Introduction

It is with great pleasure that Deloitte presents this first publication with insight into the real estate management of a number of large cities in Europe. By means of this publication, we hope to make a contribution to the professionalisation of real estate management in the public sector, and the municipalities in particular.

Municipalities have a considerable volume and range of different properties. Typically, their leased or owned portfolios include one or more of the following types of properties:

- Town hall

- Theatres

- Social-cultural facilities

- Museums

- Swimming pools

- Sports facilities

- Fire stations

- Schools

- Social housing units

- Etc.

Consequently, within the municipal boundaries, municipalities are frequently the largest real estate owners and managers. You might expect that such an extensive asset pool would be professionally managed. However, in reality, the experience of our consultancy practices is that in many municipalities real estate management is still in its infancy; and the degree of professionalism and efficiency varies significantly from country to country. In the current economic situation, strategic real estate management definitely offers a good opportunity to contribute to the realisation of savings. In contrast to several other measures being considered, measures related to municipal properties often do not impact the municipality residents and citizens in a significant way. From an administrative and political perspective, it is therefore an interesting theme.

For this reason, we conducted a survey of the current position of real estate management in a number of large European cities. In doing so, we made use of public sources, supplemented by interviews with representatives of the municipalities concerned. The analysis and interpretation of data have been compiled by Deloitte. In practice, it proved challenging to gather relevant portfolio data; partly because public access to such information is sometimes restricted, but mainly because this information is simply not available or scarcely available within municipalities. This is both a striking and alarming conclusion. Without an up-to-date and complete overview of a municipality's real estate portfolio, it is impossible to manage it professionally and efficiently.

The lack of a complete overview of the real estate portfolio is primarily due to the fact that, in the majority of municipalities, the management of properties is still extremely fragmented. In several municipalities, there are at least five departments which are, to a greater or lesser degree, involved in real estate management. In such circumstances, maintaining an effective and permanently up to date overview is an almost impossible task, leading to a lack of central steering, ultimate responsibility, planning and control, uniformity in policy and processes, strategic planning, etc.; precisely the elements which give substance to professional and strategic real estate management.

Municipalities which were not in a position to make sufficient information available have not been included in this publication. However, we hope that they will be stimulated to improve their real estate management so that they can participate in future editions.

The preceding conclusions provide convincing evidence that there is considerable potential for improvement. We would, therefore, recommend municipalities to become far more actively involved in the professionalisation of their real estate management. By doing so they could release resources which could then be used for social purposes and other public tasks.

In this publication, we have included a high-level analysis of real estate management in a number of large European cities. This offers an initial view of the scope of their real estate portfolios and will hopefully inspire both these cities and other municipalities to develop their real estate management further. To support this, we have also included the expert views of some of our Deloitte colleagues, who address municipal real estate management from a variety of angles.

Finally, we have included factsheets about the participating cities and countries. These factsheets provide a view of the current real estate situation and, in as much possible, the local context for real estate management.

As stated above, we hope this publication will contribute to the further development and professionalisation of municipal real estate management. It is our intention to carry out this high-level analysis periodically so that it will be possible to track the evolution and progress in municipal real estate management.

We hope that you will find this publication on municipal real estate to be of interest, and that the information presented herein helps you to understand and think over the challenges and opportunities of municipal real estate management. We welcome your ideas and suggestions about the topics we cover.

Public real estate management in European cities

Deloitte carried out a survey of the municipal real estate management of 15 large cities in 9 European countries. The high-level analysis of the data collected from these cities resulted in some interesting findings, the most important of which are set out below.

Public facilities make a city attractive

Areas become more attractive to people when activities are concentrated. Through the housing of public facilities, municipalities play an important role in enhancing the attractiveness of cities. The price of land is a significant thermometer when assessing the attractiveness of a site and, therefore, the urbanisation. Consequently, land prices in cities are higher than in rural areas. The high land prices result in selection: activities which have little benefit from conurbation will start looking for other sites, and the areas that are freed up can then be filled by precisely the activities which will benefit the most. In this way a city is established, often with a Central Business District, a pattern of residential areas, infrastructure and public facilities. Disparities in land prices, between and within cities and between cities and rural areas, are a sign of external influences and, therefore, a reason to develop a government policy. Research1 has shown that the supply of public facilities and employment causes 50% of the fluctuations in the price of land. The executive board of a conurbation that is trying to maximise the land value surplus should realise a package of public facilities which is deemed optimum from a social perspective.

