Few courts have addressed antitrust challenges to pharmaceutical "product hopping," i.e., the practice of shifting customers from a drug nearing the end of its patent protection to a modified version that is covered by newer patents and thus is protected from generic competition for a longer period of time. The Second Circuit recently became the first Court of Appeals to do so in People of the State of New York v. Actavis, Case No. 14-4624 (2d Cir. May 28, 2015). It upheld a preliminary injunction prohibiting Actavis from ceasing production of an Alzheimer's drug in advance of its July 2015 patent expiration, a move Actavis intended to shift patients to an extended-release version of the drug which is patented through 2029. The decision has significant implications for the pharmaceutical industry and provides some guidance for branded pharmaceutical companies seeking to switch customers to a modified version of an older product or generic pharmaceutical companies seeking to challenge such conduct.

Legal Background

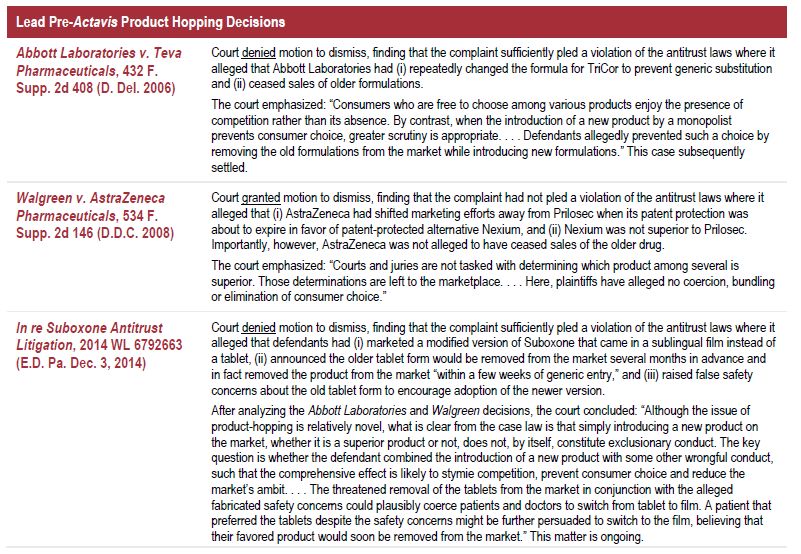

Application of the antitrust laws to drug makers' efforts to switch customers to a modified version of an older drug has been subject to much debate and little case law. Prior to the Second Circuit's recent decision in Actavis, only a handful of lower courts had confronted the issue.

The takeaway from those decisions (summarized in the following chart) was that merely introducing and marketing a modified version of a drug did not violate the antitrust laws, but doing so together with other conduct of arguably anticompetitive nature could give rise to a violation.

These cases involved private lawsuits, not government enforcement. The Second Circuit in Actavis nonetheless cited Abbott Laboratories and In re Suboxone Antitrust Litigation with approval, which is likely to give them enhanced precedential value going forward. Indeed, the Second Circuit's case law analysis closely matched analysis in those prior cases in justifying the application of the antitrust laws to product hopping and in finding a distinction with important legal implications between (a) giving customers a choice to switch to a new product and (b) forcing customers to switch to a new product.1

Actavis Litigation Background

In Actavis, the Second Circuit heard an appeal of a preliminary injunction issued by the US District Court for the Southern District of New York that prohibited Actavis PLC and its subsidiary Forest Laboratories (referred to together herein as "Actavis") from pulling Alzheimer's drug Namenda IR from the market prior to the July 2015 expiration of the drug's patent protection.

The underlying complaint, brought against Actavis by New York's Attorney General, alleged that Actavis violated the antitrust laws by planning to withdraw Namenda IR from the market before its patent protection expired in order to force patients dependent on the drug to switch to Namenda XR, a newer version covered by patents that did not expire until 2029.

The two drugs, which have the same active ingredient (memantine), differ in two ways: (1) IR needs to be taken twice a day, while XR is an extended-release formula that only needs to be taken once a day; and (2) IR is marketed in tablet form, while XR is marketed in capsule form.

Prior to filing the complaint, New York's Attorney General had obtained discovery through investigational demands and found evidence (e.g., internal documents) showing that Actavis' withdrawal had been expressly motivated by a desire to limit generic competition and thus avoid the "patent cliff" – i.e., the normal substantial drop in revenue for a branded drug that occurs once its patent protection expires and generics enter the market.

