Part 1. Introduction

Technology has the potential to enable more people to be cared for in their own homes by supporting them in managing their own care needs more effectively. It also provides health and social care professionals with information that can help them understand changes in the patient's condition and when intervention might be needed. Telecare and telehealth were highlighted as technology-based solutions in the Deloitte report "Primary Care: Today and tomorrow: Improving general practice by working differently".1 In this report, we explore in more depth the potential for this technology to help the NHS change the way it responds to the growing demand for care.

What are telecare and telehealth?

There is no universal definition of telecare or telehealth, nor is there a single uniform type of technology. Rather, they comprise a wide range of assistive technologies targeted to individual needs. For the purposes of this report, we have adopted the following definitions.

Telecare:

Uses alarms, sensors and other equipment to help people live independently for longer, particularly those who require a combination of social care or health services. Telecare comprises assistive technologies and services tailored to individual needs. It monitors activity changes over time and can call for help in emergencies. For instance, a bed occupancy sensor can monitor when a person gets out of bed at night and raise an alarm if they do not return within a certain period.

Telehealth:

Is aimed at supporting people, typically with long-term health issues, to monitor and manage their own condition. It uses a combination of devices to monitor people in their home and involves the exchange of data between the patient and healthcare professional. The equipment monitors vital signs, such as blood pressure, blood oxygen levels and weight, supporting diagnosis, healthcare management and patient education. The clinician monitors periodic readings to look for trends that could indicate deterioration in the patient's condition. Telehealth solutions can help deliver care tailored to a patient's specific needs that can improve quality of life, prevent avoidable hospital admissions and reduce surgery visits.

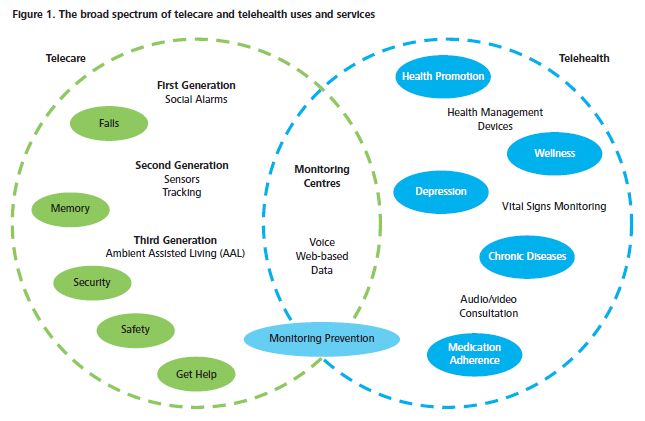

The use of telecare has evolved over decades, predominantly as a social care support tool; telehealth is a more recent development, used largely to monitor the vital signs of people with chronic diseases such as heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and diabetes (Figure 1). The use of telehealth in the UK is accelerating, putting the country at the forefront in Europe. In England, the expansion has been driven by initiatives such as the Department of Health's (Department's) Whole System Demonstrator Programme;2 the 3MillionLives campaign3 and the Concordat between the Department and the telecare and telehealth industry4. There have also been national initiatives in Scotland5, Northern Ireland6 and Wales.7

This report is based on a detailed literature review and discussions with key stakeholders, including primary and secondary healthcare providers, GPs, suppliers, and representative organisations such as the Telecare Services Association. Building on the research conducted for "Primary Care: Today and tomorrow: Improving general practice by working differently",8 the report explores the evidence base for the wider adoption and implementation of telecare and telehealth. It presents a number of examples of evidence-based good practice, illustrating the way such technology is starting to make a difference in supporting more people to have better health outcomes while remaining longer in their own homes.