Large real estate portfolios to house public Facilities

Municipalities have extensive real estate portfolios to house public facilities and, therefore, to enhance the attractiveness of cities. The municipalities that participated in this survey have a real estate portfolio of approximately EUR 2.6 billion for each one million residents (valued in accordance with the Dutch Valuation of Immovable Property Act, referred to as the TAX value). Relatively, Luxemburg has the largest portfolio (EUR 5.1 billion per 1 million residents) and Madrid the smallest (EUR 0.8 billion per 1 million residents). None of these figures include social housing. Looking at the participating municipalities' portfolios for the housing of public facilities, it becomes evident that all the participating municipalities house similar types of facilities: education, culture, sport, recreation, care, civil service offices and social housing. The main exceptions are the Dutch and Belgium municipalities which have no social housing in their portfolios and Milan, which has a large commercial real estate portfolio. Very few or no details are available about the quality of the portfolios.

The need to professionalise real estate activities

In general, the organisation of the housing of public facilities has a similar pattern. The various departments which exploit public facilities are responsible for their own housing. In the course of time, these departments (for example schools, cultural or sporting facilities) have built up huge portfolios in the cities which in some cases are valued in excess of a billion euros and are managed by the departments themselves. Visible consequences include:

- there is almost no harmonisation between departments about, for example, vacancy;

- many departments have their own maintenance contracts;

- frequently, there are no rental contracts with third parties;

- relatively, there is a great deal of overdue maintenance.

Real estate is not a principal task for these departments, as a result of which they are often not capable of undertaking real estate management professionally. If the city is to exploit the advantages of scale and the potential of the real estate optimally, the scope and complexity of the portfolios necessitate meticulous harmonisation with other portfolios in the city, as well as professional management and portfolio management.

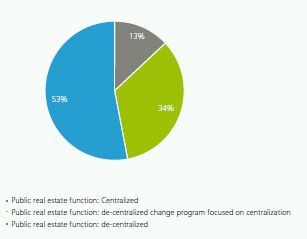

Only two of the participating municipalities (Rotterdam and Münster) have centralised their real estate activities. And it is probably no coincidence that these are both municipalities facing considerable challenges when it comes to creating cities which are more attractive to their residents, entrepreneurs and visitors. Some other cities (Paris, Bordeaux) indicated they were considering centralisation, whereby outsourcing of (part of) the activities would play a role in half of the cases.

Distribution centralisation/decentralisation of real estate in the European cities surveyed

Real estate as a cost-cutting instrument

In the current financial crisis, municipalities are looking carefully at their expenditure and assets. Real estate is an important asset, which should be meticulously analysed. In 60% of the cities surveyed, consideration was given to whether selling off municipal real estate would strengthen the municipality's financial position, but only 20% of the municipalities indicated that steps in respect of selling off real estate had actually been taken.

However, a precondition for this would be that there is insight into the portfolio. Only 25% of the participating municipalities could provide data about the scope, location and value of their real estate portfolios, as the data was either unavailable or spread over numerous departments.

Due to the lack of centralised real estate management in many of the cities surveyed, there is, in general, no question of an unambiguous real estate strategy at city level, nor of explicit policy choices concerning steering parameters for real estate policy. In practice, it would appear that, in several of the municipalities surveyed, an important aspect of portfolio decisions is the influence these will have on the municipality's other policy areas, for example the flywheel function of a municipal office building in spatial development. Steering on the basis of occupancy (demand/supply), quality and sustainability also plays an important role. What was remarkable was that only one municipality (Milan) explicitly steered on the basis of the financial performance of the real estate portfolio.

Number of municipalities indicating they make use of steering parameters in their portfolio management.

Consequently the most important conclusions are

- The cities participating in this survey have a real estate portfolio (excluding social housing) of approximately EUR 2.6 billion (TAX value) for each one million residents. Relatively, Luxemburg has the largest portfolio (EUR 5.1 billion per 1 million residents) and Madrid the smallest (EUR 0.8 billion per 1 million residents).

- The average real estate portfolio consists of in between 2,000 and 3,000 properties (with an estimated GFA of 2–3 million square metres) for each one million residents. As the size of the municipal portfolios is massive, the disposition of superfluous assets is a giant opportunity to realise revenues in times of economic crisis. Only a few cities have made substantial progress in the systematic sale of municipal property.

