The application of competition law to standard essential patents (SEPs) has been the subject of significant debate. The latest instalment was provided by the Court of Justice on 16 July 2015 with its much-anticipated preliminary ruling in Huawei v. ZTE, which concerns the circumstances in which an (presumptively dominant) SEP holder who has given a FRAND commitment may seek injunctive relief without infringing EU competition law.

Given that the conduct at issue concerns allegedly abusive use of the processes of EU national courts, it is both surprising and disappointing that the ruling from Europe's highest court ignores the established EU competition law standard on abusive litigation. It would seem that the Court of Justice has also conflated the questions of when an injunction should be granted with when it would be abusive merely to request one from a national judge. Instead, the Court of Justice has designed a novel legal standard that firms involved in licensing will likely find both incomplete and detached from reality, and which will result in significant uncertainty.

This note explains and analyses briefly the license negotiation procedure proposed by the Court of Justice for SEPs in respect of which a FRAND commitment has been given. It also explains and analyses some of the more obvious shortcomings of the ruling.

BACKGROUND

The Landgericht Düsseldorf (Germany) made a request for a preliminary ruling in the course of a dispute between Huawei Technologies and ZTE, two Chinese companies active in the telecommunications sector. Huawei sought an injunction against ZTE for alleged infringement(s) of its SEPs. ZTE claimed that Huawei's action was in itself an abuse of a dominant position as Huawei had committed to license its declared SEPs on "FRAND" terms1 and ZTE was "willing" to negotiate such a licence.

The Landgericht Düsseldorf made a "preliminary reference," essentially asking the Court of Justice whether an application for injunctive relief by an SEP holder who committed to license its SEPs on FRAND terms could be resisted on the grounds that the application amounts to an abuse of a dominant position under EU competition law, and if so in what circumstances. The German court did not ask any questions on market definition and dominance, as in the underlying litigation Huawei's dominance was apparently not disputed.

On 16 July 2015, the Court of Justice provided its responses to the German court's questions. The Court of Justice's ruling concerned merely its interpretation of EU competition law as a matter of principle, leaving the German court the (unenviable) task of applying the ruling to the underlying dispute.

The Court of Justice's ruling follows, and was in fact triggered by two controversial decisions adopted by the Commission in 2014, Samsung and Motorola,2 which purport to provide guidance as to the circumstances in which the holders of SEPs may seek (and enforce) injunctive relief without infringing EU rules on abuse of dominance.

A NOVEL FORM OF ABUSE

Relying on the "particular circumstances of the case,"3 the Court of Justice distinguishes the present case from its well-established and settled case law according to which "the exercise of an exclusive right linked to an intellectual-property right [(IPR)] by the proprietor may, in exceptional circumstances, involve abusive conduct."4 The Court of Justice also appears to have considered a request for an injunction as analogous to a refusal to license,5 which is clearly not the case.

The Court of Justice is of the view that "in order to prevent [the seeking of injunctive relief] from being regarded as abusive, [an SEP holder] must comply with [certain] conditions."6 Those conditions are set out sequentially in the ruling, as if they would be embodied in the SEP holder's FRAND commitment.7 Yet, these conditions are unsupported by any reference to specific industry precedents, common practice within standard setting organizations, or evidence that they would correspond to widely-recognized commercial practices. Specifically, the FRAND commitment given in respect of the litigated patents does not include any restrictions on seeking injunctive relief.

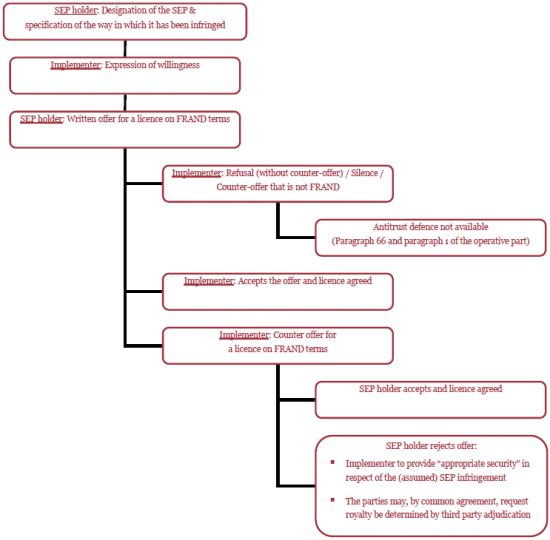

According to the Court of Justice, an SEP holder who has given a FRAND commitment (and who is also dominant) will not infringe Article 102 TFEU by seeking injunctive relief "so long as" the following steps are being complied with:

