On November 28, 2022, the Council of the European Union (Council) gave its final approval to the proposed Regulation on Foreign Subsidies (Regulation), concluding seven months of negotiations with the EU Parliament. Under this Regulation, the European Commission (EC) will have powerful new tools to investigate foreign subsidies that distort competition in the European Union. The new toolbox aims to ensure a level playing field between EU-based companies, which must comply with strict domestic (intra-European Union) rules on subsidies, and foreign actors that do not.

The Regulation is expected to be published in the Official Journal of the EU later this month or in early 2023. It will enter into force on the 20th day following its publication and apply six months after that, i.e., around mid-2023.

The Regulation could be a game changer for companies doing business in Europe, including those making foreign direct investments (FDIs) or multinationals competing for international contracts. It is likely to seriously increase the red tape and risks for any company established, operating or investing in the European Union with support from non-EU countries. At the same time, it might also be weaponized by competitors that want to interfere with a deal they oppose.

Main provisions of the Regulation

We have previously reported on the Regulation's provisions, based on the EC's proposal. Most of the provisions in the proposal have found their way into the final text of the Regulation. The most important changes reduce the review periods and add a new threshold for public procurement, as well as reduce the initial 10-year time limit for the review of foreign subsidies granted before application of the Regulation. In short, the main provisions of the Regulation are as follows:

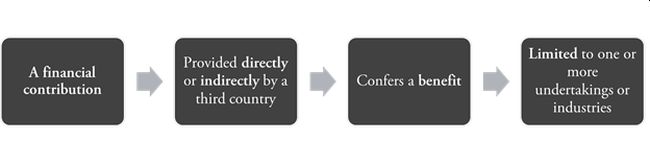

- The concept of "subsidy" under the Regulation. A foreign subsidy is defined based on four cumulative conditions:

- The concept of subsidy is very broad, and the Regulation will apply to all non-EU countries. Possible examples of subsidies captured under the Regulation include direct financial grants, preferential loans, corporate tax benefits and non-market-based government transactions.

- The Regulation will apply to all types of economic activity in the European Union. The Regulation will apply to all businesses that invest in the European Union, participate in government procurement or are otherwise active in the European Union. It also covers EU multinationals that receive government support outside the European Union. The Regulation does not cover businesses that operate exclusively outside the European Union and do not seek to acquire EU companies or participate in EU procurement procedures.

- The Regulation is concerned with distortive effects of foreign subsidies. Like EU State aid rules, the Regulation targets subsidies that improve the competitive position of the recipient in the European Union and impact competition in the European Union. The new rules are intended to catch and sanction any subsidies that are deemed distortive.

- Relationship to the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM Agreement). Article 44(9) of the Regulation clarifies that "no action shall be taken under this Regulation which would amount to a specific action against a subsidy within the meaning of Article 32.1 of the [SCM Agreement] and granted by a third country which is a member of the [WTO]." Third-country subsidies covered by the SCM Agreement, which applies to trade in goods, are also covered by EU Regulation 2016/1037 on protection against subsidized imports from countries that are not members of the European Union. It remains to be seen how the new Regulation on Foreign Subsidies and Regulation 2016/1037 will interact in practice and how the EC will seek to comply with the SCM Agreement in this context.

The Regulation provides for ex ante and ex post investigations of foreign subsidies

a. Prior notification of transactions. M&A deals must be notified prior to completion if:

i. At least one of the merging parties, the acquired party or the joint venture is established in the European Union and its EU groupwide turnover is at least €500 million; and

ii. The aggregate financial contribution the parties (and affiliates) received from foreign governments exceeded €50 million in the prior three calendar years. The financial contribution does not have to fulfill the other criteria of a "foreign subsidy" within the meaning of the Regulation, thus casting a broader net for required notifications.