- In general, all the municipalities provide housing for education, sport, recreation, culture, care and their civil servants. A few municipalities also have a commercial real estate portfolio. In the Netherlands and Belgium, the municipalities do not own any social housing; municipalities in the other " countries do.

- The strategy and 'rationale' behind portfolio composition differs across Europe. Of the participating cities only Milan uses financial performance as the main driver of its real estate portfolio management. 60% of the cities stated that account was taken of the real estate portfolio when cost cutting was under consideration. Sustainability is, remarkably, not a strategic priority for municipal real estate management.

- Currently only about 25% of major European cities can provide reasonably reliable data on the size and value of their real estate portfolios.

- Outsourcing and centralisation of public real estate management are the main trends across Europe.

- Several European cities are conducting (or have conducted) programmes to professionalise their real estate management function among which Paris, Rotterdam and Bordeaux.

If cities are able to exploit the advantages of scale and the potential of the real estate optimally, it will have great impact on the attractiveness of cities. The executive board of a conurbation that is trying to maximise the land value surplus should realise a package of public facilities which is deemed optimum from a social perspective.

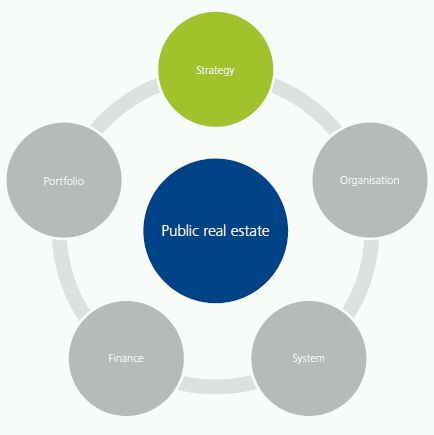

1. Strategy

Steering on the basis of municipal real estate

Having insight in the municipal real estate portfolio is one thing. Steering on that portfolio is the real challenge.

The municipality is responsible for housing civil servants and public facilities such as swimming pools, sport halls, libraries and schools. Consequently , a municipality's real estate portfolio is extensive and the real estate management is complex due to the enormous diversity of the types of real estate and real estate users. Municipalities are faced by a number of questions surrounding the management of these real estate portfolios. Who is the point of contact for real estate? Who is the utiliser of the facilities? How is the rental price which parties renting the real estate have to pay determined? Who is responsible for the maintenance, for investing and divesting (sales, purchases, and developments) and who bears the financial risks? The complexity of the real estate management is even greater whenever sub-municipalities are involved.

In order to manage their real estate portfolios effectively and efficiently, municipalities are increasingly making their organisation more professional. With increasing frequency, municipalities are choosing to have a central body to harmonise the housing of public facilities and to manage the portfolio integrally. A well-known example of this is the municipality of Rotterdam which has established a central real estate organisation so that it is in a better position to steer on the basis of its objectives. Irrespective of the organisational model chosen, an essential part of the question 'how should municipal real estate be managed' is whether and to what extent it is desirable for municipal services and sub-municipalities to be free to steer on the basis of their own real estate, or whether these bodies should be harmonised.

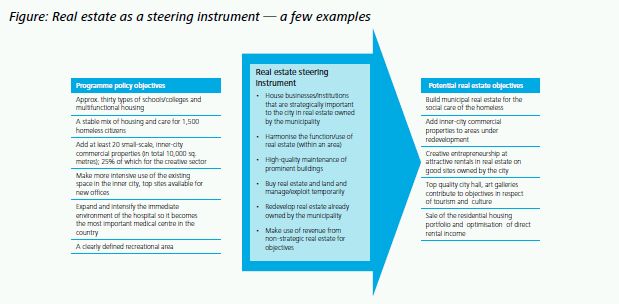

How real estate can contribute to a municipality's objectives

Professional management of a real estate portfolio can contribute to the reduction of vacancy and maintenance costs and to the realisation of agreed quality and sustainability targets. However, in addition to this, real estate can also be used to support municipal objectives. Given the scope of the real estate portfolio and its role in providing housing for facilities, the real estate portfolio is a good steering instrument which can be used to exert influence on the development of a city. To this end, policy objectives need to be converted into a real estate strategy. The figure below illustrates the various ways in which real estate can be used as a steering instrument to help realise policy objectives.

