that it was not an acceptable planning permission, due to the restriction on delivery hours, on condition that Sainsbury's would make a further application under section 73 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (section 73). The parties regarded that further application as an appeal for the purposes of the contract but agreed that it would be pursued without taking counsel's advice. That application was refused. Bristol Rovers argued that it omitted necessary detail, that there had been a failure to use all reasonable endeavours and that Sainsbury's should make a further application under section 73. Sainsbury's did not make a further application. Instead, by way of compromise, Sainsbury's lodged an appeal against the decision but then received advice that the appeal had a less than 60% chance of success. Sainsbury's withdrew the appeal and terminated the contract.

Bristol Rovers claimed that, by failing to make a further application under section 73, Sainsbury's had failed to use all reasonable endeavours in the planning process. The Court of Appeal held that Bristol Rovers was estopped from denying that the first section 73 application was an appeal under the contract. In those circumstances, Bristol Rovers could not assert that the failure to lodge a further application following the first failed appeal was a breach of Sainsbury's obligations. Sainsbury's was not obliged to lodge such an application unless counsel had advised that it passed the 60% test, and this had not occurred. The general obligation to use all reasonable endeavours was modified by the specific provisions in relation to appeals, and therefore Sainsbury's was entitled to terminate the contract.

Bristol Rovers is a good example of how a simple reasonable endeavours obligation can be complicated and modified not only by the other terms of the contract but by compromises which the parties may make regarding performance.

Unpredictable outcomes

There is a tension between the courts' approach that interpretation is sensitive to context and the point of view of the drafting lawyer who would like to be able to predict, with some degree of certainty, what the legal and commercial effect of a clause will be. The judgment of the Singapore Court of Appeal in KS Energy Services Ltd v BR Energy (M) Sdn Bhd includes an interesting discussion of that issue ([2014] SGCA 16). The court identified the problem as being that, while there is a wealth of case law in the various common law jurisdictions which provides some degree of insight, ultimately each case must be resolved on its own facts. The same endeavours clause, when used in different factual backgrounds, will not necessarily have the same or a similar meaning or implication.

The court concluded that it should generally assume that, in using similar phrases in their contract, the parties intended these phrases to bear their prima facie meaning. However, this presumption may be rebutted if there is a contrary and objectively ascertained intention on the part of the parties.

The court commented that previous decisions on the meaning and effect of commonly used phrases will provide authoritative guidance on the prima facie meaning of similar phrases when used in documents that are intended to have legal effect. In particular, this is because the parties would have taken into account the general law when reaching their agreement and because attributing prima facie meanings to similar phrases promotes commercial certainty.

It is encouraging to see judicial sympathy for the requirement of certainty in interpreting commonly used phrases but it is unclear whether the concept of "prima facie meanings" takes matters much further. Adopting the approach to construction applied by the English courts, the primary source for understanding what the parties meant is the words that the parties have chosen interpreted in accordance with conventional usage; that is, words are given their prima facie meaning. However, the problem of unpredictable outcomes is not helped by the differences in approach between those judges who favour a more traditional and literal approach to interpretation and those who are more interventionist and purposive in their approach (see News brief "Contract interpretation: the Supreme Court's last word (for now)?", www.practicallaw.com/1-641-0887).

Filling in the gaps

Where the requirements of an endeavours clause are not clear, the court may impose its own value judgment as to what is required. That was recognised expressly in the recent decision in Astor Management AG and another v Atalaya Mining plc and others ([2017] EWHC 425 (Comm); www.practicallaw.com/7-640-9956).

Atalaya Mining plc (Atalaya) had bought Astor Management's interest in a dormant copper mine. The payment of most of the consideration was deferred until Atalaya secured a senior debt facility. Atalaya was required to use all reasonable endeavours to obtain the debt facility by a certain date. Atalaya failed to obtain the facility but instead raised funds from its parent company and restarted mining. Astor Management argued that the payment of the deferred consideration had been triggered. One of the issues for the High Court to decide was whether, as Atalaya argued, the endeavours obligation was void for lack of certainty (see also box "Astor Management and good faith").

