Given the menagerie of terms, it is easy to see why some business owners are quite confused about what to do when they are asked to permit an animal in their places of business. Part of the confusion comes from the multitude of federal laws on the topic (not to mention laws passed by some state and local governments). There is one for housing providers, another for those providing goods and services, yet another for airlines, and finally, one for employers. Another reason for the confusion is that these laws often use similar terms that have slightly different meanings.

In order to dispel the confusion under federal law, let's examine a hypothetical scenario. Imagine that Acme Apartments, a business that leases apartments, has a no-pet rule for its tenants and an office policy prohibiting pets in the workplace. Acme also operates a fitness center for tenants and the general public with a no-animal policy. In this situation, Acme will need to follow the Fair Housing Act (FHA), Title I of the American Disabilities Act (ADA), and Title III of the ADA. How each of these laws apply to Acme—and your business—is described below.

Assistance Animals And The FHA

Acme's pet restrictions are generally lawful. However, under the FHA, Acme must allow tenants and applicants with a disability to live with assistance animals that meet their disability-related needs. The only exception to this requirement is if the assistance animal would pose a direct threat to others or would cause substantial physical damage to property.

What constitutes an assistance animal is interpreted broadly. It could be a dog or any other animal that "works, provides assistance, or performs tasks for the benefit of a person with a disability, or provides emotional support that alleviates one or more identified symptoms or effects of a person's disability." Assistance animals will typically perform functions like providing protection or rescue assistance, fetching items, alerting persons to impending seizures, or providing emotional support to persons with disabilities who have a disability-related need for such support. In this context, assistance animals are sometimes referred to as "service animals," "assistive animals," "support animals," or "therapy animals." However, the preferred term is assistance animals to avoid confusion with other laws.

Service Animals And Public Accommodations Under The ADA

The legal requirements differ depending on whether you are considering accommodations in public places or in the workplace.

In Public Places

Title III of the ADA requires businesses that provide goods or services to the public to allow service animals to accompany people with disabilities in all areas of its facility in which the public is normally allowed access. Going back to Acme, this means that it must accommodate service animals in its leasing office and fitness center for visitors and patrons with a disability.

However, under Title III, service animals are limited to only individually trained dogs and, with some exceptions, miniature horses. Most often, service animals perform functions like guiding the blind, alerting the deaf, pulling wheelchairs, providing seizure alerts, or calming a person during an anxiety attack. Service animals do not include untrained comfort animals, which are generally animals that provide psychological comfort by their existence. In other words, no rabbit, bird, cat, monkey, or untrained dog can qualify as a service animal under the ADA in this context.

So how would Acme know if a dog or miniature horse is a service animal? Under the ADA, Acme is allowed to ask whether the animal is a service animal and what tasks the animal has been trained to perform, but nothing more. Acme cannot require proof of disability, certification, or make any other inquiry.

However, if the owner cannot maintain control of the service animal, or if the service animal proves dangerous or disruptive by its conduct, then Acme can expel it from the premises. Because of this limited inquiry, and the fact that many pet owners are apparently now attempting to pass their pets off as service animals, a growing number of states are making it a crime to misrepresent a pet as a service animal or misrepresent oneself as a person with a disability to gain access with a dog. Arizona, California, Minnesota, New Jersey, and Texas now have criminal penalties including jail time for such misrepresentations, with more states looking to follow.

In The Workplace

What about employees who request to bring animals into the workplace? Assume that one of Acme's employees says that she has an anxiety disorder and would like to bring her pet rabbit to work. She explains that it helps mitigate the disorder and allows her to perform her duties. Must Acme allow the rabbit in the workplace? To answer this question, employers must turn to Title I of the ADA.

Title I of the ADA requires that Acme, when asked, provide reasonable accommodations to qualified employees with a disability in order to allow the employee to perform the essential functions of the job. Acme is obligated to provide reasonable accommodations unless it would create an undue hardship.

When such requests are made, the employer should engage in an interactive discussion with the employee to learn about the employee's disability, how it is impacts the employee's major life functions, and how it may be impeding getting the employee's job duties done. In this process, it is important to highlight that employers must only provide a reasonable accommodation, and not the preferred accommodation requested by the employee if effective alternatives exist. In other words, if the employer can provide an alternative to the accommodation requested that is effective in allowing the employee to perform the job functions and is more in line with the needs of the employer, then the employer can provide that alternative and meet its ADA obligations.

As a practical matter, after engaging in the interactive process, most employers will discover that there are likely reasonable alternatives to permitting comfort animals in the workplace—but few to none regarding service dogs. In the rare case of a comfort animal request, some employers have offered less disruptive alternatives such as the use of a pet monitor at work or the use of a stuffed animal likeness. To date, there are no known cases in which a court has found an employer in violation of the ADA for denying the work presence of an untrained comfort animal where an alternative has been offered.

In contrast, a trained service dog accompanying an employee to their job has long been viewed as a "reasonable accommodation" under Title I of the ADA, even though not specifically listed as part of that section. There are a number of cases in which employers have been found to have violated the law by not permitting service dogs in job interviews or at work. In fact, the EEOC is currently pursuing a federal lawsuit against a trucking company for violating the ADA by not allowing a military veteran truck driver to complete his training with a trained service dog who provides "emotional support" and mitigates his post-traumatic stress and mood disorder.

However, employers may still deny these animals in the workplace if the employer can show the rare circumstance that it would create an undue hardship to operation of the employer's business. Under the ADA, undue hardship is defined as an "action requiring significant difficulty or expense" when considered in light of a number of factors. Examples of undue hardship in this context may include safety issues caused by the presence of the dog, the presence of other employees with dog allergies, or coworker phobias. Claiming undue hardship is a very narrow exception under the law and businesses who wish to use it should seek advice from legal counsel.

Conclusion

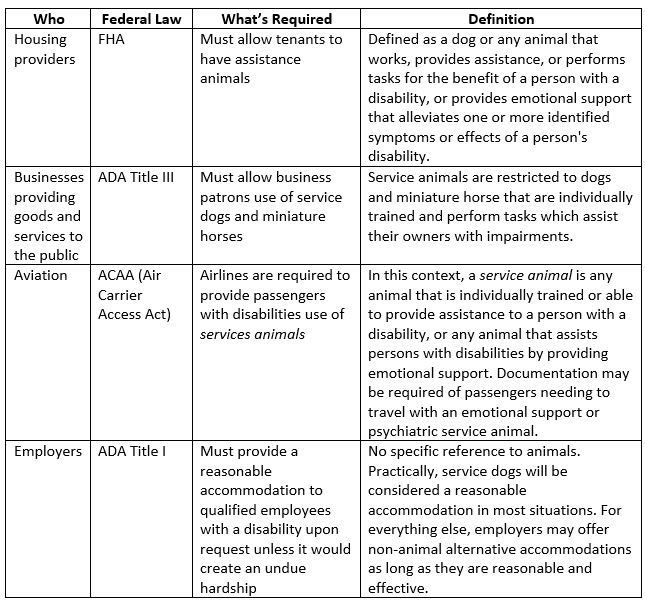

As with any regulated area, businesses subjected to the above laws should seek the assistance of counsel when drafting policies and developing staff training materials. Based on the multiple laws and definitions regarding assistive and service animals, it is no wonder that businesses, employers, and the general public are often confused about their rights and obligations. To help clarify, below is a chart that may help provide some order:

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.