Making use of these steering instruments can affect the divergent interests of a variety of municipal parties and requires clear agreements be made about responsibilities and powers within municipalities.

Preconditions for the optimal use of real estate in municipal objectives

Policy considerations are not always in harmony with real estate considerations. To make optimal use of real estate as a steering instrument in the attainment of policy objectives, a number of agreements must be made. The following paragraphs describe various preconditions for good steering.

Separating those who utilise the facilities from those who exploit the real estate

In order to make good choices in respect of real estate and in respect of facilities, the responsibilities of those exploiting the facilities (the users) and those exploiting the real estate (the owners) should be clearly defined and separated. The two parties have different interests and different expertise. Those exploiting the facilities (for example a swimming pool operator) wish to offer their visitors high-quality facilities for the lowest possible costs; real estate costs are part of a user's operational costs. The user's intention on spending money on real estate is often low. It is easier to please the visitor of the swimming pool with an interesting aqua yoga programm than with systematic preventive maintenance like routine roof inspections. However, the exploiters of the real estate (the owners) have other interests. Their interests and expertise include, for example, the retention of the value of the real estate by means of timely maintenance, the optimal use of the real estate portfolio and, as a result, the reduction of levels of vacancy.

Overview of the real estate portfolio & aligning demand and supply

To make integral choices about housing questions as well as sound investment decisions, it is necessary to gain insight into both the short and the long term requirements of the users in relation to the supply of real estate. It is, however, often virtually impossible to gain this insight as the supply is not managed by one central body with an overview of the real estate portfolio. Through the use of differing definitions (amongst others, the qualitative state of the real estate, the operational costs, the number of square metres), there is a lack of reliable steering information on which to base the best real estate choices.

When demand and supply are aligned, the real estate can be used more intensively and the (normative) vacancy reduced. The example below explains this.

Example: reducing vacancy through multifunctional housing

The municipality is responsible for offering public facilities (sports halls, libraries, care, and education) to different target groups. Facilities are often too expensive to be used by just one target group. In order to make facilities affordable, target groups and facilities are placed together in multifunctional buildings.

Complex development and management:

- Different real estate owners

- Many and different users place a range of requirements on a building

- Users are social parties, frequently without capital " Intensive use of the facilities

Desired situation:

- Professional commissioning on realisation, taking account of the requirements of the different functions

- Focus of the users of the multifunctional building on primary task (not on management)

- Financial optimisation of the development and management of the real estate

- One party for long term maintenance

- Central financing of the building and auditing of the finances

- Affordable and high-quality facilities with the correct combination of functions to attract specific target groups

- Directing the usage: if the composition of a district changes (public) functions may change in the same way.

Insight into financial flows

Insight into the income and expenditure of real estate is essential if good decisions about real estate are to be made. In several municipalities, services and agencies are indirectly subsidised as the rent they pay is below either the cost-effective rent or the market rate. Consequently, there is no insight into the actual expense of the real estate which means the basis for investment decision is lacking. The example below explains this in greater detail.

Example: subsidies on real estate obscure the actual expense of the real estate

The service Sport and Recreation (S&R) of a municipality has purchased property housing, among others, a non-governmental organisation (NGO). The NGO pays a symbolic rent as it cannot afford a cost-effective rent. In such a situation, the difference between the symbolic rent and the cost-effective rent is an indirect subsidy. However, when the municipality's subsidy flow is being considered this amount is not visible. On the other side of the coin, the NGO sees no reason to find alternative accommodation where the rent is cheaper.

Conclusion: Municipal objectives can be supported by the integral steering of real estate

Municipalities have extensive real estate portfolios. The management of real estate portfolios is complex due to the different types of real estate, real estate users, services and the presence of sub-municipalities. For effective and efficient real estate management, whereby real estate is used as a steering instrument to achieve policy objectives, a professional real estate organisation is necessary. A precondition for good control and steering is the separation of the utilisation of the facilities (user's role) and the exploitation of the real estate (the owner's role). Both parties have different interests and different expertise. In addition, aligning demand and supply and, in so doing, integrally managing the portfolio is essential to meet both real estate objectives (such as reducing vacancy or raising the quality level) and policy objectives (such as attracting strategic companies for employment purposes or the improvement of the residential environment in deprived areas).

Lessons learned in structuring the real estate function

Municipalities, like the State, have perhaps never had such scant resources to manage all their assets. How much do their annual maintenance and repair expenses amount to: 5, 10, 50 billion euros? Which buildings have priority? And why: is it enough, too much or too little?