A brief history of telecare and telehealth

The evolution of telecare started over half a century ago with the development of alarms that initiated a rapid response in an emergency. Such alarm systems traditionally supported people who lived in sheltered housing and dispersed housing situations. Over the past 20 years, the development of new telecare technology has advanced at a pace commensurate with the development of electronic, computing and telecommunication innovations. Today, technology systems support individuals with mobility, sensory or cognitive problems and help improve quality of life for people with long-term conditions, enabling many to maintain a degree of independence for longer.9

The UK Preventative Technology Grant, launched in July 2004, was aimed at encouraging the adoption of telecare and telehealth, and creating an environment in which industry could flourish.10 While the grant helped address some of the social care needs of frail and elderly people, the use of technology to tackle health needs advanced at a much slower pace. Many healthcare providers remain sceptical about the benefits of telehealth and have tended to use it only for specific conditions, such as chronic heart failure.11

Recent developments in mobile technology, particularly the smart phone and the development of mobile applications (apps), have the potential to transform telecare and telehealth. Deloitte predicts that, globally, by the end of 2012, there are likely to be over 500 million smart phones with a retail price of $100 or less, supporting email, instant messaging and a selection of pre-loaded apps. Some 200 million of these phones are likely to have near-field communications capabilities, with potential to transmit patient vital signs and other physiological measurements to healthcare workers at a central site.12 The UK has the biggest app market in Europe13 and by the end of 2012 there will be over 88 mobile subscriptions per 100 individuals and an explosion in tablet computer users.14

Apps are changing fundamentally the way that the public interacts with technology. Across Europe, there are over 40,000 medical, health and fitness apps alone, a volume which can make product choice and navigation difficult.15 These provide information about diseases, medicines and medical devices and can track symptoms and send alerts (known as mHealth). Many apps are aimed at healthcare professionals but increasing numbers are designed for patients. Healthcare providers are watching this development closely, aware that while patient-oriented health apps have the potential to help patients understand and manage their medical conditions better, they can also mislead. Ultimately, they will change the doctor/patient relationship.16 This report focuses on the traditional approach to telecare and telehealth; developments in "mHealth" will be covered in a future report.

Telecare and telehealth can help tackle a number of the challenges facing care providers

The most significant influences on health and social care in the past ten years include:

- more people living longer, accompanied by increasing and complex long-term health problems;

- acceleration of innovative technology; and

- recognition that budgetary pressures across health and social care services require the development of new ways of managing and delivering care that are cost-effective and meet the rising expectations of service users and carers.

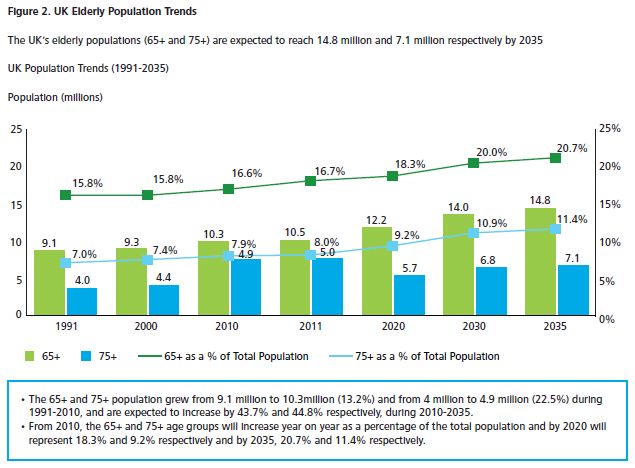

In absolute terms, the UK's elderly population (aged 65+) has risen from 9.1 million in 1991 to 10.5 million in 2011 and is expected to reach 14.8 million by 2035. The population of people aged 75 or over has grown from 4.0 million in 1991 to 5.0 million in 2011 and is expected to reach 7.1 million by 2035 (Figure 2).17

For many people, these extra years of life may be undermined by long-term illnesses that are not curable but need active management rather than episodic treatment. Such care is complex, particularly as many people over the age of 65 have more than one health condition; some have as many as five or six.18 The Department of Health (Department) estimates that up to 75 percent of people above the age of 75 suffer from chronic disease, with the incidence of chronic disease expected to double by 2030.19

