The UK, like most other European governments, are facing increasing pressure on their health budgets. One of the reasons for this is the acceleration of medical innovations which are increasing the demand for state-of-the-art treatment. As a result, governments need to get more value for their spending and are considering how best to incentivise "value-based healthcare" (outcomes of health treatment relative to cost).

For most European countries these considerations are still at a relatively nascent stage. In the US, however, encouraged by a consensus amongst payers, the system is moving quickly from a volume-based system to one that is value-based. This week's blog is brought to you by our US Principal and Life Sciences Sector Leader, Greg Reh, and considers how value-based payment models might impact the adoption of innovative treatments and cures:

Few would deny that the health care system is evolving. And, in the case of health care, evolution is a good thing. It has brought us new care delivery approaches, new treatments, and new technological advancements that have created tremendous value to patients. Now, the focus is shifting toward ways to curb rising health care costs while maintaining and even improving the quality of care patients receive today.

Payers – health plans, employers, and government entities – are working with providers to test new value-based care (VBC) payment models that shift the focus away from the number of services to the value of those services. But defining value is not easy, and the question remains, what does this mean for medical innovation and the life sciences industry?

Last fall, the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions and the Network for Excellence in Health Innovation (NEHI) convened 21 leaders across the health care system, including biopharma, medtech, health plans, providers, academics, non-profits, and patient groups to discuss this very question. Many important topics were discussed throughout the day, but the participants really sought to answer how medical innovation will be evaluated under VBC and how VBC models can evolve to encourage medical innovation.

The results, which were published in " Delivering medical innovation in a value-based world," are telling. Today, there is much uncertainty around how VBC and supporting policies might evolve. Even more uncertain is how medical innovation will be evaluated, much less rewarded, under these new models.

What is the impact if VBC models and policies do not consider how to support patient access to medical innovation? For one, today, many VBC models focus on process measures and short-term clinical measures, leaving out long-term clinical or quality of life improvements that medical innovation can bring. Some also have relatively few quality measures and instead emphasize improvement against financial goals. For example, the new mandatory Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement bundled payment model only includes two quality measures. For providers working under these models, there is a risk that they will consider short-term cost over quality improvements, deterring them from using more expensive advanced technology.

Finally, we already see many providers participating in VBC arrangements standardizing their care pathways to achieve cost-effectiveness goals emphasized by these new payment models. Standardization may leave little room for provider adoption and patient access to breakthrough technologies that challenge existing standards of care. How can we make exceptions so that patients can access breakthrough innovation and payers and providers can test cost-effectiveness in the real world?

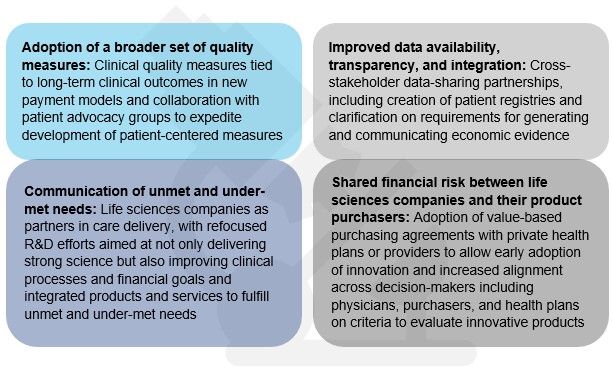

The conversation at Deloitte and NEHI's convening led us to identify four changes that may help integrate medical innovation into VBC models. Most importantly, the discussion pointed to the need for ongoing cross-stakeholder dialogue, specifically, giving life sciences companies a more prominent seat at the table.

Evidence from the field suggests that a few "early adopters" are already heeding the message that cross-stakeholder discussions are needed to bring medical innovation to patients under VBC. Just last month, Cigna and Novartis agreed to performance-based pricing for Entresto, a new drug for the treatment of heart failure. Under the deal, Cigna will pay Novartis based on how well the drug improves the health of heart failure patients in Cigna's commercial business. Novartis will be measured on how well the drug reduces the number of patients with heart failure hospitalizations. 1

In another recent collaboration, Eli Lilly and Anthem joined together to suggest policy solutions that may remove regulatory barriers that are impeding additional similar value-based payment arrangements today. The two companies said in a recent Health Affairs blog that anti-kickback statutes and government price calculations may need to be reconsidered before additional value-based collaborations can move forward. 2 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is also joining the conversation, most recently announcing it will test new ways to pay for drugs covered under Medicare Part B payments to physicians and hospitals. 3

In the not-to-distant future, medical innovation will likely be measured against an evolving definition of value, based on clinical and economic factors, as well as the ability of products to optimize care delivery. Life sciences companies should consider engaging health plans, providers, consumers, and policymakers now to shape how the value delivered by their products will be assessed in that future state. This will likely call for ongoing conversation among all health care stakeholders to ensure that this definition of value gives patients access to today's and tomorrow's life-changing innovations.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.