There has been a lot of prominence given to prohibition orders ("POs") in recent times, given the unprecedented scale of regulatory action undertaken by the Monetary Authority of Singapore ("MAS") following investigations into the troubled Malaysian owned 1Malaysia Development Bhd. ("1MDB"). This article provides an introduction to the PO regime in Singapore, and discusses how the regime has so far been used by MAS as a means to help ensure the integrity of persons working within the Singapore financial services industry.

As a preliminary point, it should be noted that the PO regime generally applies to both individuals and legal entities. However, this article will focus only on the use of POs against individuals.

Prohibition Orders under Singapore Financial Regulatory Law

Authorising Provisions

The MAS currently has the power to issue POs to prevent unsuitable persons from engaging in activities that are regulated by MAS under the Securities and Futures Act (Chapter 289) ("SFA"), the Financial Advisers Act (Chapter 110) ("FAA"), and the Insurance Act (Chapter 142) ("IA") (but only in the case of insurance intermediaries). In October 2013, MAS had also proposed to amend the Banking Act (Chapter 19) ("BA") to introduce the same regime into the regulatory framework for banking services, but this proposal hasn't yet been implemented. Nonetheless, in practice, most banks in Singapore are also subject to MAS regulation under the SFA and/or the FAA, and as such, many bank staff would already be subject to the existing PO regime under the SFA and/or the FAA.

The PO regime under the SFA, the FAA and the IA are broadly similar. The next few sections of this article will focus primarily on the PO rules under section 101A of the SFA.

Grounds for issuing a PO under the SFA

Until recently, the PO regime has been employed by MAS mainly as an enforcement tool in relation to market misconduct behaviour, such as market manipulation and insider trading. However, in the wake of investigations regarding 1MDB, MAS has also begun to use its power to issue POs in relation to cases involving failure to comply with anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism ("AML/CFT") requirements.

Section 101A(1) of the SFA, in particular sub-sections (c) to (h), describes the grounds on which the MAS may make a PO against a person who is an individual. Broadly, these are as follows:

(i) Where the person's status as a representative has been suspended or revoked;

(ii) Where there exists a legal ground upon which the MAS may revoke the person's status as representative;

(iii) Where the MAS has reason to believe that the person is contravening, is likely to contravene, or has contravened any provision of the SFA, any condition or restriction imposed by MAS under the SFA, or any written direction issued by MAS under the SFA;

(iv) Where the person has been convicted of an offence under SFA, or has been convicted, whether in Singapore or elsewhere, of an offence involving fraud or dishonesty or the conviction for which involved a finding that he acted fraudulently or dishonestly;

(v) Where the person has an order for the payment of a civil penalty made against him by a court, or has entered into an agreement with the MAS to pay a civil penalty, under Part XII of the SFA;

(vi) Where the person has been convicted of an offence involving the contravention of any law or requirement of a foreign country or territory relating to any regulated activity carried out by that person; or

(vii) Where the person has been removed, at the direction of the MAS, from office or employment as an officer of the holder of a capital markets services licence under section 97(1)(h) of the SFA.

In determining whether to issue a PO against a person, the MAS would be guided by considerations as to the person's fitness and propriety. The measure of whether a person is fit and proper is set out in the MAS Guidelines on Fit and Proper Criteria [FSG-G01] (last updated 3 September 2015) ("Fit and Proper Guidelines"), which overlaps to some extent with the statutory criteria, but would involve more specific consideration of the following aspects of a person:

- His honesty, integrity and reputation;

- His competency and capability; and

- His level of financial soundness.

Procedural aspects under the SFA

Procedurally, the MAS is statutorily required under section 101A(4) of the SFA to afford the person an opportunity to be heard before making a PO against him. Thus, the person against whom the MAS intends to issue a PO against would be notified in writing of MAS' intention to do so, and would be afforded an opportunity to make representations to MAS. Such representations would be given due consideration by MAS before a final decision is made as to whether the PO should or should not be issued. In the event that MAS decides to issue a PO against the person, that person will be entitled under section 101A(5) of the SFA to appeal in writing to the Minister in charge of the MAS within 30 days of the MAS decision to issue the PO.

MAS has a practice of publicising the issuance of POs issued under the SFA, FAA and/or IA on the MAS website. Notification of the PO, on the enforcement action page of the MAS website, will remain for a period of 5 years, or until the PO ceases to be in force, whichever is longer.

In relation to individuals who are representatives registered under the SFA and/or FAA, a notation that a PO has been issued would also be indicated against the name of the person within the public register of representatives, and this notation will remain in the register of representatives for the duration of the PO.

PO regime under the FAA

The PO regime under the FAA is almost identical to that under the SFA. The grounds under which the MAS can make prohibition orders against individuals under section 59(1)(ba) to (f) of the FAA are similar to those under the SFA. Section 59(3) of the FAA also requires MAS to afford the person an opportunity to be heard before making a PO against the person, while section 59(4) of the FAA provides for a right of appeal in writing to the Minister in charge of the MAS, within 30 days of MAS' decision.

