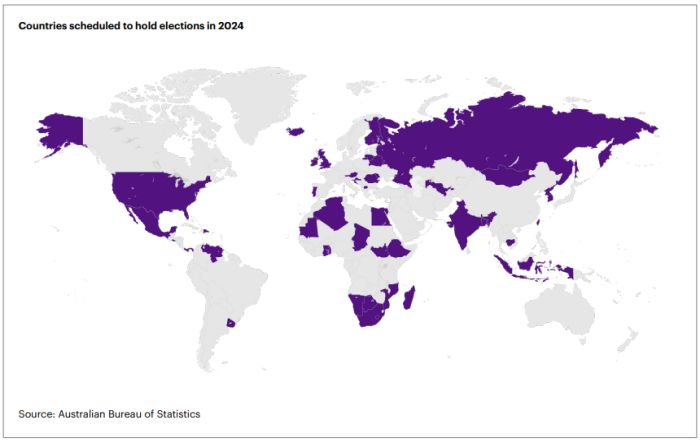

The numbers are striking: according to current estimates, in 2024 there will be 83 national elections in 78 countries. As the U.K. newspaper The Guardian put it: 2024 will be "democracy's Super Bowl." There will not be an equivalent number of elections held worldwide in any single year until 2048.

Of course, such projections should be taken with a grain of salt. It is surprisingly difficult to make an internationallyconsistent count of elections (if elections for the legislative and executive branches are held on the same day, does that count as one election or two? If elections for the European Parliament are held, count that as a single election or one poll for every EU member state?).

Moreover, writing in early 2024, we cannot be certain how many of the elections scheduled for this year will in fact be held. Some of 2024's contests will surely be postponed by budding autocrats. Other polling dates will be unexpectedly added to the annual calendar as parliamentary governments lose no-confidence votes and snap elections are called.

What is clearer is that 2024 is very likely to play host to consequential elections. By some estimates, more than 4 billion votes will be cast in national polls in 2024 (owing in significant part to elections in India and the multinational elections for the European Parliament). That figure may not be reached again until after 2070.

Adding to the drama, it is not likely to be a good year for incumbents. During 2023, inflation rates soared globally and voters frequently punished their leaders at the ballot box. "Economic voting," the tendency of electorates to vote out incumbents who preside over poor economic performance, seemed very much in evidence.

Unlike the Super Bowl, elections are not merely – or even primarily – entertainment. So, what consequences might the 2024 "year of elections" bring? While political events are always unpredictable, there are a few risks to watch as the year unfolds.

Elections that could bring turmoil

The U.S. Central Intelligence Agency's "state failure project," which ran for more than a decade, was an open-source effort to build predictive models of political instability. One of the project's conclusions was that "anocracies" – countries where political power is contested, but not through free and fair elections, are more likely to suffer turmoil than either democracies or dictatorships.

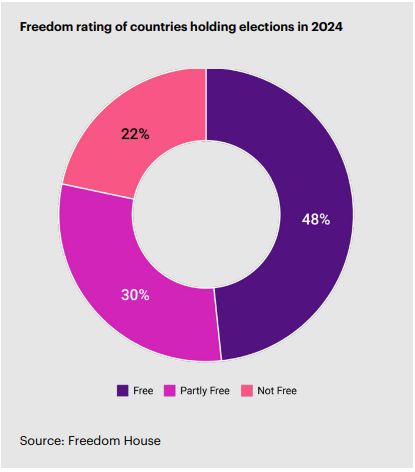

There are quite a few polls coming in 2024 that may fall into that category. These "anocracies" are indeed holding elections – but the votes are unlikely to be free or fair, leaders may have almost unlimited power, and the outcome may well be pre-determined. Opposition candidates may be banned, media reporting may be controlled, or voters may face intimidation. Some of the 26 countries in this category are Belarus, Chad, the DRC, Iran, Russia, Rwanda, Uzbekistan, and Venezuela, which are holding elections but which Freedom House rates as "not free."

Freedom House also has a "partly free" category, which the think tank applies to countries that may have some deficiencies in protection of the rule of law or civil liberties. The vote count may be genuine in these countries, but limits on freedom of assembly, for instance, may hinder opposition campaigns. The 36 countries in this category holding polls in 2024 include Bangladesh, Bhutan, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Tunisia.

While perhaps less likely to descend into outright civil conflict, these "partly free" elections could bring people onto the streets, as governments that are unpopular win re-election through dubious means. Countries currently in the midst of economic crisis, including Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Tunisia, may be particularly vulnerable to such unrest.

Of course, claims that ballots are "rigged" seem alarmingly common these days, even in countries rated as entirely "free" by Freedom House. In Western democracies, populism was a well-established political form in the first half of the 20th century, only to all but vanish after World War II (with a few exceptions, such as Italy's Silvio Berlusconi). In 2016, populism returned to Europe and North America with a vengeance, following the U.K.'s Brexit vote and the U.S. election of Donald Trump.

To view the full article click here

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.