This comes on top of existing merger control and foreign direct investment filing obligations. The proposed procedural rules under the Regulation are very similar to those applying to EU merger control.

b. Prior notification in government procurement. When bidding for contracts worth at least €250 million, bidders must notify all aggregate foreign financial contributions of at least €4 million per third country that they and their main subcontractors and suppliers received in the prior three calendar years.

In addition, the European Parliament and the Council have introduced a new threshold in the final text of the Regulation. Where the contracting authority divides a procurement into lots, foreign financial contributions will be notifiable only if the aggregate value of all lots for which the bidder applies is at least €125 million.

Even if these thresholds are not met,

bidders must still list the foreign financial contributions

received in the past three years and confirm that they are not

notifiable. Generally, the contract may not be awarded before the

EC finishes its review; this can take up to 160 working days

(instead of the originally proposed 260 days) from the receipt of a

complete notification.

c. Catch-all tool. The EC can investigate all other market situations (e.g., greenfield investments, other transactions below the notification thresholds, normal-course competition in an EU services market) where it suspects that a foreign subsidy distorts competition in the European Union. The applicable procedural provisions are similar to the European Union's countervailing duty rules.

Other important provisions of the Regulation

Temporal application: The Regulation applies to foreign subsidies granted in the five (instead of the originally proposed 10) years prior to its date of application where such subsidies distort the EU internal market after its date of application.

Balancing test: In deciding whether a foreign subsidy infringes the Regulation, the EC may balance the negative effects of a foreign subsidy in terms of distortion in the internal market against its positive effects on development of the subsidized economic activity in the internal market, while considering other positive effects of the foreign subsidy, such as the broader positive effects in relation to relevant EU policy objectives.

The Regulation does not state whether positive effects occurring outside the EU internal market (e.g., mitigation of climate change) may be taken into account. The evolution of the relevant provisions of the Regulation during the EU legislative process, as well as the fact that the negative effects to be assessed in the context of the balancing test are only those in the internal market, suggests that the positive effects also must occur within the internal market. However, the Regulation remains unclear on this point—it remains to be seen whether it will be subsequently addressed in the "initial clarifications" or guidelines to be issued by the EC (see below).

Potentially severe remedies and sanctions: The EC can prohibit M&A transactions and the award of government contracts, as well as order the dissolution of M&A transactions. It can also impose remedies on the companies. Noncompliance can trigger fines of up to 10% of the groupwide aggregate turnover (aside from reputational risks).

Key implications for business

The Regulation is expected to significantly change the way companies that receive foreign support do business in the European Union. Some key takeaways include the following:

a. Risk assessment: Those companies that have received foreign subsidies and plan acquisitions and/or public procurement bids in the European Union need to assess what the proposed new rules could mean for them. In other words, they should (i) gather information about what subsidies they have received in the past five years or will receive in the future, (ii) review whether they could face new EU filings or interventions, and (iii) assess whether such filings or interventions could impact their business plans.

b. Compliance and due diligence: In-house counsel may want to start thinking about preparing internal compliance systems to ensure their businesses are aware of what may be coming; assessing what information may be required for notifications and investigations, including information considered sensitive or confidential in their national jurisdictions; and establishing tools to collect the groupwide financial contribution and subsidy information needed to comply with the notification obligations.

c. Reputational and financial risks from noncompliance: Noncompliance has reputational risks and can be costly, with potentially cumulative procedural fines ranging from 1% for minor infringements to up to 10% of the undertaking's aggregate turnover. This is without accounting for potential divestments, mandatory access to assets or, at least in theory, the dissolution of the transaction.

d. Implications for risk allocation in deals: The proposed rules may lead to negotiations on new disclosures and warranties, conditions precedent and longstop timing clauses in M&A agreements, dealing with the allocation of risk under the new review system.

e. Timing considerations may also be critical: In some cases, the time and effort needed to prepare notifications and the risk of lengthy regulatory reviews—even more so in the case of an in-depth investigation—could discourage buyers and sellers in M&A transactions, disadvantage foreign bidders in case of close bids in a bidding war, and effectively exclude foreign entities from participating in public procurement tenders where timing is of the essence.

f. Significant legal uncertainty: The Regulation borrows from a number of existing EU instruments as well as WTO rules. For example, it is expected that EU State aid law might be used as a road map to determine when a foreign subsidy may be considered to be distorting the EU internal market. Similarly, the process for the review of concentrations, including the rules to calculate turnover, builds on EU merger control rules, and both the investigations and public procurement tools contain elements that are familiar from trade-related countervailing duty investigations.

