In Short

The Background: There has been a growing trend to invalidate European patents by challenging their formal priority and using intervening prior art. The Technical Boards of Appeal of the European Patent Office ("EPO") referred questions of law to the Enlarged Board of Appeal ("EBA"): first, whether the EPO is competent to assess a party's entitlement to priority; and second, whether a newly added applicant in a Patent Cooperation Treaty ("PCT") application is entitled to claim priority from an application filed by the inventors, if the inventors are designated for the United States only on the PCT request.

The Result: The consolidated decision in G 1/22 and G 2/22 of the EBA addresses a wide range of priority-related issues, including EPO jurisdiction to decide on formal priority, priority entitlement by joint applicants, and general principles governing priority transfer.

Looking Ahead: With the introduction of the concept of an "implied agreement" and a rebuttable presumption of entitlement, the dynamics of priority disputes have been altered, meaning that applicants and patentees will find it less cumbersome to establish their entitlement to claim priority.

Introduction

Attacking the formal priority has become a standard tactic in EPO opposition proceedings nowadays if the applicants of the priority application and the subsequent European application are not identical. According to prior case law, patentees challenged on formal priority entitlement would normally be required to present written evidence demonstrating that the right to claim priority has been successfully transferred from the applicant of the priority application to the applicant of the subsequent European application before the filing date of the latter. If the patentee failed to show such evidence, the priority transfer would likely be considered invalid, rendering the patent susceptible to validity challenge in the presence of any intervening prior art. Under this practice, European patents, including some high-profile patents, were revoked. The most infamous example was the Broad Institute/MIT's recent loss of their foundational CRISPR/Cas9 patents due to a failed priority entitlement, which stemmed from the assignment of the priority right from one of the inventors to a third party.

The consolidated decision in G 1/22 and G 2/22 addresses issues related to formal priority entitlement. The decision arose from a referral by the Technical Boards of Appeal 3.3.04 in two consolidated cases, T 1513/17 and T 2719/19. The referral addressed a common discrepancy, prevalent before the America Invents Act ("AIA"), between the applicants of a U.S. priority application (i.e., inventors) and the subsequent European application (i.e., employer) filed via the PCT route. Central to the case was that the inventors were named as applicants solely for the United States on the PCT request, whereas their employer was named applicant for the rest of the designated PCT states. The EBA was posed with two main questions: first, whether the EPO is competent to assess a party's entitlement to priority; and second, in the aforementioned scenario, whether the newly added applicant in the subsequent application is entitled to claim priority from a priority application filed by the inventors.

EPO's Jurisdiction to Assess Priority Entitlement

The EBA, in its reasoning, draws a clear line between the right to file a European patent application (the lawful title to both the application and the ensuing patent) under Article 60(3) EPC and the right to claim the priority date for that application (the "right of priority") under Article 87(1) EPC). According to established jurisprudence, the EPO is not competent to assess the applicant's entitlement to the patent application. However, this provision does not extend, either directly or analogously, to the right of priority. Given that priority entitlement directly impacts the effective date of the application and, consequently, its substantive patentability, the EPO holds the competency to assess an applicant's entitlement to priority.

According to the EBA, the autonomous law of the EPC governs the priority right and its transfer. As there are no formal requirements for the transfer of priority under the autonomous law, the EPO shall "adapt itself to the lowest standards established under national laws and accept informal or tacit transfers of priority rights under almost any circumstances."

Rebuttable Presumption

The Enlarged Board concludes that the entitlement to priority should, in principle, be presumed to exist for the benefit of the subsequent applicant of the European patent application, provided the applicant claims priority by fulfilling the formal requirements. The presumption, however, is rebuttable to account for the (rare) cases of unjustified priority claims. Thus, in practice, this reverses the burden of proof for priority entitlement. The party challenging the priority entitlement—e.g., the opponent—would now have to provide specific facts that raise serious doubts about the entitlement of the priority claims. It remains to be seen how opponents will tackle the daunting task of proving a negative, especially when the evidence is within the applicant's domain and, subject to certain national discovery proceedings, out of the opponents' reach.

