The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (Recovery Act) executive compensation and corporate governance provisions retroactively amend the requirements under the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (Stabilization Act). The provisions impact recipients of federal funds under the programs authorized by the Stabilization Act, formerly known as the TARP programs. The U.S. Department of the Treasury (Treasury) published executive compensation regulations under the Stabilization Act and new regulations to reflect the amendments of the Recovery Act are expected shortly. Given the retroactive application of the amendments, Treasury is under pressure to provide interpretive guidance to hundreds of institutions, and dozens of individuals, covered by the new law.

Notwithstanding the absence of final regulations, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), concurring with Senator Dodd's1 assertion that the Recovery Act's say-on-pay provisions are immediately effective, has issued compliance disclosure interpretations2 to guide public company recipients of TARP funds during the current proxy season.

Below we discuss the executive compensation and corporate governance restrictions under the Recovery Act. For more information about the government intervention efforts in response to the financial crisis, please see our Client Alerts and resources at Financial Crisis Legal Updates and News.

Applicability to Recipients of Stabilization Act Funds

On February 10, 2009, Treasury and the Administration released an overview of their new Financial Stability Plan, a six-pronged program to provide stability to the financial system and a companion to the Recovery Act's stimulus package. The Financial Stability Plan combines the efforts of Treasury under the Stabilization Act's Troubled Assets Relief Program, or TARP, with new programs from Treasury, the Administration, banking regulators and other government agencies. Although the Administration's terminology has shifted from TARP to Financial Stability Plan, only participants that receive funds from programs under the Stabilization Act's TARP, and that issue securities to Treasury, bear the burden of this unique set of executive compensation and corporate governance requirements. For ease of reference, the parties for whom these laws and regulations apply are called "fund recipients" throughout this Client Alert.

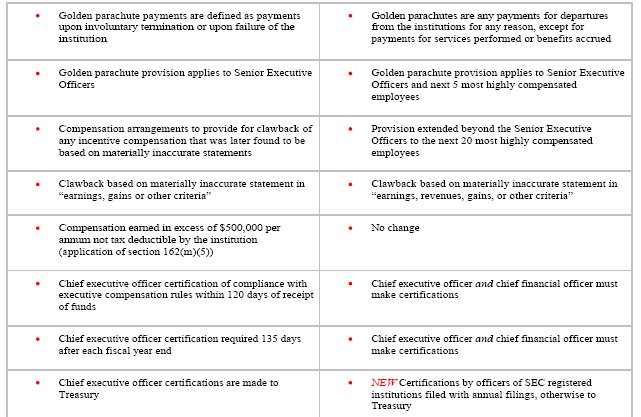

The Recovery Act's changes to Section 111 of the Stabilization Act amend existing compensation requirements and create new obligations for fund recipients, such as mandating the creation of compensation committees, limiting "luxury" expenditures, creating say-on-pay shareholder voting rights and imposing a new compensation clawback right on the 25 most highly paid executives. In many instances, the Recovery Act went further than stricter compensation restrictions proposed by Treasury in January 2009. Below we have provided a chart comparing the Stabilization Act core executive compensation requirements to the Recovery Act's amended versions, followed by a more detailed discussion of the new Recovery Act provisions.

Unless otherwise stated, the applicable requirements expire when Treasury no longer holds securities of the fund recipients. Under the Recovery Act, if Treasury only holds warrants to purchase common stock of the fund recipients, the executive compensation provisions will no longer apply. Presumably, if Treasury later exercises that warrant and holds the underlying common shares, the rules would once again be applicable a situation that fund recipients will assuredly work to avoid.

Executive Compensation Changes Chart

The following chart summarizes the Recovery Act executive compensation provisions, highlighting changes from the Stabilization Act. As noted, Treasury has issued regulations under the Stabilization Act and has not yet done so for the Recovery Act provisions.