An example of how the interaction between EU State aid law and the Regulation might play out in practice is provided by tax arrangements/rulings. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) recently found, in its seminal Fiat decision (joined cases C-885/19 P and C-898/19 P) that, should a state decide to incorporate the arm's-length principle in its national tax law, then there is generally no basis for a finding of State aid, provided that this does not lead to a systematic undervaluation of the transfer prices applicable to integrated companies or to certain of them. By analogy, we would expect that tax arrangements complying with the principles set out by the ECJ in this judgment are unlikely to be considered distortive foreign subsidies. That said, until the first cases are adjudicated by the EU courts, considerable uncertainty will remain as to how and to what extent existing EU instruments might interact with this Regulation.

g. Relationship to other international agreements regulating subsidies: Besides WTO rules (discussed above), the European Union has already entered into international agreements with non-EU countries that contain specific provisions on subsidies/State aid. Those treaties include criteria for possible approval of subsidies as well as procedural and enforcement details. To cite a few examples, the European Union has signed such agreements with:

- Japan (Chapters 12 and 21 of the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement);

- New Zealand (Chapter 10 of the EU-New Zealand Free Trade Agreement);

- Tunisia (Article 36(2) of the Euro-Mediterranean Agreement);

- Ukraine (Section 2 of Chapter 10 of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement);

- Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway (Part IV and Article 62 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area); and

- Various Balkan countries (corresponding stabilization and association agreements).

Accordingly, Article 44(9) of the Regulation prohibits any measure or investigation that would be contrary to the European Union's obligations stemming from international agreements. In light of this, it will be necessary to assess on a case-by-case basis, by examining the specific provisions of each international agreement, whether the agreement in question includes specific substantive criteria and procedural steps for the control of subsidies, thereby potentially precluding the application of the Regulation. This would be especially true if the agreement in question expressly prohibits the European Union from regulating subsidies unilaterally. Be that as it may, it remains to be seen how the EC concretely interprets this exception.

h. Guidelines, implementing regulations and delegated acts: Recognizing the need for additional guidance, the Regulation provides that, at the latest, three years after the entry into force of the Regulation, the EC will publish additional guidelines on (i) the application of the criteria for determining the existence of a distortion, (ii) the balancing of the distortive effects of a foreign subsidy in the internal market against any positive effects of the foreign subsidy, (iii) the EC's power to request the prior notification of non-notifiable transactions and (iv) the assessment of a distortion in public procurement procedures. These guidelines will be published after consultations with stakeholders and EU Member States and will be regularly updated after publication.

In addition, the EC committed to providing initial clarifications on points (i), (ii) and (iv) above at the latest 12 months after the date of application of these provisions. The EC is also expected to publish a draft implementing regulation for public consultation this month and adopt the final version in the second quarter of 2023. Furthermore, the EC is empowered to adopt delegated acts for the purposes of modifying, by up to 20% if necessary, the notification thresholds or reducing the timeline for preliminary reviews and in-depth investigations.

i. Additional red tape: Finally, the proposed Regulation adds to the bureaucratic burden faced by companies investing or doing business in the European Union. As noted above, in M&A transactions, this comes on top of (i) an existing merger control filing at the EU or EU Member State level, and (ii) a foreign investment filing at the EU Member State level, where this is required. More paperwork, procedures and standstill obligations will have to be handled at the same time.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.