Implied Agreement Between Joint Applicants

The "joint applicants approach" is a long-standing principle at the EPO that applies to the priority right of patent applications. It means that if a patent application is filed by multiple applicants (e.g., A and B), and at least one of them (e.g., A) is also an applicant of an earlier application from which priority is claimed, then the priority right is valid for all the applicants of the later application, unless there is evidence to the contrary.

While there existed a "joint applicants approach" for EP applications, extending it to PCT applications with different applicants for different designated territories has raised some eyebrows. Therefore, the EBA chose not to employ this approach for the PCT application, viewing it merely as a formal bundle of individual patent applications. Instead, the Enlarged Board invoked the idea of an "implied agreement," according to which the act of joint filing is interpreted as an implicit agreement between the parties to share the priority rights. It's vital to note that the concept of "implied agreement" does not apply when some applicants of the priority application are absent in the subsequent application. Essentially, while one can easily add applicants to a PCT/EP application, omitting priority applicants from a PCT/EP application necessitates at least one of the PCT/EP applicants to acquire their priority right before filing.

Practical Advice

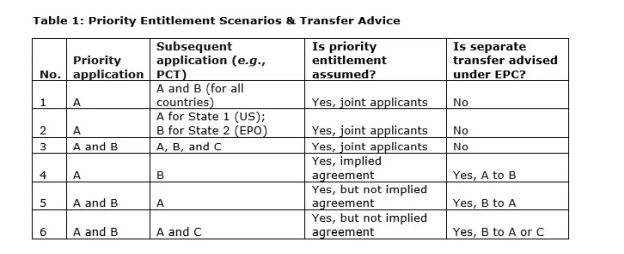

While the rebuttable presumption benefits applicants and patentees, it is vital to recognize the limits of this presumption. The presumption is applicable in all instances where the priority applicant and the subsequent applicant are not identical, irrespective of whether the subsequent application is a PCT application. However, it's not irrefutable. For instance, an agreement cannot be inferred if not all priority applicants are listed as co-applicants for the subsequent application, even though the presumption of priority entitlement remains. In such cases, any absent priority applicant might have a claim on the title of the subsequent application or, at the very least, could challenge the priority entitlement with sufficient evidence. Also, the EBA decision only addresses the question of priority. An almost inevitable corollary from a legal perspective, however, is entitlement to the invention at hand by the PCT applicant(s), which is required in most if not all jurisdictions to have standing to sue. Therefore, we still advocate for a separate transfer in these scenarios as the best practice to preclude future disputes (see Table 1, No. 4-6). On a separate note, it awaits determination how the EU Unified Patent Court ("UPC") or national courts will rule on this matter.

Three Key Takeaways

- With the introduction of the rebuttable presumption, the dynamics of priority entitlement have been altered. Now, applicants and patentees will find it less cumbersome to establish their entitlement to claim priority. Conversely, opponents in EPO opposition proceedings, and potentially at the UPC, will face challenges to prove the invalidity of priority entitlement. This is particularly pertinent to pre-AIA cases where the initial priority application is filed in the inventors' names, but the subsequent application claiming priority is filed under their employer's name.

- Although this presumption is favorable for patentees as it shifts the burden of proof, one should be conscious that it is "rebuttable." This implies that under certain circumstances, especially when there is potential evidence of bad faith or other contentious issues, the presumed validity of the priority claim can still be challenged during opposition proceedings before the EPO or even before the UPC or in national courts.

- Securing written assignments of priority rights before embarking on a PCT application remains a cornerstone of best practice. Such documentation offers a robust safeguard against potential challenges and documents entitlement to the invention. Should compelling evidence arise that questions the validity of a priority claim, these written assignments serve as a critical line of defense, warding off risks associated with potential patent revocations, while at the same time providing the legal footing for any enforcement claims.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.