Just as the nation's unemployment rate has risen to new levels, so has public pressure on the government to curb employment of undocumented workers. Several states have responded to illegal employment by passing laws that require employers to use a federally created Internet-based program called E-Verify. This electronic verification system allows employers to verify that new hires are authorized to work in the United States by comparing information from employees' Form I-9s with records maintained in federal databases.

While employer participation in E-Verify is voluntary under federal law, the recent United States Supreme Court decision in Chamber of Commerce of the United States v. Whiting has given states the green light to make E-Verify1 participation mandatory for employers. In the 5-3 decision, the Court upheld an Arizona law that, in addition to imposing licensing sanctions on businesses that hire unauthorized workers, requires Arizona businesses to check the work authorization status of new employees through E-Verify. Given this unequivocal endorsement from the High Court, employers should now expect to see a proliferation of state laws requiring mandatory E-Verify participation. Not only will the hiring process change for many employers who hire employees within a state that has passed E-Verify legislation, but multistate employers will be forced to navigate an ever-changing and sometimes contradictory patchwork of state laws.

Development of the E-Verify Program

Sanctions against employers for hiring unauthorized aliens were first created at the federal level in 1986 when Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA).2 IRCA prohibits employers from knowingly or intentionally hiring or continuing to employ an unauthorized alien.3 It also established the I-9 system, which requires employers to complete a Form I-9 for every new hire as a way to demonstrate employer compliance with IRCA.4 Form I-9 requires employees to attest to their eligibility to work, and employers to certify that the documents presented reasonably appear on their face to be genuine and relate to the individual.5 Employers who act in good faith compliance with the I-9 system are entitled to an affirmative defense to federal employer sanctions.6

In 1996, Congress passed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), which created three pilot programs to improve the efficiency and accuracy of the I-9 verification process.7 Of those three programs, E-Verify, formerly called the Basic Pilot Program, is the only program still in existence. A free Internet-based program, E-Verify is administered by the Secretary of Homeland Security.8 It allows employers to compare employees' Form I-9 information with records in the Social Security Administration database and the Department of Homeland Security's immigration databases. E-Verify does not replace the I-9 system, and employers who elect to participate in E-Verify must still complete Form I-9 for every new employee.9 While employers who in good faith comply with the I-9 system are entitled to an affirmative defense to sanctions, those who use E-Verify are entitled to a rebuttable presumption that they did not knowingly hire an unauthorized employee.10

With limited exceptions for certain federal government entities and IRCA violators, participation in E-Verify is voluntary under federal law. "Except as specifically provided in subsection (e), the [Secretary of Homeland Security] may not require any person or other entity to participate in a pilot program."11 In addition, the Federal Acquisition Regulation12 requires many federal contractors to use E-Verify to verify the employment eligibility of certain new and current employees.

While federal law still makes E-Verify voluntary for most employers, the Supreme Court decision in Chamber of Commerce of the United States v. Whiting now authorizes state governments to mandate participation by all employers.

Supreme Court Decision in Chamber of Commerce of the United States v. Whiting

The issue before the Whiting Court was whether federal immigration laws preempted the controversial Legal Arizona Workers Act (LAWA).13 Enacted in 2007, LAWA authorizes the Arizona Attorney General and county attorneys to bring legal actions against employers who knowingly or intentionally employ unauthorized aliens. Under LAWA, the Arizona superior court may suspend or revoke an employer's business license after repeated violations of the statute. LAWA also mandates that all employers within Arizona must use E-Verify to verify the immigration status of new employees.

Within a month of LAWA's enactment, the Chamber of Commerce of the United States, along with several businesses and civil rights groups, filed a lawsuit against Arizona state officials to challenge the constitutionality of LAWA.14 The Chamber of Commerce argued that LAWA should be invalidated because IRCA expressly and impliedly preempts LAWA. Both the district court and appellate court disagreed. Affirming the lower court, the Ninth Circuit held that LAWA was a "licensing or similar law" exempted from IRCA's preemption clause and that Arizona's licensing sanctions and E-Verify requirement escaped implied preemption because they were consistent with congressional intent.15

On May 26, 2011, in Chamber of Commerce of the United States v. Whiting, the Supreme Court affirmed the Ninth Circuit's decision. The Court held that: (1) Arizona's licensing law was not expressly preempted by federal law; (2) Arizona's licensing law was not impliedly preempted by federal law; and (3) Arizona's requirement that employers use E-Verify was not impliedly preempted.