Between 1999-2000 and 2010-11, spending on the English NHS increased on average by around 5.5 per cent per year, with similar increases in the other UK countries, in an attempt to raise healthcare spending to the same level as in other developed countries.20 However, the recent economic slowdown has led to the development of austerity plans, with NHS budgets expected to increase by no more than 0.4 percent per year for at least the next five years.21 Given that demand for NHS services is anticipated to continue increasing at around four percent per year, the Department expects the NHS to bridge the gap through efficiency savings and productivity and improvements of around four percent per year, or up to £20 billion by 2015 (the Nicholson Challenge).22 Likewise, local authorities are required to find unprecedented year-on-year savings.23

Meanwhile, an increasing number of people are competing for the services of a decreasing number of carers, with the number of people of working age compared to those who are retired likely to fall from a ratio of 4:1 to only 2.5:1 in much of the developed world within the next 40 years.24 At the same time, the over 65s are placing increasing demands on primary and hospital care services. For example, in England:

- the number of primary care consultations has continued to increase year on year, from an average of 4.2 per person in 2000, to 5.5 in 2008, but with a striking increase in average annual consultations among the over 75s, from 7.9 in 2000 to 12.3 in 2008;25

- across all acute trusts there are year-on-year increases in A&E attendances, which have grown at a rate of 1.2 percent per year for the past four years to 15.9 million in 2010-2011;26 and

- in 2009-10, there were more than 2 million unplanned admissions for people over 65, accounting for 68 percent of hospital emergency bed days and 51,000 acute beds at any one time; the average length of stay for patients under 65 was three days but for over 65s was 9 days.27

These increases in demand illustrate the scale of the challenge facing healthcare providers and the need to change the way this demand is managed. In the remaining sections of this report, we examine: the size and scale of the telecare and telehealth market at a Global, European and UK level (Part 2); the challenges to wider adoption (Part 3); and solutions in the form of case examples where measurable improvements in outcomes have been demonstrated (Part 4).

Part 2. The telecare and telehealth market today and tomorrow

Growth in the telecare and telehealth market - today and tomorrow

The global telecare and telehealth market is forecast to grow to £14.3 billion by 2015, up from £6.2 billion in 2010.28 The European market in particular is growing fast, with governments investing heavily in the infrastructure required to tackle increasing population needs. However, this market is highly fragmented and relatively small, and with social, institutional, economic and technical barriers to overcome, its growth potential is unpredictable. From an industry perspective, there are blurred conceptual and market boundaries; from a provider perspective, there are blurred frontiers between health and social care; and from a user perspective, there are problems distinguishing types of user as well as an overlap between health, social care and wellness.29