Before Astor Management, there had been a number of cases dealing with the enforceability of so-called agreements to agree which demonstrated that the courts were increasingly willing to give legal effect to contractual provisions even when they are expressed in very wide or open-ended language. The court in Astor Management cited four clear and authoritative decisions in support of that proposition, the most recent being Durham Tees Valley Airport v bmibaby in which the Court of Appeal observed that where parties intend to create a contractual obligation, the court will try to give it legal effect ([2010] EWCA Civ 485). The court will only hold that the contract, or some part of it, is void for uncertainty if it is legally or practically impossible to give to the agreement, or that part of it, any sensible content (citing Scammel v Dicker ([2005] EWCA Civ 404)).

However, in cases concerning endeavours clauses before Astor Management the courts were not as consistent in their approach to the question of whether an endeavours clause was void for want of certainty. In Jet2.com, a contract between Jet2.comand Blackpool Airport stipulated that Blackpool Airport was under an obligation to use:

- Best endeavours to promote Jet2.com's low-cost services from Blackpool Airport.

- All reasonable endeavours to provide a cost base that would facilitate Jet2. com's low-cost pricing.

The Court of Appeal found that the obligation to promote Jet2.com's low-cost business was not so uncertain as to be incapable of enforcement ([2012] EWCA Civ 417; www.practicallaw.com/0-519-6252). It noted that there is an important distinction between a clause where the content is so uncertain that it is incapable of creating a binding obligation and a clause that gives rise to a binding obligation, the precise limits of which are difficult to define in advance, but which can nonetheless be given practical content. A contractual obligation to buy a van on terms that part of the price should be paid on hire-purchase terms over a period of two years would be an example of the former. An obligation to promote the sale of a product would fall within the latter category and was not so uncertain as to be incapable of giving rise to a legally binding obligation.

There was more doubt as to the enforceability of the obligation to provide a cost base that would facilitate Jet2.com's low-cost pricing, with the court stating that the words were too opaque to enable it to give them that meaning with any confidence. However, this was ultimately not relevant to the court's decision.

In contrast, in Dany Lions Ltd v Bristol Cars Ltd, the High Court found that an endeavours clause was too uncertain to enforce ([2014] EWHC 817 (QB)). Dany Lions Ltd bought a classic car from Bristol Cars Ltd on the understanding that it would be restored. After the restoration works failed to progress, the parties entered into a settlement agreement which included a condition precedent under which Dany Lions was to use its reasonable endeavours to enter into an agreement with a particular third-party specialist restorer, Jim Stokes Workshops Limited, before a specified date. The condition precedent was not satisfied and Dany Lions sought damages against Bristol Cars under the original agreement. In its defence, Bristol Cars argued that Dany Lions was in breach of the obligation to use its reasonable endeavours under the condition precedent.

The court considered whether the obligation to use reasonable endeavours to contract with Jim Stokes was enforceable. It held that an endeavours clause will only be enforceable if both:

- The object of the endeavours is sufficiently certain.

- There are sufficient objective criteria by which to evaluate the reasonableness of the performance of the endeavours.

The court took the view that these criteria could never be satisfied in a case in which the object is a future agreement with the other contracting party. If the object were a future agreement with a third party, the criteria might be satisfied but these cases are likely to be exceptional and the essential terms of the prospective agreement with the third party would probably need to be identified in advance. If the terms of the future agreement were left open for negotiation, it is likely that the clause would be unenforceable for lack of sufficient objective criteria by which the reasonableness of the endeavours could be evaluated. On that basis, the court found the clause in Dany Lions to be too uncertain to be enforceable, since the parties had left open the question of the price and other terms.

The approach in Astor Management

In Astor Management, Atalaya sought to rely on Dany Lions, arguing that the endeavours clause was unenforceable because it failed to satisfy the second requirement in Dany Lions; that is, there were no objective criteria by which the court could judge the reasonableness of its endeavours to obtain the senior debt facility. The court could not, for example, determine whether or not it ought reasonably to have pursued a negotiation with a particular lender, or accepted a given offer, or proposed a lower interest rate, as this would potentially require the court to make an unlimited number of minute commercial judgments, which no court would be in a position to do.