First, the Court held that LAWA falls within the authority Congress left to the states and therefore is not expressly preempted. The Court reasoned that although states may not impose civil or criminal sanctions on businesses that employ unauthorized aliens, they may impose sanctions "through licensing and similar laws." These sanctions may include revocation of a business's state-issued authorization to conduct business within the state. "Licenses" subject to revocation under Arizona's law include "any agency permit, certificate, approval, registration, charter or similar form of authorization that is required by law and that is issued . . . for the purposes of operating in the business in this state," including "articles of incorporation, certificates of partnership, foreign corporation registrations, and transaction privilege licenses."

Second, the Court held that LAWA's unauthorized worker provision is not impliedly preempted because it implements the sanctions Congress expressly allowed the states to pursue through licensing laws. When Congress reserved this authority for the states, the Court reasoned, it must have intended for the states to use appropriate tools to exercise the authority. Furthermore, LAWA follows all of IRCA's material provisions, including using the same definition of "unauthorized alien." LAWA does not disrupt the careful balance Congress struck in enacting IRCA because federal and state laws protect against employment discrimination, LAWA only covers knowing and intentional violations, and LAWA provides a safe harbor for employers who use E-Verify as required by the law.

Third, the Court concluded that LAWA's requirement that employers use E-Verify is not impliedly preempted because it does not conflict with the federal requirements.

The fact that the federal government may only require its use in limited circumstances says nothing about when the states may do so. The consequences of an employer's failure to use E-Verify are the same under the Arizona and federal law — the employer loses the benefit of the rebuttable presumption of compliance with the law. Furthermore, LAWA does not obstruct the goal of IIRIRA, as Congress has expanded and encouraged the use of E-Verify and directed that it be made available in all 50 states.

State E-Verify Laws

Even before the Whiting decision, several states made E-Verify participation mandatory for employers located within those states as well as those who contract to provide services to those states. Of the 17 states with E-Verify mandates in place today, the following eight states require employers, both public and private, to participate in E-Verify depending on the number of employees: Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Utah. While the remaining states limit mandatory E-Verify participation to public employers or contractors, it may only be a matter of time before these and new laws will extend to private employers as well.

As new laws surface, employers may find themselves forced to comply with state E-Verify laws that facially contradict federal requirements or the requirements of the laws of other states. For example, on January 4, 2011, Florida Governor Rick Scott signed Executive Order 11-04, mandating that all Florida state agencies, as a condition of awarding a state contract, use the E-Verify system to verify the employment eligibility of "(a) all persons employed during the contract term by the contractor to perform employment duties within Florida; and (b) all persons [including subcontractors] assigned by the contractor to perform work pursuant to the contract with the state agency." Based on a plain reading of the language, the Executive Order required the use of E-Verify to check the employment status of current employees in violation of federal rules prohibiting the use of E-Verify for current employees. Indeed, under a "Memorandum of Understanding" that employers must sign to enroll in E-Verify, employers who use E-Verify for current employees risk being terminated from the program altogether. Luckily, Florida evidently realized the conundrum it created for employers and on May 27, 2011, Governor Scott signed a new Executive Order superseding his original order which clarifies E-Verify is to be used only for new hires. The fix may not always be so simple. If placed in an E-Verify Catch 22, employers should first seek clarification from the state authority responsible for enforcing the E-Verify requirement and consult legal counsel.