- Step 1: Prior to bringing that action, the SEP holder has first informed the implementer of the infringement complained about by (i) designating that (ed. note: presumably single) SEP and (ii) specifying the way in which it has been infringed;

- Step 2: The implementer has then "expressed its willingness to conclude a licensing agreement on FRAND terms." If there is no such expression, the SEP holder can presumably seek – and obtain and enforce – an injunction without fear of antitrust liability;

- Step 3: Following this, the SEP holder has presented a "specific, written offer for a license on [FRAND] terms," specifying the royalty amount and calculation methodology; and

- Step 4: Finally, the implementer has diligently responded to that offer, "in accordance with recognised commercial practices in the field and in good faith ... which implies, in particular, that there are no delaying tactics."8 Again, if there is a failure to respond diligently, a lack of good faith and/or any "delaying tactics" (concepts upon which unfortunately the Court of Justice does not expand), the SEP holder can presumably seek – and obtain and enforce – an injunction.

The questions of the referring court assumed dominance in the case at hand, and the text of the ruling clearly states: "Given that the questions posed by the referring court relate only to the existence of an abuse, the analysis must be confined to the latter criterion."9 However, the operative part contains no explicit limitation to SEP holders that have been proved to be dominant. Therefore, the ruling is open to misinterpretation and misapplication by those who would claim that the ruling necessarily applies to any SEP. Similarly, and in contrast to the Commission's position, the Court of Justice seems to accept that an SEP holder who has given a FRAND commitment will be found to have abused a dominant position only if the SEP in question is valid and essential to the standard – it is not sufficient that the patent in question was declared as being potentially essential to a standard.10 By the same token, the SEP must be infringed – although this may have been lost on the Court given that it appears unaware of the fact that not all SEPs will necessarily be used by a standard-compliant product.

Equally, the test set out by the Court of Justice does not consider what should happen in the event that each party makes an offer but they are unable to agree terms and conclude a license, which is of course an entirely unremarkable scenario in licensing negotiations. Also, notable by its absence from the operative part of the judgment is any reference to third party determination of licensing terms. However, earlier in its ruling, the Court of Justice states that if no agreement is reached the parties "may" (not "shall"), by "common agreement" (not by unilateral declaration of the implementer), request that the "royalty be determined by an independent third party ... without delay." It appears therefore that the Court of Justice considered and rejected the idea promoted in the Commission's Samsung and Motorola decisions that a solvent implementer should be immune from injunction requests if it unilaterally declares itself willing to have a court or arbitrator determine license terms.

Although fraught with uncertainty, in contrast to the Commission's Samsung and Motorola decisions, the Court of Justice appears to provide an (albeit limited) antitrust safe harbour for SEP holders and does not reverse the burden of proof in a manner that would make it incumbent upon the SEP holder to demonstrate that the implementer/infringer was not "willing" to agree a FRAND license. In accordance with the Court's test, it is arguably for the implementer who wishes to avail himself of the antitrust defence to demonstrate that he complied with the process set out in the ruling, including showing that he made a FRAND counter-offer. Indeed, arguably, the Court of Justice places significantly more duties upon the implementer (i.e., expression of willingness, diligence, good faith, and not employing delaying tactics) than the Commission did in its SEP decisions. That being said, the preliminary ruling does not address, at least in any meaningful way, what should happen in the event that an opening (FRAND) offer is made and rejected.11 Indeed, beyond the highly stylised scenario envisaged by the Court of Justice, it is not clear whether injunctive relief should be available at all and, if so, in what circumstances.

Figure 1: The Court of Justice's proposal for SEP licensing discussions

A formalistic process, detached from reality of licensing negotiations ...

The test proposed by the Court of Justice is formalistic and detached from the reality of licensing negotiations. It fails to take into account the following factors:

- Licensing offers and counter-offers are not necessarily made in neat, formal written documents setting out all the relevant terms, as such matters may only be determined at a later stage taking into account, e.g., the value of a cross licence;

- Licensing negotiations will almost always involve more than one exchange of an offer and a counter-offer. As in any normal negotiation, one would expect the seller to start high and the buyer to start low;

- Although patent infringement proceedings concern individual patents, licensing agreements generally cover the parties' entire IPR portfolios (a patent per patent approach is neither workable nor useful for businesses); and

- In any event, the test proposed by the Court of Justice does not seem to take into account that, in most cases, the stakeholders negotiate a cross-licence rather than two (or more) purely unilateral licences.