The court in Astor Management rejected the approach in Dany Lions, in so far as that decision suggests that requirements of certainty of object and sufficient objective criteria are difficult to satisfy and will not usually be satisfied where the object of an endeavours clause is an agreement with a third party. On the contrary, a clause of this kind should almost always be capable of being enforced. The court noted that its role in a commercial dispute is to give legal effect to what the parties have agreed, not to refuse to do so because the parties have not made it an easy task. It would be the court's last resort to hold that a clause is too uncertain to be enforceable.

In the court's view, far from being exceptional it should almost always be possible to give sensible content to an undertaking to use reasonable endeavours (or all reasonable endeavours or best endeavours) to enter into an agreement with a third party. Whether the obligor has endeavoured to the required standard to make such an agreement is a question of fact which the court can decide perfectly well. The court went on to say that, where parties have adopted a test of reasonableness, they appear to be deliberately inviting the court to make a value judgment, and this sets a limit to their freedom of action. On matters of fine commercial judgment, it may be difficult to establish a breach but it does not follow from the fact that there may be difficulty in proof that there is no obligation at all or that the obligation has no sensible content.

On the facts of Astor Management, there was no breach of the reasonable endeavours clause because Atalaya was not required to obtain a senior debt facility at any cost or which would make the project commercially unviable. Ultimately, there was insufficient evidence to make the case that a senior debt facility on suitable terms was available.

The approach of the court in Astor Management to endeavours clauses seems more likely to be preferred in future cases than the approach in Dany Lions because it is more in line with the direction of travel when it comes to issues of certainty. Recent cases show the courts' increasing willingness to give effect to contractual provisions that traditionally may have been found to be void for uncertainty. For instance, in Emirates Trading Agency LLC v Prime Mineral Exports Private Ltd, the High Court held that an agreement to seek to resolve a dispute "by friendly discussion" before referring it to arbitration created an enforceable obligation ([2014] EWHC 2104 (Comm);www.practicallaw.com/3-578-7936).

If that is correct then using a standard endeavours clause is, in effect, a decision to accept the risk of a court determining what steps should be taken to satisfy the obligation, taking into account the relevant contractual and commercial context. In complex and highly specialised areas of business, that is a decision that should not be taken lightly. The bigger the gaps, the more scope there is for unintended consequences.

PRIMA FACIE MEANINGS

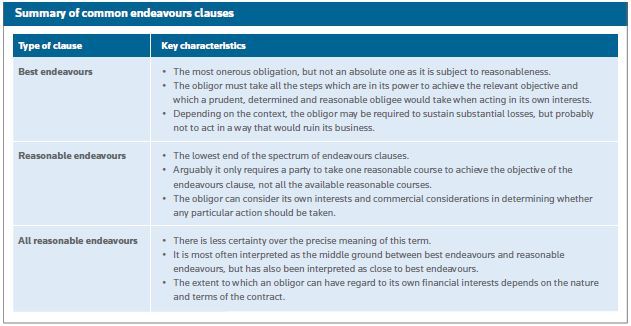

How much is left to be decided by a court when confronted with an endeavours clause will depend on the particular circumstances but some prima facie meanings of the different endeavours clauses have emerged through case law (see box "Summary of common endeavours clauses"). However, there are still grey areas, especially concerning the scope of "all reasonable endeavours". Frustratingly for those looking for certainty, "it depends" is the right answer to many of the most important questions.

Best endeavours

The courts have historically recognised "best endeavours" as the most onerous endeavours formulation. An obligation to use best endeavours is typically interpreted as requiring the obligor to take all the steps that are in its power which are capable of producing the desired results, being the steps that a prudent, determined and reasonable obligee would take when acting in its own interests and desiring to achieve that result (IBM United Kingdom Limited v Rockware Glass [1980] FSR 335).