The district court held an evidentiary hearing on the Attorney General's motion for a preliminary injunction on November 10-14, 2014. The district court considered testimony either live or via affidavit from 24 witnesses and the parties presented over 1,400 exhibits. The Attorney General argued that the combination of introducing Namenda XR and withdrawing Namenda IR from the market prior to generic entry violated the antitrust laws by effectively forcing patients dependent on memantine to switch to XR and that the injunction sought was necessary to avoid irreparable harm. The Attorney General argued in particular that pharmacist substitution of a generic in place of a prescribed branded version of a drug was the only cost effective way for generics to compete and that withdrawal of Namenda IR from the market prior to the expiration of its patent protection would foreclose this avenue of competition.

Actavis argued that it would be unprecedented to force a company to continue manufacturing an older product to aid competitors, that its valid patents in Namenda IR gave it the legal right to discontinue its production, that the Attorney General had failed to prove any irreparable harm from discontinuing Namenda IR (and that in fact there would be no irreparable harm given the demonstrated safety of transitioning to XR), and that Actavis' withdrawal of Namenda IR had pro-competitive justifications (e.g., savings by focusing manufacturing on a single memantine drug).

The district court agreed with the Attorney General and, on December 11, 2014, issued a decision granting the preliminary injunction. The injunction obligated Actavis to continue to make Namenda IR "available on the same terms and conditions applicable since July 21, 2013 (the date Namenda XR entered the market)" until 30 days after the date when generic IR would be available.

Second Circuit Decision

The Second Circuit articulated the issue before it as follows: "under what circumstances does conduct by a monopolist to perpetuate patent exclusivity through successive products, commonly known as 'product hopping,' violate the Sherman Act." The Court recognized that this was "a novel question of antitrust law" and an "issue of first impression in the circuit courts."

The Court noted that while "[p]roduct innovation generally benefits consumers" and courts "are properly very skeptical about claims that competition has been harmed by a dominant firm's product design changes," it is "[w]ell-established" that "product redesign is anticompetitive when it coerces consumers and impedes competition." The Court further noted that, "[c]ertainly, neither product withdrawal nor product improvement alone is anticompetitive," but that "when a monopolist combines product withdrawal with some other conduct, the overall effect of which is to coerce consumers rather than persuade them on the merits and to impede competition, its actions are anticompetitive under the Sherman Act."

The Court concluded that Activas' "hard switch – the combination of introducing Namenda XR into the market and effectively withdrawing Namenda IR – forced Alzheimer's patients who depend on memantine therapy to switch to XR (to which generic IR is not therapeutically equivalent) and would likely impede generic competition by precluding generic substitution through state drug substitution laws."

In so ruling, the Second Circuit addressed and rejected a number of noteworthy arguments advanced by Actavis that attempted to push back on the application of the antitrust laws in these circumstances:

- Generics Can Still Compete. Actavis had argued that IR generics could still successfully compete, even if Namenda IR were withdrawn prior to the expiration of its patent, "by persuading third-party payors and prescription-benefit managers to promote generic IR through the use of formularies, tiered-drug structures, step programs and prior- authorization requirements." The Second Circuit rejected this argument on the ground that such withdrawal foreclosed "the only cost-efficient means of competing available to generic manufacturers," i.e., "competition through state drug substitution laws." The Court effectively refused to burden generic drug makers with the marketing costs that would be necessary to compete via methods other than pharmacist substitution provided for under state law. The Court also stressed that competition would be difficult for generics given the reality that few patients would switch back to generic IR once forced to switch to XR.2

- Superior Nature of New Product Justifies Withdrawal. Actavis had also argued that XR was superior to IR. The Court found that "[w]hether XR is superior to IR is not significant in this case" given the inherently coercive nature of the conduct in forcing patients to switch by withdrawing the older drug from the market.

