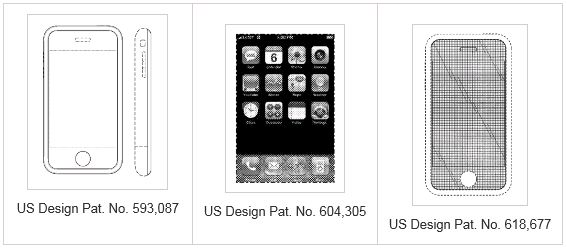

The oft-overlooked design patent has seen somewhat of a revival recently (at least in the media) ever since a jury in California awarded Apple $399 million in damages — i.e., all Samsung profits from the sale of several of its smartphone and tablet devices — for Samsung's infringement of three Apple design patents in Apple, Inc., v. Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd.

The statute (35 U.S.C. § 289) that dictates damages for infringement of design patents states that "[w]hoever ... applies the patented design, or any colorable imitation thereof, to any article of manufacture for the purpose of sale ... shall be liable to the owner to the extent of his total profit...." Consequently, damages available for infringement of a design patents can be greater than damages available for infringement of a utility patent, which typically is set at an amount equal to a reasonable royalty per 35 U.S.C. § 284. A reasonable royalty being a percentage of the infringer's profit, not the total profit as awarded by the design patent statute.

While design patents usually offer a far narrower scope of protection than utility patents, the potential for damages can be far greater in light of Federal Circuit precedent requiring disgorgement of profits for the whole product that embodies the infringed design.

Samsung has since filed a request for the Supreme Court to review the Federal Circuit decision upholding the damages award. Samsung argues that damages for design patents should be limited to the profits attributable to the infringing component only, and not the product as a whole. Samsung argues that section 289's use of "article of manufacture" is undefined by the statute and just means a component of the "infringing product," and therefore apportioning the damages to the profit attributable to that component would not be at odds with the statute. Samsung argues that this interpretation would bring design patent damages inline with utility patent damages. Various amicus briefs have been filed in support of Samsung's petition urging the Supreme Court to limit design patent damages. Those in support of Samsung's position include the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Dell, eBay, Facebook, HP, Hewlett Packard, various intellectual property professors, and the Computer & Communications Industry Association.

Cases since the Federal Circuit decision upholding the $399 million damages award to Apple have led to rather harsh outcomes for adjudicated infringers. In a case where the defendant was found to have infringed a design patent covering merely the front-end of a hydraulic dock leveler, a jury awarded $46,825 in damages. The Federal Circuit, relying on the Apple v. Samsung doctrine, stated on appeal that the damages should have been the profits for the entire dock leveler system. Nordock, Inc. v. Systems Inc., 2:11-cv-118 (Fed. Cir. Sept. 29, 2015). A district court in Pacific Coast Marine Windshields v. Malibu Boats awarded the holder of a boat windshield design patent all of the profits from the entire boat. A recent case filed by Microsoft, Microsoft Corporation v. Corel Corporation, may result in Corel having to disgorge its entire profits from Corel Write based on Corel's use of a zoom bar in the bottom-right of the word processor's window.

To-date, no one formally supports the counter-argument posited by Apple.

The counter argument to Samsung's is that in limiting damages to the component of a product that embodies the design would counteract Congress' express rejection of the "apportionment" requirement. (See Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., citing Nike, Inc. v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc.) Prior to 1887, a design patent holder would have to determine the amount of an infringer's profit that was attributable to the patented design, and provide proof for that amount. In 1887, Congress specifically removed this requirement for design patents from 35 U.S.C. § 289. Instead, an infringer of a design patent "shall be liable to the owner to the extent of his total profit."

While it appears that the industry generally supports Samsung's position that damages for infringement of a design should be limited to the profits attributable to just the component embodying that design, it would appear that if the Supreme Court found in favor of Samsung it would be undoing Congress' express intention of doing away with the apportionment requirement. Should the Supreme Court hear the case, we may find that it finds in favor of Apple, with a strong recommendation to Congress to change the law.

We will find out whether the Supreme Court is willing to weigh in on this matter shortly. The case is up for discussion at the Supreme Court's March 4, 2016 conference. As most major patent and trademark cases have been decided (typically against the patentee) unanimously by the justices, Justice Scalia's passing is likely to have zero effect on the outcome of this case.

While design patents have received attention recently in the patent press, it has had little effect on the rate at which applications for design patents have been filed. The rate at which all types of patent applications have been filed has been steadily increasing since the 1960s per the U.S. Patent Statistics Chart, Calendar Years 1963-2014. There has been no sudden change to that trend in the last couple of years.

Design patents, once looked down on by the patent industry due to their ease to obtain and the narrow protections they offer, are holding their own as being valuable assets for a company to obtain. Good design is key to being successful in today's economy. Consumers just do not buy products with bad design, they expect a good user experience. As Steve Jobs said "[d]esign is the fundamental soul of a human-made creation that ends up expressing itself in successive outer layers of the product or service." Design patents can be used to bolster the protection of that user experience. Any attempt to replicate that user experience may fall foul of a design patent. Thus, a design patent can be a powerful tool to block a competitor from stealing your designed user experience.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.