PO regime under the IA

Under the IA, the PO regime takes a more limited form. The regime is available only in relation to insurance intermediaries, and the PO operates only to prohibit a person from carrying on business as an insurance intermediary or from taking part in the management of an insurance intermediary. The grounds for issuing a PO under section 35V of the IA are also confined to instances where the person is guilty of some form of dishonesty or fraud. Procedurally, the PO regime also provides for a show cause period whereby the person is given the opportunity to be heard before a PO is issued, and once the PO is issued, there is again the right of the person to appeal in writing to the Minister in charge of the MAS within 30 days of MAS' decision.

Forms of the POs

In terms of content, in the case of a PO issued under the SFA or the FAA, MAS has ability to specify sanctions in different forms within the PO. This may include banning the offending person from performing any regulated activity permanently or for a specified period of time, stripping him from his managerial or directorial position (whether direct or indirect), and/or barring him from being a substantial shareholder in the financial institution.

The duration of the PO and the specific sanctions within the PO would generally depend on MAS' assessment of severity and grievousness of the misconduct. Typically, for market misconduct cases, MAS has imposed POs of duration ranging from one year to four years.

For example, Ngo Poon Khiam and Ng See Kim Kelvin had engaged in a conspiracy to transact in shares in Chuan Soon Huat Industrial Group Ltd, which had the effect of creating a false or misleading appearance with respect to the market for such shares, and were duly convicted under section 197(1)(b) of the SFA read with section 109 of the Penal Code (Chapter 224). Apart from the financial penalties of S$200,000 and S$180,000 respectively imposed on them, POs were issued under the SFA against both of them which prohibited them from carrying on business in any regulated activity under the SFA, from acting as a representative in respect of any such regulated activity, and from taking part in the management of, acting as a director of, or becoming a substantial shareholder of any capital markets services licensee or exempt financial institution in Singapore, for a period of 4 years.

In another case involving insider trading, a PO was issued under the FAA against Koh Huat Heng prohibiting him from providing any financial advisory service and from taking part in the management of, acting as a director of, or becoming a substantial shareholder of a financial adviser, for a period of 3 years, alongside a civil penalty of S$50,000.

In the case of POs recently issued or proposed to be issued in connection with contraventions of AML/CFT laws, the penalties appear to be significantly more punitive.

Tim Leissner (a former director of Goldman Sachs) was in March 2017 slapped with a 10-year PO that prohibited him from performing any regulated activity under the SFA and from taking part in the management of any capital market services firm in Singapore. This was based on him having issued an unauthorised letter to a financial institution based in Luxembourg, and having made false statements on behalf of Goldman Sachs, without the latter's knowledge.

MAS has also given notice of its intention to impose a lifetime ban on Jens Fred Sturzenegger (formerly of Falcon Bank), following his criminal convictions in Singapore for, inter alia, failure to disclose information on suspicious movement of funds by Low Taek Jho into and out of Falcon Bank.

MAS also gave notice of its intention to impose a lifetime ban on former BSI banker Yak Yew Chee and a 15 year ban on former BSI banker Yvonne Seah Yew Foong, again in connection with the 1MDB money laundering scandal.

Failure to comply with a PO

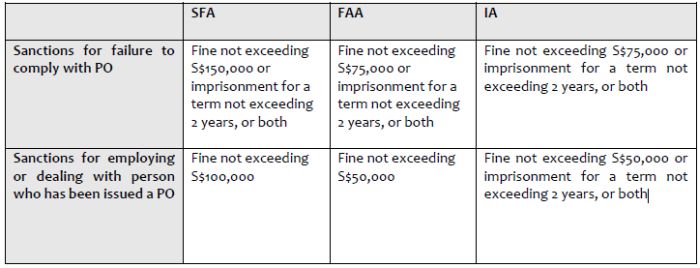

Failure to comply with the PO is a criminal offence under Singapore law with varying sanctions, which are briefly outlined in the table below:

Commentary

The move by MAS to resort to POs in relation to contraventions of AML/CFT laws – as well as the more substantive sanctions provided in each of the POs – underscores the firm policy stance that the regulator is taking on any misconduct action that could undermine trust and confidence in Singapore's financial system.

That having been said, one should not at the same time be unduly alarmed at the harsh regulatory response. MAS has also continued to reiterate that it will exercise its power to issue POs only in egregious cases, for example where there is clear misconduct that reflect a lack of honesty and integrity.

All things considered, the present regulatory reaction to the 1MDB scandal in Singapore continues to emphasise the need for financial institutions to have appropriate and proportionate measures to address money laundering risks. A financial institution should not only ensure effective customer due diligence procedures, and the effective monitoring of suspicious transactions, but it should also consider implementing appropriate reporting or whistleblowing procedures that ensure the anonymity of informants. This would enable appropriate action to be taken by the authorities on a timely basis.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.