The UCITS IV Directive is set to level the playing field in the European asset management industry. But how will the Directive translate in the world of tax?

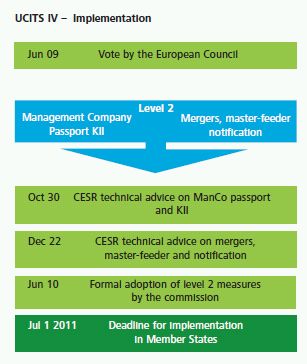

The European Parliament adopted Undertaking for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities (UCITS) IV in January 2009 with the aims of further strengthening the harmonized regime for investment funds, implementing measures to reduce time delays and costs for bringing investment funds to market and more generally making operations and distribution more cost efficient.

The six principal amendments, shown left, will be made to the UCITS regime as part of the Efficiency Package.

However, the Directive does not include amendments in respect of tax. It is recognised that, taken in isolation, the proposals should result in a reduction of the number of management companies, a new wave of fund mergers and master feeder structures as the key avenue into new markets. However, any restructuring of funds or corporate groups to support this will need to be benchmarked against a back drop of disparate tax regimes, each with its own agenda. For many, it is tax which is seen as the key obstacle to UCITS IV making any meaningful impact. This article looks at some of those obstacles and offers some solutions.

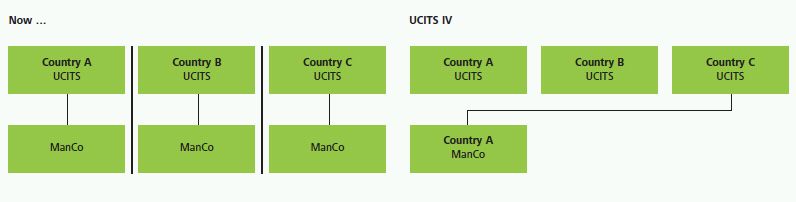

The Management Company Passport (the MCP)

The MCP will allow a UCITS established in one EU Member State to be managed, distributed and administered by a management company, authorized and supervised in another EU Member State. Those services can be provided either through the establishment of a branch or through the free provision of services. The expectation is that, without the requirement to establish a management company in each home EU Member State of their UCITS funds investment management groups will be able to establish operational centers of excellence and minimize duplication of operations, resulting in significant cost savings both from a capital adequacy perspective as well as ongoing overheads perspective. It also provides an opportunity to revisit the tax efficiency of the group structure.

Tax issues for the management company

Investment management groups will need to consider the tax profile of the jurisdiction of choice of the ultimate management company. This will not always be about headline tax rates, but also flexibility around the taxable base. Similarly, restrictions around the deductibility of interest, withholding tax on dividends to shareholders, local CFC legislation and local substance and residence requirements will all be very relevant in any deliberations.

Questions then arise as to how any desired location is to be achieved. Would there be liquidations or mergers of management companies? Is it more like an inversion strategy? Or instead, do the companies remain as is but transfer the investment management contracts between entities? The taxation consequences can be very different.

It is unlikely that a company can simply transfer tax residence without potential exit charges or future tax problems under double tax treaties. Instead, some form of reconstruction may be required although as regards any corporate restructuring within Europe the EU Mergers Directive should provide protection. It will, however, still be necessary to ensure sufficient substance in the ultimate management company.

Alternatively, groups may look to achieve the same economic position by replacing the company party to the investment management contract. If this is the case, it will be important to establish exactly what is happening from a legal perspective. Is the contract being transferred or has the original contract been cancelled and replaced with a new contract and was that envisaged in the terms of the original agreement? Depending on the jurisdictions concerned there may be a taxable disposal which could be classified as an intangible or at the very least subject to considerations as to whether it is revenue or capital in nature.

The impact of VAT distortions will also need to be considered. Whilst VAT, in theory, is subject to EU harmonisation, there are differences not only in tax rates, but also the interpretation of the "management of UCITS" exemption. In practice, therefore, there is often potential to plan around both scope and input recovery depending on the nature of the portfolio content and the management contracts.

Transfer pricing considerations bring both opportunities and potential challenges. Tax authorities are more alert to the subject of transfer pricing, with Ireland being the latest to announce they are introducing legislation. The existence of an overseas management company may raise the sensitivity of this matter with local tax authorities but should not of itself cause major concerns. Currently, the vast majority of investment managers do not provide the full range of their services via the local management company, instead, delegating fund administration, asset management services, distribution activities and even some investment management activities to other entities both within and outside the group.