The proposed process leaves a number of "blanks" and refers to a large number of undefined concepts. This lack of clarity and detail results in unwelcome uncertainty:

- While the ruling in Huawei v. ZTE makes it clear that the offer of Step 3 shall specify the amount of the royalty and the calculation methodology, key aspects remain unaddressed. Thus, it is unclear, for instance, whether the generally-accepted practice of negotiating cross-licensing agreements covering both firms' IPR portfolios would fulfil the requirement imposed by the Court of Justice.

- Both the offer and the counter-offer are supposed to contain a licence on "FRAND terms." Whether licensing terms can be qualified as FRAND depends on a number of elements which are usually subject to discussions between the negotiating parties. In the absence of any widely-recognized "one size fits all" benchmark against which to assess the "FRANDness" of licensing terms, the SEP holder is left with a process which, even if followed one step after the other, could still expose him to antitrust liability if its initial offer is subsequently qualified as not being FRAND. On the other hand, if the counter-offer proposed by the implementer is non-FRAND, this will presumably prevent the implementer from relying on an antitrust defence as a means to resist the request for an injunction but would not create any antitrust exposure. The imbalance that is thus created between SEP holders and implementers in turn creates a powerful incentive for SEP holders to accept licensing terms that are in fact well below what would still be FRAND.

- Courts and competition authorities appear to need to determine validity, essentiality, infringement and FRAND licensing terms before they can consider that an injunction request is abusive.12

- According to the Court of Justice, "where no agreement is reached on the details of the FRAND terms following the counter-offer by the alleged infringer, the parties may, by common agreement, request that the amount of the royalty be determined by an independent third party, by decision without delay."13 In case of a deadlock resulting from the absence of an agreement on licensing terms or on third party adjudication, can SEP holders break the deadlock by seeking injunctive relief? In the light of the judgment's lack of clarity, SEP holders could end up refraining from exercising rights they are entitled to by virtue of Directive 2004/48 on the enforcement of IPRs.14

- The implementer must "diligently" respond to the licensing offer "in accordance with recognised commercial practices in the field and in good faith ... which implies, in particular, that there are no delaying tactics." The interpretation of "recognised commercial practices" and "delaying tactics" by an SEP holder may however differ significantly from that by the potential licensee. Indeed, arguably, the Orange-Book-Standard procedure established by the German Supreme Court – which gave rise to the facts in this case and the Commission's Motorola decision – was recognised commercial practice. Here again, the risks associated with the lack of clarity surrounding these concepts are likely to hamper SEP holders in securing their rights.

... and to a large degree ignoring the requirement to measure "anticompetitive effects"

According to DG Competition's most senior official: "there is clear case law demanding an analysis of effects."15 With its formal approach, the Court of Justice attaches liability to a simple request to a national court to determine whether an injunction would be appropriate in the circumstances of a case, and in so doing severely limits the fundamental rights of access to court and to an effective remedy.

Seeming to assume that every injunction request by an SEP holder would automatically be granted, which of course is not true, the Court of Justice states: "the fact that that patent has obtained SEP status means that its proprietor can prevent products manufactured by competitors from appearing or remaining on the market and, thereby, reserve to itself the manufacture of the products in question."16 This language, which bears a striking resemblance to the Court of Justice's IMS Health and Magill rulings, gives the impression that the only cognisable antitrust harm in these circumstances is one of exclusion of (all) competitors. This impression is reinforced by the absence of any discussion of anticompetitive exploitation, or of controversial concepts such as patent hold-up and royalty stacking. In addition, it suggests that a request for an injunction by an SEP holder who does not compete with the alleged infringer cannot give rise to antitrust liability given that such SEP holder cannot – and has no incentive to – "reserve to itself" a downstream product market.

LEGAL UNCERTAINTY

As indicated above, the Court of Justice surprisingly makes no reference to the established and widely-accepted legal test on abusive recourse to a court of law initially developed by the Commission and then set out by the General Court in ITT Promedia17 before being explicitly endorsed by the same court in Protégé.18 This test defines the circumstances under which the initiation of legal proceedings could constitute an abuse of a dominant position, namely when the legal action (i) is manifestly unfounded, and (ii) proves to be part of a plan to eliminate competition. In Huawei v. ZTE, the Court of Justice does not explicitly (i) overrule the General Court19 or (ii) distinguish the present case from the two former cases which nevertheless addressed the circumstances under which lodging a judicial action could amount to an infringement under Article 102 TFEU. The absence of a single reference to the existing legal test on abusive recourse to a court renders its future very uncertain, not only in the so-called "particular circumstances of the case," but more broadly, in the case of any legal action by the holder of an alleged dominant position.