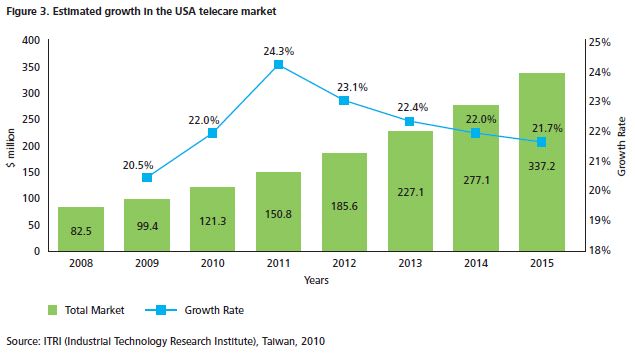

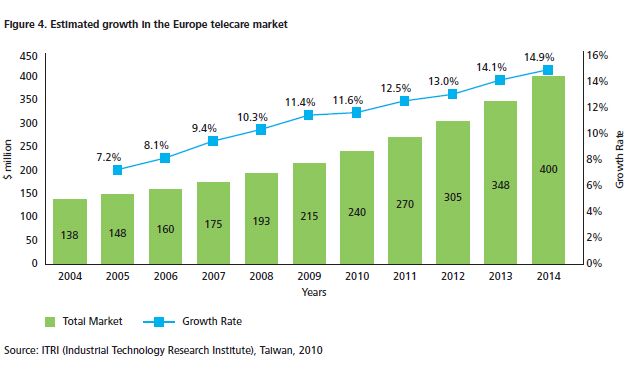

Currently, the telecare market is most mature for firstgeneration telecare (social alarms), which are widely used compared to second-generation equipment like tracking sensors, and third-generation equipment like ambient assisted living devices (see Appendix). Indeed, first generation telecare is mainstreamed in the majority of developed countries, although levels of penetration vary from below one percent to more than 18 percent of over 65s. Second and third generation telecare have yet to be mainstreamed in any country. The UK is arguably a leading nation in this respect with a total estimated annual spend of £106 million in 2010 (compared to £154.8 million in Europe). Projected spend in the UK by 2015 is £251 million (a 12.5 percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR)), compared to £277 million in Europe.30 In 2010, the United States of America (USA) and European telecare markets were considered the most promising for growth (Figures 3 and 4).31

At present, telehealth is much less mainstreamed, with the USA and Japan considered the most advanced. There have been some large-scale trials in Europe and some local trials in other countries. The estimated spend on telehealth in Europe in 2010 was some £148 million, of which £35.7 million was spent in the UK. This spend is expected to increase to £296 million and £70 million respectively by 2015.32

The combined telecare and telehealth market in Europe recorded revenues of approximately £303 million in 2010, and these are expected to rise to £573.5 million by 2015. The combined UK market was £141.7 million in 2010 and is expected to reach £320 million by 2015.33 Overall, the market is expected to grow by 12.2 percent per year (CAGR) from 2010 to 2015, compared with 10 percent between 2006 and 2009. Even with a conservative estimate of future use, the European market for telecare and telehealth equipment is likely to be worth billions of pounds.34

The European market in 2009 was dominated by the UK and Germany with 25 percent and 21 percent market share respectively (Figure 5). Other prominent markets include France, Italy and Benelux (comprising Belgium, Luxemburg and the Netherlands).35

Expansion of the telecare and telehealth market in the UK

In the UK, the telecare and telehealth market is highly fragmented with over 80 players, including over 25 players on the National Telehealth Framework. Tunstall is the dominant player, providing telecare sensors, monitoring software and monitoring centres. Other leading firms include Doboco, O2 Healthcare, Chubb Community Care, Just Checking, Phillips Healthcare, Care Innovation, Bosch, Tynetec, Telesupport and Invicta Telecare.36

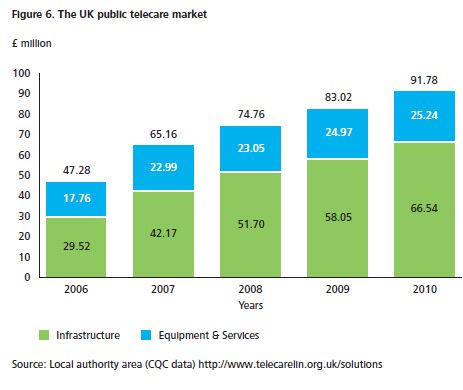

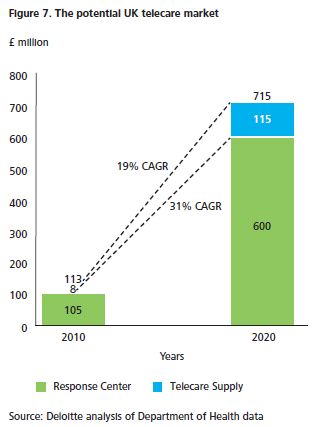

The telecare market in 2010 comprised 90 percent public and 10 percent private spending. There were around 1.6 million users each spending on average around £66 on telecare (including alarm installation and response centres). The highest penetration of telecare was within the over 65 age group.37 According to the UK's local authorities' expenditure reports, the public sector telecare market in England was worth £91.8 million in 2010, with 75 percent of spend on equipment and services (Figure 6). This expenditure has been increasing at a steady rate of 18 percent per annum with the fastest growth seen in equipment and services at 23 percent. Using Department of Health data, we estimate that the total income from telecare in the UK could rise to £7.15 billion by 2020, a growth rate of 19 percent from 2010. The market for private response centres could exceed this growth rate as local authorities move to more outsourcing (Figure 7).