These issues are all the more crucial given that future investments for environmental compliance look to be significant and recurrent. Which indicators can throw some light on how to control and coordinate an asset management policy for a mayor and his executive team?

An awaited professionalization

A municipality must choose between the renovation of a school, a facility management agreement that may reduce the maintenance costs of an administrative centre, the appropriateness of a partnership agreement for public lighting and the restoration of a listed monument (naturally inalienable).

Each municipal authority, often a major real estate owner, cannot ignore the economic value of its assets, insofar as it naturally compensates a debt that has increased considerably in recent years.

But there are still some grey areas. Under-occupancy is poorly understood but may be more widespread than was thought. Certified as "neither complete nor up-to-date", the inventory has to be completed and enriched to become a relevant decision-making tool.

On top of this, the environment very often lacks a sense of responsibility as directorates and their departments have occupied municipal sites for years without really knowing the cost, and sometimes without ever having assessed it.

If there was to be an opportunity for change, it would surely lie in the professionalisation of public real estate management.

The quest for savings, the concern for user Service

To ensure better management, structured real estate directorates are being set up here and there in major French cities. Their work schedule is extensive, and let's hope that it will not become overwhelming: inventory, valuation, geolocation, uses, cost of ownership and performance in terms of public reception are just some of the tasks on the agenda.

Based on a precise and qualified description ("bill of health") of assets which are often very diverse, these new support directorates must come up with ways of reducing operating expenses, and must consider selling or stimulating investment while justifying the expected returns. Municipal asset management can (should?) also generate income: the French State has certainly taken advantage of it, obtaining 400 to 600 million euros from sales depending on the years.

By knowing its assets, valuing them, streamlining its distribution and sharing its needs, under market conditions each municipality may be able to sell its least useful or most costly asset or any surplus. Active management reflexes have yet to be acquired, so as to justify each investment or maintenance expense down to the last euro.

Active management requires a concentration of competencies. What tasks should be performed internally? Which can be outsourced? This concerns not only buildings, but also networks of men and women, agents and users. Optimising real estate management also involves analysing tasks, professions, populations, needs and abilities, and even locations that may inspire groupings, exchanges or other ways of operating or maintaining.

Out of all the expected benefits, the quality of public reception — with, legitimately and quite logically, the quality of working conditions for agents in the background — will profit first and foremost from the overhaul and redeployment of municipal real estate management.

The better the measurement of access quality and service efficiency by municipalities, the stronger their public service mission will become.

Pressure from a state that is now a model?

The legal and regulatory changes opened by state reform are a step in the right direction. The procedures for selling public real estate have been simplified: an obstacle that was once widely criticised has now been removed. Additionally, since municipalities have been required to maintain up-to-date inventories over the past ten years, real estate assets are now at the heart of budgetary concerns because of the new accounting rules.

And political pressure is not expected to ease up. Eric Woerth, the French Minister of the Budget, Public Accounts, the Civil Service and State Reform, believes that the reform of public real estate policy has come to symbolise state modernisation as a whole (including players and local communities). Long-term real estate development plans that were forgotten have again come to life in certain areas. Under the aegis of the new Public Finance General Directorate, a specifically dedicated department looks after the wealth of real estate assets in France. But the task is immense, specifically in terms of "objective" valuations of "owneroccupied" buildings or buildings transferred to establishments.

Despite not always being beyond reproach, the French State has nevertheless paved the way for more rational and more efficient public real estate management. In July 2005, Georges Tron had stigmatised the inadequacies brilliantly in his parliamentary report entitled "State property: break with conservatism." Municipal executives have now understood his message and seem anxious to manage the fate of their real estate: real estate management should no longer be synonymous with conservatism.

2. Portfolio

The building retrofit concept for sustainable public property in Rotterdam

One of the main performance indicators is energy efficiency in existing buildings. The Building Retrofit Concept can help municipalities in realising the desired performance on sustainability.

Rotterdam objectives and the Rotterdam Climate Initiative

The Rotterdam Climate Initiative is part of the international Clinton Climate Initiative (CCI). Over the next few years the Municipality of Rotterdam aspires to become a CO2-free city and a first-class energy port: "The world capital of CO2-free energy"2. This ambition is expressed in the target of a 50% CO2 reduction by 2025, relative to 1990.

