The patent application examination requirement is statutory based rather than a Constitutional requirement. For instance, from 1793 to 1836, the U.S. Patent System operated on a registration system without examination. Since the passage of the Leahy–Smith America Invents Act (AIA), the number of new patent applications filed each year has exceeded 500,000, while the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) is reversing Patent Office Examiners' approvals at a staggeringly high rate.

The author proposes that examination be performed or required only after it has been determined that the patent application will be enforced. This procedural change in the timing of Patent Office examinations will have several advantages discussed below.

The U.S. Constitution provides:

The Congress shall have the power . . . to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries. U.S. Const. art. I, §8, cl. 8.

The Patent Office's existing modus operandi is to examine every patent application—even if the invention is not likely to contribute to society—with no way to prioritize its resources to focus on inventions that are important and may contribute to society.

This obligation to examine every patent application is based on the patent statutes and does not originate in the Constitution. For example, from 1790 to 1793, the U.S. patent system required examination. However, from 1793 to 1836, the U.S. patent system did not conduct any examination and was merely a registration system. Currently, 35 U.S.C. Section 131 is the basis for this ex parte examination requirement, and it states:

The Director shall cause an examination to be made of the application and the alleged new invention; and if on such examination it appears that the applicant is entitled to a patent under the law, the Director shall issue a patent therefor.

This statute places the obligation on the Patent Office to prove why an invention is not patentable. This is important because under the existing system, every patent application must be examined. With an average lag time of three to five years for a patent application to be examined and issued, combined with the over 500,000 new applications filed annually, there may be 1.2 million to 2 million patent applications in the examination queue.

The Patent Office has often complained about the significant workload that it has experienced because of the tremendous number of patent applications filed each year. To date, patent reform efforts have addressed possible changes to the patent system on the back end of the patent process. That is to say, to date, the tail has been wagging the dog.

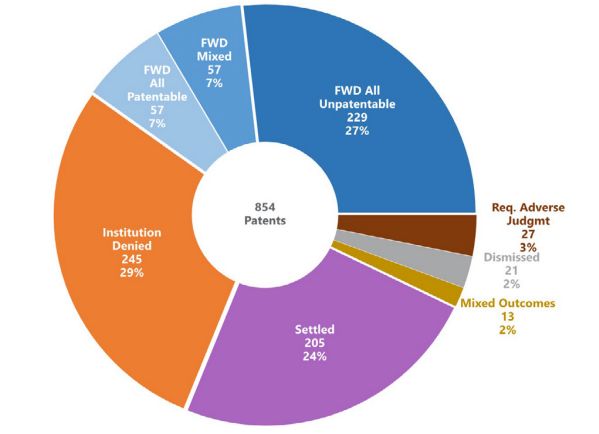

To reduce the problem, the Patent Office budget has significantly increased, with the result that the total pendency time has begun to creep down. However, any little stumble by the Patent Office will likely result in significant increases in pendency. In addition, as discussed below, with the passage of the AIA,1 one has to wonder whether ex parte examination is needed at all. That's because patent examiners for ex parte examination have a modest budget of hours they can spend on each patent application to perform their duties in assessing the patentability of an invention.2 With the passage of the AIA, however, as will be explained below, Patent Office examiners have made at least one error in at least 64% of the patents reviewed. This shocking statistic likely reflects the reality that the limited-time budgets for examination are inadequate and may never be adequate.

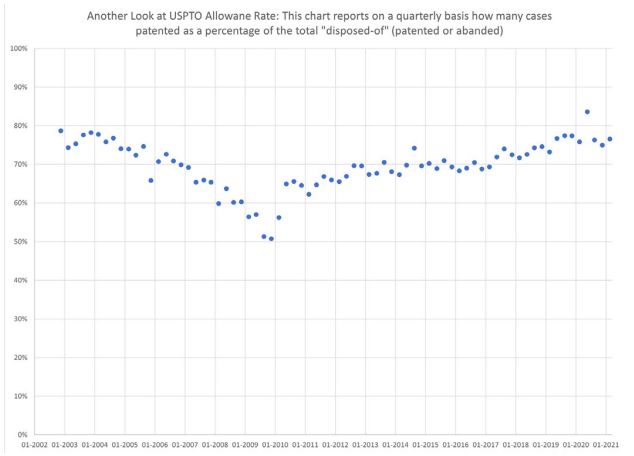

Let's take this analysis one step at a time. The current allowance rate for patent grant on average is above 60%–65%:3