From 2006 to 2010, the telecare user base in the UK increased from 1.3 million to 1.6 million, a CAGR of 5 percent. The penetration level for the population aged over 65 increased from 17 percent to 19 percent.38

The Whole System Demonstrator Programme The Whole System Demonstrator (WSD) Programme, launched by the Department of Health in 2008, is Europe's largest randomised control trial of telecare and telehealth services. Interim results, published in December 2011, showed that telehealth services appeared to reduce mortality, increase speed of clinical care delivery, reduce the need for hospital admissions, lower the number of bed days spent in hospital and reduce costs to the NHS.39 In June 2012, the British Medical Journal published an independent review of the WSD programme,40 led by researchers at the Nuffield Trust and leading healthcare academics (Case example 1). The Nuffield Trust published separate research which reiterated the interim findings but urged caution, because of uncertainty over costs.41

Case example 1. The impact of telehealth on use of secondary care and mortality - results from the Whole System Demonstrator trial (June 2012) 42

Background In 2008, a new randomised control trial was launched, providing telehealth services to some 3,100 patients in three parts of England (with a further 3,000 in the control group). The participants had been diagnosed with COPD, heart failure or diabetes. Recruitment of these patients and installation of equipment took 17 months, after which the trial was monitored for 12 months.

Results The results showed that telehealth delivered significant reductions in mortality (a 45 percent difference in mortality); reduced emergency admissions by 20 percent; led to 14 percent fewer elective admissions and 14 percent fewer bed days. Differences in hospital use were most marked at the start of the trial when there was a distinct rise in admissions of the control group (which arguably could have been due to increased awareness by patients and/or clinicians). The overall costs of hospital care were £1,888 less than those for the control patients (which was not statistically significant).

Launch of the 3millionlives campaign

In January 2012, the Department launched a campaign to use telecare and telehealth technology, aimed at improving the lives of three million people over the next five years - the "3millionlives campaign." The Department estimated that at least three million people with long-term conditions and social care needs could benefit from the use of such services. Paul Burstow, the former Minister for Care Services, announced a Concordat between the Department and the UK telecare and telehealth industry, aimed at demonstrating the intent of both sides to work together over the next five years to accelerate the use of technology under the banner of 3millionlives.43

The main objectives for the 3millionlives campaign are:

- to work together over the next 5 years to develop the market and remove barriers to delivery;

- to create the right environment to support the uptake of telecare and telehealth, including rewarding organisations for adopting and integrating these technologies; and

- for industry to work with the NHS, social care and other stakeholders to simplify procurement and commissioning processes for telecare and telehealth services at scale.44

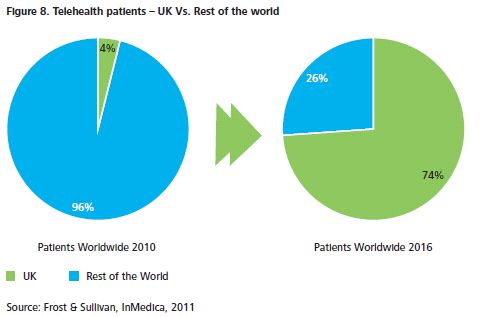

The campaign is expected to extend the reach of telecare and telehealth, and improve the lives of many people through integrating services. Implemented effectively, it is expected to "alleviate pressure on long-term NHS costs and have a profound impact on the world telehealth market, catapulting the UK into pole position". Should the 3millionlives campaign be implemented in full, estimates suggest that by 2016 the UK might account for 74 percent of worldwide telehealth patient numbers, up from 4 percent in 2010 (Figure 8).45

In November 2012, the Secretary of State for Health launched the first NHS Mandate structured around five key areas where the government expects the NHS Commissioning Board to make improvements:

1. Preventing people from dying prematurely.

2. Enhancing quality of life for people with long-term conditions.

3. Helping people to recover from episodes of ill health or following injury.

4. Ensuring that people have a positive experience of care.

5. Treating and caring for people in a safe environment and protecting them from avoidable harm.

Included in the Mandate is an objective to achieve a significant increase in the use of technology, with specific reference to telecare and telehealth. Although no specific targets are set, it states that by March 2015, "significant progress will be made towards 3 million people being able to benefit from telehealth and telecare by 2017; supporting them to manage and monitor their condition at home and reducing the need for avoidable visits to their GP practice and hospital."46 The continued support for the technology has been welcomed by the industry group which acknowledges its key role in "helping to make the doctor's life easier whether by system integration or care pathway redesign or via patient engagement and evidence of outcomes".47

Strategies for the wider adoption of telehealth vary by country in the UK

The four nations of the UK have taken different strategic approaches to promoting the wider adoption of telehealth. In England, the WSD programme, 3millionlives campaign, Delivering Assisted Living Lifestyles at Scale (DALLAS) and the NHS Mandate demonstrate the positive support at the national level for the wider-scale adoption of assisted technology. However, the delivery of these ambitions rests with the new Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) in partnership with local authority Health and Wellbeing Boards. CCGs will have responsibility for some £60 billion of healthcare expenditure and they are expected to be well placed to commission services that best meet these needs.

With over 212 CCGs and clinicians' concerns about the perceived lack of robust evidence on cost-effectiveness of telehealth, industry will need to develop new networks, relationships and metrics to demonstrate the benefits of the wider adoption of the technology.

The Scottish Government has arguably been at the forefront of telehealth for a number of years. The Scottish Centre for Telehealth was set up in 2006 and became part of NHS 24 in 2009. In April 2010, it was renamed the Scottish Centre for Telecare and Telehealth (SCTT), with a remit to implement five major national projects and create a set of standards for telehealth use aimed at supporting the development of strategic long-term solutions. The SCTT considers there to be a very strong evidence base for the adoption of telehealth solutions as a means of reducing unscheduled care and improving access to NHS services.48

In Wales, there have been three demonstrator projects testing new ways of managing chronic conditions, including the use of predictive risk software (PRISM) and telehealth. In 2009-10, reported savings were over £2.2 million. The Chronic Conditions Management Demonstrator sites in 2010-11 showed improved patient care, reduced emergency admissions and NHS savings. Other projects include the introduction of a virtual clinic, which involved consultants visiting GPs to review referrals and the trialling of an email consultation service. The second-year report showed that between 2008 and 2009 there had been a fall in bed days of between 16.5 and 27 per cent and a 10.8 percent reduction in emergency medical admissions which NHS Wales estimate saved £2.4 million.49

Northern Ireland has adopted the largest mainstreamed telehealth service procurement in the UK, involving an £18 million remote tele-monitoring contract awarded in 2011 to TF3 (a consortium of Tunstall, FoldHousing and S3). This was intended to support 6,000 patients with diabetes, stroke, heart and respiratory conditions over 6 years, by testing pulse, blood pressure and body weight on a daily basis. It is expected to lead to a better patient experience and outcomes as a result of earlier interventions and reducing exacerbation in people's conditions.50

Other initiatives aimed at helping to improve use of assisted-living technology

In 2011, the Technology Strategy Board announced a competition to identify 4-5 sites to run a £37 million pilot, DALLAS, running in parallel to the 3millionlives campaign. Four communities (projects) to run over 2 years were announced in May 2012. They cover long-term conditions and the wider wellness, health and wellbeing agenda. A key requirement was interoperability in the information flows between the different systems. The aim is to unlock new markets in social innovation, service innovation and wellness, enabled by technology, and show that technologies and services can be made available at a sufficient scale and cost to enable independent living. The intention is to help expand the sector and position UK companies to take advantage of increasing global demand for assisted living goods and services.51