Golden Parachutes

Treasury's current regulations prohibit golden parachute payments. As currently defined, however, these include only those payments that are (1) at least three times the base compensation and (2) payable upon the involuntary termination or insolvency, bankruptcy filing or receivership of the institutions.

The Recovery Act provides a statutory definition of golden parachute payment: any payment to a Senior Executive Officer for departure from a company for any reason, except for payment for services performed or benefits accrued. These payments are impermissible to the Senior Executive Officers and the next five most highly compensated employees.

As with the other provisions of the Recovery Act, this amendment reflects Congress's reaction to media reports that highly compensated executives at troubled institutions and institutions receiving taxpayer funds have received inappropriately generous packages when departing.

Clawback Provisions

The existing regulations require that the Senior Executive Officers agree to return any incentive compensation, including the proceeds of any securities-based compensation, which was paid based on materially inaccurate financial statements or performance metric criteria. If the payment is made or accrues to the individual during the period Treasury holds the investment, the recovery can occur at any point in the future, including after the securities held by Treasury have been redeemed.

The Recovery Act's group of individuals from whom recovery may be sought is extended beyond the Senior Executive Officers, to include the next 20 most highly compensated employees. As drafted, there is no requirement that this group of individuals be executive officers, a meaningful distinction for Wall Street firms that may award significant performance-based bonuses to non-executive officers. However, as discussed in the next section, the likelihood of this group of individuals having meaningful incentive compensation is reduced if their employer is a fund recipient receiving significant funds under Treasury's programs.

No Bonus, Retention Award or Incentive Compensation and Other Compensation Limits

Recently, several chief executive officers and similarly situated executives have taken highly publicized reductions in pay. These reports, however, were overshadowed by disclosure of significant bonuses throughout the financial industry, including an estimated $18 billion in year-end bonuses being paid on Wall Street.3 As a result of these reports, provisions were included in the Recovery Act to limit bonuses, retention awards and incentive compensation by fund recipient's highly compensated employees. The restriction limits the permitted compensation to restricted stock equal to no more than one-third of the employee's annual compensation. The restricted stock may not fully vest during the period Treasury holds the institution's securities. Treasury is authorized to impose additional terms and conditions that it determines are in the public interest. The group of employees covered by the restriction expands, based on the amount received from Treasury, as follows:

The statute carves out any bonus or similar payment that is required to be paid under a written contract executed prior to February 11, 2009. Treasury is authorized to determine the validity of the employment contract.

The Recovery Act also calls for standards prohibiting compensation plans that would encourage the manipulation of reported earnings to enhance the compensation of any employee, and prohibits compensation that includes incentives for the Senior Executive Officers to take unnecessary or excessive risks that threaten the value of the fund recipients.

As noted with other Recovery Act provisions, the impacted employees are not limited to executive officers. This constitutes a policy shift away from imposing restrictions on those executives charged with running those institutions that ultimately required government assistance – which have been seen as the group whose "failure" should not be rewarded in the public's mind. The Recovery Act goes a step farther, placing Treasury in the executive suite, making compensation decisions regarding Senior Executive Officers as well as employees that lack the authority to direct the actions of the fund recipients. Institutions focused on the attraction and retention of employees receiving performance-based compensation are appropriately concerned, given the potential competitive disadvantage in which they find themselves. An inability to compensate based on performance may result in institutions losing their highest performing employees when needed most.

Say-on-Pay

The Recovery Act requires that fund recipients seek non-binding shareholder approval of executive compensation as disclosed pursuant to SEC rules. This "Say-on-Pay" vote, as noted, is not binding on compensation committees or the board. The statute further clarifies that the vote does not "create or imply any additional fiduciary duty" by the board. Nevertheless, boards will need to consider carefully appropriate reactions to any significant vote against executive compensation. "Say-on-Pay" has been a fixture of the broader corporate governance debate over the last several years, and has been advanced by shareholder proponents and legislators as a means of providing shareholder input into the executive compensation process. Similar advisory votes on executive compensation have been implemented in other countries, such as the United Kingdom and Australia.