In other words, the obligor must pursue the objective on the obligee's behalf as assiduously as the obligee would do itself. In Sheffield District Railway Co v Great Central Railway Co, the Rail and Canal Commissioners, chaired by Mr Justice Lawrence, said that the obligor must, broadly speaking, leave no stone unturned in its endeavours to achieve the objective ([1911] 27 TLR 451). The phrase "best endeavours" means what the words say; they do not mean second-best endeavours.

While an undertaking to use best endeavours places a heavy burden on the obligor, it stops short of being an absolute obligation to perform. In Pips (Leisure Productions) Ltd v Walton, it was held that best endeavours are considerably more than casual and intermittent activities but less than efforts which go beyond the bounds of reason ([1982] 43 P&CR 415). In the same case, the relevant standard was expressed as at least "the doing of all that reasonable persons reasonably could do in the circumstances".

In Midland Land Reclamation v Warren Energy Limited, the High Court also stressed that the duty imposed by a best endeavours obligation is subject to reasonableness ([1997] EWHC 375 (TCC)). It rejected the argument that it is the next best thing to an absolute obligation or guarantee.

Whether, and to what extent, a person who has agreed to use best endeavours can have regard to its own commercial interests is not clear cut. In certain circumstances, the obligor may be required to sustain substantial losses. The extent to which it is required to do so will depend on the nature and terms of the contract. In Jet2.com, the Court of Appeal considered whether, under an obligation to use best endeavours to promote Jet2.com's low-cost airline business, Blackpool Airport had to continue to accept flights outside its normal opening hours. The majority of the court concluded that it must, even though it suffered a loss each time it did so. Aircraft movements outside normal hours were essential to Jet2.com's business and were therefore fundamental to the agreement.

In Terrell v Mabie Todd & Co Ltd, the court held that a best endeavours obligation did not require the directors to act in a way that would ruin the company or to act in complete disregard of the interests of the shareholders, but only to do what could reasonably be done ([1952] 69 RPC 234). In Jet2.com, the court observed that the specific context in which the undertaking was given in Terrell made it clear that the directors were expected to do no more than could reasonably be expected of a reasonable and prudent board of directors acting properly in the interests of the company. However, it indicated that, even on the very different facts in Jet2.com, the sacrifices required of the obligor were not without limit: were it to become clear that the airline could never expect to operate low-cost services from Blackpool at a profit, it suggested that Blackpool Airport would not be obliged to incur further losses in seeking to promote a failing business.

A party that has agreed to use best endeavours may, depending on the circumstances, be required to litigate or pursue an appeal against a decision. However, it is unlikely that the obligor would be required to litigate where a claim is demonstrably hopeless (Malik Co v Central European Trading Agency Ltd [1974] 2 Lloyd's Rep 279).

Reasonable endeavours

An obligation to use reasonable endeavours places a much lower burden on the obligor than an obligation to use best endeavours. It has been said that it sits at the lowest end of the spectrum of endeavours clauses (Jolley v Carmel Ltd [2000] 3 EGLR 68).

The widely accepted explanation of the differences between best and reasonable endeavours was given by Mr Julian Flaux QC in obiter comments in Rhodia International Holdings Ltd v Huntsman International LLC ([2007] EWHC 292; see Briefing "Should you endeavour to be reasonable?", www.practicallaw.com/9-364-6026). He said that an obligation to use reasonable endeavours probably only requires a party to take one reasonable course to achieve the aim, whereas an obligation to use best endeavours probably requires a party to take all of the reasonable courses it can in order to achieve that aim.

Moreover, once the obligor correctly takes the view that it can do nothing further in terms of reasonable steps to achieve the objective, it is no longer obliged to try (Dany Lions).

A further distinction between best endeavours and reasonable endeavours lies in the extent to which the obligor may have regard to its own commercial interests. The fulfilment of a reasonable endeavours obligation may, in some cases, require the obligor to commit to some limited level of expenditure. However, the obligor is entitled to balance the obligation to use reasonable endeavours against all relevant commercial considerations (including cost and any uncertainties or practicalities relating to compliance) and to weigh up the likelihood of succeeding in the endeavour before taking any particular course. These considerations are likely to be based on the specific circumstances of the obligor, and the obligor is entitled to look first and foremost, if not only, to its own interests in determining whether any particular action should be taken (UBH (Mechanical Services) Ltd v Standard Life Assurance Company, The Times, 13 November 1986).