- Patents Bar Antitrust Liability. Actavis had argued that "their patent rights under Namenda IR and Namenda XR shield them from antitrust liability." The Second Circuit found that, while "there is tension between the antitrust laws' objective of enhancing competition by preventing unlawful monopolies and patent laws' objective of incentivizing innovation by granting legal patent monopolies," patent law only "gives Defendants a temporary monopoly on individual drugs – not a right to use their patents as part of a scheme to interfere with competition beyond the limits of the patent monopoly." The Second Circuit quoted the Supreme Court statement in F.T.C. v. Actavis, Inc., 133 S.Ct. 2223, 2231 (2013) that "patent and antitrust policies are both relevant in determining the scope of the patent monopoly—and consequently antitrust law immunity—that is conferred by a patent," and found that this decision "reaffirmed the conclusions of circuit courts that a patent does not confer upon the patent holder an 'absolute and unfettered right to use its intellectual property as it wishes.'" The Second Circuit further found that "Defendants have essentially tried to use their patent rights on Namenda XR to extend the exclusivity period for all of their memantine-therapy drugs" and stressed that "it is the combination of Defendants' withdrawal of IR and introduction of XR in the context of generic substitution laws that places their conduct beyond the scope of their patent rights for IR or XR individually." In other words, the Second Circuit found it improper for Actavis to leverage its patent on one drug (XR) to monopolize sales in memantine drugs generally.

- Preventing "Free Riding" is Pro-Competitive. Actavis had argued that preventing generics from "free riding" was a legitimate business purpose. The Second Circuit rejected this argument, finding that the type of "free riding" at issue in the case – "generic substitution by pharmacists following the end of Namenda IR's exclusivity period" – "is authorized by law" in light of state substitution statutes and "furthers the goals of the Hatch-Waxman Act by promoting drug competition."

- Launching a New Product is Pro-Competitive. Actavis had argued that launching a new product was pro-competitive. The Second Circuit agreed with that statement as a general proposition, but found that it "provides no procompetitive justification for withdrawing" the older product.3

- Application of Antitrust Laws Will Deter Innovation. Actavis had argued that "antitrust scrutiny of the pharmaceutical industry will meaningfully deter innovation" by, for example, decreasing value drug makers can hope to realize through development of improved versions of drugs. The Second Circuit found the exact opposite under the circumstance of the case, i.e., that "immunizing product hopping from antitrust scrutiny may deter significant innovation by encouraging manufacturers to focus on switching the market to trivial or minor product reformulations rather than investing in the research and development necessary to develop riskier, but medically significant innovations."

Lessons

The Second Circuit's findings and analysis provide a number of helpful guidelines for drug makers seeking to avoid antitrust challenges to efforts to introduce improved versions of a product:

- Hard Switching (Withdrawing the Old Drug) vs. Soft Switching (Leaving the Old Drug on the Market). The Second Circuit draws a bright line between the sort of impermissible "hard switch" Activas had planned – i.e., where the older drug was removed from the market before generic could lawfully compete with it – and a "soft switch" involving the old drug being left on the market, which the Court found would not have violated the antitrust laws under the circumstances. Per the Second Circuit: "As long as Defendants sought to persuade patients and their doctors to switch from Namenda IR to Namenda XR while both were on the market (the soft switch) and with generic IR drugs on the horizon, patients and doctors could evaluate the products and their generics on the merits in furtherance of competitive objectives. By effectively withdrawing Namenda IR prior to generic entry, Defendants forced patients to switch from Namenda IR to XR – the only other memantine drug on the market.'"

- Leaving the Old Product on the Market with Significant Barriers to Access Will Not Ameliorate Antitrust Issues. The Second Circuit decision indicates that imposing significant barriers to purchasing the older product can be viewed as indistinguishable, for antitrust law purposes, from fully withdrawing the product. The withdrawal at issue in Actavis was not a true "hard switch": Actavis had entered into an agreement with a single mail-order-only pharmacy to provide limited access to Namenda IR when a doctor submitted a form to the pharmacy stating that it was "medically necessary" for the patient to take Namenda IR. The Second Circuit, however, was not impressed by this move: citing Activas' internal estimates that "less than 3% of current Namenda IR users would be able to obtain IR" via this method (and noting that the agreement had been made after New York State filed its complaint in the action), the Second Circuit found that this heavily restricted and limited availability did not undermine the conclusion that Activas' "actions effectively withdrew Namenda IR from the market." A question left unresolved is whether any form of partial withdrawal could survive challenge. It is not difficult to understand why a court would treat restrictions that were projected to bar access of the older drug to 97% of current patients as effectively the same as a complete withdrawal. A credible argument could be made for a different result, however, if the effective withdrawal were more moderate.