On February 20, 2009, Senator Dodd, Chairman of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs sent a letter to SEC Chairman Mary Shapiro requesting action on the Say-on-Pay provisions of the Recovery Act. Specifically, Senator Dodd expressed his view that the provision was effective and would apply to proxy statements filed with the SEC after February 17, 2009. Preliminary proxy statements filed before the effective date of the Recovery Act, February 18, 2009, and any related subsequently filed definitive proxy statements would not be subject to the provisions.

In response to Senator Dodd's letter, the SEC's Division of Corporation Finance published Compliance and Disclosure Interpretations (C&DIs) regarding the Recovery Act for issuers preparing to file proxy statements. The C&DIs make clear that upcoming annual meetings for the election of directors must include an opportunity for shareholders to vote on an advisory company-originated proposal on executive compensation. Inclusion of a shareholder proposal regarding executive compensation would not necessarily satisfy the new statutory requirement. The proxy must include a vote specifically on the compensation of executives as disclosed under SEC compensation disclosure rules and the C&DIs note that many shareholder proposals call for a precatory vote on whether the institution should to adopt a policy providing for an annual vote on executive compensation, as opposed to an actual advisory vote on executive compensation. Such a proposal would not satisfy the requirements of the Recovery Act.

Under the guidance, the "Say-on-Pay" provision of the Recovery Act applies to preliminary or definitive proxy statements (other than definitive proxy statements which relate to preliminary proxy statements filed on or before February 17, 2009) filed with the SEC after February 17, 2009. Fund recipient public companies that did not have preliminary proxy statements on file by February 17, 2009 need to incorporate the Say-on-Pay vote into their upcoming annual meetings. Say-on-Pay proposals will require public fund recipients to file preliminary proxy statements, and potentially have to work out timing accommodations with the SEC Staff in order to meet mailing deadlines. Given that the legislation includes no exemption for fund recipients that are not public, private fund recipient institutions may be under time constraints similar to public companies depending on the timing of upcoming annual meetings for the election of directors, particularly given the requirement that shareholders have access to disclosure modeled on SEC requirements.

Luxury Expenditures

As financial institutions accepted taxpayer funds, media reports highlighted a series of luxury and perceived excessive corporate expenditures and planned expenditures generating criticism over institutions' judgment and ethics and the government's ability to protect taxpayer funds. In reaction to these highly publicized reports, the Recovery Act includes a limitation on luxury expenditures provision. A fund recipient's board of directors is required to approve a firm-wide policy regarding excessive or luxury expenditures. While Treasury is directed to identify "excessive or luxury expenditures," the Recovery Act provides, by way of example, the following list:

- Entertainment or events; Office and facility renovations;

- Aviation or other transportation services; and

- Other activities or events that are not reasonable expenditures for staff development, reasonable performance incentives or other similar measures conducted in the normal course of business operations.

The Recovery Act does not mandate specific limits or prohibitions on spending, and Treasury regulations are not yet available, but boards are expected to consider carefully the optics of these expenditures and the need to avoid the public trials of industry peers. The final category, which refers to spending outside the "normal course of business," may provide a reasoned approach to the development of these policies. At the same time, boards will want to consider carefully whether new expectations regarding expenditures and the board's obligations regarding oversight of government funds requires new policies with enhanced reporting to the board or with new thresholds for board approval of specified categories of corporate expenditures.

Compensation Committees and Certifications

Under current regulations, the compensation committee, or "a committee acting in a similar capacity," is required to make certifications (1) to the SEC if a reporting company, in the Compensation Committee Report required with the annual report on Form 10-K and (2) if not an SEC reporting company, to Treasury. The committee must certify that it has reviewed the senior executive officers' compensation arrangements to ensure that there are no incentives to take unnecessary or excessive risks that threaten the value of the institution. Additionally, the committee must certify that it has met, on no less than an annual basis, with senior risk officers to discuss and review the relationship between the institution's risk management policies and practices and senior executive officers' incentive compensation arrangements.