The Court of Justice also fails to recognise the legal safeguards provided by national legal systems, whereas it is recognised by DG Competition's most senior official that "the courts are specialist patent courts – which reduces uncertainty about the outcome."20

Inevitably, legal uncertainty in which the risk is borne by only one party (the SEP holder) skews negotiations in favour of the other party (the implement/infringer).

RELEVANCE

Although clearly significant, it seems unlikely that the ruling of the Court of Justice in this case will put an end to the debate and one could expect further questions being asked to the Court of Justice in the coming months or years.

For example, the Landgericht Düsseldorf proceeded (and phrased the questions it referred) on the assumption that an SEP holder holds a dominant position. The Court of Justice did not therefore decide upon the criteria for determining the relevant market and/or for finding a dominant position. However, since the question of dominance is central to the test – without a dominant position, there would be no abuse and an SEP holder would be entitled to seek injunctive relief in all circumstances – one can also expect disputes arising from the legal uncertainties created by the present ruling. In particular, it remains unclear whether, in licensing negotiations involving parties who each owns SEPs and has given a FRAND commitment, one party, the other, or both can be considered to hold a dominant position.

Footnotes

1. Huawei committed to license its SEPs under fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms and conditions during the standard-setting process in the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI). Under ETSI's rules of procedure, owners of SEPs are invited to give an irrevocable undertaking that they are prepared to grant irrevocable licenses on FRAND terms and conditions.

2. Commission decisions of 29 April 2014 in Case COMP/39.939 Samsung – Enforcement of UMTS standard essential patents and Case COMP/39.985 Motorola – Enforcement of GPRS standard essential patents.

3. Among those "particular circumstances", the Court of Justice mentions "the fact that the patent [...] is essential to a standard", which would imply, according to the Court, that the SEP holder "can prevent products manufactured by competitors from appearing or remaining on the market and, thereby, reserve to itself the manufacture of the products in question" (C-170/13 Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd. v. ZTE Corp., ZTE Deutschland GmbH, EU: C:2015:477 (C-170/13 Huawei Technologies), para. 49 and 52). The Court of Justice also considers that by committing to license its SEPs on FRAND terms, an SEP holder creates legitimate expectations on the part of implementers that the SEP holder would not refuse to grant licences on such terms (paras 53-54).

4. See cases cited in C-170/13 Huawei Technologies, para. 47.

5. C-170/13 Huawei Technologies, paras 52-54. A refusal to license by a dominant IPR holder is recognised in the case law of the Court of Justice as an abuse under Article 102 TFEU, only if certain "exceptional circumstances" are present.

6. C-170/13 Huawei Technologies, para. 55. For an analysis of the Opinion of Advocate General Wathelet, see here.

7. "[A]lthough the irrevocable undertaking to grant licences on FRAND terms given to the standardisation body by the proprietor of an SEP cannot negate the substance of the rights guaranteed to that proprietor by Article 17(2) and Article 47 of the Charter, it does, none the less, justify the imposition on that proprietor of an obligation to comply with specific requirements when bringing actions against alleged infringers for a prohibitory injunction" (emphasis added), C-170/13 Huawei Technologies, para. 59.

8. C-170/13 Huawei Technologies, paragraph 1 of the operative part.

9. C-170/13 Huawei Technologies, para. 43.

10. C-170/13 Huawei Technologies, para. 62.

11. There is a fleeting reference at paras 66-67 of the preliminary ruling, but no real consideration of the issue whether, in these circumstances, the mere seeking of injunctive relief could be considered abusive.

12. In its Motorola and Samsung decisions, the Commission was careful to avoid having to assess whether an offer was FRAND before it could conclude that an injunction request was abusive.

13. C-170/13 Huawei Technologies, para. 68.

14. See in particular Articles 9 and 10.

15. "The Object of Effects", speech delivered by Alexander Italianer at the CRA Annual Conference held in Brussels on 10 December 2014, available at http://ec.europa.eu/competition/speeches/text/sp2014_07_en.pdf.

16. C-170/13 Huawei Technologies, para. 52.

17. T-111/96 ITT Promedia NV v European Commission, EU: T:1998:183.

18. T-119/09 Protégé International Ltd. v European Commission, EU: T:2012:421.

19. As the EU's highest court, the Court of Justice is not formally bound by the judgments of the General Court, although the EU Courts are encouraged to ensure "unity or consistency of Union law" (see, e.g., Article 256 TFEU).

20. "Shaken, not stirred. Competition law enforcement and standard essential patents," speech delivered by Alexander Italianer at the Mentor Group – Brussels Forum in Brussels on 21 April 2015, available at http://ec.europa.eu/competition/speeches/text/sp2015_03_en.pdf.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.