The "reversal" rate at the PTAB for contested proceedings under the AIA (principally inter partes reviews—IPRs) after a patent has been granted is arguably unacceptably high. After a final written decision (FWD), the patent owner fully wins and all claims at issue are held patentable only 7% of the time:4

However, government officials are presumed to perform their duties in a correct manner. Thispresumption of validity likely originated with Justice Story over 180 years ago in the Supreme Court's opinion in The Philadelphia and Trenton Railroad Company v. Stimpson:

The patent was issued under the great seal of the United States, and is signed by the President, and countersigned by the Secretary of State. It is a presumption of law, that all public officers, and especially such high functionaries, perform their proper official duties until the contrary is proved. And where, as in the present case, an act is to be done, or patent granted upon evidence and proofs to be laid before a public officer, upon which he is to decide, the fact that he has done the act or granted the patent, is prima facie evidence that the proofs have been regularly made, and were satisfactory.5

35 U.S.C. §282, which was a codification of this presumption of validity, reads:

(a) In General.—

A patent shall be presumed valid. Each claim of a patent (whether in independent, dependent, or multiple dependent form) shall be presumed valid independently of the validity of other claims; dependent or multiple dependent claims shall be presumed valid even though dependent upon an invalid claim. The burden of establishing invalidity of a patent or any claim thereof shall rest on the party asserting such invalidity.6

A defendant/accused infringer seeking to overcome this presumption of validity must persuade the factfinder of its invalidity defense by clear and convincing evidence. Judge Rich, a principal drafter of the 1952 Patent Act, articulated this view in American Hoist & Derrick Co. v. Sowa & Sons, Inc.7

So, what is going on at the PTAB? And if patents are going to be so frequently invalidated, does the Patent Office need to budget more hours for examiners to do a more thorough examination?

Clearly, the AIA has had a historic impact on the validity of U.S. patents, violently shifting the U.S. patent system from somewhat favoring the inventor to a system that heavily favors the challenger. It's likely that at least one significant reason for this shift is that contested proceedings under the AIA do not provide the patent owner with this presumption of validity. Interestingly, the Patent Office has stated that there is no presumption that it did its job correctly, ignoring Justice Story's common law presumption.8

Thus, today, when an accused infringer is sued in federal court, most invalidity challenges are being waged at the Patent Office via the AIA contested proceedings, where there is no presumption of validity and where the challenger is heavily favored to invalidate the patent. The AIA contested proceedings have arguably resulted in the overall view that initial (ex parte) examination at the Patent Office is not effective and that expending resources on millions of patents seems a waste of government resources and taxpayer dollars! That is, if the Patent Office is not going to be allocated sufficient resources for its examiners to properly examine patent applications/ inventions—and if the presumption of validity is not going to be honored by the Patent Office in reviewing its own work, i.e., if the presumption of validity is dead—then do we need the initial (ex parte) examination at the U.S. Patent Office?

The Proposed Solution

For the Patent Office to effectively examine patent applications/inventions to determine which should receive the award of the patent grant, Patent Office resources must be allocated based on this priority. Today, Patent Office resources are not prioritized, and therefore the Patent Office expends a significant amount of its resources on patent applications/ inventions that never contribute to or benefit society.

So how can Patent Office resources be prioritized? If substantially more funds are not going to be allocated to the current examination process, then perform an examination only after it has been determined that the registered patent (or in limited circumstances, a patent issued via the traditional examination process described below) will subsequently be enforced.

How can it be determined that a registered patent will subsequently be enforced? One answer to this question can be to require the patent registration owner to file an "intent to enforce" notification identifying at least one intended defendant,9 which holds the patent owner accountable for initiating civil litigation over the patent once/if the registered patent is issued after Patent Office examination or provides some penalty for not enforcing the patent after a specific time period.