The Recovery Act does not expressly require any additions to the compensation committee certification requirements. However, the Recovery Act eliminates, with one exception, the ability of a committee acting in a similar capacity as a compensation committee to take the required actions and make the required certifications. The creation of a board compensation committee, comprised exclusively of independent members, is required of all funds recipients. As noted there is one exception: a recipient of less than $25,000,000 in funds that is not a public company is not required to form a compensation committee. The board of any such institution is required to act in the place of a compensation committee of the board.

The compensation committee, or board in the limited case described above, is required to meet no less than twice per year to discuss and evaluate employee compensation plans in light of an assessment of any risk posed to the institution from such plans.

Also, under current regulations, principal executive officers are required to provide certifications. First, within 120 days of receiving funds, the chief executive officer is required to certify to Treasury satisfactory completion of a review of senior executive officers' compensation arrangements and applicable regulations to ensure the compensation arrangements do not encourage unnecessary and excessive risk taking. After each fiscal year, the chief executive officer is required to certify to Treasury that the institution, including the compensation committee, has complied with the executive compensation regulations.

The Recovery Act extends the certification requirements to the chief financial officer. The chief executive officer and chief financial officer are required to make their certifications to the SEC with the annual report, if the funds recipient is a public company. Otherwise the chief executive office and chief financial officer certifications are made to Treasury.

The guidance provided in Senator Dodd's letter (which is being followed by the SEC) indicated that this certification requirement relates to compliance with standards that have not yet been established by Treasury, and therefore is not yet effective, so chief executive officers and chief financial officers will not be required to certify as to their fund recipients' compliance until the standards have been established.

Prior Payments to Executives

As noted, there has been significant media coverage of executive compensation and employee bonuses following the investment by Treasury of several billion dollars in taxpayer funds into financial institutions and automotive companies. The Recovery Act mandates that Treasury will undertake a review of the bonuses, retention awards and other compensation paid to the senior executive officers and the next 20 most highly compensated employees of each fund recipient that received funds prior to enactment of the Recovery Act. Treasury will determine if any payments were "inconsistent with the purposes of [the executive compensation provisions of the Recovery Act] or the TARP or were otherwise contrary to the public interest." If Treasury makes such a determination it must negotiate with the fund recipient and the employee for an "appropriate reimbursement" to the federal government.

Treasury has not released information about its plans under this provision, leaving highly compensated employees of fund recipients with some very open-ended questions about their compensation.

Conclusion

The executive compensation provisions of the Recovery Act represent the culmination of a rising level of public anger over the compensation practices of financial institutions, and are largely in reaction to the particular issues that have had a high profile in the media. As a result of the rush to judgment on many of these provisions, many fund recipients may find their overall employee compensation programs significantly disrupted at a time when they are facing unprecedented challenges in maintaining a motivated and committed workforce. Further, fund recipients will face significant distractions this proxy season as "Say-on-Pay" proposals are rushed onto their ballots, with little time to prepare shareholders, advisory services and others for the import of these largely untested advisory votes. Clear standards on a wide variety of open issues arising under the Recovery Act will be required from the SEC and Treasury in order for fund recipients to make appropriate compensation choices and disclosures in the near term.

Footnotes

1 Senator Dodd's letter dated February 20, 2009 to Chairman Mary Shapiro is available at http://banking.senate.gov/public/_files/022009_ChairmanDoddlettertoSECChairmanSchapiroonexecutivecompensationlegislation.pdf .

2 The Division of Corporation Finance's Compliance and Disclosure Interpretations regarding the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, as revised, are available at http://sec.gov/divisions/corpfin/guidance/arrainterp.htm .

3 See "Shameful" posted on The White House Blog on January 29, 2009, available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog_post/Shameful /.

Because of the generality of this update, the information provided herein may not be applicable in all situations and should not be acted upon without specific legal advice based on particular situations.

© Morrison & Foerster LLP. All rights reserved