The tax authorities should continue to approach the issue from the perspective of where the "true value" lies and ensuring that the activities are appropriately rewarded. Nevertheless, within this framework there is potential to transfer price the fee split into relevant jurisdictions to a group's best advantage.

Tax issues for the fund

In addition to the corporate issues, where a UCITS and its management company are located in different EU Member States there are concerns that this could give rise to uncertainty as to the UCITS's tax domicile. Unsurprisingly these tend to be raised by those jurisdictions who are keen not to lose local management companies.

The tax analysis potentially differs depending on whether the fund has a corporate structure or a contractual form. For corporate funds which have their own Board of Directors, there should not be a problem with regards tax domicile of the UCITS, provided the Board performs its role effectively; i.e., making decisions and holding Board meetings in the jurisdiction of the UCITS. However care should be taken as, in practice, it is often the case that the UCITS's Board meeting and the management company Board meeting will take place on the same day, with the same individuals as members. Therefore, it will be necessary for the UCITS to make clear lines of demarcation with regards the meetings of each of the Boards.

For contractual type UCITS, e.g., an FCP, the issue may be more complex. The residence of a Luxembourg FCP is determined by reference to the registered office of its management company and the existence of a foreign management company may alter that residence. This could have consequential knock on as regards the UCITS's liability to tax, VAT rates on services delivered to the fund, EU Savings Directive classification, recognition of tax transparency and the tax regime for investors, as these are all linked to the country of residence of the UCITS.

Fund merger

Fund mergers are nothing new and many groups will have undertaken these recently as they sought to reduce costs over the last 18 months or so.

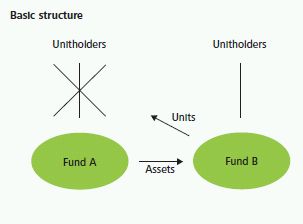

[Essentially, a fund merger is the transfers of assets from Fund A to Fund B in return for the issue of shares in Fund B to holders of Fund A.] Whilst there are often fund mergers within particular jurisdictions, cross border mergers have been less common, often because countries do not have the regulatory framework to accommodate them or there has been legislation actively preventing them.

The UCITS Directive requires EU Member States to allow the three scenarios outlined below, both on a domestic and cross border basis:

- transfer of assets and liabilities to an existing UCITS, merging UCITS dissolved;

- transfer of assets and liabilities to a new UCITS, merging UCITS dissolved; and

- transfer of net assets to an existing/new UCITS, merging UCITS exists until liabilities discharge.

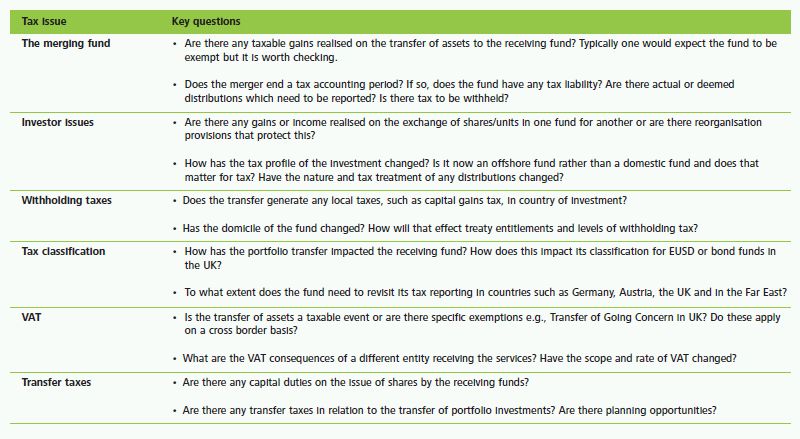

Since one of the key drivers for fund mergers is the reduction of costs, it is important to consider whether there are tax costs associated either directly with the merger or the post merger structure. Whilst the Directive refers to three different mechanisms, the tax implications are broadly the same for each.

Tax issues

Most EU Member States have legislation which enables domestic fund mergers to take place in a tax efficient manner i.e., with no tax cost to the investor or the fund. However, some EU Member States do not extend that relief to cross border mergers.

The Committee of European Securities Regulators (CESR) commented in their December technical release that we may not see cross border mergers because of potential tax adverse consequences and recommends the Commission keeps the issue under review.

As can be seen below left, merging UCITS tax free is not always easy. Whereas tax free domestic mergers are often permitted, that is not always extended to cross border merger. It is true that with careful planning much can be achieved but it is seen by many as "too difficult" and regularly quoted as a reason why the UCITS IV proposal will have limited success in this area.