States with Mandatory E-Verify Laws

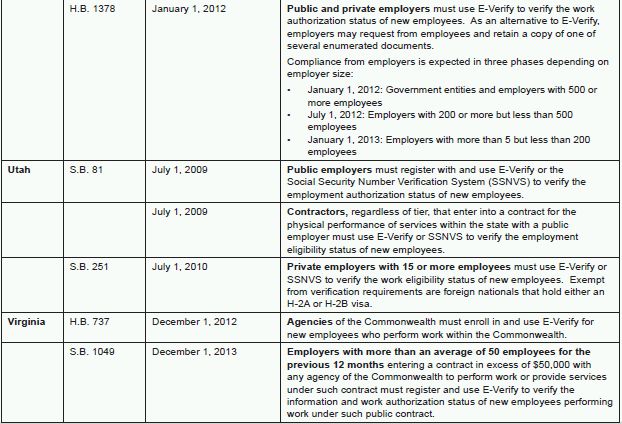

At the end of this article Table 1 summarizes E-Verify legislation that has been passed in several states; it does not include proposed legislation. Its purpose is to provide employers with a snapshot of today's E-Verify landscape, but note that it is not a comprehensive summary of individual state laws. Moreover, state E-Verify legislation is a dynamic area of law, and increased activity in the wake of the Whiting decision is a virtual certainty. Accordingly, employers should refer to state legislature websites for the most up-to-date information on state E-Verify requirements to ensure compliance. In case of doubt, employers should consult counsel for guidance.

Life After E-Verify: What Should Employers Do Now?

With momentum building for state E-Verify mandates, employers should expect to see stricter enforcement nationwide. In several states, failure to use E-Verify could result in suspension of business licenses, termination of contracts, civil fines, or debarment from contracting with the state altogether. To avoid these harsh sanctions, employers should thoroughly review each state's E-Verify requirements, and take proper measures to ensure compliance.

To start, employers new to E-Verify (or even those who have been participating in the program for some time) should consider adopting some of the following useful hiring practices:

- For multistate employers obligated to use E-Verify in one state, consider adopting E-Verify companywide to avoid conflicting standards within the company (not to mention confusion for Human Resources and employees).

- Do not use E-Verify on current employees. Unless the employer has been awarded a federal contract on or after September 8, 2009, this is prohibited by federal guidelines.

- Require uniform verification of new employees. Even if an employer is required to use E-Verify for certain employees only, selective use of E-Verify may be perceived as discriminatory.

- Never use E-Verify on a job applicant prior to hiring. If the candidate is not hired, the candidate may later bring charges of discrimination against the employer.

- If available in the employer's state, inform all job applicants about the E-Verify Self Check service. Self Check is available in Idaho, Arizona, Colorado, Mississippi, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. Because E-Verify is not yet bug-free, prospective employees could save their employers precious time and money by resolving erroneous results before starting employment.

Again this is a changing area of the law that is highly politicized and fraught with minefields. Employers should proceed carefully in this area and seek guidance from experienced counsel when necessary.

Table 1: State E-Verify Laws

Footnotes

1. Chamber of Commerce of United States. v. Whiting, 563 U.S. ___ (2011) (09-115).

2. IRCA, Pub. L. 99-603, 100 Stat. 3359 (1986).

3. 8 U.S.C. § 1324a(a)(1).

4. Id. at 1324a(b).

5. U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Servs, Handbook for Employers: Instructions for Completing Form I-9 (Employment Eligibility Verification Form) 11, http://www.uscis.gov/files/form/m-274.pdf.

6. Id. § 1324a(b)(6).

7. IIRIRA, Pub. L. 104-208, §§ 401-405, 110 Stat. 3009, 3009-655 to 3009-666 (1996).

8. Id. at 403.

9. Id. at 403(a)(1); see U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Servs., E-Verify User Manual for Employers 13, http://www.uscis.gov/USCIS/E-Verify/Customer%20Support/E-Verify%20User%20Manual%20for%20Employers%20R3%200-%20Final.pdf.

10. IIRIRA § 402(b)(1).

11. Id. at 402; see Chamber of Commerce v. Edmondson, 594 F.3d 742, 768 (10th Cir. 2010) (internal citations omitted).

12. See Federal Acquisition Regulation, 48 C.F.R. pts. 1-53 (2010).

13. Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. §§ 23-211, 212, 212.01.

14. Ariz. Contractors Ass'n v. Candelaria, 534 F.Supp.2d 1036 (D. Ariz. 2008).

15. Chicanos Por La Causa, Inc. v. Napolitano, 544 F.3d 976 (9th Cir. 2008).

Because of the generality of this update, the information provided herein may not be applicable in all situations and should not be acted upon without specific legal advice based on particular situations.

© Morrison & Foerster LLP. All rights reserved