The United States Supreme Court's recent decision in UARG v. EPA offers insight as to how future courts will evaluate the authority of the Environmental Protection Agency ("EPA") under the Clean Air Act ("CAA") to regulate greenhouse gas ("GHG") emissions from power plants and other stationary sources. In UARG, EPA had interpreted the CAA, through the Tailoring Rule, as requiring Prevention of Significant Deterioration ("PSD") and Title V permitting on the sole basis of a source's potential to emit GHGs.

The Supreme Court rejected this interpretation, holding that Congress must "speak clearly if it wishes to assign to an agency decisions of 'vast economic and political significance.'" Thus, the takeaway from UARG is that EPA rulemaking—especially rulemaking that would bring about an "enormous and transformative expansion in EPA's regulatory authority"—must be grounded in and judged against the statutory text of the CAA.

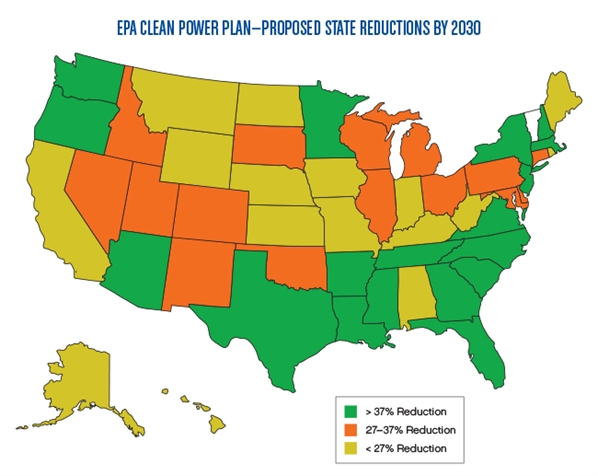

EPA's recent proposal to establish GHG emission guidelines for existing power plants under CAA § 111(d) is likely to test the standard set by the Supreme Court in UARG. Like the Tailoring Rule, the proposed guidelines will have significant economic and political impacts. Forty-nine states will need to achieve GHG emission reductions ranging from 11 to 72 percent by 2030 (see map below). Even by EPA's own estimates, the costs of compliance with the guidelines are expected to reach $7 billion to $8 billion annually by 2030.

In addition, the guidelines represent an unprecedented expansion of

EPA authority in several ways. While § 111(d) requires EPA to

"establish a procedure" for states to submit plans with

standards of performance for existing sources, it fails to specify

how detailed the EPA procedure should be or suggest whether EPA can

require states to achieve a particular standard of performance. In

the proposed guidelines, EPA purports to require compliance with

specific statewide GHG emission standards in pounds per

megawatt-hour. EPA also utilizes § 111(d) more expansively

than ever before by proposing measures that extend outside of

individual sources in the regulated source category, such as

setting statewide emission reduction targets, regulating state

efforts to increase renewable energy capacity, and prescribing an

increase in state demand-side energy efficiency efforts. This

"beyond the fence" approach is not apparent from the

statutory text of § 111(d) and, in practice, would extend the

reach of the guidelines to many sources outside of the regulated

category.

Though UARG does not touch on EPA's § 111(d)

rulemaking authority, the decision emphasizes the need for EPA to

base its rulemakings in explicit statutory authority.

The question that EPA must address, and future courts will have to

resolve, is whether

§ 111(d) provides "clear congressional

authorization" to support the proposed guidelines for existing

power plants. In UARG, the Supreme Court noted that it is

skeptical "[w]hen an agency claims to discover in a

long-extant statute an unheralded power to regulate a significant

portion of the American economy." Given the unusual scope and

significance of the proposed guidelines, EPA will need to identify

specific provisions of § 111(d) that justify its proposed

approach.

Jane K. Murphy - Editor

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.