Nationally, there remains significant scope to expand the use of and improve equity of access to telecare. In September 2012, the Good Governance Institute published a report on an audit of telecare use in England. This showed significant variations in the number of people using telecare services across local authority areas. For example, one reported that over 12,000 people were using telecare services while another reported only 75 users. There was also a mixed understanding among local authority commissioners of what telecare services are and how they should be incorporated into the council's social care services. Although research suggests that some 1.6 million people are using telecare, the figures reported by councils accounted for a fraction of this. Furthermore, only £28 million (4%) of the additional £648 million allocated to local authorities by the NHS to support social care services in 2011-12 went towards funding telecare services.52

Footnotes

1 Primary care: Today and tomorrow - Improving general practice by working differently. Deloitte Centre for Health Solutions, May 2012. Available at: www.deloitte.co.uk/centreforhealthsolutions

2 In 2006, the Department commissioned three large pilots of telehealth which became known as the Whole System Demonstrator Programme. The first headline findings were published in December 2011: Department of Health, 5 December, 2011. Available at: www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_131689.pdf

3 See: www.dh.gov.uk/health/2012/01/roll-out-of-telehealth-and-telecare-to-benefit-three-million-lives . January, 2012.

4 A concordat between the Department of Health and the telehealth and telecare industry, Department of Health, 19 January, 2012. Available at: www.dh.gov.uk/health/2012/01/roll-out-of-telehealth-and-telecare-to-benefit-three-million-lives

5 Scottish Centre for Telehealth and Telecare and NHS 24 strategy. Available at: www.nhs.nhs24.com

6 Remote telemonitoring contract. http://www.northernireland.gov.uk/index/media-centre/news-departments/news-dhssps/news-dhssps-231202-transformation-of-health.htm 7 Chronic Conditions Management Demonstrator sites and Telecare Monitoring Centre Consolidation.

8 Primary care: Today and tomorrow - Improving general practice by working differently. Deloitte Centre for Health Solutions, May 2012. Available at: www.deloitte.co.uk/centreforhealthsolutions

9 Telecare, Telehealth and assistive technologies, Centre for Usable Home Technologies (CUHTec), 2007.

10 Building Telecare in England, Department of Health, 2005.

11 Perspectives on telehealth and telecare: Learning from the 12 Whole System Demonstrator Action Network sites, The King's Fund, 2011. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/articles/perspectives-telehealth-and-telecare

12 Deloitte DTTL, Technology Media and Telecommunications Predictions 2012.

13 See: www.research2guidance.com/news-uk-app-market-size-will-reach-556-mio.-euro-by-the-end-of-2012/

14 ibid.

15 Foreword of first edition of the European Directory of Health Apps (2012-2013), September, 2012. Available at: www.patient-view.com

16 ibid.

17 National Population Projections," Office of National Statistics, UK, 2010.

18 The Future of General Practice, The role of primary care in the new NHS, Haslam D, 25 May 2005. Available at: www.psmg.info/images/event27_2.pdf

19 Ageing population and long term conditions fact sheet, Department of Health, 2010. Available at: www.dh.gov.uk/en/Healthcare/Longtermconditions/DH_064569

20 National Health Service Landscape Review, Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General, HC 708 Session 2010-11, National Audit Office, 20 January 2011. Available at: www.nao.org.uk/publications/1011/nhs_landscape_review.aspx

21 Spending Review 2010, HM Treasury, 22 November 2010. Available at: www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/spend_index.htm See also: www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-11569160

22 The Operating Framework for the NHS in England 2011/12, Department of Health, 15 December 2010. Available at: www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_122738

23 Perspectives on telehealth and telecare: Learning from the 12 Whole System Demonstrator Action Network sites, The King's Fund, 2011. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/articles/perspectives-telehealth-and-telecare

24 Telecare, Telehealth and assistive technologies, Centre for Usable Home Technologies (CUHTec), Journal of Assistive Technologies, 2007. Available at: www.telecareaware.com/otherpages/jat1-2debate_article.pdf