Small businesses and individuals could optionally request a substantive examination in advance. Receiving such an examination as opposed to just a registered unexamined patent might be of greater importance to investors in and/or competitors of such smaller enterprises or individuals. However, should the small business or individual choose to later enforce the patent, a notice of intent to enforce and an additional examination would still be required before an infringement litigation could proceed past the filing of the complaint.10

Rather than classify patent applications as pending, the Patent Office would instead issue a patent registration certificate, which would have features similar to pending patent applications and issued patents. When owners file the intent to enforce, the USPTO can then conduct an ex parte review, subject to certain exceptions described above.

This procedural change in the timing of Patent Office examination would have several advantages, which I also detailed in a recent article in Bloomberg Law on reforming the patent system. Other benefits include:

- Overall examination volume would be significantly reduced.

- Patent applications that are more likely to have an impact on society would get a more focused share of the Patent Office's already limited resources.

- The Patent Office would be able to provide competitive compensation packages for its employees, thereby reducing the attrition rate that has plagued the office over the past decade or more.

- The patent registration certificate would allow inventors to perfect a patent filing by providing the constructive reduction to practice.

- A patent applicant would not obtain a presumption of validity for issuance of the registration certificate; the presumption of validity would only be awarded after examination.

- The prior art search would not have to be restricted to a specific hourly budget but could be expanded as needed without repercussions for examiners.

- Applicants would still benefit from priority, and reduction to practice with certificates. Obtaining a speedy reduction to practice to perfect an applicant's priority date is even more important today, since the enactment of the AIA.

- Publication of patent application filings would occur immediately (with the potential exception of small entities), thereby eliminating delays in providing knowledge and research to society.

- Independent inventors and small entities would see significantly reduced overall filing fees and costs in pursuing a patent registration certificate. Filing fees for post-registration examination could be adjusted in a manner that balances promoting the public interest and encouraging innovation and use of the patent system.

- A Patent owner would be permitted to enlarge the scope of the claims11 in post-registration examination. Because the intent-to-enforce notice would have to identify future defendants, those parties would have the opportunity to participate in the examination.

I welcome constructive comments and suggestions regarding the above proposal and/or any other suggestions to improve the U.S. patent system.

Footnotes

1. Leahy–Smith America Invents Act (AIA), Pub. L. No. 112–29, §6(a), 125 Stat. 284, 299 (2011).

2. An examiner's time budget for reviewing the patent application and invention and issuing a first Office Action is generally less than 25 hours, although there may be situations in which an examiner is permitted to spend more time with prior approval.

3. https://patentlyo.com/patent/2021/04/another-uspto-allowance.html.

4. https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ptab_aia_fy2022_q3__roundup.pdf.

5. The Philadelphia and Trenton Railroad Company v. Stimpson, 39 U.S. (14 Pet.) 448, 458–59 (1840) (Story, J.) (emphasis added). Justice Story even went one step further, saying, "No other tribunal is at liberty to re-examine or controvert the sufficiency of such proofs, if laid before him, when the law has made such officer the proper judge of their sufficiency and competency." Id., at 458–59. 35 U.S.C. §282 provides defenses to claims of patent infringement in federal court subject to this presumption.

6. 35 U.S.C. §282 (emphasis added).

7. American Hoist & Derrick Co. v. Sowa & Sons, Inc., 725 F.2d 1350, 220 U.S.P.Q. 763 (Fed. Cir. 1984).

8. To date, there has been no assertion that the presumption of validity should apply in AIA contested proceedings based on Justice Story's common law presumption.

9. In addition to the notice of intent to enforce the option to obtain a full examination, there could be a notice of intent to sell or license an invention, which could be exercised as such an option. The details of such an additional option would require additional consideration but could be limited to, e.g., individuals, micro entities and small entities.

10. See the following paper by Mark Lemley, et al., advocating a voluntary "gold plated" examination process that would generate a stronger presumption of validity: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=869826.

11. A similar argument can be made to allow the patent owner to enlarge claims during contested post-issuance proceedings under the AIA, where, as indicated above, patent owners appear to be severely prejudiced and relatively unsuccessful compared to their success during ex parte examination.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.