All reasonable endeavours

Of the three most common types of endeavours clause, there is least certainty regarding the meaning of "all reasonable endeavours". Traditionally, it was viewed as a middle position somewhere between best and reasonable endeavours, implying something more than reasonable endeavours but less than best endeavours (UBH (Mechanical Services) Ltd).

Rhodia International cast some doubt on this position. In its judgment, the High Court commented that an obligation to use reasonable endeavours to achieve the aim probably only requires a party to take one reasonable course, not all of them, whereas an obligation to use best endeavours probably requires a party to take all the reasonable courses it can. The court said that, in that context, it may well be that an obligation to use all reasonable endeavours equates with using best endeavours.

This has sometimes been interpreted as meaning that best endeavours and all reasonable endeavours are effectively indistinguishable in all respects. However, the obiter comments in Rhodia International have also been taken to refer more narrowly to the number of courses of action that an obligor is required to take. Following this approach, all reasonable endeavours has some similarities with best endeavours; that is, all reasonable avenues must be exhausted, but also some features in common with reasonable endeavours; that is, the obligor is not necessarily required to prejudice its own commercial interests.

In EDI Central Limited v National Car Parks, the Scottish Court of Session concluded that "all reasonable endeavours" means that the obligor will be expected to explore all avenues reasonably open to it, and to explore them all to the extent reasonable but, unless the contract otherwise stipulates, the obligor is not required to act against its own commercial interests ([2010] CSOH 141).

In CPC Group Ltd v Qatari Diar Real Estate Investment Co, the High Court also found that a duty to use all reasonable endeavours does not always require the party to sacrifice its commercial interests, although this implies that sometimes it may ([2010] EWHC 1535 (Ch)) (see box "Other forms of endeavours wording").

In Jet2.comthe court held that the question of whether, and to what extent, a party that has undertaken to use best endeavours can have regard to its own financial interests depends on the nature and terms of the contract. In Astor Management, the court likewise took the view that the same approach must equally apply to the question of what constitutes all reasonable endeavours.

DRAFTING

In his judgment in Re Sigma Finance Corp (In Administration), Lord Neuberger, sitting in the Court of Appeal, gave an interesting insight into the judicial view of the mindset of the drafting lawyer ([2008] EWCA Civ 1303). Observing that documents are prepared in many different ways, he said that they often have provisions lifted from other documents, provisions inserted or amended by different lawyers at different times and last-minute amendments agreed in a hurry (often in the early hours of the morning after intensive negotiations) with a view to achieving finality rather than clarity. He commented that the skill of the lawyer is often in producing obscurity rather than clarity so that the parties, who have inconsistent interests, can feel satisfied with the result.

Many will take issue with the suggestion that the drafting lawyer's skill is in producing obscure meanings to close the deal. However, the amount of case law generated by commonly used endeavours clauses lends support to the view that, while these clauses are a useful way of dealing with complicated and potentially contentious issues, this may be at the expense of clarity and certainty.

To mitigate that problem, assuming that the goal of the drafting lawyer is not simply producing obscurity rather than clarity, he should consider setting out in the contract particular steps that the obligor is, or is not, expected to carry out to satisfy the particular endeavours obligation (see box "Drafting tips"). The steps that the parties may want to address expressly in the contract will depend on the context but might include, for example, whether an obligor must bear any costs or incur any expenditure in seeking to comply with the endeavours clause and, if so, how much.

Endeavours clauses remain a practical solution to a difficult problem and are sometimes the only practical solution regardless of how much time is available to negotiate. However, using a standard formulation without adding some further direction may leave too much to be interpreted by a court with far less knowledge of the commercial realities than the parties. That introduces an unwelcome degree of uncertainty for both parties and invites argument which may be more difficult to resolve once the contract has reached the point of performance.

Endeavours Clauses - Striving For Certainty

This article first appeared in the June 2017 issue of PLC Magazine.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.