25 NHS Information Centre Q Research Consultation Rates, 2009.

26 Office of National Statistics and Hospital Episode Statistics on Accident and Emergency Attendances 2010-11.

27 Older people and emergency bed use: exploring variation, The King's Fund, August 2012.

28 Healthcare Equipment & Supplies Healthcare Report," Clearwater, IMAP, 2011.

29 Strategic Intelligence Monitor on Personal Health Systems phase 2 (SIMPHS 2) Market developments - Remote Patient Monitoring and Treatment, Telecare, Fitness/Wellness & mHealth: Author: Peter Baum, Fabienne Abadie (JRC IPTS) Editors: F. Abadie, M. Lluch, F. Lupiañez, I. Maghiros, E. Villalba, B.Zamora (JRC IPTS)- European Communities, 2012.

30 ITRI (Industrial Tehnology Research Institute) Taiwan, 2010.

31 ITRI (Industrial Technology Research Institute), Taiwan, 2010.

32 Strategic Intelligence Monitor on Personal Health Systems phase 2 (SIMPHS 2) Market developments - Remote Patient Monitoring and Treatment, Telecare, Fitness/Wellness & mHealth: Author: Peter Baum, Fabienne Abadie (JRC IPTS) Editors: F. Abadie, M. Lluch, F. Lupiañez, I. Maghiros, E. Villalba, B.Zamora (JRC IPTS) - European Communities, 2012.

33 Remote Patient Monitoring Market in Europe Witnessing a High Growth Trajectory, Frost & Sullivan, 2010.

34 European Union 2010.

35 Remote Patient Monitoring Market in Europe Witnessing a High Growth Trajectory," Frost & Sullivan, 2010.

36 http://gps.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/suppliers

37 Deloitte analysis of Department of healthdata.

38 ibid.

39 Whole system demonstrator headline findings - December 2011, Department of Health, 5 December 2011 available at www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalasssets/documents/digitalassets/dh_131689.pdf

40 Effect of Telehealth on use of secondary care and mortality: findings from the Whole System Demonstrator cluster randomised control trial BMJ 2012;344:e3874 doi:10.1136/bmj.e3874 (Published 21 June 2012).

41 Nuffield Trust: The impact of Telehealth on use of hospital care and mortality: a summary of first findings from the Whole System Demonstrator trial www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/wsd-2012 (Published June 2012).

42 ibid.

43 A concordat between the Department of Health and the Telehealth and Telecare industry; Department of Health January 2012 Gateway reference 17136. www.3millionlives.co.uk/about-3ml

44 "3millionlives" - Telecare Services Association, UK, 2012.

45 www.informationweek.com/healthcare/mobile-wireless/telehealth-market-to-hit-628-billion-by/231601670)

46 The mandate: A mandate from the Government to the NHS Commissioning Board April 2013 - March 2015 www.wp.dh.gov.uk/publications/files/2012/11/mandate.pdf

47 Press release 14 November by Simon Arnold, UK Managing Director of Tunstall Healthcare.

48 The NHS 24 Strategy and Delivering and Moving Forward the NHS 24 Strategic Framework - www.nhs24.com

49 Wales Chronic Condition Management Initiative and Telecare Monitoring centre Consolidation project. http://wales.gov.uk/docs/dhss/publications/120116final.pdf

50 Northern Ireland European Centre for Connected Health. http://www.northernireland.gov.uk/index/media-centre/newsdepartments/news-dhssps/news-dhssps-231202-transformation-of-health.htm

51 Delivering Assisted Technology at Scale - Technology Strategy Board 2012 www.innovateuk.org/ourstrategy/innovationplatforms/assistedliving/dallas-delivering-assisted-living.ashx

52 Summary briefing of core and support at home: An audit of telecore services in England. September 2012; Available at: www.good-governance.org.uk/Downloads/5846-WEB%20GGI%20Summary%20Briefing%20Telecare%20Audit.pdf

To view this article in full together with its remaining footnotes please click here.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.