Co-authored by Denver Bandstra

The screen of your smartphone serves as a marketplace for countless merchants and service providers. Through mobile apps, those merchants and service providers get you from place to place, monitor your health, and assist you in countless other ways every day. If you are a developer of one of those apps, you will appreciate the hard work and effort that goes into producing a unique and usable interface. You will also want to protect yourself against knockoffs and imitators with intellectual property protection.

One common form of intellectual property protection sought for mobile apps and software generally is the "utility patent," more commonly simply called a "patent." A utility patent is sometimes referred to as the "Cadillac" of intellectual property; it can confer unparalleled status to the owner when compared to other forms of IP. Like its automotive counterpart, however, a utility patent can be expensive to obtain. In addition, the eligibility of software-based inventions for utility patents has been a topic of considerable debate in recent years. Courts in the United States and elsewhere have attempted to establish rules (e.g. Mayo and Alice) for when software-based inventions are eligible for patent protection. These rules can be difficult to parse, and often require the assistance of a professional to decide whether it will be possible to obtain a utility patent. Finally, a utility patent requires the owner to publicly disclose the inner workings of their invention, and to eventually make it freely available for use when the patent expires.

If the prospect or cost of a utility patent seems daunting, then software innovators should consider alternative forms of IP protection and, in particular, industrial design (design patent) protection. For many mobile app and software developers, industrial designs may be an ideal form of intellectual property. Moreover, industrial designs are typically less expensive than utility patents, do not require the detailed disclosure of a utility patent, and do not involve the same eligibility considerations as a utility patent.

In Canada, an industrial design is defined as a feature of shape, configuration, pattern or ornamentation and any combination of those features that, in a finished article, appeals to and is judged solely by the eye.1 In the United States, design patents are similarly available for any new, original, and ornamental design for an article of manufacture.2

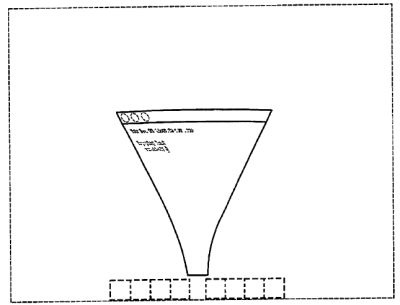

Traditionally, design protection has been used for finished articles, such as glassware, athletic shoes, or audio speakers. However, design protection is also available for electronic ornamentation, which includes the graphical user interfaces (GUIs) found in software, and the elements used to form them. Technically, such designs are granted for a display screen itself, which is the finished article to which the electronic ornamentation – generated by software – is applied. For example, a design for an icon within a phone app may depict the icon within the confines of a phone screen. However, though the drawings must show the relationship between the claimed design and the finished article, the screen itself need not be claimed as part of the design. Typically, dashed or stippled lines are used to indicate that the screen is not claimed as part of the design.

While design protection traditionally has been limited by the requirement for static, black and white line drawings to accompany the application, the Canadian Industrial Design Office has recently indicated that it will accept applications for animated designs and colour designs. This acceptance of animated and colour designs follows similar practices in the US Patent and Trademark Office and elsewhere.

This development opens up a range of possibilities for protecting software GUIs used in mobile apps, which often feature unique animated elements or colour elements that enhance their appeal. Protecting such seemingly ornamental features could serve as a useful product differentiator on the smartphone screen, and a barrier to competitors, who could be forced to use alternative design elements that may not be as recognizable or appealing to consumers.

For example, Apple has famously used design patents to protect aspects of its iPhone and Mac user interfaces. In 2009, Apple obtained a U.S. design patent for a "display screen" that included colour elements, and which claimed the default arrangement of icons on an iPhone home screen. This design patent was later successfully asserted by Apple against Samsung. Although there were differences between the Apple design patent and Samsung's GUI, a jury found the general colour schemes to be similar and ruled in favour of Apple. Apple is also the owner of a design patent for another widely-recognized animated user interface element: the so-called "genie effect" that appears when minimizing a GUI window.

These seemingly simple examples demonstrate that design protection can be an inexpensive, yet powerful tool to block competitors from copying unique and innovative design elements that distinguish one mobile app from another in the smartphone screen marketplace. When a software-based invention appears to be on the edge of what is eligible subject matter for a utility patent, or when the cost of pursuing a utility patent may be a deterrent, then software developers should consult with an intellectual property professional to review their software user interfaces, and to consider what unique design elements – whether black & white, colour or animated –could serve as the basis for valuable IP protection.

Footnotes

1. Industrial Design Act, RSC 1985, c I-9 s 2.

2. Patent Act, 35 USC § 171.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.