One of the main performance indicators is energy efficiency in existing buildings. The real estate portfolio of municipalities is one area where significant energy consumption reductions can be realised. Rotterdam is aware of the options for making the existing real estate energy-efficient, because3:

- Existing buildings cause 50–70% of the co2 emissions in urban areas

- On average existing buildings use 25% more energy than new buildings

- The energy consumption in existing buildings can be reduced by 20–50%

Exploiting these options requires an initial analysis of savings opportunities, followed by taking the appropriate sustainability measures. This will require investments — sometimes considerable. And even though the economic crisis has increasingly made the financing of these investments a bottleneck due to the budget cuts public organisations face, this should not block the opportunities offered by renovating existing real estate.

The Building Retrofit Concept

Countries such as the US, the United Kingdom, France and Germany apply the Building Retrofit Concept to utilise the options for energy savings: this concept can achieve major energy savings through an integral approach with guaranteed results.

The Building Retrofit Concept has two major principles: cost-neutral energy-saving measures and a guaranteed annual energy reduction. The energy consumption reduction is realised through an Energy Service Company (ESCo). The building's owner requests that ESCo submit a plan for energy-saving measures, such as insulating roofs and outer walls and optimising the energy efficiency of equipment and lighting. The ESCo subsequently takes care of the financing, implementation and management of the energy-saving measures.

The energy-saving guarantee and related investments are stated in an energy performance contract. During the agreed contract period the ESCo will be paid a periodic fee based on the annual energy savings effectively achieved. The ESCo will have recovered the investments by the end of the contract period and from that moment onwards the building's owner will benefit from all financial savings.

This gives the Building Retrofit Concept several distinct benefits:

- Integral approach to energy savings opportunities

- Long-term certainty about reduction of energy consumption and CO2 emissions

- No additional investment budgets required

- Improvement in the real estate's quality

- Increase in the building's comfort and interior climate for the user

- Integral outsourcing of management and maintenance duties

- Payment based on performances effectively realised.

Rotterdam Green Buildings: Results of the first Dutch municipal Energy and Maintenance Performance Contract.

The municipality of Rotterdam is implementing the Building Retrofit Concept for its major public real estate through the "Rotterdamse Groene Gebouwen" [Rotterdam Green Buildings]4 programme. The nine municipal swimming pools have been designated as the first pilot project. Rotterdam is the first municipality In the Netherlands to sign an energy and maintenance performance contract. The contract has resulted in the following agreements:

- An average energy cost reduction of 34%, guaranteed and financed by a local contractor (i.e. budget-neutral for the municipality);

- A 15% reduction in maintenance costs over 10 years;

- Increased comfort for swimming pool users and staff by improved control of indoor temperatures and improved water quality (less chloride);

- Professionalisation of the municipal real estate organisation by integrating and outsourcing the maintenance of nine swimming pools in one performance contract for the next 10 years.

CCI and RCI

CCI's mission is to apply a business-oriented approach in the fight against climate change. Stimulating the use of new technologies and finding practical and measurable solutions are pivotal aspects of this approach. CCI collaborates with the C40 Large Cities Climate Leadership Group, an association of 40 large cities around the world dedicated to tackling climate change by developing and implementing a range of actions that will accelerate CO2 emissions reduction.

The Rotterdam Climate Initiative is a collective initiated by the Port of Rotterdam, the City of Rotterdam, employers' organization Deltalinqs and DCMR Environmental Protection Agency Rijnmond. The Rotterdam Climate Initiative creates a movement in which government, organisations, companies, knowledge institutes and citizens collaborate to achieve a fifty per cent CO2 emissions reduction, adapt to climate change, and promote the economy in the Rotterdam region.

Other success stories around the world:

New York, Empire State Building: the Empire State Building is a 2.8 million square feet 1930s landmark hosting retail, office and broadcasting uses. The project, part of CCI's Building Retrofit programme, could reduce the building's energy use by 38 percent and energy bills by $4.4 million a year over the next 15 years. Berlin, extended projects: 25 pools in total with more than 1,300 buildings. Guaranteed total savings: € 10.75 million, approximately 26 %.

Paris: a cluster of a 100 schools will be renovated, with an annual reduction goal of 30%. London: a cluster of 42 municipal buildings (such as offices, police stations and fire stations) has been contracted out, with a 28% agreed annual energy reduction over a period of 7 years.5

To view this article in full please click here.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.