Transfer pricing economists must consider various transfer pricing methodologies when assigning intercompany profits to related parties. Given the difficulty in applying the Comparable Uncontrolled Price ('CUP') and gross margin methods (due to the high level of comparability requirements), the Transactional Net Margin Method ('TNMM'), though considered, until recently, a method of last resort by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ('OECD'), is often employed.1 In my experience, I have witnessed many economists electing to apply a Berry Ratio as a transfer pricing methodology without fully understanding the theory behind such an approach. Nothing seems to elicit a stronger response from taxpayers and tax authorities alike than having the Berry Ratio employed to assign profits to related parties operating in different jurisdictions. The Berry Ratio must be used with caution and based on sound theoretical arguments. Since the Berry Ratio assigns a mark-up solely on Selling, General and Administration ('SG&A') expenses, its application is often contested by those who argue that such an approach assigns too little profit to the parties in question. This article discusses the limited number of cases where the Berry Ratio should be applied, further supporting Dr. Charles Berry's premise that the ratio should be applied as an exception and not as a rule.

l. Berry Ratio defined

The Berry Ratio is defined as the ratio of a company's gross profits over SG&A.2 All too often, practitioners are willing to apply a Berry Ratio because of the ease at which it can be applied, without truly understanding the theory behind the ratio. From a practical perspective, a Berry Ratio should be assigned to test profits of limited risk distributors or pure service providers who utilise no intangible assets when performing their day-to-day operations. In such a scenario, the Berry Ratio can apply if a direct link exists between operating expenses and gross profit.

However, the weaknesses of the Berry Ratio can readily be seen by discussing the comparability factors needed to apply it correctly, as well as by consideration of the fact that the 'simple' entity that needs to exist before the Berry Ratio can apply rarely exists in practice. This is where we turn our attention to next regarding the difficulty with the Berry Ratio.

ll. Functional comparability

Finding comparables that perform the same functions as the tested party becomes critical when applying the Berry Ratio. A failure to do so will result in the wrong level of profits being attributed to the tested party for the services/functions performed (as measured with a mark-up on SG&A to arrive at gross profits). Given that the Berry Ratio calculates the level of profitability by marking up SG&A with a factor determined by a set of comparables, the comparables selected should have a high degree of similarity to the tested party. Selecting comparables in different industries where the impact of SG&A activity on profits may vary will yield different profit levels than those of the tested party's industry. For example, clear comparability issues would arise if pharmaceutical marketing comparables were used when considering an arm's length mark-up for commodity-based distributors. Failure to locate comparables that perform functions of similar value, while facing similar business pressures, could result in a distorted profit level being attributed to the tested party.

Notwithstanding the difficulties of finding comparables with the required high level of functional comparability, the issue of intangibles likely poses the most significant challenge when applying the ratio.

lll. Presence of intangibles

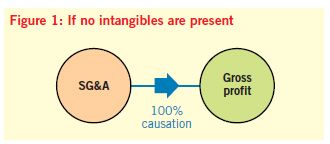

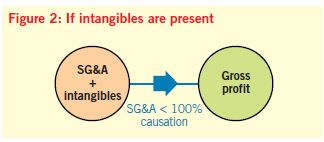

For the Berry Ratio to be applied correctly, a direct link must exist between SG&A and gross profits. A problem with applying the Berry Ratio, apart from the high level functional comparability requirement, is the need to find comparables that have little in the way of intangible assets. Simply put, the Berry Ratio should never be applied when intangibles exist within the business activity of either the tested party or comparables. The reason for this lies in the fact that it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to determine the scope of the impact that SG&A levels have on gross profits when intangibles are present.

Within the normal course of running a business, firms develop and employ intangible assets when competing in an ever changing globalised economy. In such a case, both intangible property and functions impact gross profit margins, which violates the fundamental premise assumed by the Berry Ratio, i.e. that only SG&A (and the mark-up on these costs) determine gross profit margins.

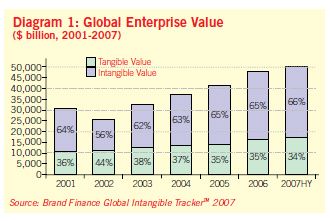

Applying the Berry Ratio requires the tested party to be limited to a stripped down distributor or a pure service provider who pledges little in the way of intangible assets. It has been my experience that very few, if any, tested parties have the limited scope of intangible assets required to apply the Berry Ratio. Intangibles have become increasingly important within the globalised economy, the high value of intangibles to a business operating within this global setting is well documented in literature. As world economies become increasingly globalised, expansion into world markets has put greater emphasis on building and maintaining intangible value such as know-how, trademarks and trade names in order to remain competitive.

According to Brand Finance, an increasing share of enterprise value is made up of intangible assets as illustrated by the graph below. Intangible value increased by approximately 10 percent between 2002 and 2007, while tangible value decreased by 10 percent.

Given the importance that intangibles are assuming in generating value, the Berry Ratio is less likely to provide arm's length profit levels and thus should only be applied in exceptional cases.

lV. Conclusion

The Berry Ratio should be reserved for those cases with limited risk distributors or service providers that employ no intangible assets. For the Berry Ratio to be applied, a direct link must exist between SG&A and gross profit levels. Comparables are often from different industries, and employ some intangibles, which can distort the outcome.

Another complicating factor surrounds the issue of intangibles. The use of intangibles, either by the tested party, the comparables, or both, modifies the impact that SG&A plays in generating profits. The presence of intangibles may have a direct impact on profits or may result in the provision of SG&A activity becoming more efficient. In either event, intangibles will be the main profit driver which contradicts the theory behind the Berry Ratio. Intangible assets are often unique, which makes finding a way to eliminate their impact on profits, and thus making the Berry Ratio more workable, unlikely. Intangible assets are vital to everyday business operations and their presence makes the application of the Berry Ratio unreliable within a transfer pricing setting.

Footnotes

1 The Berry Ratio is considered a TNMM along with the total cost plus, return on asset and operating margins approaches.

2 The IRS defines the cost base when applying the Berry as SG&A plus depreciation. Dr. Charles Berry elected to exclude depreciation given the arbitrative nature in determining depreciation expenses.

Previously published by The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.