- Timing of the Product Withdrawal. The Second Circuit decision indicates that the timing of a drug maker's withdrawal of an older drug is critical, finding that removal of "Namenda IR from the market prior to generic IR entry" (i.e., prior to the expiration of Namenda IR's patent protection) was anticompetitive. The decision indicates that it would not violate the antitrust laws to withdraw the older product after generics had a chance to get a foothold. Indeed, the injunction the Second Circuit upheld only barred Actavis from withdrawing Namenda IR "until 30 days after generics enter the market."

-

Intent May Matter. Throughout the decision, the

Second Circuit cites to and quotes from Actavis internal documents

that leave no doubt that its withdrawal of Namenda IR from the

market (and timing of that withdrawal) was motivated by an interest

in maximizing profits by reducing the ability of generic

manufacturers to compete. While the Second Circuit suggests the

outcome would likely have been the same even if this were not the

case, this evidence was a key driver in the district court

decision. The following quotes from Actavis documents cited by the

court are representative:

- "[T]he core of our brand strategy with XR is to convert our existing IR business to Namenda XR as fast as we can and also gain new starts for Namenda XR. We need to transition volume to XR to protect our Namenda revenue from generic penetration in 2015 when we lose IR patent exclusivity."

- "[I]f we do the hard switch and we convert patients and caregivers to once-a-day therapy versus twice a day, it's very difficult for the generics then to reverse-commute back, at least with the existing Rxs. They don't have the sales force. They don't have the capabilities to go do that. It doesn't mean that it can't happen, it just becomes very difficult and is an obstacle that will allow us to, I think, again go into a slow decline versus a complete cliff."

The facts before the Second Circuit represented the extreme: a virtually complete withdrawal of an older product prior to the expiration of its patent protection, a new product that reflected a marginal improvement over the old, patent protection for the newer product that extended 14 years longer than the older product's, a customer base (Alzheimer's patients) especially unlikely to switch back to a generic version of the old product after they have been forced to start taking the new product and unambiguous evidence that the brand manufacturer's intent was to impair the ability of generic manufacturers to compete by switching patients to the new drug before generics could enter the market.4 It remains to be seen how courts will deal with cases involving less stark facts and circumstances, such as a more meaningful improvement to the drug at issue, a less extensive withdrawal of the older product, behavior motivated by genuine procompetitive interests and no documents demonstrating a motive to avoid the patent cliff caused by generic entry.

Footnotes

1.For example, the Second Circuit (like the district court in Abbott) found support for its approach in leading case Berkey Photo, Inc. v. Eastman Kodak Co., 603 F.2d 263 (2d Cir. 1979). Berkey had ruled that Kodak's introduction of a new camera that could only use a type of film patented and made by Kodak did not violate the antitrust laws. However, as the Second Circuit and Abbott both stressed, the ruling in Berkey had been accompanied by the important caveat that "the situation might be completely different if, upon the introduction of the [newer] 110 system, Kodak had ceased producing film in the [older] 126 size, thereby compelling camera purchasers to buy a Kodak 110 camera."

2.A possible basis for distinguishing this part of the analysis in a future case is the Court's description of the unique nature of the disease treated by the drugs at issue, which stresses that patients who use this particular drug are especially unlikely to switch to generic IR once they have been forced to XR: "[T]he nature of Alzheimer's disease makes moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's patients especially vulnerable to changes in routine, and makes doctors and caregivers very reluctant to change a patient's medication if the current treatment is effective. As a result, if Defendants forced patients to switch from twice-daily Namenda IR to once-daily XR, those patients would be very unlikely to switch back to twice-daily generic IR even if generic IR is more cost-effective."

3.The Second Circuit also independently rejected all of Actavis' pro-competitive justifications on the grounds that they were "pretextual," citing the extensive record establishing that Actavis' conduct had been expressly motivated by a desire to prevent generic competition.

4.It is also notable that, because Actavis was a government enforcement action, the plaintiff (the New York Attorney General) benefitted from voluminous pre-litigation discovery that a private plaintiff would not have when attempting to state a claim that can survive a motion to dismiss.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.