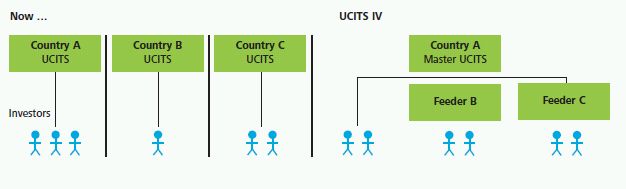

Master feeder structures

Of more immediate attraction may be the proposal to allow master-feeder UCITS structures for the first time. Much of the fund proliferation to date has been to create mirror ranges for particular classes of investor (retail and institutional) or particular markets. The master-feeder proposals will enable fund managers to pool their assets in a single master fund and then distribute that fund strategy to different client segments and target markets, via the feeders. A large master fund should bring economies of scale and as the feeders will hold a small number of investments, (primarily the master fund) there should be reduced additional cost at that level.

A feeder fund can only invest into a single master and must invest more than 85% of its assets into that master; the remainder must be invested in liquid assets. The master fund must be a UCITS fund and cannot itself be a feeder fund or indeed invest via another feeder. Investors into the master fund can either be feeder funds or investors directly. Existing UCITS may become feeder funds.

Tax issues

The application of double tax treaties to collective investment vehicles is already a difficult subject, with individual treaties taking different approaches. Some quite specifically give treaty access to funds, others will grant fund entitlement based on a proportion of the investor base and yet others will demand a full look through basis.

The insertion of yet another level of ownership via the feeder fund can only seek to further complicate this difficult area. Groups will need to consider to what extent a "master-feeder" structure will impact the end investor in terms of withholding tax take. Investors in funds that have typically received treaty relief will be unlikely to agree to investment via a master fund that would not be eligible.

At the other extreme, if funds look to structure to minimise withholding tax they may find that tax authorities have become increasingly alert to possible "treaty shopping". Or is there something we can learn from experience in the area of pension pooling?

The vehicle of choice in that arena is tax transparent with the fund applying withholding tax rates based on the ultimate investor profile. This is dependent on demonstrating that the fund knows the identity of the investor and having systems in place to monitor that. Is it possible that an opaque vehicle could be treated as transparent for tax treaty purposes provided there are appropriate controls in place?

If an existing UCITS fund looks to convert to a feeder fund this will typically require the fund to transfer assets to its master fund in return for shares. In many ways this is similar to a fund merger and the issues to be considered will be those discussed above.

There will also be VAT issue to consider not only on the services and fees flowing between the management company and the funds but also between the master and feeder fund, to the extent there is. Whilst one would hope to rely on the exemption for managing special investment funds, it will be important to ensure that the documentation supports that analysis rather than being an arbitrary allocation of fees between the various entities involved.

Finally the feeder fund will have to be clear how the investment via a master fund impacts the various tax classification we referred to earlier, especially in the context of the various tax reporting regimes around Europe.

Conclusion

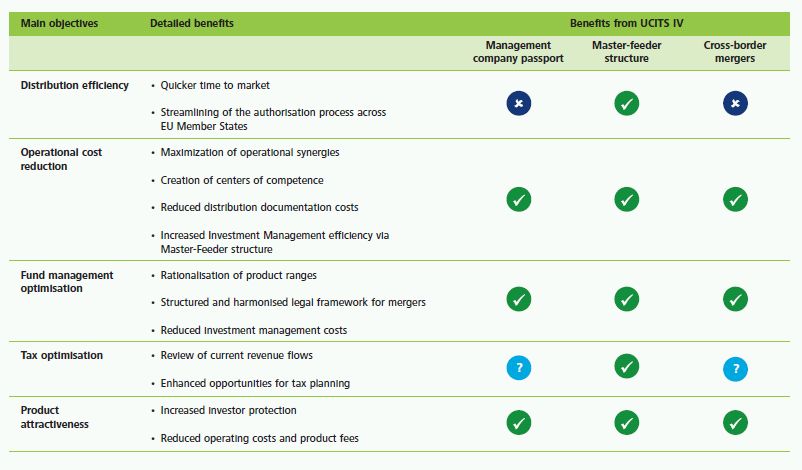

The introduction of UCITS IV should simplify operations and clarify competition in the European asset management industry. It will speed up the time it takes to get products to market, reduce the cost of distribution, encourage the streamlining of product ranges, and help customers compare products across borders (see table below). However, one thing it will not do is simplify tax treatments within the industry. Institutions will have to stay focused on understanding the tax implications as UCITS IV settles into place, and be prepared to respond if they are to enjoy the full benefits of this new directive.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.